Betjeman’s Best British Churches

Who has heard a muffled peal and remained unmoved? Leather bags are tied to one side of the clapper and the bells ring alternately loud and soft, the soft being an echo, as though in the next world, of the music we hear on earth.

I make no apology for writing so much about church bells. They ring through our literature, as they do over our meadows and roofs and few remaining elms. Some may hate them for their melancholy, but they dislike them chiefly, I think, because they are reminders of Eternity. In an age of faith they were messengers of consolation.

The bells are rung down, the ting-tang will ring for five minutes, and now is the time to go into Church.

The Interior Today

As we sit in a back pew of the nave with the rest of the congregation – the front pews are reserved for those who never come to church – most objects which catch the eye are Victorian. What we see of the present age is cheap and sparse. The thick wires clamped on to the old outside wall, which make the church look as though the vicar had put it on the telephone, are an indication without that electric light has lately been introduced. The position of the lights destroys the effect of the old mouldings on arches and columns. It is a light too harsh and bright for an old building, and the few remaining delicate textures on stone and walls are destroyed by the dazzling floodlights fixed in reflectors from the roof, and a couple of spotlights behind the chancel arch which throw their full radiance on the brass altar vases and on the vicar when he marches up to give the blessing. At sermon time, in a winter evensong, the lights are switched off, and the strip reading-lamp on the pulpit throws up the vicar’s chin and eyebrows so that he looks like Grock. A further disfigurement introduced by electrical engineers is a collection of meters, pipes and fuses on one of the walls.1 If a church must be lit with electricity – which is in any case preferable to gas, which streaks the walls – the advice of Sir Ninian Comper might well be taken. This is to have as many bulbs as possible of as low power as possible, so that they do not dazzle the eye when they hang from the roof and walls. Candles are the perfect lighting for an old church, and oil light is also effective. The mystery of an old church, however small the building, is preserved by irregularly placed clusters of low-powered bulbs which light service books but leave the roof in comparative darkness. The chancel should not be strongly lit, for this makes the church look small, and all too rarely are chancel and altar worthy of a brilliant light. I have hardly ever seen an electrically lit church where this method has been employed, and we may assume that the one in which we are sitting is either floodlit or strung with blinding pendants whose bulbs are covered by ‘temporary’ shades reminiscent of a Government office.

1 I have even seen electric heaters hung at intervals along the gallery of an 18th-century church and half-way up the columns of a medieval nave.

Other modern adornments are best seen in daylight, and it is in daylight that we will imagine the rest of the church. The ‘children’s corner’ in front of the side altar, with its pale reproductions of water-colours by Margaret W. Tarrant, the powder-blue hangings and unstained oak kneelers, the side altar itself, too small in relation to the aisle window above it, the pale stained-glass figure of St George with plenty of clear glass round it (Diocesan Advisory Committees do not like exclusion of daylight) or the anaemic stained-glass soldier in khaki – these are likely to be the only recent additions to the church, excepting a few mural tablets in oak or Hopton Wood stone, much too small in comparison with the 18th-century ones, dotted about on the walls and giving them the appearance of a stamp album; these, thank goodness, are the only damage our age will have felt empowered to do.

The Interior in 1860

In those richer days when a British passport was respected throughout the world, when ‘carriage folk’ existed and there was a smell of straw and stable in town streets and bobbing tenants at lodge gates in the country, when it was unusual to boast of disbelief in God and when ‘Chapel’ was connected with ‘trade’ and ‘Church’ with ‘gentry’, when there were many people in villages who had never seen a train nor left their parish, when old farm-workers still wore smocks, when town slums were newer and even more horrible, when people had orchids in their conservatories and geraniums and lobelias in the trim beds beside their gravel walks, when stained glass was brownish-green and when things that shone were considered beautiful, whether they were pink granite, brass, pitchpine, mahogany or encaustic tiles, when the rector was second only to the squire, when doctors were ‘apothecaries’ and lawyers ‘attorneys’, when Parliament was a club, when shops competed for custom, when the servants went to church in the evening, when there were family prayers and basement kitchens – in those days God seemed to have created the universe and to have sent His Son to redeem the world, and there was a church parade to worship Him on those shining Sunday mornings we read of in Charlotte M. Yonge’s novels and feel in Trollope and see in the drawings in Punch. Then it was that the money pouring in from our empire was spent in restoring old churches and in building bold and handsome new ones in crowded areas and exclusive suburbs, in seaside towns and dockland settlements. They were built by the rich and given to the poor: ‘All Seats in this Church are Free.’ Let us now see this church we have been describing as it was in the late 1860s, shining after its restoration.

Changed indeed it is, for even the aisles are crowded and the prevailing colours of clothes are black, dark blue and purple. The gentlemen are in frock coats and lean forward into their top hats for a moment’s prayer, while the lesser men are in black broad-cloth and sit with folded arms awaiting the rector. He comes in after his curate and they sit at desks facing each other on either side of the chancel steps. Both wear surplices: the Rector’s is long and flowing and he has a black scarf round his shoulders: so has the curate, but his surplice is shorter and he wears a cassock underneath, for, if the truth be told, the curate is ‘higher’ than the rector and would have no objection to wearing a coloured stole and seeing a couple of candles lit on the altar for Holy Communion. But this would cause grave scandal to the parishioners, who fear idolatry. Those who sit in the pews in the aisles where the seats face inward, never think of turning eastwards for the Creed. Hymns Ancient and Modern has been introduced. The book is ritualistic, but several excellent men have composed and written for it, like Sir Frederick Ouseley and Sir Henry Baker, and Bishops and Deans. The surpliced choir precede the clergy and march out of the new vestry built on the north-east corner of the church. Some of the older men, feeling a little ridiculous in surplices, look wistfully towards the west end where the gallery used to be and where they sang as youths to serpent, fiddle and bass recorder in the old-fashioned choir, before the pipe organ was introduced up there in the chancel. The altar has been raised on a series of steps, the shining new tiles becoming more elaborate and brilliant the nearer they approach the altar. The altar frontal has been embroidered by ladies in the parish, a pattern of lilies on a red background. There is still an alms dish on the altar, and behind it a cross has been set in stone on the east wall. In ten years’ time brass vases of flowers, a cross and candlesticks will be on a ‘gradine’ or shelf above the altar. The east window is new, tracery and all. The glass is green and red, shewing the Ascension – the Crucifixion is a little ritualistic – and has been done by a London firm. And a smart London architect designed all these choir stalls in oak and these pews of pitch-pine in the nave and aisles. At his orders the new chancel roof was constructed, the plaster was taken off the walls of the church, and the stone floors were taken up and transformed into a shining stretch of red and black tiles. He also had that pale pink and yellow glass put in all the unstained windows so that a religious light was cast. The brass gas brackets arc by Skidmore of Coventry. Some antiquarian remains are carefully preserved. A Norman capital from the old aisle which was pulled down, a pillar piscina, a half of a cusped arch which might have been – no one knows quite what it might have been, but it is obviously ancient. Unfortunately it was not possible to remove the pagan classical memorials of the last century owing to trouble about faculties and fear of offending the descendants of the families commemorated. The church is as good as new, and all the medieval style of the middle-pointed period – the best period because it is in the middle and not ‘crude’ like Norman and Early English, or ‘debased’ like Perpendicular and Tudor. Nearly everyone can see the altar. The Jacobean pulpit has survived, lowered and re-erected on a stone base. Marble pulpits are rather expensive, and Jacobean is not wholly unfashionable so far as woodwork is concerned. The prevailing colours of the church are brown and green, with faint tinges of pink and yellow.

Not everyone approved of these ‘alterations’ in which the old churches of England were almost entirely rebuilt. I quote from Alfred Rimmer’s Pleasant Spots Around Oxford (c. 1865), on the taking down of the body of Woodstock’s classical church.

‘Well, during the month of July I saw this church at Woodstock, but unhappily, left making sketches of it till a future visit. An ominous begging-box, with a lock, stood out in the street asking for funds for the “restoration”. One would have thought it almost a burlesque, for it wanted no restoration at all, and would have lasted for ever so many centuries; but the box was put up by those “who said in their hearts, Let us make havoc of it altogether”. Within a few weeks of the time this interesting monument was perfect, no one beam was left; and now, as I write, it is a “heap of stones”. Through the debris I could just distinguish a fine old Norman doorway that had survived ever so many scenes notable in history, but it was nearly covered up with ruins; and supposing it does escape the general melee, and has the luck to be inserted in a new church, with open benches and modern adornments, it will have lost every claim to interest and be scraped down by unloving hands to appear like a new doorway. Happily, though rather late in the day, an end is approaching to these vandalisms.’

The Church in Georgian Times

See now the outside of our church about eighty years before, in, let us say, 1805, when the two-folio volumes on the county were produced by a learned antiquarian, with aquatint engravings of the churches, careful copper-plates of fonts and supposedly Roman pieces of stone, and laborious copyings of entries in parish rolls. How different from the polished, furbished fane we have just left is this humble, almost cottage-like place of worship. Oak posts and rails enclose the churchyard in which a horse, maybe the Reverend Dr Syntax’s mare Grizzel, is grazing. The stones are humble and few, and lean this way and that on the south side. They are painted black and grey and the lettering on some is picked out in gold. Two altar tombs, one with a sculptured urn above it, are enclosed in sturdy iron rails such as one sees above the basements of Georgian terrace houses. Beyond the church below a thunderous sky we see the elm and oak landscape of an England comparatively unenclosed. Thatched cottages and stone-tiled farms are collected round the church, and beyond them on the boundaries of the parish the land is still open and park-like, while an unfenced road winds on with its freight of huge bonnetted wagons. Later in the 19th century this land was parcelled into distant farms with significant names like ‘Egypt’, ‘California’, ‘Starveall’, which stud the ordnance maps. Windmills mark the hill-tops and water-mills the stream. Our church to which this agricultural world would come, save those who in spite of Test Acts and suspicion of treachery meet in their Dissenting conventicles, is a patched, uneven-looking place.

Sympathetic descriptive accounts of unrestored churches are rarely found in late Georgian or early Victorian prose or verse. Most of the writers on churches are antiquarians who see nothing but ancient stones, or whose zeal for ‘restoration’ colours their writing. Thus for instance Mr John Noake describes White Ladies’ Aston in Worcestershire in 1851 (The Rambler in Worcestershire, London, Longman and Co., 1851). ‘The church is Norman, with a wooden broach spire; the windows, with two or three square-headed exceptions, are Norman, including that at the east end, which is somewhat rare. The west end is disgraced by the insertion of small square windows and wooden frames, which, containing a great quantity of broken glass, and a stove-pipe issuing therefrom impart to the sacred building the idea of a low-class lodging house.’ And writing at about the same time, though not publishing until 1888, the entertaining Church-Goer of Bristol thus describes the Somerset church of Brean:

‘On the other side of the way stood the church – little and old, and unpicturesquely freshened up with whitewash and yellow ochre; the former on the walls and the latter on the worn stone mullions of the small Gothic windows. The stunted slate-topped tower was white-limed, too – all but a little slate slab on the western side, which bore the inscription:

JOHN GHENKIN

Churchwarden

1729

Anything owing less to taste and trouble than the little structure you would not imagine. Though rude, however, and old, and kept together as it was by repeated whitewashings, which mercifully filled up flaws and cracks, it was not disproportioned or unmemorable in aspect, and might with a trifling outlay be made to look as though someone cared for it.’

Such a church with tracery ochred on the outside may be seen in the background of Millais’ painting The Blind Girl. It is, I believe, Winchelsea before restoration. Many writers, beside Rimmer, regret the restoration of old churches by London architects in the last century. The despised Reverend J. L. Petit, writing in 1841 in those two volumes called Remarks on Church Architecture, illustrated with curious anastatic sketches, was upbraided by critics for writing too much by aesthetic and not enough by antiquarian standards.

He naturally devoted a whole chapter to regretting restoration. But neither he nor many poets who preceded him bothered to describe the outside appearance of unrestored village churches, and seldom did they relate the buildings to their settings. ‘Venerable’, ‘ivy-mantled’, ‘picturesque’ are considered precise enough words for the old village church of Georgian times, with ‘neat’, ‘elegant’ or ‘decent’ for any recent additions. It is left for the Reverend George Crabbe, that accurate and beautiful observer, to recall the texture of weathered stone in The Borough, Letter II (1810):

But ’ere you enter, yon bold tower survey

Tall and entire, and venerably grey,

For time has soften’d what was harsh when new,

And now the stains are all of sober hue;

and to admonish the painters:

And would’st thou, artist! with thy tints and brush

Form shades like these? Pretender, where thy brush?

In three short hours shall thy presuming hand

Th’ effect of three slow centuries command?

Thou may’st thy various greens and greys contrive

They are not lichens nor light aught alive.

But yet proceed and when thy tints are lost,

Fled in the shower, or crumbled in the frost

When all thy work is done away as clean

As if thou never spread’st thy grey and green,

Then may’st thou see how Nature’s work is done,

How slowly true she lays her colours on . . .

With the precision of the botanist, Crabbe describes the process of decay which is part of the beauty of the outside of an unrestored church:

Seeds, to our eye invisible, will find

On the rude rock the bed that fits their kind:

There, in the rugged soil, they safely dwell,

Till showers and snows the subtle atoms swell,

And spread th’ enduring foliage; then, we trace

The freckled flower upon the flinty base;

These all increase, till in unnoticed years

The stony tower as grey with age appears;

With coats of vegetation thinly spread,

Coat above coat, the living on the dead:

These then dissolve to dust, and make a way

For bolder foliage, nurs’d by their decay:

The long-enduring ferns in time will all

Die and despose their dust upon the wall

Where the wing’d seed may rest, till many a flower

Show Flora’s triumph o’er the falling tower.

WILLEN: ST MARY – a Classical church of the 1670s by Robert Hooke, it points the way to the Georgian interiors of the following century

© Michael Ellis

Yet the artists whom Crabbe admonishes have left us better records than there are in literature of our churches before the Victorians restored them. The engravings of Hogarth, the water-colours and etchings of John Sell Cotman and of Thomas Rowlandson, the careful and less inspired records of John Buckler, re-create these places for us. They were drawn with affection for the building as it was and not ‘as it ought to be’; they bring out the beauty of what Mr Piper has called ‘pleasing decay’; they also shew the many churches which were considered ‘neat and elegant’.

It is still possible to find an unrestored church. Almost every county has one or two.

The Georgian Church Inside

There is a whole amusing literature of satire on church interiors. As early as 1825, an unknown wit and champion of Gothic published a book of coloured aquatints with accompanying satirical text to each plate, entitled Hints to Some Churchwardens. And as we are about to enter the church, let me quote this writer’s description of a Georgian pulpit: ‘How to substitute a new, grand, and commodious pulpit in place of an ancient, mean, and inconvenient one. Raze the old Pulpit and build one on small wooden Corinthian pillars, with a handsome balustrade or flight of steps like a staircase, supported also by wooden pillars of the Corinthian order; let the dimensions of the Pulpit be at least double that of the old one, and covered with crimson velvet, and a deep gold fringe, with a good-sized cushion, with large gold tassels, gilt branches on each side, over which imposing structure let a large sounding-board be suspended by a sky-blue chain with a gilt rose at the top, and small gilt lamps on the side, with a flame painted, issuing from them, such Pulpits as these must please all parties; and as the energy and eloquence of the preacher must be the chief attraction from the ancient Pulpit, in the modern one, such labour is not required, as a moderate congregation will be satisfied with a few short sentences pronounced on each side of the gilt branches, and sometimes from the front of the cushion, when the sense of vision is so amply cared for in the construction of so splendid and appropriate a place from which to teach the duties of Christianity.’

And certainly the pulpit and the high pews crowd the church. The nave is a forest of woodwork. The pews have doors to them. The panelling inside the pews is lined with baize, blue in one pew, red in another, green in another, and the baize is attached to the wood by brass studs such as one may see on the velvet-covered coffins in family vaults. Some very big pews will have fire-places. When one sits down, only the pulpit is visible from the pew, and the tops of the arches of the nave whose stonework will be washed with ochre, while the walls will be white or pale pink, green or blue. A satire on this sort of seating was published by John Noake in 1851 in his book already quoted:

O my own darling pue, which might serve for a bed,

With its cushions so soft and its curtains of red;

Of my half waking visions that pue is the theme,

And when sleep seals my eyes, of my pue still I dream.

Foul fall the despoiler, whose ruthless award

Has condemned me to squat, like the poor, on a board,

To be crowded and shov’d, as I sit at my prayers,

As though my devotions could mingle with theirs.

I have no vulgar pride, oh dear me, not I,

But still I must say I could never see why

We give them room to sit, to stand or to kneel,

As if they, like ourselves, were expected to feel;

’Tis a part, I’m afraid, of a deeply laid plan

To bring back the abuses of Rome if they can.

And when SHE is triumphant, you’ll bitterly rue

That you gave up that Protestant bulwark – your pew.

The clear glass windows, of uneven crown glass with bottle-glass here and there in the upper lights, will shew the churchyard yews and elms and the flying clouds outside. Shafts of sunlight will fall on hatchments, those triangular-framed canvases hung on the aisle walls and bearing the Arms of noble families of the place. Over the chancel arch hang the Royal Arms, painted by some talented inn-sign artist, with a lively lion and unicorn supporting the shield in which we may see quartered the white horse of Hanover. The roofs of the church will be ceiled within for warmth, and our boxed-in pew will save us from draught. Look behind you; blocking the tower arch you will see a wooden gallery in which the choir is tuning its instruments, fiddle, base viol, serpent. And on your left in the north aisle there is a gallery crowded under the roof. On the tiers of wooden benches here sit the charity children in their blue uniforms, within reach of the parish beadle who, in the corner of the west gallery, can admonish them with his painted stave.

The altar is out of sight. This is because the old screen survives across the chancel arch and its doors are locked. If you can look through its carved woodwork, you will see that the chancel is bare except for the memorial floor slabs and brasses of previous incumbents, and the elaborate marble monument upon the wall, by a noted London sculptor, in memory of some lay-rector of the 18th century. Probably this is the only real ‘work of art’ judged by European standards in the church. The work of 18th-century sculptors has turned many of our old churches into sculpture galleries of great interest, though too often the Victorians huddled the sculptures away in the tower or blocked them up with organs. No choir stalls are in the chancel, no extra rich flooring. The Lord’s Table or altar is against the east wall and enclosed on three sides by finely-turned rails such as one sees as stair balusters in a country house. The Table itself is completely covered with a carpet of plum-covered velvet, embroidered on its western face with IHS in golden rays. Only on those rare occasions, once a quarter and at Easter and Christmas and Whit Sunday when there is to be a Communion service, is the Table decked. Then indeed there will be a fair linen cloth over the velvet, and upon the cloth a chalice, paten and two flagons all of silver, and perhaps two lights in silver candlesticks. On Sacrament Sundays those who are to partake of Communion will leave their box-pews either at the Offertory Sentence (when in modern Holy Communion services the collection is taken), or at the words ‘Ye that do truly and earnestly repent you of your sins, and are in love and charity with your neighbours’, and they will be admitted through the screen doors to the chancel. They will have been preceded by the incumbent. Thereafter the communicants will remain kneeling until the end of the service, as many as can around the Communion rails, the rest in the western side of the chancel.

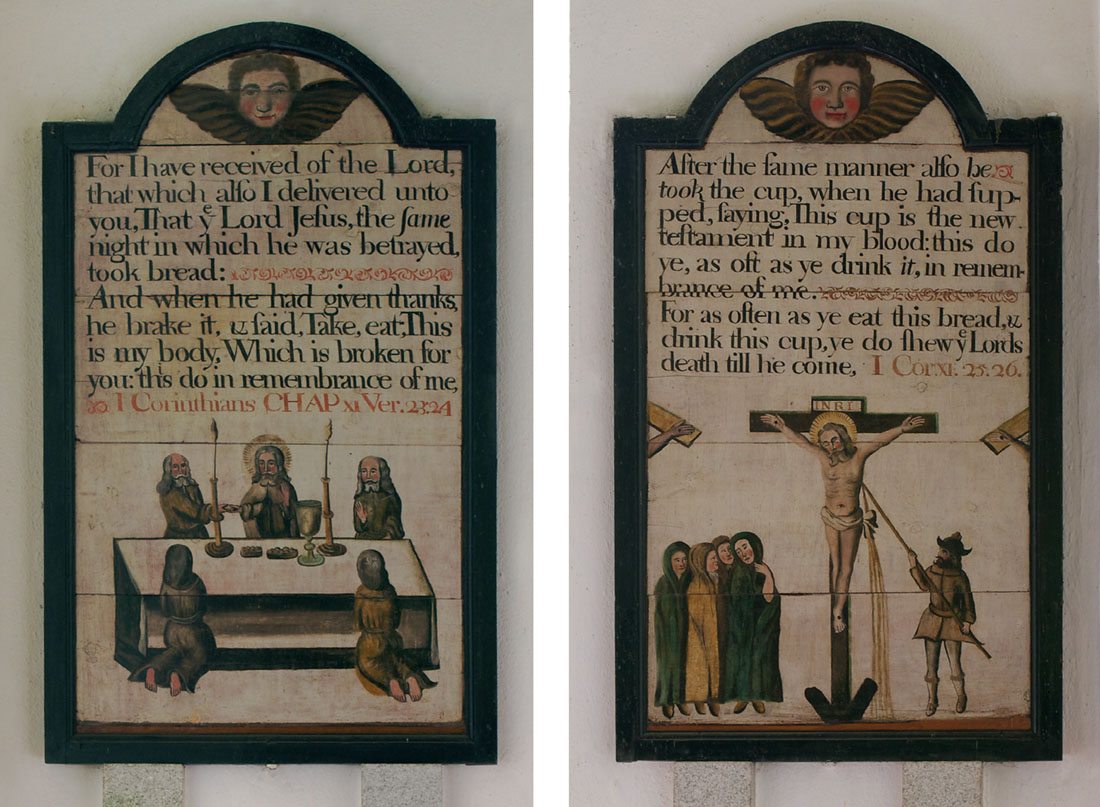

ALTARNUN: ST NONNA – painted panels with biblical texts and images became popular from the 17th century; these from Cornwall hang either side of the high altar