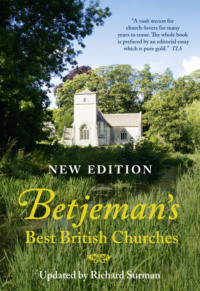

Betjeman’s Best British Churches

© Michael Ellis

Another reason for the erection of new churches in the 18th century was the inadequacy of medieval buildings. They could sometimes hold galleries erected in the aisles and at the west end, but no more. Old prints shew us town churches which have almost the appearance of an opera house, galleries projecting beyond galleries, with the charity children away up in the top lighted by dormers in the roof, pews all over the aisles and in the chancel, and only here and there a pointed arch or a bit of window tracery to shew that this was once a gothic medieval church. Walls began to bulge, stone decayed, structures were unsound and ill-behaved children could not be seen by the beadle and clerk. The only thing to do was to pull down the building. A surviving interior of this sort is the parish church of Whitby. To go into it is like entering the hold of a ship. There are box-pews shoulder high in all directions, galleries, private pews, and even a pew over the chancel screen. Picturesque and beautiful as it is, with the different colours of baize lining the pews, and the splendid joinery of varying dates, such an uneven effect cannot have pleased the 18th-century man of taste. Therefore when they became overloaded with pews, these old churches were taken down and new ones in Classic or Strawberry Hill Gothick style were erected on the sites.

In the country there can have been little need to rebuild the old church on the grounds of lack of accommodation. Here rebuilding was done at the dictates of taste. A landlord might find the church too near his house, or sited wrongly for a landscape improvement he was contemplating in the park, or he might simply dislike the old church on aesthetic grounds as a higgledy-piggledy, barbarous building. Most counties in England have more than one 18th-century church, now a sad relic in a park devastated by timber merchants, still crowning some rise or looking like a bit of Italy or ancient Greece in the pastoral English landscape.

Eighteenth-century churches are beautiful primarily because of their proportions. But they were not without colour. Painted hatchments adorned the walls, gilded tables of the Commandments were over the altar, with Moses and Aaron on either side, the Royal Arms on painted wood or coloured plaster was above the chancel opening, coloured baize lines in the pews, rich velvets of all colours were hanging from the high pulpit and the desks below it, an embroidered velvet covering decked the altar in wide folds, gilded candles and alms dish stood on the altar. The art of stained glass was not dead in the 18th century as is often supposed. East windows were frequently coloured, with pieces of golden-yellow 16th-century foreign glass brought back from a Grand Tour, and gold, blue and dark green glass, partly pot-metal and partly coloured transparency, such as went on being made in York until late in the century. Another popular kind of window was the coloured transparency – a transparent drawing enamelled on to glass, like the Reynolds’ window in New College, Oxford, by such artists as Eginton of Birmingham, Peckitt of York, James Pearson and Jervais.

After 1760 country churches were often rebuilt in the Gothick taste. Pointed windows, pinnacled towers and battlemented walls were considered ecclesiastical and picturesque. They went with sham ruins and amateur antiquarianism, then coming into fashion. The details of these Gothick churches were not correct according to ancient examples. Nor do I think they were intended to be. Their designers strove after a picturesque effect, not antiquarian copying. The interiors were embellished with Chippendale Gothick woodwork and plaster-work. Again nothing was ‘correct’. Who had ever heard of a medieval box-pew or an ancient ceiling that was plaster moulded? The Gothick taste was but plaster deep, concerned with a decorative effect and not with structure. The supreme example of this sort of church is Shobdon, Herefordshire (1753).

Amid all this concern with taste, industrialism comes upon us. It was all very well for the squire to fritter away his time with matters of taste in his country park, all very well for Boulton and Watt to try to harness taste to their iron-works at Soho, as Darby before them had tried at Ironbridge; the mills of the midlands and the north were rising. Pale mechanics, slave-driven children and pregnant women were working in the new factories. The more intelligent villagers were leaving for the towns where there was more money to be made. From that time until the present day, the country has been steadily drained of its best people. Living in hovels, working in a rattling twilight of machines, the people multiplied. Ebenezer Elliott the Corn Law Rhymer (1781–1849) was their poet:

The day was fair, the cannon roar’d,

Cold blew the bracing north,

And Preston’s mills, by thousands, pour’d

Their little captives forth . . .

But from their lips the rose had fled,

Like ‘death-in-life’ they smiled;

And still, as each pass’d by, I said,

Alas! is that a child? . . .

Thousands and thousands – all so white! –

With eyes so glazed and dull!

O God! it was indeed a sight

Too sadly beautiful!

A Christian himself, Ebenezer called out above

the roar of the young industrial age:

When wilt thou save the People?

O God of mercy, when?

The people, Lord, the people,

Not thrones and crowns, but men!

Flowers of thy heart, O God, are they;

Let them not pass, like weeks, away, –

Their heritage a sunless day.

God save the people!

The composition of this poem was a little later than the Million Act of 1818, by which Parliament voted one million pounds towards the building of churches in new districts. The sentiments of the promoters of the Bill cannot have been so unlike those of Elliott. Less charitable hearts, no doubt, terrified by the atheism consequent on the French Revolution and apprehensive of losses to landed proprietors, regarded the Million Act as a thank-offering to God for defending them from French free-thinking and continental economics. Others saw in these churches bulwarks against the rising tide of Dissent. Nearly three hundred new churches were built in industrial areas between 1819 and 1830. The Lords Commissioner of the Treasury who administered the fund required them to be built in the most economical mode, ‘with a view to accommodating the greatest number of persons at the smallest expense within the compass of an ordinary voice, one half of the number to be free seats for the poor’. A limit of £20,000 was fixed for 2,000 persons. Many of these ‘Commissioners’ or ‘Waterloo’ churches, as they are now called, were built for £10,000. The most famous church of this date is St Pancras in London, which cost over £70,000. But the money was found by private subscription and a levy on the rates. For other and cheaper churches in what were then poorer districts the Commissioners contributed towards the cost.

The Commissioners themselves approved all designs. When one reads some of the conditions they laid down, it is surprising to think that almost every famous architect in the country designed churches for them – Soane, Nash, Barry, Smirke, the Inwoods, the Hardwicks, Rickman (a Quaker and the inventor of those useful terms for Gothic architecture, ‘Early English’, ‘Decorated’ and ‘Perpendicular’), Cockerell & Basevi and Dobson, to name a few. ‘The site must be central, dry and sufficiently distant from factories and noisy thoroughfares; a paved area is to be made round the church. If vaulted underneath, the crypt is to be made available for the reception of coals or the parish fire engine. Every care must be taken to render chimneys safe from fire; they might be concealed in pinnacles. The windows ought not to resemble modern sashes; but whether Grecian or Gothic, should be in small panes and not costly. The most favourable position for the minister is near an end wall or in a semicircular recess under a half dome. The pulpit should not intercept a view of the altar, but all seats should be placed so as to face the preacher. We should recommend pillars of cast iron for supporting the gallery of a chapel, but in large churches they might want grandeur. Ornament should be neat and simple, yet variable in character.’

In short, what was wanted was a cheap auditorium, and, whether Grecian or Gothic, the solution seems always to have been the same. The architects provided a large rectangle with an altar at the end in a very shallow chancel, a high pulpit on one side of the altar and a reading desk on the other, galleries round the north, west and south walls, an organ in the west gallery, and lighting from two rows of windows on the north and south walls, the lower row to light the aisles and nave, the upper to light the galleries. The font was usually under the west gallery. The only scope for invention which the architect had was in the design of portico and steeple, tower or spire.

Most large towns have at least one example of Commissioners’ Churches, particularly in the north of England, where they were usually Gothic. None to my knowledge except Christ Church, Acton Square, Salford (1831) survived exactly as it was when its architect designed it. This is not because they were badly built. But they were extremely unpopular with the Victorians, who regarded them as cheap and full of shams and unworthy of the new-found dignity of the Anglican liturgy. The usual thing to do was to turn Grecian buildings into ‘Byzantine’ or ‘Lombardic’ fanes, by filling the windows with stained glass, piercing the gallery fronts with fretwork, introducing iron screens at the east end, adding a deeper chancel and putting mosaics in it, and of course cutting down the box-pews, thus ruining the planned proportions of the building and the relation of woodwork to columns supporting the galleries. The architect, Sir Arthur Blomfield, was a specialist in spoiling Commissioners’ Churches in this way. Gothic or Classic churches were ‘corrected’. In later days side chapels were tucked away in aisles originally designed for pews. Organs were invariably moved from the west galleries made for them, and were fitted awkwardly alongside the east end.

One can visualize a Commissioners’ Church as it was first built, by piecing together the various undisturbed parts of these churches in different towns. The Gothic was a matter of decoration, except in St Luke’s new church, Chelsea, London, and not of construction. A Commissioners’ Church will be found in that part of a town where streets have names like Nelson Crescent, Adelaide Place, Regent Square, Brunswick Terrace and Hanover Villas. The streets round it will have the spaciousness of Georgian speculative building, low-terraced houses in brick or stucco with fanlights over the doors, and, until the pernicious campaign against Georgian railings during the Nazi war, there were pleasant cast-iron verandahs on the first floor and simple railings round the planted square. Out of a wide paved space, railed in with Greek or Gothic cast iron according to the style of the building, will rise the Commissioners’ Church, a brick structure with Bath stone dressings, two rows of windows and a noble entrance portico at the west end. Such churches are generally locked today, for the neighbourhood has often ‘gone down’; the genteel late Georgian families who lived there moved into arboured suburbs at the beginning of this century, and their houses have been sub-let in furnished rooms.

But Commissioners’ Churches, which provided worship for nearly five million people, had a dignity and coherence which we can appreciate today now that the merits of Georgian Architecture are recognized. They were the last auditory buildings of the Establishment to be erected for about a century. Through the rest of the 19th century, most new churches might be considered inauditory buildings, places where the ritual of the service could best be appreciated, where sight came first and sound second.

By 1850 began a great period of English church building, which is comparable with the 15th century. Much as we regret the Victorian architect’s usual ‘restoration’ of an old building, when he came to design a new one, he could produce work which was often original and awe-inspiring. To name only a few London churches, All Saints, Margaret Street; St Augustine’s, Kilburn; St James the Less, Victoria; St Columba’s, Haggerston; Holy Trinity, Sloane Street; Holy Redeemer, Clerkenwell; St Michael’s, Camden Town; and St Cyprian’s, Clarence Gate, are some large examples of the period which have survived Prussian bombing. To understand the inspiration behind these churches, we must leave architecture for a while and turn to the architects and the men who influenced them; architects such as Pugin, Street, Butterfield, Pearson, Gilbert Scott, Bodley and the Seddings, and priests such as Newman, Keble, Pusey, Neale, Wilberforce, and later Lowder, Mackonochie and Wainwright.

CHEADLE: ST GILES – one of A. W. N. Pugin’s most complete schemes, a meticulous recreation of medieval Gothic

© Michael Ellis

The Commissioners’ Churches were built to provide more space for the worship of God. But in what way was God to be worshipped? And even, who was God? Those 19th-century liberals who survived the shock of the French Revolution took up a line which we can still find today in the absurd Act inaugurated by R. A. Butler (1944) about the teaching of religion in State Schools. The liberal view was, as Newman described it, ‘the doctrine that there is no positive truth in religion, but that one creed is as good as another.’ This view commended itself to Dissenters in the beginning of the last century, since they saw in it the liberty to expound their doctrines, and perhaps to win the world to believe them. It commended itself to those whom scientific discovery was driving to unwilling agnosticism. And, of course, it commended itself to materialists who had not yet made a dogma of materialism.

In the late Georgian Church there was little of such liberalism. People were divided into Low Church Evangelicals and old-fashioned ‘High and Dry’. By the 1830s the great Evangelical movement was, as W. S. Lilly says, ‘perishing of intellectual inanition’. Beginning, in Apostolic wise, with ‘the foolishness of preaching, it had ended unapostolically in the preaching of foolishness.’ The evangelical tea-parties, revelations, prophecies, jumping, shaking and speaking in strange tongues which went on in England in those days within and without the Church make fascinating reading. But they have left no enduring architectural monument, except for some of the buildings belonging to the Catholic Apostolic Church. The other party in the Church of England, the ‘high and dry’, was orthodox and uninspiring. Once a quarter, after preparing themselves by means of those Queen Anne and Georgian manuals of devotion which we sometimes find bound up in old prayer books, its members moved through the chancel screen on Sacrament Sunday to partake of the outward and visible signs of inward and spiritual grace. Their parsons wore the surplice and the wig, and abhorred change. They were not quite so negative as they are made out to be. There are several instances in the late 18th and early 19th centuries of screens being erected across chancels to shut off from the nave the place where the Sacrament was partaken.

The Church of England at this time drew its ministers from men who were scholars or gentlemen, usually both. Harriet Martineau’s acid biography of Bishop Blomfield (1786–1857) in her Biographical Sketches, rather cattily says: ‘In those days, a divine rose in the Church in one or two ways, – by his classical reputation, or by aristocratic connection. Mr Blomfield was a fine scholar;...’

Let us try to put ourselves into the frame of mind of somebody living in the reign of King William IV. Let us suppose him just come down from Oxford and still in touch with his University. The grand tour was no longer so fashionable. A squire’s son usually went abroad for sport. Few came back with works of art for the adornment of their parks or saloons. Most country house libraries stop at the end of George IV’s reign, except for the addition of sporting books and works of reference on husbandry, law and pedigrees of family and livestock. A studious man, such as we have in mind, would have turned his attention to antiquity and history. The novels of Scott would have given him a taste for England’s past. The antiquarian publications of Britton would have reinforced it. In Gothic England he would have found much to admire. And the people of his village were still the product of agricultural feudalism. Tenantry bobbed, and even artisans touched their hats. Blasphemy shocked people, for many believed that Christ was the Incarnate Son of God.

Our young man would undoubtedly read The Christian Year by the Reverend John Keble (1827). It is hard to see today how this simple and unexciting, oft-reprinted book could have fired so many minds. Perhaps the saintly life of the author, who had thrown up academic honours and comfort to live among simple villagers as their minister, had something to do with it. At any rate, Newman regarded that book as the foundation of the Tractarian movement. The verses of The Christian Year were a series composed to fit in with the feasts, fasts and offices of the Book of Common Prayer. They drew people back to the nature of the Established Church. And the Tracts for the Times which followed, from Keble’s Assize Sermon of 1833 up to Tract XC by Newman on the Thirty-nine Articles in 1841, would certainly influence him greatly. In these he would learn how the Church was finding herself part of the Catholic Church. Although many great men, greatest of all Newman, have left her for the Church of Rome, others remained faithful. Their witness in England in the last century is apparent in the hundreds of churches which were built on Tractarian principles in new suburbs and towns, in the church schools, public and elementary, in the Sisterhood buildings, in the houses of rest erected by good people of the kind one reads about in the novels of Charlotte M. Yonge, who was herself a parishioner and friend of Keble.

English architecture was also beginning a new phase of professionalism in the reign of William IV. Architects had in the past been regarded either as builders or as semi-amateurs who left the details of their designs to masons and plasterers. There had been great architects since the time of Wren. There was also a host of lesser men who in domestic work were pursuing their local styles and imitating the splendid designs of the metropolis, rather as village builders in monastic times had tried to reproduce in village churches the latest styles at the abbeys. But for years now architecture had been becoming a profession. Architects designed buildings and produced their own beautiful, detailed drawings. Less was left to the builder and the gifted amateur. In 1837 the Institute of British Architects was incorporated by Royal Charter. Architects were by now rather more like doctors and lawyers than artists.

The most influential was Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (1812–52), who was said by his doctor to have crammed into his forty years of existence the work of a hundred years. Pugin’s life has been entertainingly described by his contemporary Benjamin Ferrey in Recollections of Augustus Welby Pugin, 1861, and lately his life has been written by Michael Trappes-Lomax, who stresses his Roman Catholicism. Sir Kenneth Clark in The Gothic Revival, the Revd. B. F. L. Clarke in Nineteenth Century Churchbuilders, and John Summerson in an essay in The Architectural Review (April 1948), have all written most illuminatingly about him.

In 1841 Pugin published his Contrasts and his True Principles of Christian Architecture. Herein he caricatured in skilful drawings the false Gothick of the Strawberry Hill type, and lampooned everything that was classical. To contrast with these he had made beautiful shaded drawings of medieval buildings, particularly those of the late 14th century. He did not confine his caricatures to architecture, and peopled the foregrounds with figures. In front of pagan or classical buildings he drew indolent policemen, vulgar tradesmen and miserable beggars; before the medieval buildings he drew vested priests and pious pilgrims. He idealized the middle ages. His drawings were sincere but unfair. The prose accompaniment to them is glowing and witty.

Pugin’s own churches, which were almost all Roman Catholic, are attempts to realize his dreams. But for all the sincerity of their architect, the brass coronals, the jewelled glass by Hardman of Birmingham, the correctly moulded arches and the carefully caned woodwork have a spindly effect. St Chad’s Roman Catholic Cathedral at Birmingham, St Augustine’s Church, Ramsgate, and St Giles’s, Cheadle, are exceptions. It is not in his buildings but in his writing that Pugin had so great an influence on the men of his time.

Pugin is sometimes supposed to have joined the Church of Rome for aesthetic reasons only. It is true that he saw in it the survival of the Middle Ages to which he desired the world to return. But the Roman Catholics of his time were not whole-heartedly in favour of the Gothic style he advocated, and to his annoyance continued to build in the classic style of the continent or else in the plaster-thin Gothick he despised. The Church of England, newly awakened to its Catholicism, took more kindly to his doctrines, so that although he came in for some mild criticism from The Ecclesiologist (the organ first of the Cambridge Camden Society, and from 1845 of Catholic-minded Anglicans in general), Pugin contemplated writing an essay called: ‘An Apology for the separated Church of England since the reign of the Eight Henry. Written with every feeling of Christian charity for her Children, and honour of the glorious men she continued to produce in evil times. By A. Welby Pugin, many years a Catholic-minded son of the Anglican Church, and still an affectionate and loving brother of the true sons of England’s church.’

I do not think it was solely for aesthetic reasons, or even for doctrinal reasons, that Pugin joined the Church of Rome. He possessed what we now call, ‘social conscience’. He deplored the slums he saw building round him. He abhorred the soullessness of machinery, and revered hand craftsmanship. His drawings of industrial towns contrasted with a dream-like Middle Ages, his satire on the wealthy ostentation of a merchant’s house – ‘On one side of the house machicolated parapets, embrasures, bastions, and all the show of strong defence, and round the corner of the building a conservatory leading to the principal rooms, through which a whole company of horsemen might penetrate at one smash into the heart of the mansion! – for who would hammer against nailed portals when he could kick his way through the greenhouse?’ – are summed up in the two principles of Gothic or Christian architecture which he delivered to the world. These are they. ‘First, that there should be no features about a building which are not necessary for convenience, construction, or propriety; second, that all ornament should consist of enrichment of the essential construction of the building.’ Pugin’s principles, and his conviction that the only style that was Christian was Gothic, are fathered by popular opinion on Ruskin. But Ruskin was not fond of Pugin. He disliked his Popery, and he thought little of his buildings. If one must find a successor to Pugin, it is the atheist William Morris. Both men liked simplicity and good craftsmanship. Both had a ‘social conscience’. Pugin dreamed of a Christian world, Morris of a Socialist world, but both their worlds were dreams.

Let us imagine our young man again, now become a Tractarian clergyman. His convictions about how best to honour the God he loves, and how to spread that love among the artisans in the poorer part of his parish, are likely to take form in a new church. And, since he is a Tractarian, it must be a beautiful church. His reading of Pugin, the publications of the Cambridge Camden Society and The Ecclesiologist, will have inspired him. He will have no truck with the cheap Gothic or Norman Revival of the Evangelical school. A pamphlet such as that of Revd. W. Carus Wilson’s Helps to the Building of Churches, Parsonage Houses and Schools (2nd Edition, Kirby Lonsdale, 1842) will have digusted him. Here we find just the sort of thing Pugin satirized: ‘A very neat portable font has been given to the new church at Stonyhurst, which answers every purpose; not requiring even the expense of a stand; as it might be placed, when wanted, on the Communion Table from which the ceremony might be performed. The price is fourteen shillings; and it is to be had at Sharper’s, Pall Mall East, London.’ Such cheese-paring our clergyman would leave to the extreme Protestants who thought ostentation, stained glass, frontals, lecterns and banners smacked of Popery, and who thought with Dean Close of Cheltenham that ‘the Restoration of Churches is the Restoration of Popery’. This explains why, to this day, unrestored churches with box-pews are generally Evangelical and locked. But the Evangelical did not wholly reject Gothic. Ullenhall (Warwicks) and Itchen Stoke (Hants) are Victorian Gothic churches designed to have the Table well away from the East wall and the lectern and pulpit dominant. Ullenhall retains its Protestant arrangement, and this arrangement was originally, we must remember, the ‘High Church’ of the 17th and 18th centuries. The Early English style was regarded as plain and primitive. Very few churches were built in a classic style between 1840 and 1900. The choice before young vicar is no longer Gothic or Classic, but what sort of Gothic?