Betjeman’s Best British Churches

Architects were turning their attention to churches. And the younger men were all for Gothic. Most architects were God-fearing folk of the new middle class. They felt privileged to build churches to the glory of God. Many of them were instructed in theology; they subscribed to The Ecclesiologist and to various learned antiquarian publications. They delighted to discuss the merits of Norman, and Decorated, Early English and Perpendicular, or Early, Middle and Late Pointed, according to which terminology they favoured. In the early ’forties they were still following Pugin. Pugin’s chief Anglican equivalents were Benjamin Ferrey, Carpenter and Gilbert Scott. These men, and many others, were capable of making very good imitations of a medieval fabric. With the aid of the numerous books of measured drawings that were appearing, it was possible to erect almost exact copies of such famous monuments of the Middle Ages as the spire at Louth, the tracery of the Angel Choir at Lincoln, and the roof of Westminster Hall. The scale was different it is true, and architects had no compunction about mixing copies of what they considered the ‘best’ features of old churches in their new ones. They thought that a blend of the best everywhere would make something better still.

LONDON: ALL SAINTS MARGARET STREET – Butterfield’s masterpiece is an industrialised version of Gothic Revival, a medieval sensibility allied to modern materials and methods

© Michael Ellis

The earlier Gothic revival churches, that is to say those of late Georgian times, were in the late 14th-century style. One may see in some prim and spacious Georgian square, brick imitations of King’s College Chapel and Bathstone dressings. But in the late 1840s architects were attaching moral properties to Gothic styles. Pugin had started the idea and his successors surpassed him. Since Gothic was the perfect style, what was the perfect style of Gothic? I do not know who it was who started the theory that early Gothic is crude, middle is perfection, and late is debased . But – certainly from the middle of the 1840s – this theory was held by most of the rising young church architects. Promoters of new churches who could afford it were advised to have something in the Middle Pointed or Decorated style. This is the reason why in mid-Victorian suburbs, while speculative builders were still erecting Italianate stucco mansions, in the last stuccoed gasp of the Georgian classic tradition – South Kensington and Pimlico in London are examples – the spire of Ketton or Louth soars above the chimney-pots, and a sudden break in the Palladian plaster terraces shews the irregular stone front, gabled porch and curvilinear tracery of a church in the Decorated style. Church architecture was setting the fashion which the builders followed, and decades later, even employing church architects (such as Ferrey at Bournemouth), they erected Gothic residences in the new winding avenues of housing estates for the upper middle classes. Most of the work of the late ‘forties and early ‘fifties was in this copying style. When an architect had a sense of proportion, there were often impressive results. Carpenter and his son and their partner Slater were always good. Their Lancing School Chapel must be regarded as one of the finest Gothic buildings of any period in England, and their London church of St Mary Magdalen, Munster Square, so modest outside, is spacious and awe-inspiring within.

The most famous copyist was Gilbert Scott. He and his family have had a great influence on English architecture over the past century. Gilbert Scott was the son of a Buckinghamshire parson, the grandson of the Calvinist clergyman Thomas Scott, whose Commentary on the Bible greatly influenced Newman as a youth. There is no doubt of Scott’s passionate affection for Gothic architecture. He pays a handsome tribute to Pugin’s influence on his mind: ‘Pugin’s articles excited me almost to fury, and I suddenly found myself like a person awakened from a long, feverish dream, which had rendered him unconscious of what was going on about him.’

Our young clergyman would almost certainly have applied to Gilbert Scott for his new church. He would have received designs from Scott’s office. They would have been a safe, correct essay in the middle pointed style, with tower and spire or with bellcot only, according to the price. Scott himself, except when he first started in private practice, may not have had much to do with the design. He collected an enormous staff, and from his office emerged, it is said, over seven hundred and forty buildings between 1847 and 1878 when he died. When one considers that an architect in private practice today thinks himself busy if he has seven new buildings to do in a decade, it seems probable that Scott eventually became little more than an overseer of all but his most important work. His ‘restorations’ were numerous and usually disastrous.

Yet Scott, who was eventually knighted for his vast output, had a style of his own – a square abacus to his columns, Plate tracery in the windows, much stone foliage mixed up with heads, and for east or west windows, three equal lancets with a round window above them. In five churches of his, St Giles, Camberwell; St George’s, Doncaster; Leafield, Oxon; Bradfield, Berks, and St Anne, Alderney, I can trace it clearly. He liked to build something big. He dispensed with a chancel screen. Instead of this, he often interposed between the congregation in the nave and the rich chancel, a tower or transept crossing which was either darker or lighter than the parts it separated. Add to this a sure sense of proportion and a workmanlike use of stone, and the dull mechanical details of his work are forgotten in the mystery and splendour of the interior effect. Scott realized some of Pugin’s dreams for him. But he never did more. He was at heart a copyist and not a thinker in Gothic.

Church architecture by the ’fifties was very much an affair of personalities. The big London men and a few in the provinces had their individual styles. As Sir Charles Nicholson remarked in his comments on Henry Woodyer’s beautiful building St Michael’s College, Tenbury (1856), which was designed as a church choir school: ‘It was never, of course, intended that the College should be mistaken for anything other than a 19th-century building: for Gothic revival architects did not attempt such follies, though their enemies accused them of doing so.’ What is true of St Michael’s College, Tenbury, is true also of most of the churches built in England after 1850. The chief of those architects who ‘thought in Gothic’ are listed below.

William Butterfield (1814–1900) was the most severe and interesting of them. He first startled the world in 1849 with his design for All Saints, Margaret Street, London, built on the cramped site of an 18th-century proprietary chapel where lights had been used on the altar since 1839, and a sung celebration of the Holy Communion introduced. All Saints embodies architectural theories which Butterfield employed in most of his other churches throughout his long life. It is constructed of the material which builders in the district were accustomed to use, which in London at that time was brick. Since bricks do not lend themselves to the carving which is expected of a Gothic building, Butterfield varied his flat brick surfaces with bands of colour, both within and without. In those days the erroneous impression prevailed that Gothic decoration grew more elaborate the higher it was on a building. The patterns of bricks in Butterfield’s buildings grew, therefore, more diversified and frequent towards the tops of walls, towers and steeples. But their arrangement is not usually capricious as it is in the work of some of the rather comic church architects who copied him, like Bassett Keeling. Where walls supported a great weight, they were striped horizontally, where they were mere screen walls, diaper patterns of bricks were introduced. Inside his churches Butterfield delighted to use every coloured stone, marble and other material he could find for the money at his disposal. He was a severely practical man, and a planner and constructor first. His decoration was meant to emphasize his construction.

The plan of All Saints is in the latest Tractarian manner of its time. The high altar is visible from every part of the church. Indeed to this day not even the delicate and marked style of Sir Ninian Comper’s side altar in the north aisle takes one’s eye from the chancel. Butterfield disapproved of side altars and never made provision for them in his churches. The chancel is the richest part of the building, and the chancel arch, higher than the arcades of the nave, gives it an effect of greater loftiness than it possesses. There is, of course, no screen. The other prominent feature of any Butterfield church is the font. That sentence in the Catechism on the number of Sacraments, ‘Two only, as generally necessary to salvation, that is to say Baptism, and the Supper of the Lord’, is almost spoken aloud by a Butterfield church; altar and font are the chief things we see. But when we look up at arches and roofs, we see Butterfield the builder with his delight in construction. His roofs are described by that fine writer Sir John Summerson as ‘like huge, ingenious toys’. The phrase is as memorable as all Butterfield’s roofs, of which the ingenuity and variety seem to have been the only sportiveness he permitted himself.

In person Butterfield was a silent, forbidding man who looked like Mr Gladstone. He was an earnest Tractarian with a horror of everything outside the liturgy of the Book of Common Prayer. Except for one Noncomformist chapel in Bristol, designed when he was a youth, and unlike the rest of his work, he built only for Tractarians. He supplied no attractive drawings to tempt clients. He was a strong disciplinarian in his office, and on the building site, scaffolding and ladders had to be dusted before he ascended to see the work in progress. He was averse to all publicity and show, and had little to do with any other architects. People had to take Butterfield or leave him. And so must we. Yet no one who has an eye for plan, construction and that sense of proportion which is the essential of all good architecture, can see a Butterfield church without being compelled to admire it, even if he cannot like it.

George Edmund Street, R.A. (1824–81), is chiefly remembered now for the Law Courts in London. He was in Gilbert Scott’s office before setting up on his own. Early in his career he received the patronage of such distinguished High Churchmen as Prynne, Butler of Wantage, and Bishop Wilberforce of Oxford. Street himself was a Tractarian, singing in the choir at Wantage and disapproving of ritual without doctrine. The churches he built in the late ‘fifties and throughout the ’sixties, often with schools and parsonages alongside them, are like his character straightforward and convinced. They are shorn of those ‘picturesque’ details beloved of the usual run of architects of the time. The plan of Street’s buildings is immediately apparent from the exterior. Some of his village schools of local stone built early in his career in the Oxford Diocese are so simple and well-proportioned, and fit so naturally into the landscape, that they might be the sophisticated Cotswold work of such 1900 architects as Ernest Gimson and F. L. Griggs. Street’s churches are built on the same principles as those of Butterfield, one altar only, and that visible from all parts of the church, a rich east end, and much westward light into the nave. Street had a sure sense of proportion, very much his own; his work, whether it is a lectern or a pulpit or a spire, is massive, and there is nothing mean about it nor over-decorated. This massive quality of his work made Street a bad restorer of old buildings, for he would boldly pull down a chancel and rebuild it in his own style. He was a great enthusiast for the arts and crafts. With his own hands he is said to have made the wooden staircase for West Challow Vicarage in Berkshire. His ironwork was drawn out in section as well as outline, and there were some caustic comments written by him in the margin of his copy of Gilbert Scott’s Personal and Professional Recollections (in the RIBA Library) where Scott confesses to leaving the detail of his ironwork to Skidmore of Coventry, the manufacturer. Street was an able sketcher of architecture, and clearly a man who could fire his pupils with his own enthusiasm, even though he never allowed those pupils a free hand in design, doing everything down to the smallest details himself. Street’s influence on English architecture is properly appreciated in H. S. Goodhart Rendel’s English Architecture Since the Regency. It comes down to us through his pupils, among whom were Philip Webb and Norman Shaw, whose domestic architecture brought about the small house of today, William Morris, to whom the Arts and Crafts Movement owes so much, and J. D. Sedding, the church architect and craftsman.

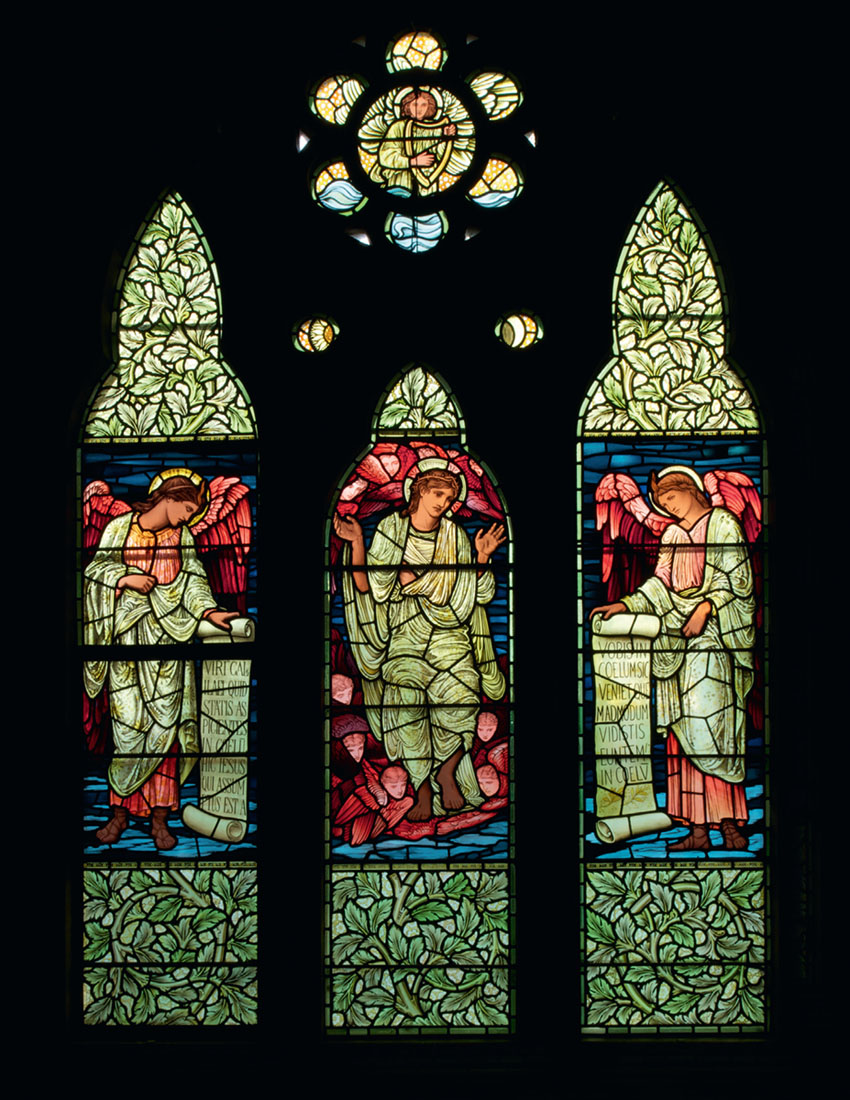

WATERFORD: ST MICHAEL AND ALL ANGELS – Morris & Co. produced much of the glass in this church, some designed by William Morris and some, such as this example, by Burne-Jones

© Michael Ellis

The third of the great mid-Victorian church builders was John Loughborough Pearson (1817–97). His later buildings are of all Victorian churches those we like best today. He was, like Street and Butterfield, a Tractarian. Before designing a building he gave himself to prayer and receiving the Sacrament. He seems to have been a more ‘advanced’ clergyman than his two comparable contemporaries, for in his later churches he made ample provision for side altars, and even for a tabernacle for the reservation of the Blessed Sacrament. Pearson was articled in Durham to Ignatius Bonomi, the son of an elegant 18th-century architect. His early work in Yorkshire is competent copying of the medieval, and just distinguishable from the work of Gilbert Scott. But somewhere about 1860 he paid a visit to France, and early French Gothic vaulting seems to have transformed him. He built St Peter’s, Vauxhall, London, in 1862. Like most of his later work it is a cruciform building with brick vaulting throughout and with a clerestory. St Peter’s seems to have been the pattern of which all his subsequent churches were slight variants. Sometimes he threw out side chapels, sometimes he made aisles under buttresses. The Pearson style was an Early English Gothic with deep mouldings and sharply-pointed arches; brick was usually employed for walls and vaulting, stone for ribs, columns, arches and window tracery. Pearson also took great trouble with skyline, and his spires, fleches and roofs form beautiful groups from any angle.

One more individualistic Gothic revivalist was William Burges (1827–81), who was as much a domestic architect and a furniture designer as an ecclesiastical man. He delighted in colour and quaintness, but being the son of an engineer, his work had a solidity of structure which saved it from ostentation. His east end of Waltham Abbey and his cathedral of St Finbar, Cork, are his most beautiful church work, though Skelton and Studley Royal, both in Yorkshire, are overpowering in their rich colour and decoration, and very original in an early French Gothic manner.

Neither Butterfield, Street, Pearson nor Burges would have thought of copying old precedents. They had styles of their own which they had devised for themselves, continuing from the medieval Gothic but not copying it.

These big men had their imitators: Bassett Keeling who reproduced the wildest excesses of the polychromatic brick style and mixed it with cast-iron construction; S. S. Teulon who, in his youth, did the same thing; E. Buckton Lamb who invented a style of his own; Henry Woodyer who had a fanciful, spindly Gothic style which is original and marked; William White and Henry Clutton, both of whom produced churches, strong and modern for their times; Ewan Christian, the Evangelical architect, who could imitate the style of Pearson; or that best of the lesser men, James Brooks who built several ‘big-boned’ churches in East London in a plainer Pearson-esque manner. There was also the scholarly work in Italian Gothic of E. W. Godwin, and Sir Arthur Blomfield could turn out an impressive church in almost any style.

There is no doubt that until about 1870 the impetus of vigorous Victorian architecture went into church building. Churches took the lead in construction and in use of materials. They employed the artists, and many of the best pictures of the time had sacred subjects. The difficulties in which artists found themselves, torn between Anglo-Catholicism, Romanism and Ruskin’s Protestantism, is described well in John Steegman’s Consort of Taste.

After the ‘seventies, Norman Shaw, himself a High Churchman, became the leading domestic architect. The younger architects turned their invention to house design and building small houses for people of moderate income. Bedford Park was laid out by Norman Shaw in 1878. It was a revolution – a cluster of picturesque houses for artistic suburbanites. And from this time onwards we have a series of artistic churches, less vulgar and vigorous than the work of the now ageing great men, but in their way distinguished: slender, tapering work, palely enriched within in Burne-Jonesian greens and browns. The Middle Pointed or Decorated style and variants of it were no longer thought the only correct styles. People began to admire what was ‘late’ and what was ‘English’, and the neglected glory of Perpendicular, long called ‘debased’, was revived, and even the Renaissance style was used. For as the Reverend B. F. L. Clarke says in his Church Builders of the Nineteenth Century, ‘the question of Style was coming to be regarded as being of small importance’.

The last quarter of the 19th century was a time when the Tractarian movement firmly established itself. Of the eight Religious Communities for men of the Anglican Church, six were of the 1890s, and one, the ‘Cowley Fathers’ (Society of St John the Evangelist), was founded in 1865. Of the forty-five Communities for women, the first two, the Society of the Holy and Undivided Trinity and the Society of the Most Holy Trinity, Ascot, were founded in 1845, and well over half the rest are of Victorian origin. There are now in the Church of England more religious Communities than there were in medieval England, and this does not include Communities in Scotland, Wales, Ireland, America, Asia, Africa and Australia.

This was a time when the church was concerning herself with social problems, and building many new churches in England as well as establishing dioceses abroad. Many, and often ugly, little churches were built of brick in brand new suburbs. Cathedral-like buildings, subscribed for by the pious from wealthy parishes, were built in the slums. At the back of Crockford’s Clerical Directory there is an index of English parishes with the dates of their formation. If you look up an average industrial town with, say, ten churches, you will find that the majority will have been built during the last half of the 19th century. Oldest will be the parish church, probably medieval. Next there will be a late Georgian church built by the Commissioners. Then there will be three built between 1850 and 1870, three built between 1870 and 1900, and two since then, probably after the 1914 war and in new suburbs.

It is entertaining, and not completely safe, to generalize on the inner story of the Church and its building in Victorian and later times. In, let us say, 1850, the vicar of the parish church had become a little old for active work, and left much to his curates. His churchmanship took the form mainly of support for the Establishment and hostility to Dissent. The word ‘Dissenters’ applied to Nonconformists always had a faint note of contempt. Methodists and Baptists were building chapels all over the rapidly growing town. Their religion of personal experience of salvation, of hymn-singing, ejaculations of praise; the promise of a golden heaven after death as a reward for a sad life down here in the crowded misery of back streets, disease and gnawing poverty; their weekday socials and clubs which welded the membership of the chapels in a Puritan bond of teetotalism, and non-gambling, non-smoking and welldoing: these had an appeal which today is largely dispersed into the manufactured day-dreams of the cinema and the less useful social life of the dance hall and sports club. Chapels were crowded, gas-lights flamed on popular preachers, and steamy windows resounded to the cries of ‘Alleluia, Jesus saves!’ A simple ceremony like total immersion or Breaking of Bread was something all the tired and poor could easily understand, after their long hours of misery in gloomy mills. Above all, the Nonconformists turned people’s minds and hearts to Jesus as a personal Friend of all, especially the poor. Many a pale mechanic and many a drunkard’s wife could remember the very hour of the very day on which, in that street or at that meeting, or by that building, conviction came of the truth of the Gospel, that Jesus was Christ. Then with what flaming heart he or she came to the chapel, and how fervently testified to the message of salvation and cast off the old life of sin.

CARSHALTON: ALL SAINTS – Ninian Comper produced some of his finest work in this surburban London church, including this gilded and painted triptych for the high altar

© Michael Ellis

Beside these simple and genuine experiences of the love of Christ, the old-established Church with its system of pew rents, and set prayers and carefully-guarded sacraments, must have seemed wicked mumbo-jumbo. No wonder the old Vicar was worried about the Dissenters. His parish was increasing by thousands as the factories boomed and the ships took our merchandise across the seas, but his parishioners were not coming to church in proportion. He had no objection therefore when the new Bishop, filled with the zeal for building which seems to have filled all Victorian bishops, decided to form two new parishes out of his own, the original parish of the little village which had become a town in less than a century. The usual method was adopted. Two clergymen were licensed to start the church life of the two new districts. These men were young; one was no doubt a Tractarian; the other was perhaps fired with the Christian Socialism of Charles Kingsley and F. D. Maurice. Neither was much concerned with the establishment of churches as bulwarks against Dissenters, but rather as houses of God among ignorant Pagans, where the Gospel might be heard, the Sacraments administered, want relieved, injustice righted and ignorance dispelled. First came the mission-room, a room licensed for services in the clergyman’s lodging, then there was the school, at first a room for Sunday school only, and then came the mission church made of corrugated iron. Then there was an appeal for a church school and for a permanent church. For this church the once young clergyman, now worn after ten years’ work, would apply to the Incorporated Church Building Society, and to the Church Building Fund of his own diocese; he would raise money among his poor parishioners, he would give his own money (this was a time when priests were frequently men of means), and pay his own stipend as well. The site for the church would be given by a local landowner, and who knows but that some rich manufacturer whose works were in the parish would subscribe. Whatever their Churchmanship, the new parishes formed in the ‘fifties generally had their own church within twenty years.

All this while the Commissioners’ Church in the town, that Greek Revival building among the genteel squares where still lived the doctors, attorneys and merchants, had an Evangelical congregation and disapproved of the old ‘high and dry’ vicar of the parish church. The congregation and incumbent disapproved still more of the goings on of the Tractarian priest in charge of one of the two new districts. He lit two candles on the Table which he called an ‘altar’, at the service of the Lord’s Supper he stood with his back to the congregation instead of at the north end of the Table, he wore a coloured stole over his gown. He was worse than the Pope of Rome or almost as bad. The ignorant artisans were being turned into Roman Catholics. The pure Gospel of the Reformation must be brought to them. So a rival church was built in the Tractarian parish, financed by the Evangelical church people of the town, and from outside by many loyal Britons who throughout England, like Queen Victoria herself, were deploring the Romish tendency in the Established Church.