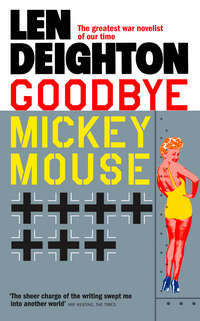

Goodbye Mickey Mouse

‘Then why did you leave?’

‘The government said domestics had to be in war jobs. Not that I know what I’m doing to win the war here, helping the cashier with the wages and getting tea for all those lazy reporters.’

‘Don’t be sad,’ Victoria said. ‘It’s Christmas Eve.’

Vera nodded and smiled, but didn’t look any happier. ‘You’re coming with me tonight, aren’t you?’

‘I have to go home to change first.’ She tried to keep her voice level—she didn’t want to reveal how eager she was to see Jamie again—but Vera’s shrewd eyes saw through her.

‘What are you wearing?’ Vera asked briskly. ‘A long dress?’

‘My mother’s yellow silk, I had it altered. The sister of that girl in the personnel office did it. She shortened it, made big floppy sleeves from what she’d taken off the bottom, and put a tie-belt on it.’

‘Vince must be sick of seeing me in that green dress,’ Vera said. ‘But I’ve got nothing else. He’s offered to buy me something, but I’ve got no ration coupons.’

‘You look wonderful in the green dress, Vera.’ It was true, she did.

‘Vince is trying to wangle me a parachute. A whole parachute! Vince says they’re pure silk, but even if they’re nylon it would be something!’ She picked up the outgoing mail from the tray as if suddenly remembering her work. ‘Victoria,’ she asked in a low voice as if the answer was really important to her. ‘Do you hate parties?’

‘I’m sure it will be lovely, Vera,’ she answered evasively, for the truth of it was that she did hate parties.

‘They’ll all be strangers. Vince has invited lots of men from the base and they’ll have girls with them. There’s no telling who might see me there…and start tongues wagging.’

‘Cross that bridge when you come to it,’ Victoria advised. So Vera didn’t realize that her extramarital associations were already a subject for endless discussion in the typing pool downstairs. Vera wears the new Utility knickers, Victoria had overheard a girl say; one Yank and they’re off. The others had laughed.

Vera stood in the doorway looking at her friend quizzically. ‘You never cry, do you? I can’t imagine you crying.’

‘I’m not the crying type,’ Victoria said. ‘I swear instead.’

Vera nodded. ‘All you girls who’ve been to university swear,’ she said, and smiled. ‘I won’t wait for you tonight, I’ll go on ahead. I know what Vince is like. If I’m not there and he sees some other girl he fancies, he’ll grab her.’

Victoria could think of no reassuring answer.

The noise could be heard from as far away as the river. There were taxis outside the door as well as an RAF officer holding a fur coat and handbag for some absent girl.

Victoria didn’t have to knock at the door. She’d raised her hand to the brass knocker when the caretaker swung the door open, spilling some of his whisky as he swept back the curtain. ‘Quickly, miss, careful of the blackout.’ He said it carefully, but his smile and unfocused eyes betrayed his drunkenness.

The house was packed with people. Some of the table lights had been broken, others shielded with coloured paper, but there was enough light to see that the drawing room had become a dance floor. Couples were crowded together too tightly to do anything but hug rhythmically in the semi-darkness.

Among the American uniforms she could see a few RAF officers and some Polish pilots. Men without girls were seated on the stairs, drinking from bottles and arguing about the coming invasion and what was happening ‘back home’. There were low wolf whistles and appreciative growls as Victoria climbed the stairs, picking her way between the men. More than one fondled her legs under the pretence of steadying her.

She found Jamie and Vince Madigan on the landing, trying to revive a female guest who’d lost consciousness after drinking too much of a mixture that had cherries and dried mint floating in it. Described as fruit punch, it smelled like medicinal alcohol sweetened with honey. Victoria decided not to drink any of it.

‘She needs air,’ Vera said, appearing from another room. ‘Take her downstairs and out into the street.’ Vera seemed to be in command. Although she was always saying how she hated crowds and parties she thrived on them.

‘She’s Boogie’s girlfriend,’ explained Jamie. ‘He’s a pilot…the one playing the piano downstairs.’ Victoria took his arm, but he seemed too busy to notice. Vera smiled to indicate how much she liked Victoria’s very pale yellow dress, and both women watched dispassionately as two officers in brown leather flying jackets carried the limp girl downstairs with more enthusiasm than tenderness. The men on the stairs hummed the Funeral March as the unfortunate casualty was bundled away.

‘Did you invite all these people?’ Victoria asked.

Jamie shook his head. ‘They’re mostly friends of Vince, as well as a few who wandered in off the street. What are you drinking?’

‘Not the fruit punch.’ Was it too much to expect that he would notice her hair, swept back into a chignon, and the high-neckline dress with its standing collar and the tiny black bow?

‘Whisky, okay?’ He was pouring it before she could answer, and then he stuck the bottle back into the side pocket of his uniform jacket. His eyes were bright and restless as he kept looking round to see who else was there. He wasn’t drunk, but she guessed he’d started drinking early that day. ‘How’s that?’ He held up the half-filled glass of whisky.

Victoria had never drunk undiluted whisky before, but she didn’t want to give him any reason for leaving her. Even while they stood there, she was continually being patted and stroked by men who passed, looking for food or drink or the bathroom. ‘It’s lovely,’ she said, and brought the whisky to her lips without drinking any. It had a curious smell.

He noticed her sniffing at it. ‘Bourbon,’ he explained. ‘It’s made from corn.’

He was watching her; she tasted her drink and thought it smelled remarkably like damp cardboard. ‘Delicious,’ she said.

‘I can see that you go for it,’ Jamie mocked.

Victoria smiled. He still hadn’t kissed her, but at least there was no sign of any other girl with him. He pulled her closer to make way for an American naval officer who was elbowing his way to the bathroom. Finding it locked, he hammered on the door and yelled, ‘Hurry up in there! This is an emergency!’ Someone laughed, and a man sitting on the next staircase said, ‘He’s got a girl in there with him. I’d try the one upstairs if you’re in a hurry, Mac.’ The sailor cursed and hurried upstairs past him.

Victoria looked at Jamie, trying to enjoy the party. ‘Are most of them from your squadron?’

‘That’s Colonel Dan over there. He’s the Group Commander, the big cheese himself.’

Victoria looked round to see a short cheerful man with a large nose and messy fair hair talking earnestly to a tall dark girl with a floral-patterned turban hat and a black velvet cocktail dress.

‘Is that his wife?’

‘She’s one of the chorus from the Windmill Theatre. They gave a show on base last month—before I got here.’

‘Was it an American general who said war is hell?’

‘And that’s Major Tucker.’ The Major was standing near the stairs drinking from his own silver hip flask and scowling disapproval. Victoria felt a common bond with him but did not say so.

Jamie tightened his hold on her shoulder, but only in order to pull her aside to make way for a middle-aged sergeant who was carrying a crate of gin upstairs and into a room that was being converted into a bar. ‘Thanks for the invite, Captain,’ said the sergeant, out of breath.

‘Good to see you here, Sergeant Boyer,’ said Jamie.

Harry Boyer’s arrival with the gin was greeted by loud cheers. Downstairs, Boogie and the musicians he’d collected for the night began to play ‘Bless ’Em All’, to which the dancers jumped up and down in unison.

‘You hate it, Vicky. I can tell by your face.’

‘No,’ she yelled, ‘it’s really fun.’ By now the whole house was shaking with the vibration of the dancers downstairs. ‘But is there anywhere to sit down?’ Her yellow shoes had never been particularly comfortable, and she’d slipped them from her heels for a moment.

‘Let’s try upstairs,’ Jamie said, and plunged into the crowd. She tried to follow, but with drink in one hand and shoes loosened she couldn’t keep up with him. One shoe came off and only with some difficulty could she get everyone to stand back far enough for her to find it again. When she did, there was the black mark of a boot across the yellow silk, and one strap torn loose. They were the last pair of pre-war shoes in her wardrobe. She told herself to laugh, or at least keep her sense of proportion, but she wanted to scream.

‘If you hate it, say so,’ said Jamie sharply as she reached him at the bottom of the stairs.

She wondered what would happen if she did tell him how unhappy she was, and decided not the take the chance. ‘Why don’t we dance?’ she said. At least she’d feel his arms around her.

If she was trying to find the limit to James Farebrother’s skills and talents, inviting him to dance provided it. Even in that crush, with the tireless Boogie playing his own dreamy version of ‘Moonlight Becomes You’, Jamie trod on her toes—especially painful as she’d decided to dance in stockinged feet rather than risk the final destruction of her shoes.

‘I’m no great shakes at dancing,’ he said finally. ‘Maybe we should call it quits.’

He found a place on the sofa, but they’d only been sitting there a few minutes when a lieutenant arrived with a message asking Jamie to go upstairs to help Vince. Jamie offered her his apologies, but she feared he was secretly pleased to get away from her. She regretted her flash of bad temper, but she’d so wanted the evening to be perfect.

‘Promise you won’t move?’ Jamie squeezed her arm. She nodded and he planted a kiss on her forehead as though she were a docile infant.

The newly arrived lieutenant dropped heavily into the place Jamie had vacated beside her. ‘Known Jamie long?’

She looked at him. He was a handsome boy trying to grow a moustache. He had a suntanned sort of complexion, with jet-black wavy hair and long sideburns that completed the Latin effect for which he obviously strove. ‘Yes, I’ve known Jamie a long time,’ she said.

He smiled to reveal flashing white teeth. His battered cap was still on his head, but he pushed it well back as if to see her better. He was chewing gum and smoking at the same time. He took the cigarette from his mouth and flicked it towards the fireplace without bothering to look where it went. ‘Jamie only just arrived in Europe,’ he said. ‘My name’s Morse, people call me Mickey Mouse.’

Victoria smiled and said nothing.

‘So you’re a liar. Slow dissolve.’

‘And you’re no gentleman.’

He slapped his thigh and laughed. ‘Are you ever right, lady.’

They were crushed tight together, and although she tried to make more room between them, it wasn’t possible.

‘Gum?’

‘No, thanks.’

‘Where did Jamie meet a classy broad like you?’ he asked. ‘You’re not the kind of lady who hangs around the Red Cross Club on Trumpington Street.’

‘Really?’

‘Rilly! Yes, rilly.’

‘I’m surprised you’ve never noticed me there,’ said Victoria.

MM grinned and tore the corner from a packet of Camels before offering them to her. She never smoked, but on impulse took one. He lit it for her. ‘You Jamie’s girl?’

‘Yes.’ It seemed the simplest way of avoiding further advances. ‘What’s happened to Captain Madigan?’

‘Nothing’s happened to Captain Madigan, lady, and nothing is going to happen to him. Vince is smart—he’s a paddlefoot. He stays on the ground and waltzes the ladies. We’re the dummies who get our tails shot off.’

‘I mean what’s happened now?’ said Victoria. ‘What does he want Jamie for?’ She inhaled on the cigarette and it made her cough.

‘Madigan needs close escort,’ said MM vaguely.

Victoria got to her feet and looked for the door.

‘Lights! Action! Camera!’ said MM, holding thumbs and forefingers as if to frame a camera shot. ‘Where are you going, lady?’

‘I’m going,’ said Victoria, ‘to what you Americans so delicately call the powder room.’

‘I’ll save the place here for you.’

‘Please don’t bother,’ said Victoria. MM chuckled.

She made her way past the musicians and started up the stairs. A lot of drinking had taken place since the last time she’d struggled up through the people sitting on the staircase. They were mostly couples now, locked in tight embraces and oblivious to her pushing past them.

On the upper landing there were two officers sprawled full-length and snoring loudly. A girl was going through the pockets of one of them. She straightened up when she saw Victoria. ‘I’m just trying to find enough for my taxi fare home, honey,’ she announced in the broad accent of south London.

Victoria stepped past without replying. The middle-aged man whom Jamie had called Sergeant Boyer was leaning against the wall inside the first room. He was in his shirt sleeves and wore no tie. He was watching Colonel Dan about to throw a pair of dice against the wall. There was a huge pile of pound notes on the floor and as her eyes became accustomed to the gloom Victoria could see that there were other men there too, all holding wads of money.

‘Come on, baby,’ Colonel Dan yelled into the confines of his clenched fist before throwing the dice. ‘Snake eyes!’ he screamed as they came to rest. There was pandemonium all around, and Victoria was almost knocked off her feet as the Colonel stooped to pick up the dice and lost his balance to fall against her. ‘Oops, sorry, Ma’am.’

She found Jamie on the next floor. He was holding tightly to the bare upper arms of a brassy-looking girl in a shiny grey dress that was cut too low in the front and too tight across the bottom. ‘You’ve got to be sensible,’ Jamie was telling her. ‘There’s no sense in making a scene. These things happen, it’s the war.’

The girl’s eye make-up had smudged with her tears and there were streaks of black down her cheeks. ‘For Christ’s sake, spare me that,’ she said bitterly. ‘You bloody Yanks don’t have to tell me about the war. We were bombed out of my mum’s house years before Pearl bloody Harbor.’

She noticed Vince Madigan was wearing a short Ike jacket complete with a row of medals and silver wings. He too was trying to reason with the tearful girl. ‘Let me walk you to Market Hill…we’ll find a cab and get you home.’

The girl ignored him. To Jamie she said, ‘You think I’m drunk, don’t you?’

From downstairs there came some spirited rebel yells, and the piano struck up the resounding chords of ‘Dixie’. Suddenly Jamie noticed Victoria watching them. ‘Oh, Victoria!’ he said.

‘Oh, Victoria,’ parroted the girl. ‘Whatever have you done with poor Prince Albert?’ She gave a short bitter laugh.

Jamie let go of the girl and turned to Victoria, smiling as if in apology. ‘It’s one of Vince’s friends,’ he explained quietly. ‘She’s threatening to tear Vera to pieces.’ From downstairs came a chorus of joyful voices: ‘In Dixie land, I’ll take my stand, to live and dieeee in Dixie…’

Vince Madigan moved closer to the girl in the grey dress and began talking to her softly, in the manner prescribed for an excited horse. Now that the light was on her she looked no more than eighteen, younger perhaps. The desperate stare had gone now; she was just a sad child. She raised a large red hand to stifle a belch.

‘Or was it you who invited one girl too many?’ said Victoria coldly.

‘She’s not my type,’ said Jamie amiably.

Over Jamie’s shoulder Victoria saw Madigan take the girl in a tight embrace and caress her hungrily. Victoria turned to avoid Jamie’s kiss. ‘Not now,’ she said, ‘not here.’

‘I think I need a drink,’ Jamie said, standing back from her. ‘I’ve had about as much as I can take for one day.’

‘You have!’ said Victoria angrily.

‘I didn’t mean enough of you.’

‘Would you take me home?’

‘Wait just a few minutes more,’ said Jamie. ‘My buddy Charlie Stigg still might get here. I told you I’d invited him.’

‘Then I’ll go home alone,’ she said. Jamie took her arm. ‘You’d better help Captain Madigan,’ she said, pulling herself free. ‘I think his lady friend is about to vomit.’

The girl was holding on to the balustrade and bending forward to retch at the stair carpet.

Victoria pushed her way downstairs and found her coat where it had fallen to the floor under a mountain of khaki overcoats. She glimpsed Vera standing with MM to watch the men who had climbed on top of the piano. One of them, Earl Koenige, was waving the Confederate flag. ‘Look awaay, look awaay, look awaay, Dixie laand!’

She tried to catch Vera’s eye to tell her she was leaving, but Vera had eyes for no one but her newfound lieutenant. She was cuddling him tightly. That was the trouble with Vera; for her, men were just men, interchangeable commodities like silk stockings, pet canaries, or books from a library. Any man who would give her a good time was Mr Right for Vera. She wasn’t looking for a husband, she had one already.

Victoria had no trouble finding a taxi—they were arriving at the house in Jesus Lane every few minutes, bringing more and more people to the party.

She got back home just as the rain began. It was an old Victorian mansion, elaborate with neo-Gothic towers and stained-glass windows. Its dark shape behind the wind-tossed trees did little to raise her spirits as she hurried down the gravel path in the quickening rain. The house was cold and empty, but she closed the carved oak door behind her with a thankful sigh. Sometimes she almost envied Vera those histrionic sobs, lace handkerchief delicately applied to her face without smudging her make-up. Vera always seemed so completely revived afterwards—a release which tonight Victoria needed as never before. But still she didn’t cry.

She walked through the hall and up the grandiose staircase. She would go to the place where she always had to be when unhappy, her sanctum at the very top of the house. She passed the door of her parents’ bedroom and the storeroom that had once been her nursery. On the next floor, she passed the maid’s room, empty now that they no longer had living-in servants. She passed the locked door of her brother’s room and the doors of the toy cupboard, their pasted-on flower pictures now faded and falling.

From the top corridor window she looked down at the dark garden and the tennis court, covered for winter. She couldn’t get used to the emptiness of the house and found herself listening for her mother’s voice or her father’s clumsy cello playing.

Thankfully she went into her bedroom and closed the door behind her. Here at least she could be herself. A pretty row of dolls eyed her from the chest of drawers where they sat among her hairbrushes, but the balding teddy bear had fallen, and was sprawled, limbs asunder, on the floor. She picked him up before running a bath and undressing with the same studied care she gave to everything. She put her dress on its hanger and fitted trees in the battered yellow shoes before placing them in the rack.

‘A museum’ her mother called it derisively, but Victoria refused to let any of it go. She would keep it all—the butterfly collection in its frame on the wall, the doll’s house and her box of seabirds’ eggs. She ran her finger along the children’s books. Enid Blyton to Richmal Crompton, as well as her huge scrapbooks. She was determined to keep it all for ever, no matter how they teased her.

She switched on the electric fire, took off the rest of her clothes, and wiped off her make-up before getting into the hot bath. Sitting in the warm, scented water, the taste of bourbon on her tongue and too much cold cream on her face, she tried to remember everything he’d said to her, searching for implications of love or rejection. The wireless was playing sweet music, but suddenly it ended and the unmistakably accented voice of the American Forces Network announcer wished all listeners a happy Christmas and victorious New Year. ‘Go to hell,’ Victoria told him, and he played more Duke Ellington.

She was drying herself when the doorbell rang. Carol singers? Party-goers looking for another address? It rang again. She put on a dressing gown and ran downstairs. Immediately she noticed the envelope that had been pushed into the letter box. Caught by its corner, the envelope was addressed to a military box number and had been opened and emptied. She turned it over and found scribbled on the back, ‘I’m sorry, darling. Jamie.’

She pulled the robe round her shoulders and opened the door. It was dark in the garden and raining heavily—the trees were loud with the sound. ‘Jamie?’ She thought she saw a man sheltering under the holly trees. ‘Is it you, Jamie?’

‘It all went wrong tonight, darling. My fault.’

‘You’d better come inside.’

‘I couldn’t get a cab. I was going to borrow MM’s motorcycle, but he went off somewhere with Vera.’

‘You’re soaking wet. Hurry, the blackout.’

‘I always forget about the blackout,’ he said. The water was running off the leather visor of his cap and down his face. She could feel the rain from his coat dripping onto her bare feet. ‘I waited in Market Hill, but once the rain started everyone wanted cabs.’

‘You walked? You fool!’ She laughed with joy and embraced him, cold and wet as he was.

‘I think I love you, Vicky.’

‘A note of doubt?’ she teased. ‘Have you learned nothing from Vince?’

He laughed. ‘I love you.’

‘I love you, Jamie. Let’s never quarrel again.’

‘Not ever. I promise.’

They were childish promises, but only childlike pledges are proper to the simple truth of love. She loved him with a desperation she’d never known before, but she took him to her bed for the same prosaic reason that has motivated so many other women—she could not bear to dispel the image of herself in love.

Afterwards he said nothing for what seemed an age. She knew he was staring at the ceiling, his body so still that she could hear his heartbeats. ‘Are you awake?’ she said.

He stretched out his arm to hold her closer. ‘Yes, I’m awake.’

‘It’s Christmas Day.’

He leaned over and greeted her with a gentle but perfunctory kiss.

‘Are you married?’ she asked, making it as casual as possible.

He laughed. ‘Lousy timing, Victoria,’ he said. Then, aware of her anxiety, he held up hands bare except for a class ring. ‘Not married, nor engaged, not even dating regularly.’

‘You’re making fun of me.’

‘Of course I am.’

‘That girl…’

‘She was very sick. It was the fruit punch, it put a lot of people out of action. Vince threw everything he could find into it.’

‘Who was she?’

‘Vince met her last week. She works in the laundry. He made me promise not to tell you she was there, he knew you’d feel bound to tell Vera.’ He turned over to look into her eyes. ‘You must guess what Vince is like by now. He’s everything a girl’s mother warns her about.’

‘He’s not a flyer, is he?’

‘No. He’s the PRO, the Public Relations Officer. He buys drinks for reporters and takes them round the base and sends them press handouts.’

‘He told Vera he’d flown twenty missions over Germany.’

‘He keeps that blouse with the wings and stuff in his suitcase. He tells his girls they have to be nice to him, he might never come back from the next one.’ He laughed.

Victoria laughed too, but it was unconvincing laughter. She held Jamie very tight and wondered what it would be like enduring the strain of knowing that Jamie might not come back. Why wasn’t Jamie a PRO, or someone else who didn’t have to risk his life?

‘Did you see Earl Koenige?’ asked Jamie. ‘Straw-haired kid with a you-all accent and big incredulous eyes?’

‘The one you’re going to be flying with? He looks no more than sixteen.’

‘He can handle his ship pretty well,’ said Jamie. It was not the sort of compliment he gave freely. ‘But he fell off the piano just after you left. He was trying to tap-dance and wave the Stars and Bars at the same time.’