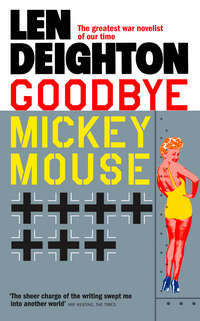

Goodbye Mickey Mouse

‘Did he hurt himself? He looked drunk.’

‘I don’t think Earl’s ever tasted whisky before. His folks are teetotal, church-going farmers. No, he bounced up okay and said he hoped he hadn’t hurt the piano.’

‘And did your friend Charlie arrive?’

‘He sent a message. His navigator had to stay on base, so the whole crew stayed with him. Say, do you have an aspirin?’

‘On the table under the light.’

He tore open the packet and swallowed two tablets without water. ‘I thought he’d cracked his skull at first, but Earl’s always falling off his bicycle or spilling hot coffee down himself. He writes to his folks every day and I guess without his accidents he’d have nothing to tell them.’

‘Well, he should have no lack of material for his next letter,’ said Victoria. ‘Was that really your Commanding Officer! He was playing dice with a sergeant, and calling him Harry, and passing a bottle of whisky back and forth. There were wads of five-pound notes changing hands on one roll of the dice.’

Jamie frowned. ‘The Colonel’s not an easy man to understand,’ he said. ‘Vince nearly ran afoul of him tonight.’

‘Vince?’

‘He was wearing that damned jacket when Colonel Dan got there. I thought we were heading for a real showdown. “What uniform are you wearing, Captain Madigan?” the old man said. Vince saluted smartly and said, “The one with the Christmas decorations, sir.” The Colonel smiled and took the drink Vince offered him. “If the provost marshal comes in here tonight, Madigan,” said Colonel Dan, “they’ll throw us both in the cooler.” Vince grinned and said, “That’s just the way I figured it, Colonel…” That Vince can talk his way out of anything. He told me he ran off with some married woman when he was still a kid in high school.’

‘Poor Vera.’

‘Poor Vera nothing! She was sitting on the stairs petting with MM after Vince took off.’

‘Is it the war that’s made us like this?’

‘Don’t be so female,’ said Jamie. ‘People grab a little happiness while there’s a chance. All I’m saying is, don’t let’s worry about Vera or Vince. Let them work out their own lives. Who knows when MM will buy the farm, who knows when I will.’

‘Buy the farm?’

‘Collect our government insurance.’

‘Don’t say things like that, I can’t bear the thought of anything happening to you!’ She buried her head under the bedclothes.

‘Come out of there, you crazy girl.’ He pulled the blanket down and admired her bare body. ‘Are you sure your parents won’t come back?’

Her head was under the pillow; she grunted a negative.

‘How can you be so sure?’

She threw off the pillow and turned over to laugh at his nervousness. ‘Because they’re with my grandparents in Scotland. They phoned this morning. You can relax.’

‘You didn’t want to go?’

‘We were working. My father said I shouldn’t ask for extra time off—the war comes first.’

‘Your father’s right,’ he said, caressing her. ‘Fathers are always right.’ She watched him. He hadn’t looked so tanned before, but now, compared with her own skin and the white sheets, he seemed like a bronze statue.

‘Was your father always right too?’ she asked.

‘I don’t know anything about my father,’ he replied.

‘I’m sorry.’

‘He’s not dead. My parents were divorced when I was only a kid. I stayed with my mother, and she got married again to a man named Farebrother. I guess a bridegroom gets a little tired of checking into a hotel and explaining why his kid has a different name.’

‘What’s your father’s name?’

‘Bohnen. Alexander Bohnen. His family came from Norway originally. They were boat-builders.’

‘Was your father one too?’

‘Not enough money in that, I guess.’ He was still staring at the ceiling. ‘Give me a cigarette, will you, sweetheart?’

‘You sound like Vince when you say “sweetheart”.’ She gave him the packet of cigarettes he’d put on the bedside table and the gold lighter that was balanced on top.

‘My father is an investment consultant in Washington DC. Or rather was. Now he’s become a full colonel—a chicken colonel they call them—in the Army Air Force. He went from civilian to colonel over night, and naturally he’s a staff officer, the difference between a staff officer and an investment consultant being largely sartorial.’

‘Naturally? I don’t know what an investment consultant does.’

‘I don’t either,’ Jamie admitted. ‘But I guess he tells people who need a million dollars where to get them cheaply.’

Victoria laughed. It was just another glimpse of this crazy American world. ‘He sounds like a man who works miracles.’

‘You took those words right out of my father’s mouth.’

‘You don’t like him?’

‘He’s tough and practical and successful. My father works twenty-four hours a day, drinking with the right people and dining with the right people. My mother had to play hostess in a town where entertaining is a highly competitive sport, and my father’s a harsh critic. He never married again—he didn’t need a wife, he needed a professional housekeeper.’

‘And your mother’s happy?’

‘She’s always been quiet and easygoing. My stepfather isn’t a genius, but he makes enough dough for them to sit in the sun a lot and take it easy. Santa Barbara is a great place for taking it easy.’ Jamie lit a cigarette. ‘My father should have been a politician. He’s a Mr Fixit. I guess he figured Uncle Sam would lose the war unless he got into uniform and told the Army what to do.’

‘Don’t you ever write to him?’

‘I get a monthly bulletin—mimeographed, but with my name inserted in his own handwriting—the same chatty little newsletter that he sends to all his important business contacts. That’s how I know he’s with the Air Force here in England.’

‘You never write back?’

He drew at his cigarette. ‘No, I never write back. You’re not going to start chewing me out already, are you?’

‘It is Christmas, Jamie. He’s your father, you could phone him.’

‘My father will not have noticed it’s Christmas.’ He’d only taken a couple of puffs at the cigarette, but he decided he didn’t want it any more and stubbed it out on the back of Victoria’s powder compact, tossing the stub into a flower vase. Victoria was appalled but decided not to ‘chew him out’. Instead, she leaned across and switched the light off again. When she’d snuggled down into the bedclothes he put his arm around her. ‘Okay,’ he said. ‘I’ll phone him in the morning.’

She cuddled closer to him and pretended to be asleep.

8 Colonel Alexander J. Bohnen

Even the Savoy Hotel’s youngest waiter could tell at a glance which men were Americans. They toyed with their food, holding forks in their right hands, and they distanced themselves from the table, turning their chairs sideways, and sometimes pulling back so they could sit with crossed legs. Only the British guests kept their knees under the table and addressed themselves wholeheartedly to the food.

Colonel Bohnen knew most of the men lunching in the private room that day, and even those he’d never met weren’t strangers, for he’d spent all his life with men like these—businessmen and civil servants and diplomats, even though so many of them now wore military or naval uniform. His white-haired companion was one of his closest friends. ‘If I live to be one hundred years old,’ Bohnen was telling him, ‘I’ll never equal the bang I got out of hearing my son’s voice on the phone.’

‘I’m glad he called, Alex.’

‘P-51s! He’s a captain assigned to the 220th Fighter Group. He’ll be flying fighter escort missions over Germany.’ Colonel Bohnen put his fork down and abandoned his meal.

‘You’ve arranged everything for him, no doubt,’ said the older man, with just a trace of mockery in his voice.

‘It’s my only son!’ said Bohnen defensively. ‘Certainly I had one of my assistants phone his commanding officer and mention that headquarters had a special interest in this newly assigned captain.’ Bohnen scratched his face. ‘He got a rather insubordinate response. To tell you the truth, I’m beginning to have misgivings about Jamie’s CO.’ His voice trailed away.

‘Don’t leave me in suspense, Alex.’

‘His Colonel’s efficiency rating is “excellent”; that’s the Army’s way of saying he stinks. His efficiency reports are larded with words such as “unorthodox” and “overconfident”, and “reckless”; fine and dandy for a young lieutenant who’s going places but not the kind of language I want applied to a colonel leading a Fighter Group.’

‘With your son in it, you mean. Is he an Academy man?’

Bohnen shook his head. ‘A West Pointer I could swallow, but this guy is a down-at-heel pilot who joined the Air Corps when barnstorming got too tough for him.’

‘Is this young Jamie’s opinion?’

Bohnen was alarmed. ‘My God, don’t let Jamie ever find out I’ve been checking up on his commander! You know how prim and proper Jamie always is.’

‘I’d never even recognize the boy after all this time. I haven’t seen Mollie for nearly three years.’

Bohnen frowned at the sound of his ex-wife’s name and tapped cigar ash. ‘Jamie was a gentle child, careful with his toys, considerate to his friends, and trusting his parents—too trusting, maybe. Mollie poisoned the boy’s mind against me. But as terrible as that sounds, I’ve never allowed myself to become bitter about it.’

‘Mollie’s father was a tough man to do business with. She gets it from him.’

‘He inherited a going concern,’ said Bohnen. ‘What did old Tom have to be so tough about? He inherited a fortune and poured it down the drain. He died nearly penniless, I’ve heard. His grandfather must be turning in his grave. Look at any picture book of America’s history and you’ll find a Washbrook harvesting machine or tractor. When old Tom Washbrook gave me permission to marry his daughter, I was walking on air. I loved Mollie dearly and I was sure I could make her father see what had to be done to save the factories, but he would never listen to me—I was too young to give him advice. Sometimes I think he deliberately did the opposite of anything I suggested. And Mollie gave me no support, she always sided with Tom. He has a right to make his own mistakes, she liked to tell me.’

‘Mollie loved her father, Alex. You know that. She doted on him.’

‘She watched him run that giant corporation right into the ground. What kind of love is that?’

‘So you never hear from Mollie?’

‘Mollie is a one-man woman, always was and always will be, I guess. Once she’d turned her back on me she didn’t want to even think about me again. A clean break she said she wanted, and I went along with that, even when it meant losing my son. I knew someday he’d find his way back to me and I thank the good Lord that he chose this Christmas to do His will.’

Bohnen’s companion looked at his watch. ‘I wish I could hang on here and see the boy again, Alex.’

‘He tells me he’s met a wonderful girl,’ said Bohnen, ‘and he’s giving me the chance to meet her.’

‘The British trains are all to hell, Alex. Does he have to come far?’

‘I sent a car,’ said Bohnen.

The other man smiled. ‘I’m glad to see you’re not letting the war cramp your style, Alex. Do you think I should get myself a khaki suit?’

‘Running an air force is no different from running a corporation,’ Bohnen told him solemnly. ‘The fact is, running an air force in wartime is easier than running a corporation. As I told my boss, the opportunity to threaten a few vice-presidents with a firing squad would have done wonders for Boeing and Lockheed when they were having their troubles.’

‘You can say that again, Alex!’

‘And what about that damned airline you sank so much good money into? A few executions in that boardroom would have worked wonders.’

‘Military life obviously suits you.’

‘It’s fascinating,’ said Bohnen. ‘And it’s a big job. There are now more US soldiers in these islands than British ones! And our planes outnumber the RAF by about four thousand!’

‘What’s the next step, Alex, Buckingham Palace?’

‘Think big,’ Bohnen said, and laughed.

‘Must go.’ He looked round the room and then back at Bohnen. ‘Who is hosting this feast?’

‘Brett Vance. You know Brett—made a fortune out of cocoa futures just before the war…the big gorilla with glasses, over there in the corner, tearing blooms out of the flower arrangement. No need to overdo the grateful thanks. He just persuaded the Army to put his candy bars on sale at every PX in the European Theatre.’

‘Nice work, Brett Vance!’ said the old man sardonically.

‘Can you imagine how many candy bars those soldiers will consume? Countless divisions of fit young men, hiking and digging and so on, night and day in all kinds of weather.’

‘Does that mean you’re buying stocks in candy bars?’

Bohnen looked shocked. ‘You know me better than that. Let others play the market if they want, but while I’m in the Army there’s no way I could be a party to that kind of thing.’ He saw his companion smiling and wondered if he was being tested.

‘You’re becoming a kind of paragon, Alex. I think maybe I prefer that wheeler-dealer I used to know back home.’

‘I missed the first war. I feel I owe something to Uncle Sam, and I’m going to give this job all I’ve got.’

The older man could think of no response to Bohnen’s passionate declaration. From the other end of the room there was laughter as guests took their leave. ‘Give my love to Jamie. I look forward to hearing your opinion of his girl.’

‘Jamie’s too young to marry,’ said Bohnen.

‘And how about his CO—are you going to let him get married?’

‘Very funny,’ said Bohnen. ‘I suppose you think I interfere too much.’

‘Let the boy live his own life, Alex.’

‘See you next week,’ said Bohnen. ‘You could take a couple of messages for people in Washington.’

‘Go easy on the boy, Alex. Jamie doesn’t have that hard cutting edge that we grew back in 1929.’

‘He’ll get no preferred treatment. He’s a soldier, and this is war.’

‘It’s serious, Dad. We’re in love.’ He found it difficult to talk to his father after so many years apart.

‘And when exactly do I get a chance to meet the young lady?’ Colonel Bohnen consulted his watch.

‘Three fifteen. She thought we’d like to have some time together. She’s downstairs right now, having lunch with her aunt.’

‘That’s most considerate of her,’ Bohnen said, and wondered whether it was intended as an opportunity for Jamie to get his blessing for an intended marriage.

‘You’ll like her, Dad. It was her idea that I phone you.’

How like Mollie the boy looked, the same mouth and same wide-open earnest eyes and the same nervous manner, as if he expected Alex Bohnen to bite his head off. What did the boy expect—a paternal chat about the unhappiness that can follow a hasty marriage? Or the senior officer lecture about the socio-medical consequences of casual relationships? He would get neither. ‘Sure, I’m going to like her,’ said Bohnen, pouring more of the Château Margaux. ‘Eat the lamb chops before your meal gets cold.’ Jamie had let his father choose the food and wine, knowing how much pleasure that would give him. He was right; Bohnen had been through the room-service menu with meticulous care and questioned the waiter at length about the temperature of the wine and the locality in which the lamb had been reared.

‘It’s a fine meal,’ said Jamie.

‘It’s better to have it served up here in my suite. I would have eaten with you but I had an official lunch.’

‘It’s a fine claret too.’ Bohnen noted his son’s Britishism and wondered if he’d been tutored by old Tom Washbrook, who kept a legendary table, or by his no-good brother-in-law who was drinking away the profits of the bar and grill he owned in Perth Amboy.

‘The Savoy cellars go on forever. This is the finest hotel in the world, Jamie. And the management know me from way back before the war.’

‘1934,’ said Jamie, turning the bottle to examine the label. ‘So you’re still very busy?’

‘We’re in the middle of the biggest expansion programme in history, and now Doolittle has arrived to take over from General Eaker.’

‘What’s the story behind that one?’

‘Go back to last October and read about the Schweinfurt raid, the way I’ve been doing to prepare a confidential report. It was a long ride through clear skies, our bombers punished all the way there and all the way back again. No escorting fighters, and the Germans had plenty of time to land and refuel before slaughtering more of our boys. Twenty-eight bombers were lost on the outward leg, and by the time formations reached the target, thirty-four had turned back with battle damage or mechanical failure. The return trip was even worse!’

‘I’m listening, Dad.’

Bohnen looked at his son. He didn’t want to frighten him, but he knew that a son of his would not be readily frightened. ‘If the truth of it ever gets out, Congress will tear the high command to pieces. Any chance of America getting a separate air force will have gone for good. Even now we’re not publishing the whole truth. We don’t tell anyone about our ships that crash into the ocean on the way back, or the ones that land with dead and injured crew. We don’t say that for every three men wounded in battle there are four crewmen hospitalized with frostbite. And we don’t tell anyone how many bombers are junked because they’re beyond economical repair. We don’t talk about the men who would rather face a court martial than go back into combat, or about the psychiatric cases we dope up and send home. We don’t let reporters go to the bases where we’re having trouble with morale, or admit to the decisions we’ve had to make about not sending unescorted formations back to those tough targets again.’

‘It sounds bad.’

‘We never released the true Schweinfurt story and my guess is we never will.’

‘With the Mustangs we’ll escort them all the way.’ Jamie had forgotten how intense his father always became about his work. He wished he could see him relax, but he never did.

‘I spent last month pleading for long-range gas tanks. We’re using British compressed-paper ones, we can’t get enough. Then on Friday I got a long report from Washington telling me it’s impossible to make drop tanks from paper. That’s what we’re up against, Jamie, the bureaucratic mind.’

‘The Mustang is the most beautiful ship I ever flew.’

‘And everyone knew it last year except the “experts” at Materiel Division who seemed to resent the fact that she needed a British-designed engine to make her into a real winner. The Air Force lost months due to those arguments, and all the time the bomber crews paid in blood.’

‘Will things be better under Doolittle?’

‘New machines, new ideas, new commander. I sure hope he’ll get tough with the British. That’s the most urgent thing at present.’

‘The British?’

‘Churchill wants us to fly at night on account of the casualties we’re suffering.’

‘Doesn’t night bombing just mean area bombing—just tossing bombs into the centre of big towns? There’s no industrial plant in town centres, so how could his policy ever end the war?’

‘Night raiding would mean taking more advice and equipment from the RAF. First we take advice from them, then lessons, and eventually we’ll be taking orders.’

‘But Eisenhower’s been appointed Supreme Commander of the Anglo-American invasion forces.’

‘It sounds pally,’ said Bohnen. ‘It sounds like the British are resigned to taking orders from us. But wait until they announce the name of Ike’s deputy, and he’ll be a Britisher. It’s one more step in the British plan to absorb us into RAF Bomber Command. Churchill is using the slogan “round-the-clock bombing” and is suggesting that we coordinate it under one commander. Get the picture? Only one commander for the Army, so only one commander for the Allied bombing force. And who’s the most experienced man for that job? Arthur Harris. If we squawk, the British are going to remind us that Eisenhower’s got the top job. And that’s the way it’s going, the British will get all the powerful executive jobs while reminding us that they’re serving under Eisenhower.’

Jamie was sorting through his vegetables to set aside tiny pieces of onion that he wouldn’t eat. Bohnen remembered him doing the same thing when he was a tiny child; they’d often had words about it. Fastidiously Jamie wiped his mouth on his napkin and took another sip of wine. ‘The British are good at politicking, are they?’

‘They excel at it. Montgomery can pick up his phone and talk with Churchill whenever he feels like it. Bert Harris—chief of RAF Bomber Command—has Churchill over for dinner and shows him picture books of what the RAF have done to Germany. Can you imagine Eaker, Doolittle, or even General Arnold having the chance to chat personally with the President? The way it stands now, Montgomery, via Churchill, has more influence with Roosevelt than our own chiefs of staff have.’ Bohnen drank a little of the Château Margaux and paused long enough to relish the aftertaste. ‘1928 was the great one, but this ’34 Margaux is a close contender. One day I’ll retire and devote the rest of my life to comparing the ’28s and ’29s.’

‘I guess we’ve got to keep hitting strategic targets,’ said Jamie quietly. He hadn’t wanted to get into this high-level argument that his father so obviously relished.

Bohnen shook his head. ‘We’re going after the Luftwaffe, Jamie. There’s no alternative. There’s not much time before we invade the mainland—we have to have undisputed air superiority over those beaches. General Arnold’s New Year orders will make it public record: destroy German planes in the air, on the ground, and while they’re still on the production lines. It’s going to be tough, damned tough.’

‘Don’t worry about me, Dad.’

‘I won’t worry,’ said Bohnen. His son looked so vulnerable he wanted to grab him and hug him as he used to when he was small. He almost reached across the table to take his hand, but fathers don’t do that to their grown-up fighter pilot sons. In some ways mothers are lucky.

Victoria arrived on time, and Bohnen was surprised by the tall, dark confident girl who greeted him. She was obviously well bred, with all those old-fashioned virtues he’d seen in Jamie’s mother so long ago.

‘You have a suite on the river, Colonel. You’re obviously a man of influence.’

‘How I wish I were, Miss Cooper.’

‘Charm, then, Colonel Bohnen.’

‘I’m not even a real colonel, just a dressed-up civilian. I’m a phony, Miss Cooper. Not one of your gilt or electroplated ones either. I’m a phony all the way through.’

She laughed softly. Bohnen had always said that a woman, even more than a man, will reveal everything you need to know about her by her laugh—not just by the things she’ll laugh at, or the time chosen for it, but by the sound. Victoria Cooper laughed beautifully, a gracious but genuine sound that came from the heart rather than from the belly.

‘You look too young to be Jamie’s father,’ she said.

‘Who could argue against a compliment like that?’ said Bohnen.

She went across to the table where Jamie was finishing his meal, and they kissed decorously.

‘Can I order some tea or coffee for you, Miss Cooper?’

‘Please call me Victoria. No, I’ll steal some of Jamie’s wine.’ Jamie watched the two of them; already they seemed to know each other well enough to spar in a way Jamie had never done before.

Bohnen brought another wineglass from his liquor cabinet. ‘Jamie tells me his mother is English,’ said Victoria.

‘Mollie likes to say that. The truth is, she arrived a little earlier than the doctor anticipated and her parents were in England. Tom was setting up a tractor plant near Bradford. Mollie was born in a grand house in Wharfedale, Yorkshire, delivered by the village midwife, so the story goes, with old Tom boiling up kettles of water and only an oil lamp to light the room.’