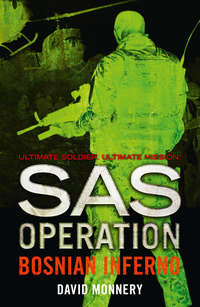

Bosnian Inferno

Docherty placed his pint down carefully and waited for Davies to continue.

‘This is what we think happened,’ the CO began. ‘Reeve and his wife seem to have hit a bad patch while he was working in Zimbabwe. Or maybe it was just a break-up waiting to happen,’ he added, with all the feeling of someone who had shared the experience. ‘Whatever. She left him there and headed back to where she came from, which, as you know, was Yugoslavia. How did they meet – do you know?’

‘In Germany,’ Docherty said. ‘Nena was a guest-worker in Osnabrück, where Reeve was stationed. She was working as a nurse while she trained to be a doctor.’ He could see her in his mind’s eye, a tall blonde with high Slavic cheekbones and cornflower-blue eyes. Her family was nominally Muslim, but as for many Bosnians it was more a matter of culture than religion. She had never professed any faith in Docherty’s hearing.

He felt saddened by the news that they had split up. ‘Did she take the children with her?’ he asked.

‘Yes. To the small town where she grew up. Place called Zavik. It’s up in the mountains a long way from anywhere.’

‘Her parents still lived there, last I knew.’

‘Ah. Well all this was just before the shit hit the fan in Bosnia, and you can imagine what Reeve must have thought. I don’t know what Zimbabwean TV’s like, but I imagine those pictures were pretty hard to escape last spring wherever you were in the world. Maybe not. For all we know he was already on his way. He seems to have arrived early in April, but this is where our information peters out. We think Nena Reeve used the opportunity of his visit to Zavik to make one of her own to Sarajevo, either because he could babysit the children or just as a way of avoiding him – who knows? Either way she chose the wrong time. All hell broke loose in Sarajevo and the Serbs started lobbing artillery shells at anything that moved and their snipers started picking off children playing football in the street. And she either couldn’t get out or didn’t want to…’

‘Doctors must be pretty thin on the ground in Sarajevo,’ Docherty thought out loud.

Davies grunted his agreement. ‘As far as we know, she’s still there. But Reeve – well, this is mostly guesswork. We got a letter from him early in June, explaining why he’d not returned to Zimbabwe, and that as long as he feared for the safety of his children he’d stay in Zavik…’

‘I never heard anything about it,’ Docherty said.

‘No one did,’ Davies said. ‘An SAS soldier on the active list stuck in the middle of Bosnia wasn’t something we wanted to advertise. For any number of reasons, his own safety included. Anyway, it seems that the town wasn’t as safe as Reeve’s wife had thought, and sometime in July it found itself with some unwelcome visitors – a large group of Serbian irregulars. We’ve no idea what happened, but we do know that the Serbs were sent packing…’

‘You think Reeve helped organize a defence?’

Davies shrugged. ‘It would hardly be out of character, would it? But we don’t know. All we have since then is six months of silence, followed by two months of rumours.’

‘Rumours of what?’

‘Atrocities of one kind and another.’

‘Reeve? I don’t believe it.’

‘Neither do I, but…We’re guessing that Reeve – or someone else with the same sort of skills – managed to turn Zavik into a town that was too well defended to be worth attacking. Which would work fine until the winter came, when the town would start running short of food and fuel and God knows what else, and either have to freeze and starve or take the offensive and go after what it needed. And that’s what seems to have happened. They’ve been absolutely even-handed: they’ve stolen from everyone – Muslims, Serbs and Croats. And since none of these groups, with the partial exception of the Muslims, likes admitting that somewhere there’s a town in which all three groups are fighting alongside each other against the tribal armies, you can guess who they’re all choosing to concentrate their anger against.’

‘Us?’

‘In a nutshell. According to the Serbs and the Croats there’s this renegade Englishman holed up in central Bosnia like Marlon Brando in Apocalypse Now, launching raids against anyone and everyone, delighting in slaughter and madness, and probably waiting to mutter “the horror, the horror” to the man who arrives intent on terminating him with extreme prejudice.’

‘I take it our political masters are embarrassed,’ Docherty said drily.

‘Not only that – they’re angry. They like touting the Regiment as an example of British excellence, and since the cold war ended they’ve begun to home in on the idea of selling our troops as mercenaries to the UN. All for a good cause, of course, and what the hell else do we have to sell any more? The Army top brass are all for it – it’s their only real argument for keeping the sort of resource allocations they’re used to. Finding out that one of their élite soldiers is running riot in the middle of the media’s War of the Moment is not their idea of good advertising.’

Docherty smiled grimly. ‘Surprise, surprise,’ he said, and emptied his glass. He could see now where this conversation was leading. ‘Same again?’ he asked.

‘Thanks.’

Docherty gave his order to the barman and stood there thinking about John Reeve. They’d known each other almost twenty years, since they’d been thrown into the deep end together in Oman. Reeve had been pretty wild back then, and he hadn’t noticeably calmed down with age, but Docherty had thought that if anyone could turn down the fire without extinguishing it altogether then Nena was the one.

What would Isabel say about his going to Bosnia? he asked himself. She’d probably shoot him herself.

Back at the booth he asked Davies the obvious question: ‘What do you want me to do?’

‘I have no right to ask you to do anything,’ Davies answered. ‘You’re no longer a member of the Regiment, and you’ve already done more than your bit.’

‘Aye,’ Docherty agreed, ‘but what do you want me to do?’

‘Someone has to get into Zavik and talk Reeve into getting out. I don’t imagine either is going to be easy, but he’s more likely to listen to you than anyone else.’

‘Maybe.’ Reeve had never been very good at listening to anyone, at least until Nena came along. ‘How would I get to Zavik?’ he asked. ‘And where is it, come to that?’

‘About fifty miles west of Sarajevo. But we haven’t even thought about access yet. We can start thinking about the hows if and when you decide…’

‘If you should choose to accept this mission…’ Docherty quoted ironically.

‘…the tape will self-destruct in ten seconds,’ Davies completed for him. Clearly both men had wasted their youth watching crap like Mission Impossible.

‘I’ll need to talk with my wife,’ Docherty said. ‘What sort of time-frame are we talking about?’ It occurred to him, absurdly, that he was willing to go and risk his life in Bosnia, but only if he could first enjoy this Christmas with his family.

‘It’s not a day-on-day situation,’ Davies said. ‘Not as far as we know, anyway. But we want to send a team out early next week.’

‘The condemned men ate a hearty Christmas dinner,’ Docherty murmured.

‘I hope not,’ Davies said. ‘This is not a suicide mission. If it looks like you can’t get to Zavik, you can’t. I’m not sacrificing good men just to put a smile on the faces of the Army’s accountants.’

‘Who dares wins,’ Docherty said with a smile.

‘That’s probably what they told Icarus,’ Davies observed.

‘Don’t you want me to go?’ Docherty asked, only half-seriously.

‘To be completely honest,’ Davies said, ‘I don’t know. Have you been following what’s happening in Bosnia?’

‘Not as much as I should have. My wife probably knows more about it than I do.’

‘It’s a nightmare,’ Davies said, ‘and I’m not using the word loosely. All the intelligence we’re getting tells us that humans are doing things to each other in Bosnia that haven’t been seen in Europe since the religious wars of the seventeenth century, with the possible exception of the Russian Front in the last war. We’re talking about mass shootings, whole villages herded into churches and burnt alive, rape on a scale so widespread that it must be a coordinated policy, torture and mutilation for no other reason than pleasure, war without any moral or human restraint…’

‘A heart of darkness,’ Docherty murmured, and felt a shiver run down his spine, sitting there in his favourite pub, in the city of his birth.

After giving Davies a lift to his hotel Docherty drove slowly home, thinking about what the CO had told him. Part of him wanted to go, part of him wasn’t so sure. Did he feel the tug of loyalty, or was his brain just using that as a cover for the tug of adventure? And in any case, didn’t his wife and children have first claim on his loyalty now? He wasn’t even in the Army any more.

She was watching Newsnight on TV, already in her dressing-gown, a glass of wine in her hand. The anxiety seemed to have left her eyes, but there was a hint of coldness there instead, as if she was already protecting herself against his desertion.

Ironically, the item she was watching concerned the war in Bosnia, and the refugee problem which had developed as a result. An immaculately groomed Conservative minister was explaining how, alas, Britain had no more room for these tragic victims. After all, the UK had already taken more than Liechtenstein. Docherty wished he could use the Enterprise’s transporter system to beam the bastard into the middle of Tuzla, or Srebenica, or wherever it was this week that he had the best chance of being shredded by reality.

He poured himself what remained of the wine, and found Isabel’s dark eyes boring into him. ‘Well?’ she asked. ‘What did he want?’

‘He wants me to go and collect John Reeve from there,’ he said, gesturing at the screen.

‘But they’re in Zimbabwe…’

‘Not any more.’ He told her the story that Davies had told him.

When he was finished she examined the bottom of her glass for a few seconds, then lifted her eyes to his. ‘They just want you to go and talk to him?’

‘They want to know what’s really happening.’

‘What do they expect you to say to him?’

‘They don’t know. That will depend on whatever it is he’s doing out there.’

She thought about that for a moment. ‘But he’s your friend,’ she said, ‘your comrade. Don’t you trust him? Don’t you believe that, whatever he’s doing, he has a good reason for doing it.’

It was Docherty’s turn to consider. ‘No,’ he said eventually. ‘I didn’t become his friend because I thought he had flawless judgement. If I agree with whatever it is he’s doing, I shall say so. To him and Barney Davies. And if I don’t, the same applies.’

‘Are they sending you in alone?’

‘I don’t know. And that’s if I agree to go.’

‘You mean, once I give you my blessing.’

‘No, no, I don’t. That’s not what I mean at all. I’m out of the Army, out of the Regiment. I can choose.’

There was both amusement and sadness in her smile. ‘They’ve still got you for this one,’ she said. ‘Duty and loyalty to a friend would have been enough in any case, but they’ve even given you a mystery to solve.’

He smiled ruefully back at her.

She got up and came to sit beside him on the sofa. He put an arm round her shoulder and pulled her in. ‘If it wasn’t for the niños I’d come with you,’ she said. ‘You’ll probably need someone good to watch your back.’

‘I’ll find someone,’ he said, kissing her on the forehead. For a minute or more they sat there in silence.

‘How dangerous will it be?’ she asked at last.

He shrugged. ‘I’m not sure there’s any way of knowing before we get there. There are UN troops there now, but I don’t know where in relation to where Reeve is. The fact that it’s winter will help – there won’t be as many amateur psychopaths running around if the snow’s six feet deep. But a war zone is a war zone. It won’t be a picnic.’

‘Who dares had better damn well come home,’ she said.

‘I will,’ he said softly.

2

Nena Reeve pressed the spoon down on the tea-bag, trying to drain from it what little strength remained without bursting it. She wondered what they were drinking in Zavik. Probably melted snow.

Her holdall was packed and ready to go, sitting on the narrow bed. The room, one of many which had been abandoned in the old nurses’ dormitory, was about six feet by eight, with one small window. It was hardly a generous space for living, but since Nena usually arrived back from the hospital with nothing more than sleep in mind, this didn’t greatly concern her.

Through the window she had a view across the roofs below and the slopes rising up on the other side of the Miljacka valley. In the square to the right there had once been a mosque surrounded by acacias, its slim minaret reaching hopefully towards heaven, but citizens hungry for fuel had taken the trees and a Serbian shell had cut the graceful tower in half.

There was a rap on the door, and Nena walked across to let in her friend Hajrija Mejra.

‘Ready?’ Hajrija asked, flopping down on the bed. She was wearing a thick, somewhat worn coat over camouflage fatigue trousers, army boots and a green woollen scarf. Her long, black hair was bundled up beneath a black woolly cap, but strands were escaping on all sides. Hajrija’s face, which Nena had always thought so beautiful, looked as gaunt as her own these days: the dark eyes were sunken, the high cheekbones sharp enough to cast deep shadows.

Well, Hajrija was still in her twenties. There was nothing wrong with either of them that less stress and more food wouldn’t put right. The miracle wasn’t how ill they looked – it was how the city’s 300,000 people were still coping at all.

She put on her own coat, hoping that two sweaters, thermal long johns and jeans would be warm enough, and picked up the bag. ‘I’m ready,’ she said reluctantly.

Hajrija pulled herself upright, took a deep breath and stood up. ‘I don’t suppose there’s any point in trying to persuade you not to go?’

‘None,’ Nena said, holding the door open for her friend.

‘Tell me again what this Englishman said to you,’ Hajrija said as they descended the first flight of stairs. The lift had been out of operation for months. ‘He came to the hospital, right?’

‘Yes. He didn’t say much…’

‘Did he tell you his name?’

‘Yes. Thornton, I think. He said he came from the British Consulate…’

‘I didn’t know there was a British Consulate.’

‘There isn’t – I checked.’

‘So where did he come from?’

‘Who knows? He didn’t tell me anything, he just asked questions about John and what I knew about what was happening in Zavik. I said, “Nothing. What is happening in Zavik?” He said that’s what he wanted to know. It was like a conversation in one of those Hungarian movies. You know, two peasants swapping cryptic comments in the middle of an endless cornfield…’

‘Only you weren’t in a cornfield.’

‘No, I was trying to deal with about a dozen bullet and shrapnel wounds.’

They reached the bottom of the stairs and cautiously approached the doors. It had only been light for about half an hour, and the Serb snipers in the high-rise buildings across the river were probably deep in drunken sleep, but there was no point in taking chances. The fifty yards of open ground between the dormitory doors and the shelter of the old medieval walls was the most dangerous stretch of their journey. Over the last six months more than a dozen people had been shot attempting it, three fatally.

‘Ready?’ Hajrija asked.

‘I guess.’

The two women flung themselves through the door and ran as fast as they could, zigzagging across the open space. Burdened down by the holdall, Nena was soon behind, and she could feel her stomach clenching with the tension, her body braced for the bullet. Thirty metres more, twenty metres, ten…

She sank into the old Ottoman stone, gasping for breath.

‘You’re out of shape,’ Hajrija said, only half-joking.

‘Whole bloody world’s out of shape,’ Nena said. ‘Let’s get going.’

They walked along the narrow street, confident that they were hidden from snipers’ eyes. There was no one about, and the silence seemed eerily complete. Usually by this time the first shells of the daily bombardment had landed.

It was amazing how they had all got used to the bombardment, Nena thought. Was it a tribute to human resilience, or just a stubborn refusal to face up to reality? Probably a bit of both. She remembered the queue in front of the Orthodox Cathedral when the first food supplies had come in by air. A sniper had cut down one of the people in the line, but only a few people had run for cover. There were probably a thousand people in the queue, and like participants in a dangerous sport each was prepared to accept the odds against being the next victim. Such a deadening of the nerve-ends brought a chill to her spine, but she understood it well enough. How many times had she made that sprint from the dormitory doors? A hundred? Two hundred?

‘Even if you’re right,’ Hajrija said, ‘even if Reeve has got himself involved somehow, I don’t see how you can help by rushing out there. You do know how unsafe it is, don’t you? There’s no guarantee you’ll even get there…’

Nena stopped in mid-stride. ‘Please, Rija,’ she said, ‘don’t make it any more difficult. I’m already scared enough, not to mention full of guilt for leaving the hospital in the lurch. But if Reeve is playing the local warlord while he’s supposed to be looking after the children, then…’ She shook her head violently. ‘I have to find out.’

‘Then let me come with you. At least you’ll have some protection.’

‘No, your place is here.’

‘But…’

‘No argument.’

Sometimes Nena still found it hard to believe that her friend, who six months before had been a journalism student paying her way through college as a part-time nurse, was now a valued member of an élite anti-sniper unit. Someone who had killed several men, and yet still seemed the same person she had always been. Sometimes Nena worried that there was no way Hajrija had not been changed by the experiences, and that it would be healthier if these changes showed on the surface, but at others she simply put it down to the madness that was all around them both. Maybe the fact that they were all going through this utter craziness would be their salvation.

Maybe they had all gone to hell, but no one had bothered to make it official.

‘I’ll be all right,’ she said.

Hajrija looked at her with exasperated eyes.

‘Well, if I’m not, I certainly don’t want to know I’ve dragged you down with me.’

‘I know.’

They continued on down the Marsala Tita, sprinting across two dangerously open intersections. There were more people on the street now, all of them keeping as close to the buildings as possible, all with skin stretched tight across the bones of their scarf-enfolded faces.

It was almost eight when they reached the Holiday Inn, wending their way swiftly through the Muslim gun emplacements in and around the old forecourt. The hotel itself looked like Beirut on a bad day, its walls pock-marked with bullet holes and cratered by mortar shells. Most of its windows had long since been broken, but it was still accommodating guests, albeit a restricted clientele of foreign journalists and ominous-looking ‘military delegations’.

‘He’s not here yet,’ Hajrija said, looking round the lobby.

Nena followed her friend’s gaze, and noticed an AK47 resting symbolically on the receptionist’s desk.

‘Here he is,’ Hajrija said, and Nena turned to see a handsome young American walking towards them. Dwight Bailey was a journalist, and several weeks earlier he had followed the well-beaten path to Hajrija’s unit in search of a story. She was not the only woman involved in such activities, but she was probably, Nena guessed, one of the more photogenic. Bailey had not been the first to request follow-up interviews in a more intimate atmosphere. Like his bed at the Holiday Inn, for example. So far, or at least as far as Nena knew, Hajrija had resisted any temptation.

Bailey offered the two women a boyish smile full of perfect American teeth, and asked Hajrija about the other members of her unit. He seemed genuinely interested in how they were, Nena thought. If age made all journalists cynical, he was still young.

And somewhat hyperactive. ‘Dmitri’s late,’ he announced, hopping from one foot to the other. ‘He and Viktor are our bodyguards,’ he told Nena. ‘Russian journalists. Good guys. The Serbs don’t mess with the Russians if they can help it,’ he explained. ‘The Russians are about the only friends they have left.’

He said this with absolute seriousness, as if he could hardly believe it.

‘Hey, here they are,’ he called out as the two Russians came into view on the stairs. Both men had classically flat Russian faces beneath the fur hats; both were either bear-shaped or wearing enough undergarments to survive a cold day in Siberia. In fact the only obvious way of distinguishing one from the other was by their eyebrows: Viktor’s were fair and almost invisible, Dmitri’s bushy and black enough for him to enter a Brezhnev-lookalike contest. Both seemed highly affable, as if they’d drunk half a pint of vodka for breakfast.

The two women embraced each other. ‘Be careful,’ Hajrija insisted. ‘And don’t take any risks. And come back as soon as you can.’ She turned to the American. ‘And you take care of my friend,’ she ordered him.

He tipped his head and bowed.

The four travellers threaded their way out through the hotel’s kitchens to where a black Toyota was parked out of sight of snipers. The two Russians climbed into the front, and Nena and Bailey into the back.

Two distant explosions, one following closely on the other, signalled the beginning of the daily bombardment. The shells had fallen at least two kilometres away, Nena judged, but that didn’t mean the next ones wouldn’t fall on the Toyota’s roof.

Viktor started up the car and pulled it out of the car park, accelerating all the while. The most dangerous stretch of road ran between the Holiday Inn and the airport, and they were doing more than sixty miles per hour by the time the car hit open ground. Viktor had obviously passed this way more than once, for as he zigzagged wildly to and fro, past the burnt-out hulks of previous failed attempts, he was casually lighting up an evil-smelling cigarette from the dashboard lighter.

Nena resisted the temptation to squeeze herself down into the space behind the driver’s seat, and was rewarded with a glimpse of an old woman searching for dandelion leaves in the partially snow-covered verge, oblivious to their car as it hurtled past.

Thirty seconds later and they were through ‘Murder Mile’, and slowing for the first in a series of checkpoints. This one was manned by Bosnian police, who waved them through without even bothering to examine the three men’s journalistic accreditation. Half a mile further, they were waved down by a Serb unit on the outskirts of Ilidza, a Serb-held suburb. The men here wore uniforms identifying them as members of the Yugoslav National Army. They were courteous almost to a fault.

‘Hard to believe they come from Mordor,’ Bailey said with a grin.

It was, Nena thought. Sometimes it was just too easy to think all Serbs were monsters, to forget that there were still 80,000 of them in Sarajevo, undergoing much the same hardships and traumas as everyone else. And then it became hard to understand how the men on the hills above Sarajevo could deliberately target their big guns on the hospitals below, and how the snipers in the burnt-out tower blocks could deliberately blow away children barely old enough to start school.

They passed safely through another Serb checkpoint and, as the two Russians pumped Bailey about their chances of emigration to the USA, the road ran up out of the valley, the railway track climbing to its left, the rushing river falling back towards the city on its right. Stretches of dark conifers alternated with broad swathes of snow-blanketed moorland as they crested a pass and followed the sweeping curves of the road down into Sanjic. Here a minaret still rose above the roofs of the small town nestling in its valley, and as they drove through its streets Nena could see that the Christian churches had not paid the price for the mosque’s survival. Sanjic had somehow escaped the war, at least for the moment. She hoped Zavik had fared as well.