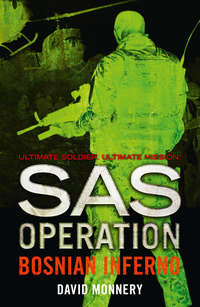

Bosnian Inferno

‘This must have been what all of Bosnia was like before the war,’ Bailey said beside her. There was a genuine sadness in his voice which made her wonder if she had underestimated him.

‘How long have you been here?’ she asked.

‘I came in early November,’ he said.

‘Who do you work for?’

‘No one specific. I’m a freelance.’

She looked out of the window. ‘If you get the chance,’ she said, ‘and if this war ever ends, you should come in the spring, when the trees are in blossom. It can look like an enchanted land at that time of year.’

‘I’d love to,’ he said. ‘I…I thought I knew quite a lot of the world before I came here,’ he said. ‘I’ve been all over Europe, all over the States of course, to Australia and Singapore…But I feel like I’ve never been anywhere like this. And I don’t mean the war,’ he said hurriedly, ‘though maybe that’s what makes everything more vivid. I don’t know…’

She smiled at him, and felt almost like patting his hand.

The road was climbing again now, a range of snow-covered mountains looming on their left. She remembered the trip across the mountains to Umtali while they were in Africa. The children had been bored in the back seat and she’d been short-tempered with them. Reeve, though, had for once been an exemplary father, painstakingly prising them out of their sulk. But he’d always been a good father, much to her surprise. She’d expected a great husband and a poor father, and ended up with the opposite.

No, that was harsh.

She wondered again what she would find in Zavik, always assuming she got there. The three journalists were only taking her as far as Bugojno, and from there she would probably still have a problem making it up into the mountains. The roads might be open, might be closed – at this time of the year the chances were about fifty-fifty.

The car began slowing down and she looked up to see a block on the road ahead. A tractor and a car had been positioned nose to nose at an angle, and beside them four men were standing waiting. Two of them were wearing broad-brimmed hats. ‘Chetniks,’ one of the Russians said, and she could see the straggling beards sported by three of the four. The other man, it soon became clear, wasn’t old enough to grow one.

From the first moment Nena had a bad feeling about the situation. The Russians’ bonhomie was ignored, their papers checked with a mixture of insolence and sarcasm by the tall Serb who seemed to be in charge. ‘Don’t you think Yeltsin is a useless wanker?’ he asked Viktor, who agreed vociferously with him, and said that in his opinion Russia could declare itself in favour of a Greater Serbia. The Chetnik just laughed at him, and moved on to Bailey. ‘You like Guns ’N’ Roses?’ he asked him in English.

‘Who?’ Bailey asked.

‘Rock ’n’ roll,’ the Chetnik said. ‘American.’

‘Sorry,’ Bailey said.

‘It’s OK,’ the Chetnik said magnanimously, and looked at Nena. His pupils seemed dilated, probably by drugs of some kind or another. ‘Leave the woman behind,’ he told the Russians in Serbo-Croat.

The Russians started arguing – not, Nena thought, with any great conviction.

‘What’s going on?’ Bailey wanted to know.

She told him.

‘But they can’t do that!’ he exclaimed, and before Nena could stop him he was opening the door and climbing out on to the road. ‘Look…’ he started to say, and the Chetnik’s machine pistol cracked. The American slid back into Nena’s view, a gaping hole where an eye had been.

The Russians in the front seat seemed suddenly frozen into statues.

‘We just want the woman,’ the Chetnik was telling them.

Viktor turned round to face her, his eyes wide with fear. ‘I think…’

She shifted across the back seat and climbed out of the same door the American had used. She started bending down to examine him, but was yanked away by one of the Chetniks. The leader grabbed the dead man by the feet and unceremoniously dragged him away through the light snow and slush to the roadside verge. There he gave the body one sharp kick. ‘Guns ’N’ Roses,’ he muttered to himself.

The Russians had turned the Toyota around as ordered, and were anxiously awaiting permission to leave. Both were making certain they avoided any eye contact with her.

‘Get the fuck out of here,’ the leader said contemptuously, and the car accelerated away, bullets flying above it from the guns of the grinning Chetniks.

She stood there, waiting for them to do whatever they were going to do.

The CO’s office looked much as Docherty remembered it: the inevitable mug of tea perched on a pile of papers, the maps and framed photographs on the wall, the glimpse through the window of bare trees lining the parade ground, and beyond them the faint silhouette of the distant Black Mountains. The only obvious change concerned the photograph on Barney Davies’s desk: his children were now a year older, and his wife was nowhere to be seen.

‘Bring in a cup of tea,’ the CO was saying into the intercom. ‘And a rock cake?’ he asked Docherty.

‘Why not,’ Docherty said. He might as well get used to living dangerously again. There were some at the SAS’s Stirling Lines barracks who claimed that the Regiment had lost more men to the Mess’s rock cakes than to international terrorism. It was a vicious lie, of course – the rock cakes were disabling rather than lethal.

‘Is there any news of Reeve?’ Docherty asked.

‘None, but his wife’s still in Sarajevo, working at the hospital as far as we know.’

‘Where’s the information coming from?’

‘MI6 has a man in the city. Don’t ask me why. The Foreign Office has got him digging around for us.’

Docherty’s tea arrived, together with an ominous-looking rock cake. ‘I’m hoping to take her with me,’ he told Davies. ‘Even if they’ve separated I still think he’s more likely to listen to her than anyone else.’

‘Well, you can ask her when you get there…’

‘Sarajevo?’ Docherty asked, his mouth half full of what tasted like an actual rock. Sweet perhaps, but hard and gritty all the same.

‘It’s not been a very good year for them,’ Davies said, observing the expression on Docherty’s face, and causing the Scot to wonder whether the CO had racks of the damn things in his cellar, each bearing their vintage.

‘Sarajevo looks like the best place to begin,’ Davies continued. ‘Nena Reeve is there, and your MI6 contact. His name’s Thornton, by the way. There must be people from Zavik who can fill you in on the town and its surroundings. Plus, there’s the UN command and a lot of journalists. You should be able to pick up a good idea of what the best access route is, and what to expect on the way. Always assuming we can get you into the damn city, of course.’

‘I thought the airport was closed.’

‘Opened again a couple of days ago for relief flights, but there’s no certainty it will still be open tomorrow. If it’s not the Serbs lobbing shells from the hilltops it’s the Muslims and Serbs exchanging fire across the damn runway, and even if they’re all on their best behaviour it’s probably only because there’s a blizzard.’

‘Lots of package tours, are there?’ Docherty asked.

‘The more I know about this war the less I’m looking forward to seeing any of my men involved in it,’ Davies said.

Docherty took a gulp of tea, which at least scoured his mouth of cake. ‘How many men am I taking in?’ he asked.

‘It’s up to you, within reason. But I’d stick with a four-man patrol…’

‘So would I. Are Razor Wilkinson and Ben Nevis available?’ Darren Wilkinson and Stewart Nevis were two of the three men who had been landed on the Argentinian mainland with him during the Falklands – the third, Nick Wacknadze, had left the SAS – and Docherty had found both to be near-perfect comrades-in-arms.

‘Nevis is in plaster, I’m afraid. He and his wife went skiing over Christmas – French Alps, I think – and he broke a leg. Sergeant Wilkinson is around, though. And I think he’ll probably jump at the chance to get away from mothering the new boys up on the Beacons.’

‘Good. I’ve missed his appalling cockney sense of humour.’

‘Any other ideas?’

Docherty thought for a moment. ‘I’m out of touch, boss…’

‘Do you remember the Colombian business?’ Davies asked.

‘Who could forget it?’

Back in 1989 an SAS instructor on loan to the Colombian Army Anti-Narcotics Unit had been kidnapped, along with a prominent local politician, by one of the cocaine cartels. A four-man team had been inserted under cover to provide reconnaissance, and then an entire squadron parachuted in to assist with the rescue. One of the helicopters sent in to extract everyone was destroyed by sabotage and the original four-man patrol, plus the instructor, had been forced to flee Colombia on foot. In the process two of them had been killed, but the patrol’s crossing of a 10,000-foot mountain range, pursued all the way by agents of the cartel, had acquired almost legendary status in Special Forces circles.

‘Wynwood’s in Hong Kong,’ Davies said, ‘but how about Corporals Martinson and Robson? They’ve proved they can walk across mountains, and it seems Yugoslavia – or whatever we have to call it these days – is full of them. And’ – the CO’s face suffused with sudden enthusiasm – ‘I have a feeling Martinson has another useful qualification.’ He reached for the intercom. ‘Get me Corporal Martinson’s service record,’ he told the orderly.

Docherty sipped his tea, allowing Davies his moment of drama.

The file arrived, Davies skimmed through it, and stabbed a finger at the last page. ‘Serbo-Croat,’ he said triumphantly.

‘What?’ Docherty exclaimed. He could hardly believe there was a Serbo-Croat speaker in the Regiment.

‘You know what it’s like,’ Davies said. ‘The chances for action are few and far between these days, so the moment some part of the world looks like going bad the keen ones pick that language to learn, just in case. If nothing happens, any new language is still a plus on their record, and if by chance we get involved, they’re first in the queue.’

‘Looks like Martinson’s won the jackpot this time,’ Docherty said, reaching for the file to examine the photograph. ‘He even looks like a Slav,’ he added.

‘He’s a medic, like Wilkinson, but that might well come in useful where you’re going. And he’s a twitcher, too. A bird-watcher,’ Davies explained, seeing the expression on Docherty’s face. ‘Bosnia’s probably knee-deep in rare species.’

‘I’ll keep my eyes open,’ Docherty said drily. He had never been able to understand the fascination some people had with birds. ‘What about Robson?’

‘He’s an explosives man, and a crack shot with a sniper rifle. Which leaves you without a signals specialist, but I imagine you can fill in there yourself.’

‘Those PRC 319s work themselves,’ Docherty replied, ‘and anyway, who will we have to send signals to?’

‘Well, you might need to make contact with one of the British units who are serving with the UN.’

‘But they wouldn’t be able to get involved with this mission?’

‘No, and in any case you won’t be in uniform. This mission is about as official as Kim Philby’s.’

‘So when it comes down to it we’re just a bunch of Brits dropping in to help out a mate.’

Davies opened his mouth to object, and closed it again. ‘I suppose you are,’ he agreed.

A little more than twenty miles to the south, Chris Martinson was moving stealthily, trying not to step on any of the twigs spread across the forest floor. He halted for a moment, ears straining, and right on cue heard the ‘yah-yah-yah’ laughing sound. It was nearer now, but he still couldn’t see the bird. And then, suddenly, it seemed to be flying straight towards him down an avenue between the bare trees, its red crown, black face and green-gold back looking almost tropical in the winter forest. It seemed to see him at the last moment, and veered away to the left, into a stand of conifers.

The green woodpecker wasn’t a rare bird, but it was one of Martinson’s favourites, and, since a day trip from Hereford to the Forest of Dean never seemed quite complete if he didn’t see one, there was a smile on his face as he continued his walk.

Another quarter of a mile brought him to the crown of a small hill giving a view out across the top of the trees towards the Severn Estuary. Some kind soul had arranged for a wrought-iron seat to be placed there, and Chris gratefully sat himself down, putting his binoculars to one side and unwrapping the packed lunch he had brought with him. As he bit into the first tuna roll a flock of white-faced geese flew overhead towards the estuary.

It had been a good idea to come out for the day, Chris decided. The older he got the more claustrophobic the barracks seemed to get. He supposed it was time he got a place of his own, but somehow he had always resisted the idea. Flats were hard to find and you had all the hassle of dealing with a landlord, and as for buying somewhere…well, it would only be a millstone round his neck when he eventually left the Regiment and did some serious travelling.

He had turned thirty that year, and the time for decision couldn’t be that far off. And, he had to admit, he was getting bored with the same old routines – routines that only seemed to be interrupted these days by a few hairy weeks in sun-soaked Armagh or exotic Crossmaglen. Even the birds in Northern Ireland seemed depressed by the weather.

He ran a hand through his spiky hair. His life was in a rut, he thought. Not an unpleasant one – in fact quite a comfortable one – but a rut nevertheless. He hadn’t really made any close friends in the Regiment since Eddie Wilshaw, and the man from Hackney had died in Colombia three years before. And he hadn’t had anything approaching a relationship with a woman for almost as long. The last one he’d gone out with had told him he seemed to be living on a separate planet from the rest of humanity.

He smiled good-naturedly at the memory. She was probably right, and it was no doubt time he started reaching out to people a bit more, but…

A robin landed in a tree across the clearing and began making its ‘tick’ calling sound. Chris sat there watching it, feeling full of nature’s wonder, thinking that life on your own planet had its compensations.

3

Docherty could hear the familiar London accent before he was halfway down the corridor.

‘…and in hot climates there’s one last resort when it comes to infected wounds. Any ideas?’

‘A day on the beach, boss?’ a northern voice asked.

‘Several rum and cokes?’

‘I can see you’ve all read the book. The answer is maggots. Since they only eat dead tissue they act as cleaning agents in any open wound…’

‘But boss, if I’ve just been cut open by some guerrilla psycho with a machete I’m probably going to be a long way from the local fishing tackle shop…’

‘No problem, Ripley. Once the wound gets infected you can just sit yourself down somewhere and ooze pus. The maggots will come to you. Especially you. Right. Yesterday you were all given five minutes to write down the basic rules of dealing with dog bites, snake bites and bee stings. Most of you managed to survive all three. Trooper Dawson, however,’ – a collective groan was audible through the room’s open skylight – ‘used the opportunity to attempt suicide. He didn’t report the dog bite, so he may have rabies by now. It’s true that in this country he’d need to be very unlucky, but the Regiment does occasionally venture abroad. And it doesn’t really matter in any case because the snake got him. He not only wasted time trying to suck out the venom, but managed to lose an arm or a leg by applying a tourniquet instead of a simple bandage. Of course he probably didn’t notice the limb dropping off because of the pain from the bee sting, which he’d made worse by squeezing the poison sac.’

In his mind’s eye Docherty could see the expression on Razor’s face.

‘Well done, Dawson,’ Razor concluded. ‘Your only worry now is whether your mates will bother to bury you. Any questions from those of you still in the land of the almost-living?’

‘What do you do about a lovebite from a beautiful enemy agent?’ a Welsh voice asked.

‘In your case, Edwards, dream of getting one. Class dismissed. And read the fucking book.’

The Continuation Training class filed out, looking as young and fit as Docherty remembered being twenty years before. When the last man had emerged he could see Darren Wilkinson bent over a ring binder of notes on the instructor’s desk. Razor looked, like Docherty himself, as wiry as ever, but there was a seriousness of expression on the face which Docherty didn’t remember seeing very often in the past. Maybe life in the Training Wing was calming him down.

Razor looked up suddenly, conscious of someone’s eyes on him, and his face slowly split open in the familiar grin. ‘Boss. What are you doing here? If you’ve not retired I want my twenty pee back.’

‘Which twenty pee might that be?’

‘The one I gave to your passing-out collection.’

Docherty sat down in the front row and eyed him tolerantly. ‘I’m recruiting,’ he said.

‘What for?’

‘A journey into hell by all accounts.’

‘Forget it. I’m not going to watch Arsenal for anybody.’

‘How about Red Star Sarajevo?’

Razor lifted himself on to the edge of the desk. ‘Tell me about it,’ he said.

‘Do you know John Reeve?’ Docherty asked.

‘To say hello to. Not well. I never did an op with him.’

‘I did,’ Docherty said. ‘Several of them. We may not have actually saved each other’s lives in Oman, but we probably saved each other from dying of boredom. We became good mates, and though we never fought together again, we stayed that way, you know the way some friends are – you only need to see them once a year, or even every five years, and it’s still always like you’ve never been apart.’

He paused, obviously remembering something. ‘Reeve was one of the people who helped me through my first wife’s death. In fact if he hadn’t persuaded me to get compassionate leave rather than simply go AWOL I’d have been out of this Regiment long ago…Anyway, I was best man at his wedding, and he was at mine. And we both married foreigners, which sort of further cemented the friendship. You know my wife – you were there when we met…’

‘Almost. I was there when you had your first argument. About which way we should be running, I think.’

‘Aye, well, we’ve had a few since, but…’ Docherty smiled inwardly. ‘Reeve married a Yugoslav, a Bosnian Muslim as it turns out, though no one seemed too bothered by such things back in 1984. He and Nena had two children, a girl first and then a boy, just like me and Isabel. Nena seemed happy enough living in England, and then about eighteen months ago Reeve got an advisory secondment to the Zimbabwean Army. I haven’t seen him since, and I hadn’t heard anything since last Christmas, which should have worried me, but, you know how it is…Then last week, two days before Christmas, the CO comes to visit me in Glasgow.’

‘Barney Davies? He just turned up?’

‘Aye, he did.’

‘With news of Reeve?’

‘Aye.’

Docherty told Razor the story as Davies had told it to him, ending with the CO’s request for him to lead in a four-man team.

‘And it looks like you said yes.’

‘Aye, eventually. Christ knows why.’

‘Have they reinstated you?’

‘Temporarily. But since the team won’t be wearing uniform, and will have no access whatsoever to any military back-up it doesn’t seem particularly relevant.’

Razor stared at him. ‘Let me get this straight,’ he said eventually. ‘They want us to fight our way across a war zone so we can have a friendly chat with your friend Reeve, either slap his wrist or not when we hear his side of the story, and then fight our way back across the same war zone. And we start off by visiting the one city in the world which no one can get into or out of.’

Docherty grinned at him. ‘You’re in, then?’

‘Of course I’m fucking in. You think I like teaching first aid to ex-paras for a living?’

‘I now pronounce you man and wife,’ the vicar said, and perhaps it was the familiarity of the words which jolted Damien Robson out of his reverie. The Dame, as he was known to all his regimental comrades, cast a guilty glance around him, but no one seemed to have noticed his mental absence from the proceedings.

‘You may kiss the bride,’ the vicar added with a smile, and the Dame’s sister, Evie, duly uplifted her face to meet the lips of her new husband. She then turned round to find the Dame, and gave him an affectionate kiss on the cheek. ‘Thank you for giving me away,’ she said, her eyes shining.

‘My pleasure,’ he told her. She seemed as happy as he’d ever seen her, he thought, and hoped to God it would last. David Cross wasn’t the man he would have chosen for her, but he didn’t actually have anything specific against him. Yet.

The newly-weds were led off to sign the register, and the Dame walked out of the church with the best man to check that the photographer was ready. He was.

‘We haven’t seen you lately,’ a voice said in his ear.

He turned to find the vicar looking at him with that expression of pained concern which the Dame had always associated with people who were paid to care. ‘No, ’fraid not,’ he replied. ‘The call of duty,’ he explained with a smile.

The vicar examined the uniform which Evie had insisted her brother wear, his eyes coming to rest on the beige beret and its winged-dagger badge. ‘Well, I hope we see you again soon,’ he said.

The Dame nodded, and watched the man walk over to talk with his and Evie’s sister, Rosemary. A couple of years before, after the Colombian operation, he had started attending church regularly, this one here in Sunderland when he was at home, and another on the outskirts of Hereford during tours of duty. He could have used the Regimental chapel, but, without being quite sure why, had chosen to keep his devotions a secret from his comrades. It wasn’t that he feared they’d take the piss – though they undoubtedly would – it was just that he felt none of it had anything to do with anyone else.

He soon realized that this feeling encompassed vicars and other practising Christians, and in effect the Church itself. He stopped attending services, and started looking for other ways of expressing a yearning inside him which he could hardly begin to explain to himself, let alone to others. He wasn’t even sure it had anything to do with God – at least as other people seemed to understand the concept. The best he could manage by way of explanation was a feeling of being simultaneously drawn to something bigger than himself, something spiritual he supposed, and increasingly detached from the people around him.

The latter feeling was much in evidence at the wedding reception. It was good to see so many old friends: lads he’d been to school with, played football with, but none of them seemed to have much to say to him, and he couldn’t find much to say to them. A few old memories, a couple of jokes about Sunderland – town and football team – and that was about it. Most of them seemed bored with their jobs and, if they were married, bored with that too. They seemed more interested in one another’s wives than their own. The Dame hoped his sister…well, if David Cross cheated on her then the bastard would have him to deal with.

The time eventually arrived for the honeymooners’ departure, their hired car trailing its retinue of rattling tin cans. Soon after that, feeling increasingly oppressed by the reception’s accelerating descent into a drunken wife-swap, the Dame started off across the town, intent on enjoying the solitude of a twilight walk along the seafront.

It was a beautiful day still: cold but crystal-clear, gulls circling in the deepening blue sky, above the blue-grey waters of the North Sea. He walked for a couple of miles, up on to the cliffs outside the town, not really thinking about anything, letting the wind sweep the turmoil of other people from his mind.