0

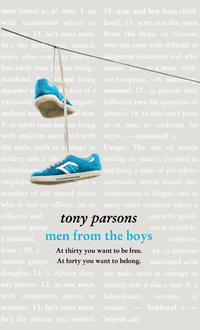

0Men from the Boys

‘Our mob are marching,’ he said, ‘that’s why I’m here.’

Then I watched in horror as he took out a pack of cigarettes with a death’s head covering most of the packet. Perhaps I imagined it, but I think I heard Cyd’s intake of breath.

‘Didn’t have any Old Holborn in your newsagent,’ he told me, as if I was personally to blame. ‘The geezer didn’t seem to know what I was talking about. Foreign chap.’

The children were all staring at him, their dinner forgotten. They had never seen someone taking out a pack of fags in our house – or any house – before. That twenty-pack of Silk Cuts had the exotic danger of an Uzi, or a gram of crack cocaine, or a ton of bootleg plutonium.

‘You know,’ Ken said. ‘At the Cenotaph. The eleventh hour of the eleventh month of the eleventh day.’ He stuck a Silk Cut in his mouth. ‘Nearest Sunday, anyway,’ he said, fumbling in his blazer for a light. ‘What did I do with those Swan Vestas?’ he muttered.

My wife looked at me as if she would tear out my heart and liver if I did not stop him immediately. So I took his arm and gently steered him to the back garden.

I sat him down at the little table at the back, just beyond the Wendy House. Through the glass I could see my family eating their dinner. Joni was still laughing at the hilarity of someone saying ‘arse’ and thinking they could smoke in our house.

And I realised that Ken Grimwood talked about my father in the present tense.

‘But he died ten years ago,’ I said, afraid he might unravel. ‘More than ten years. Lung cancer.’

Ken just looked thoughtful. Then he struck a match, lit up and sucked hungrily on his Silk Cut. I had brought a saucer out with me – we hadn’t owned an ashtray since the last century – and I pushed it towards him.

‘I’m sorry,’ I said. ‘Someone should have told you.’

He took it surprisingly well. Perhaps he had seen enough death – as a young man, as an old man – to vaccinate him against the shock. I had seen a few of them over the years – those old men from my dad’s mob. I remembered their green berets at the funeral of my father, and later my mother, although there were less of them by then. But Ken Grimwood was new to me.

‘You lose touch over the years,’ he said, by way of explanation. ‘Some of our mob – well, they liked the reunions, the marching, putting on the old medals.’ He considered his Silk Cut and coughed for a bit. ‘That wasn’t for me.’ He looked at me shrewdly. ‘Or your old man.’

It was true. For most of his life, my father never gave me the impression that he wanted to remember the war. Forgetting seemed like more his thing. It was only towards the end, when the time was running out, that he talked about going back to Elba, and seeing the graves of boys that he had known and loved and lost before they were twenty. But he never got around to it. No time.

And it turned out that Ken Grimwood’s time was running out too.

‘Lung cancer,’ he said casually. ‘Yeah, that’s what I’ve got.’

He stubbed out his Silk Cut, lit up another and saw me looking at him, and his cigarette, and his fag packet with a skull. ‘You’ve got to go sometime, son,’ he chuckled, dry-eyed and enjoying my shock. ‘I reckon I’ve had a good innings.’

And we sat there in the twilight until he could not force any more smoke into his dying lungs, and my meatballs had gone stone cold.

I walked him to the bus stop at the end of our road.

It took some time. I had not noticed until we were out on the street that he had a slow, strange walk – this laborious, rolling gait. When we finally got there I shook his hand and went back home.

Cyd was watching the bus stop from the window. She’s a kind person, and I knew she would not approve of me abandoning him on the mean streets of Holloway.

‘But you can’t just leave him out there, Harry,’ she said. ‘It’s dangerous.’

‘He’s a former Commando,’ I said. ‘If he’s anything like my dad, he’s probably killed dozens of Nazis and he’s probably had bits of old shrapnel worming its way out of his body for the last sixty years. He can catch a bus by himself. He’s only going to the Angel.’

She started to follow me into the kitchen. And then she stopped. And I heard it too.

A smack of air, then breaking glass, and then laughter. And again. The crack of air, the breaking glass, and laughter. We went back to the window and saw the two men standing in front of the house across the street.

No, not men – boys.

A security light came on – the kind of blinding floodlight that was becoming increasingly popular on our street – and illuminated William Fly and his mate, a spud-faced youth who cackled by his side, every inch the bully’s apprentice.

Fly lifted his hand, pointing it at the light, and I heard my wife gasp beside me as the air pistol fired.

The security light went dark in a tinkle of glass and a ripple of laughter.

They moved on down the street, letting the next security light come on, and I was glad that we had decided against getting one. Fly shot out that light too, and they sauntered on, down to the bus stop where the old man was sitting.

My wife looked at me, but I just kept staring out the window, willing the bloody bus to come.

The two boys looked down at the old man.

He stared at them curiously. They were saying something to him. He shook his head. I saw the air pistol being brandished in the right hand of William Fly.

Then my wife said my name.

And we both saw the glint of the blade.

I was out of the house and running down the street, a diminished number of the security lights coming on as I went past them, and I was almost upon them when I realised that the knife was in the hand of the old man.

And they were laughing at him.

And as I watched, Ken Grimwood jammed the blade deep into his left leg.

As hard as he could, just below the knee, half of the blade disappearing into those neatly pressed trousers and the flesh beneath. And he did not even flinch.

There was a long moment when we stood and stared at the knife sticking out of the old man’s leg.

Me. And the boys. And then William Fly and Spud Face were gone, and I was approaching Ken Grimwood as if in a dream.

Still sitting at the bus stop, still showing no sign of pain, he pulled out his knife and rolled up his trousers.

His prosthetic leg was pink and hairless – that’s what struck me, the lack of hair – and it was like a photograph of a limb rather than the thing of flesh and blood and nerves that it had replaced.

And all at once I understood why this old man had not been at Elba with my father.

Two

By the time I came down the dishes from last night were clean and drying, and there was tea and juice on the table.

Pat was shuffling about the kitchen. I could smell toast. I went to pull the newspaper from the letterbox and when I came back he was putting breakfast on the table.

The girls were still upstairs. Pat was Mister Breakfast. He had been Mister Breakfast since the time he had been old enough to boil a kettle. That was the thing about the pair of us – it worked. And it had always worked.

The thing that used to get on my nerves was when people said to me, ‘Oh, so you’re his mother as well as his father?’ I could never work that one out.

I was his father. And if his mother wasn’t around, then I could still only be his father. If you lose your right arm, does your left arm become both your right and left arm? No, it doesn’t. It’s still just your left arm. And you get on with it. Both his mother and his father? Hardly. It took everything I had to pull off being his dad.

‘You all right?’ he said, wiping his hands on the dishcloth, looking at me sideways.

‘Fine,’ I said. ‘All good.’

And still I did not mention his mother.

Joni appeared. At seven, her footsteps were so light that, if she was not rushing somewhere, or talking, or singing, you often did not hear her coming. You turned around and she was just there. She shuffled slowly towards the table, dressed for school but still more asleep than awake.

She yawned widely. ‘I don’t want to eat anything today,’ she said.

‘You have to eat something,’ I said.

She cocked a leg and hauled herself up on her chair, like a cowboy getting on his horse.

‘But look,’ she said.

She opened her mouth and as Pat and I bent to peer inside, she began to manoeuvre one of her front teeth with her tongue. It was so loose that she could get it horizontal.

She closed her mouth. Her eyes shone with tears. Her chin wobbled.

Pat went off to the kitchen and I sat down at the table. ‘Joni,’ I said, but she held up her hands, cutting me off, pleading for understanding.

‘Cereal hurts my gums,’ she said, waving her hands. ‘Not just Cookie Crisps. All of them.’

I touched her arm. Upstairs I could hear Cyd and Peggy laughing outside the bathroom door. I groped for the correct parental soundbite.

‘Breakfast is, er, the most important meal of the morning,’ I reminded her, but my daughter looked away with frosty contempt, furiously worrying at her wonky tooth with the tip of her tongue.

‘There you go,’ Pat said.

He placed a sandwich in front of Joni. Two slices of lightly toasted white bread with the crusts removed, the chemical yellow of processed cheese sticking out of the sides like a toxic spill. Cut into triangles.

Her favourite.

Pat returned to the kitchen. I picked up the newspaper. Joni lifted the sandwich in both hands and began to eat.

Here’s a good one for the Lateral Thinking Club – if a marriage produces a great child, then can that marriage ever be said to have failed?

If the marriage produces some girl or boy who just by existing makes this world a better place, then has that marriage failed just because Mum and Dad have split up? Is the only criterion of a successful marriage staying together? Is that really all it takes? Hanging in there? Butching it out?

Does my friend Marty Mann have a successful marriage because it has lasted for years? Does it matter that he likes his Latvian lap dancers two at a time before going home to his wife? Has he got a successful marriage because it remained untouched by the divorce courts?

If a woman and a man abandon their wedding vows and run eagerly through all the usual hateful clichés – saying hurtful things, sleeping with other people, cutting up clothes, running off with the milkman – then is that a failed marriage?

Well, obviously. It’s a bloody disaster.

But still – I could not bring myself to call my union with my first wife a failed marriage. Despite everything. Despite crossing the border between love and hate and then going so far into alien territory that we could not even recognise each other.

Gina and I were young and in love. And then we were young and stupid, and getting everything wrong.

First me. Then both of us.

But a failed marriage? Never.

Not while there was the boy.

As the record came to an end, I looked at Marty’s eyes through the studio’s glass wall.

‘Line two,’ I said into the microphone, ‘Chris from Croydon.’ Marty’s fingers flew across the board, as natural as a fish in water, and the light on the mic in front of him went red.

Marty adjusted himself in his chair, and leaned into the mic as if he might snog it.

‘You’re with Marty Mann’s Clip Round the Ear live here on BBC Radio Two,’ Marty said, half-smiling. ‘Enjoying good sounds in bad times. Mmmm, I’m enjoying this ginger nut. Chris from Croydon – what’s on your mind, mate?’

‘I can’t go to the pictures any more, Marty. I just get too angry – angry at the sound of some dopey kid munching his lunch, and angry at the silly little gits – can I say gits? – who think they will disappear into a puff of smoke if they turn their Nokias off for ninety minutes, and angry at the yak-yak-yak of gibbering idiots – ’

‘Know what you mean, mate,’ Marty said, cutting him off. ‘They should be shot.’

‘Whitney Houston,’ I said, leaning forward. ‘“I Will Always Love You”.’

‘And now a song written by the great Dolly Parton,’ Marty said. He knew music. He was from that generation that had music at the centre of its universe. This wasn’t just a hit song from a Kevin Costner film to him. ‘Before all music started sounding like it was made from monosodium glutamate.’

This was the starting point for our show – nothing was as good as it used to be. You know, stuff like pop music, and the human race.

Whitney’s cut-glass yearning began and Marty gave me a thumbs-up as he whipped off his headphones. He barged open the door. ‘Four minutes thirty-seconds on Whitney,’ I said.

‘Great, I can pee slowly,’ he said. ‘What’s next?’

I consulted my notes. ‘Let’s broaden it out,’ I said. ‘Nonspecific anger. Rap about being angry about everything. Being angry with people who litter. Yet also angry with people who make you recycle. Angry about people who swear in front of children, angry at traffic wardens, angry at drivers who want to kill your kids.’

‘Those bastards in Smart cars,’ Marty said, as he kept moving.

‘People, really,’ I said, calling after him. ‘Feeling angry at people. Any kind of rudeness, finger wagging or ignorance. And then maybe go to a bit of Spandau Ballet.’

‘I can do that,’ he said, and then he was gone.

‘Two minutes forty on and we’re back live,’ said Josh, the Oxford graduate who ran our errands – the BBC was full of them, all these Oxbridge double-firsts chasing up wayward mini-cabs – and I could hear the nerves in his voice. But I just nodded. I knew that Marty would be back just as Whitney was disappearing from Kevin Costner’s life forever. We were not new to this.

Marty and I were back on radio now – a couple of old radio hams who had taken a beating on telly and crawled back to where we had begun. It happens to guys like us. In fact, I have often thought that it is the only thing that happens to guys like us. One day the telly ends. But we were making a go of it. A Clip Round the Ear was doing well – we had that glass ear awarded by our peers to prove it. Ratings were rising for a show that played baby boomer standards and boldly proclaimed that everything was getting worse.

Music. Manners. Mankind.

I watched Marty come out of the gents, clumsily fumbling with the buttons on his jeans – I know he was angry about there never being zips on jeans – and saw a couple of guests for the show next door do a double take. Since his golden years as the presenter of late-night, post-pub TV, he had put on a little weight and lost some of that famous carrot-topped thatch. But people still expected him to look as he did when he was interviewing Kurt Cobain.

‘What?’ he said.

‘Nothing,’ I said, and I felt an enormous pang of tenderness for him.

Being on television is a lot like dying young. You stay fixed in the public imagination as that earlier incarnation. Someone who interviews the young and thin Simon Le Bon – they do not grow old as we grow old. But every TV show comes to an end. And, as Marty was always quick to point out, even the true greats – David Frost, Michael Parkinson, Jonathan Ross – have their wilderness years, the time spent working in Australia or getting rat-faced in the Groucho Club, waiting for the call to come again.

Marty settled himself in front of the mic, and pulled on his headphones. I didn’t know if Marty – and by extension, his producer: me – would ever get that call. For every great who comes again there are a thousand half-forgotten faces who never do come again. As much as I loved him, I suspected that Marty Mann was more of a Simon Dee than a David Frost.

‘You are angry because you know how things should be,’ Marty was saying to his constituency, as he teed up Morrissey. ‘Anger comes with experience, anger comes with wisdom. This is A Clip Round the Ear saying embrace your anger, friends. Love your anger. It is proof that you are alive. And – how about a bit of English seaside melancholia: “Everyday Is Like Sunday”.’

Then the two hours were up and we gathered our things and got ready to go home. That was a sign of the times. When we worked on The Marty Mann Show – when he was television’s Marty Mann – we always hung around for hours when we were off air, working our way through the wine, beer and cheese and onion crisps in our lavish green-room banquet, coming down off of that incredible rush you only get from live TV – even if you are behind the cameras. When we were doing The Marty Mann Show ten years ago, we could carouse in the green room until the milkman was on his way. But that was telly then and this was Radio Two now.

Broadcasting House was a bit of a dump when it came to post-gig entertainment. The place did not encourage loitering, or hospitality, or lavish entertaining. There wasn’t a sausage roll in sight. You did your gig and then you buggered off. There was nothing there – just a couple of smelly sofas and some tragic vending machines.

The green room. That was another thing that wasn’t as good as it used to be.

Gina was waiting for me when I came out of work.

Standing across the street from Broadcasting House, in the shadow of the Langham Hotel, just where the creamy calm of Portland Place curves down to the cheapo bustle of Oxford Circus.

She looked more like herself now – or at least I could recognise the woman I had loved. Tall, radiant Gina. Loving someone is a bit like being on TV. A face gets locked in a memory vault, and it is a shock to see it has changed when you were not looking. We both took a step towards each other and there were these long awkward moments as the cars whizzed between us. Then I shouldered my bag and made it across.

‘I couldn’t remember if you were live or not,’ she said.

‘What?’

‘The show,’ she said. ‘I didn’t know if you recorded it earlier. Or if it really was ten till midnight.’

I nodded. ‘A bit late for you, isn’t it?’

‘My body’s still on Tokyo time,’ she said. ‘Or somewhere between there and here.’ She attempted a smile. ‘I’m not sleeping much.’

We stared at each other.

‘Hello, Harry.’

‘Gina.’

We didn’t kiss. We went for coffee. I knew a Never Too Latte just off Carnaby Street that stayed open until two. She took a seat in the window and I went to the counter and ordered a cappuccino with extra chocolate for her and a double macchiato for myself. Then I had to take it back because she had stopped drinking coffee during her years in Tokyo and only drank tea now.

‘How well you know me,’ she said after I had persuaded some Lithuanian girl to exchange a coffee for tea. Was she that sharp when we were together? I don’t think so. She was another one who had got angrier with the years.

‘Sorry,’ I said. ‘Stupid of me not to read your mind.’

And we took it from there.

‘Japan’s over,’ she said. ‘The economy is worse than here.’

‘Nowhere is worse than here,’ I said. ‘Ah, Gina. You could have called.’

‘Yes, I could have called. I could have phoned home and had to be polite to your second wife.’

‘She’s not my second wife,’ I said. ‘She’s my wife.’

My first wife wasn’t listening.

‘Or I could have phoned your PA at work and asked her if you had a window for me next week. I could have done all of that but I didn’t, did I? And why should I?’ She leaned forward and smiled. ‘Because he’s my child just as much as he’s your child.’

I stared at her, wondering if there ever came a point where that was simply no longer true.

And I wondered if we had reached that point years ago.

‘What’s with the keep-fit routine?’ I said, changing the subject. She was in terrific shape.

‘It’s not a routine.’ She flexed her arms self-consciously. ‘I just want to look after myself as I get older.’

I smiled. ‘I can’t see you on the yoga mat.’

She didn’t smile back. ‘I had a scare a couple of years back. A health scare. That was something you missed.’

‘Sorry.’

‘Please don’t apologise.’

‘Jesus Christ – why can’t you just let me say I’m sorry?’

‘And why can’t you just drop dead?’

We stared at our drinks.

We had started out with good intentions. Difficult to believe now, I know, but when we divorced back then we were a couple of idealistic young kids. We really thought that we could have a happy break-up. Or at least a divorce that always did the right thing.

But Gina had blown in and out of our lives. And gradually other things got in the way of good intentions. In my experience it is so easy to push good intentions to the back of the queue – or to have them quietly escorted from the building.

Gina wanted to be a good mother. I know she did. I know she loved Pat. I never doubted that. But she was always one step from fulfilment, and life got in the way, and everything let her down. Her second husband. Working abroad. And me, of course. Me first and worst of all.

We sat in silence for a bit.

‘Is this the way we are going to do it?’ I said.

‘What way?’

‘You know what way, Gina.’

‘What way do you want to do it? Shall we be nice to each other? First time for everything, I guess.’

‘I don’t want us to be this way,’ I said. ‘How long are we going to spit poison at each other?’

‘I don’t know, Harry. Until we get tired of the taste.’

‘I was tired years ago.’

We sat in silence as if the people we had once been no longer existed. As if there was nothing between us. And it wasn’t true.

‘He’s my son too,’ she said.

‘Biologically,’ I said.

‘What else is there?’

‘Are you kidding me? Look, Gina – I think it’s great you’re back.’

‘Liar.’

‘But I don’t want him hurt.’

‘How could he be hurt?’

‘I don’t know. New man. New job. New country. You tell me.’

‘You don’t break up with your children.’

‘I love it when people say that to me. Because it’s just not true. Plenty of people break up with their children, Gina. Mostly, they’re men. But not all of them.’

‘Do you want me to draw you a diagram, Harry?’

‘Hold on – I’ll get you a pen.’

I lifted my hand for the waitress. Gina pushed it down. It was the first time we had touched in years and years, and it was like getting an electric shock.

‘I broke up with you, Harry – not him. I went off you – not him. I stopped loving you – not him. Sorry to break this to you, Harry.’

‘I’ll get over it.’

‘But I never stopped loving him. Even when I was busy. Preoccupied. Absent.’ She sipped at her tea and looked at me. ‘How is he?’

‘Fine. He’s fine, Gina.’

‘He’s so tall. And his face – he has such a lovely face, Harry. He was always a beautiful kid, wasn’t he?’

I smiled. It was true. He was always the most beautiful boy in the world. I felt myself softening towards her.

‘He’s in the Lateral Thinking Club,’ I said, warming up to the theme, happy to talk about the wonder of our son, and we both laughed about that.

‘Bright boy,’ she said. ‘I don’t even know what Lateral Thinking is – thinking outside the box? Training the mind to work better?’

‘Something like that,’ I said. ‘He can explain it better than me.’ I had finished my coffee. I wanted to go home to my family. ‘What do you want, Gina?’

‘I want my son,’ she said. ‘I want to know him. I want him to know me. I know we – I – have wasted so much time. That’s why I want it now. Before it’s too late.’

And I thought it would never be too late. There was a Gina-sized hole in Pat’s life, had been for years, but I thought that it could never be too late to fill it. For both of them – I thought that there would always be time to put things right. That’s how dumb I am. Already my mind was turning to the practicalities of shipping Pat around town.