0

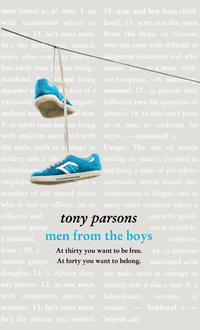

0Men from the Boys

‘Where you living, Gina?’

‘I’ve got a two-bedroom flat on Old Compton Street,’ she said. ‘Top floor. Plenty of space. Nice light.’ She looked out the window. ‘Five minutes from here.’

I was amused. ‘Soho?’ I said. ‘That’s an interesting choice. What you trying to do – recapture your youth?’

Her mouth tightened at that.

‘I didn’t have any youth, Harry,’ she said. ‘I was married to you.’

Then my phone began to vibrate. I took the call as Gina looked away and a woman with a Jamaican accent told me that they had Ken Grimwood at the hospital.

When he was seven years old my son almost drowned. We were in a quiet corner of Crete called Agios Stephanos – years before the island was claimed by the boys in football shirts – and the last thing we were expecting on our mini-break was death and tragedy. We could get all that at home.

These were the years after I split up with Gina, and then my dad died and then my mum got sick – and it felt like every time you turned around someone was either walking out or dying. We were not really in Crete for sun, sea and Retsina. We just wanted to catch our breath.

In my mind I see a windy, rocky beach. And I see Pat – all skinny limbs and tangled blond mop and baggy trunks, splashing out with a float while I settled down with a paperback.

My son at seven.

He made me smile, because he was wearing a pair of sunglasses that were way too big for him, purchased at the airport and proudly worn ever since, even at night. He would squint at his moussaka and chips in the Cretan twilight.

The waves were whipping up, but it did not cross my mind to be worried. He did not go far. But sometimes you do not have to go far to get into more trouble than you can handle. He had settled down on his float, got all dreamy in the sunlight and then he must have drifted. And by the time he noticed, it was more than drifting.

‘Dad!’

You know your child’s voice. Even on a crowded beach, with small children shouting and calling out on all sides, you know it instantly.

He was trying to stand up, although you couldn’t really stand up on that float, and he kept sinking to one knee as it threatened to pitch him into the sea. And he was scared. Face pale with fear behind those oversized sunglasses. Calling for me.

And I was on my feet and running, my heart a hammer as I ran to the water, suddenly aware of the speed of the clouds, suddenly noticing the swell of the waves, suddenly remembering that it can all fall apart at any moment.

He was a good swimmer. Even at seven. Maybe that’s why it happened, why I was too relaxed about letting him go out with a float. But suddenly it wasn’t enough that he could rescue a plastic brick while wearing his pyjamas.

I crashed through waves that seemed to be at once taking Pat out to open sea and smashing me back to the shore, switching between breaststroke and crawl and back again, getting a sickening gutful of water every time I called his name.

Finally I got to him. One hand on a corner of the float, another wrapped tight round a skinny limb. It was like trying to hold a fish.

And that was when he went into the water.

Flailing white limbs in the foggy depths. Silence, apart from the rushing sound in my ears. And then one of my arms wrapped around his waist as I kicked for the surface. The float was above our heads and somehow I got him on it and I made him lie flat on his belly, while I lumbered back to the beach, telling him that everything was all right. He clung on, somehow still wearing those oversized sunglasses and too numb to cry.

Then finally we were on the beach.

How bad was it? The parental mind has this endless ability to vault to the absolute worst-case scenario. No trouble at all. A parent panics not because of what is happening but because of what might.

But this was bad enough for everyone on the beach to put down their suntan lotion and copies of Captain Corelli’s Mandolin and stare at us even when it was clear that nobody was going to die, even as we staggered off to our shared hotel room, both salty with tears and regurgitated Aegean. Bad enough for me to remember for the rest of my life.

And what I remember most is the feeling of trying to reach my son as the sea and the wind and tide combined to push me back to the shore while they tried to carry Pat out to the open sea. That’s what I remember the most. Because sometimes it felt like that was the story of us, the story of me and my boy. Trying to reach each other, wanting to reach each other, but forever kept apart by forces that were bigger than both of us.

And the funny thing about calling your child’s name is that it doesn’t do a blind bit of good.

But you do it anyway.

Ken Grimwood sat propped up in his hospital bed in a robe that enveloped his small body like a circus tent, and when he grinned at me he was gummy as a newborn baby. On the bedside table, his false teeth sat in a glass of water.

‘They found him at the bus depot,’ a Filipina nurse told me. ‘He was unconscious. He couldn’t breathe. And he had a cigarette in his hand. We found this in his pocket.’

She handed me a BBC business card with my name on, as if I might want it back. And I remembered giving it to him before he left my house only because I wanted to get rid of him. And here he was, bounced back into my life because he had my card.

‘I hardly know him,’ I said, keeping my voice down. ‘He’s not actually anything to do with me.’

Ken laughed and we watched him produce a tin of Old Holborn and a packet of Rizlas from somewhere inside his giant robe. He must have been the only person left who wasn’t using roll-ups to smoke illegal substances. He flashed his toothless grin and as the nurse advanced towards him he stuck his smoking paraphernalia under the sheet.

‘Just pulling your leg, sweetheart,’ he said.

She took his blood pressure, shaking her head.

But when she left he produced his baccy tin and his papers. He winked at me slyly.

I walked down to the nurses’ station. The Filipina was there with a large Jamaican duty nurse. They looked at me as if I had done something wrong.

‘Your father is a very sick man,’ the duty nurse said. ‘There’s fluid on his lungs and I don’t know how much longer he can breathe unaided, okay? And of course you are aware that the cancer is at an advanced stage.’

‘He’s not my father,’ I said.

‘Friend of the family?’ the duty nurse asked.

‘I wouldn’t go that far,’ I said.

It was clear they wanted the bed. They wanted him out of there. But they would not discharge him without someone to take care of him. And I realised that just because I had been dumb enough to give him my business card, the National Health Service were nominating me.

‘I hardly know him,’ I told them. ‘He was a friend of my father’s. I’ve only met him once. I think he has children. Do his children know? Can’t his children come?’

The nurse looked at me as though I had suggested putting him in a plastic bag and leaving him on the pavement. But she talked to Ken and got a couple of telephone numbers from the old boy. There was a daughter in Essex and a son in Brighton. I quickly took out my phone and began calling.

I got through to an answer machine. And then another answer machine. I left messages on both – telling them what had happened to their father, telling them to come quick, telling them to call me back. Then I held my phone, expecting it to vibrate at any moment. But it did not stir, as if his children were reluctant to claim him too.

Down the hall I could hear a Jamaican accent telling Ken Grimwood that there was no smoking on hospital premises.

And as I stared at the silent phone in my fist, I could hear the mocking sound of the old man’s laughter.

Three

Joni grinned at me with her vampire smile.

Her two front teeth were both gone now. The wonky one had come out in her sandwich and the one next to it had quickly come out in sympathy. It must have been looser than she knew when she was focusing all her attention on the wonky one. So now when she smiled the milk teeth that remained at the sides of her mouth appeared like fangs.

‘I’ll brush my teeth,’ she said, and her gummy grin gave her a jaunty air, like a sailor on shore leave. ‘You get the book.’

‘Okay.’

She had strict bedtime rituals. When she was in her pyjamas and her remaining teeth had been cleaned, she hugged everyone who was in the house and told them she loved them. But she didn’t kiss anyone, because kissing was gross this year. Then she trooped up to her room and I read her a story. As she settled herself under the duvet, I looked at her bookcase for something suitable.

Joni was at that awkward age when she was getting too old for princesses and fairies but was still too young for anything to do with having a crush on boys. My wife and I had made half-hearted attempts to interest her in the Hannah Montana industry and the High School Musical business but when Joni watched the TV shows, or saw the DVDs, she was unmoved by all those white teeth, all that canned laughter and all those teenage children trying to talk like they were in a Neil Simon play. Joni was never going to go for cheesy American rubbish. So I stuck with the classics.

Terrible curses. Murderous adults. Wicked stepmothers. Beautiful maidens being taken to the woods for slaughter. Girls drugged and placed in glass coffins. All the stuff to give a seven-year-old a good night’s sleep.

Tonight it was Aurora.

We settled down. I had just got to the bit where Briar Rose had realised that the nice peasant boy and Prince Philip were – conveniently enough – one and the same when Joni yawned, lay back on her pillow and raised her hand, bidding me stop.

For a long time – years – Joni had been afraid of Maleficent, and at first I thought that she wanted me to stop before I reached the wicked witch losing her rag.

But it wasn’t that.

‘They all end the same way, don’t they?’ said my daughter. ‘The princess stories. They start off a bit different but they all end the same way. The prince saves them and they get married and they live happily ever after.’

I smiled and closed the book. ‘Well, it’s true,’ I said. ‘It’s always the same ending.’ I felt like kissing her on the cheek but I knew that wasn’t allowed. So I just touched her hair. ‘You’re getting a bit old for these stories now.’

She snuggled down and I pulled the duvet up to her chin.

‘It’s a load of arse,’ said my seven-year-old, and I cursed the day that Ken Grimwood had come to our door.

Elizabeth Montgomery was being dropped off at school.

She was in the car in front of us as I pulled up to let Pat out. And I know he saw her too, because he was perfectly still yet poised for flight, like a rabbit who suddenly realises that he is loitering in the fast lane of a motorway.

Elizabeth Montgomery wasn’t being dropped off by her dad. Not unless her dad had a barbed-wire tattoo at the top of his arm, and played the Killers at full volume at eight thirty in the morning in his souped-up BMW. Which I suppose was entirely possible in the lousy modern world.

In the passenger seat, Pat sat petrified.

‘Probably her brother,’ I said, but before the words were out the driver in front had his tongue in Elizabeth Montgomery’s ear, and she was laughing and squirming away. ‘More likely a cousin,’ I said.

And I felt like saying, Ah, don’t care so much, kiddo. Don’t be so quick to say, Here’s my heart. Why not have a game of five-a-side football with it? Go ahead. And I felt like saying, You will meet a dozen like Elizabeth Montgomery. A hundred.

But I didn’t, because I knew it was not true.

My son was almost fifteen years old and there would only ever be one Elizabeth Montgomery.

And I felt it again – I wanted to give him some sage advice. I wanted to say something meaningful about the fleeting nature of desire, or the way the person who cares the most is always the person who gets hurt the most.

I wanted to talk about love. But everything I could have said would have been about forgetting Elizabeth Montgomery. And I knew he could not do that.

So what I said was, ‘I saw Gina.’

He started at his mother’s name. A physical flinch, as if he had been struck. That is what it had come to.

He turned away from Elizabeth Montgomery in the car in front of us and looked at me. And I saw that his eyes were exactly the same colour as his mother’s eyes. This Pacific Ocean blue. The blue you see on a Tiffany catalogue. It is a special blue.

‘What do you mean – you saw her?’

‘She’s back from Japan,’ I said.

‘A holiday?’ he said.

‘Back for good. Back in London. She wants to see you.’

I have this theory about divorce. I have this theory that it is never a tragedy for adults and always a tragedy for children. Adults can lose weight, find someone nicer, get their life back. Divorce gives grown-ups a get-out-of-jail-free card. It is the children who pay the price, and pay it for the rest of their lives. But we can’t admit that, all us scarred veterans of the divorce court, because it would mean admitting that we have inflicted wounds on our children that they will carry for the rest of their lives.

Pat was looking back at Elizabeth Montgomery. But I don’t think he was seeing her any more.

‘How long…’

‘I saw her last week,’ I said. ‘She’s been back for about a month. She wants to see you.’

I watched the fury flush his face. ‘And you tell me now? You get round to telling me now?’

The children of divorced parents hold something back. They get so used to shuttling between warring homes when they are little that it stays with them. This restraint, this pragmatic reserve, this need to be a pint-sized Kofi Annan diplomat. So when they lose it, they really lose it.

He was out of the car, hauling out his rucksack, furious with me. I wasn’t so naïve that I thought it was just me that he was angry about. It was divorce, separation, the absent parent – it was the whole sorry package that he had been handed without ever asking for it.

‘You around tonight?’ I said.

‘I don’t know,’ he said, and he slammed the passenger door.

I watched him walk through the school gates, his rucksack slung over his shoulder, his shirt miraculously unfurling from his trousers, the swatch of white cloth that appeared as if from a magician’s hat. Then he was gone, but still I sat there, boxed in by the car in front and the car behind.

Watching Elizabeth Montgomery snog the boy with the barbed-wire tattoo, as the bell rang for registration.

Riddle me this, Lateral Thinking Club – she is my daughter but I am not her father: who am I?

I am a step-parent. Ah, but I don’t really believe in the term step-parent. I don’t think the role exists. Not really. For in the end you are either a child’s parent or you are not. And blood does not have a lot to do with it. At least, that is what I would like to believe.

Cyd and I watched Peggy coming down the stairs. She was almost exactly the same age as Pat and yet she seemed to be effortlessly gliding on air to adulthood. Peggy went to stage school, and every day of her life she danced and she sang, and she studied the performing arts and wrestled with the sub-text of difficult plays while other girls her age were snogging older boys with cars and barbed-wire tattoos. While other kids wore blazers, Peggy donned a black leotard and learned to dance jazz, ballet and tap. Above all, she wanted to act, following in the footsteps of Italia Emily Stella Conti, her school’s founder, and her father, a TV cop.

Peggy made life look easy.

Now she was all dressed up for going out – a cowboy hat, and cowboy boots, a retro Motorhead-London T-shirt and a skirt that was way too short. She kissed both of us on the cheek and glided off to the mirror in the hall. We could hear her humming a popular tune.

Cyd was looking at me and smiling. ‘Don’t say it,’ she said.

I looked dumb.

‘You know,’ she said. ‘“You’re not going out dressed like that.”’

What women forget is that men know boys. We know what is in their heads and in their hearts. We are all poachers turned gamekeepers. Every single one of us. And I knew that no boy was going to look at Peggy and think, Yeah, Motorhead, Lemmy and all that, yeah, they were a pretty good band. I knew exactly what they would be thinking, the dirty little bastards. And I didn’t like it.

‘It’s only her dad,’ Cyd said.

We heard a motorbike outside and Peggy ran to the door with a happy, ‘I’ll get it!’

Cyd gave me a look and drifted off to the kitchen. I went to the door and looked out at Peggy’s dad sitting astride his Harley.

Jim Mason. Ten years ago he was the bad boy. The deserter, the fornicator, the runaway. The absent father. But in recent years I had to admit Jim’s stock had risen. After a long, disorderly line of Asian girlfriends in the wake of his marriage to Cyd, he had been married to a nurse from Manila for years – but there had been no more children. And I suspected that must have been a relief for Peggy.

I never really spoke to the guy, beyond platitudes about what the latest weather meant for motorbikes. A couple of years ago, when his TV show was taking off – you might have seen him, he was the divorced, alcoholic detective on PC Filth: An Unfair Cop – he had offered to start paying Peggy’s school fees. I had brushed him off, told him that Cyd and I had it covered. But I felt that he could teach Gina and me a few lessons about how to conduct yourself after a divorce. Despite his inappropriately long hair, and Lewis Leathers, and past crimes, Peggy’s dad was living proof that you could be an absent parent and still be some kind of presence in your child’s life.

An absent parent but a parent still.

Peggy pulled on her helmet and climbed on to the pillion. They both raised their hands and I waved as they shot off, the throaty roar of the Harley ringing through the neighbourhood. The group of kids loitering at the end of the road watched them go. Long after they had disappeared, I could hear the growl of the motorbike.

And I felt a dull ache of resentment towards him. I could not help it. Because although the guy did his best to be a good dad to Peggy, there was so much he had missed. She was my daughter although I would never be her dad. We did not have the unbreakable bonds of blood, but we had something else.

I was the one who was there when, aged ten, she split her head open on the ice rink at Somerset House, foolishly attempting a complicated leap. And I was the one who was there when she endured two terms of bullying at her old school before we got her into Italia Conti. And I was there for other stuff – no blood, no tears. But meals shared together, and TV watched together, and holidays, and walking to school, and a good-night hug. Sometimes I think that stuff is more important than the times of high drama, when there is blood on the ice rink and a mad dash to Accident and Emergency.

She was not my daughter but we had been part of the same family for ten years. And I was more of a father to her than her real dad would ever be – wasn’t I?

Sometimes I thought so. But when she went off once a week on the Harley, looking so happy on that pillion, with her dad the big-shot actor, well, then I wasn’t so sure. And mostly I tried not to think about it at all.

Because it’s like someone says in The Terminator when cyborgs are coming back in time to murder children yet unborn:

You could go crazy thinking about this stuff.

Marty and I sat in the Pizza Express next to Broadcasting House and nobody looked at him twice.

TV fame is like youth or money. It just runs out when you are not looking. Ten years ago, Marty walked into a room and everybody stared at him. But the years on radio had eroded that recognition factor, and we were left unmolested by the early evening crowd.

Next to us was a table full of ageing lads in business suits. Their banter was of a sexual nature – birds and blow-jobs. Effing and blinding. Taking the front way and the back way. The usual stuff. Little did they know that they were next door to Marty Mann, the presenter formerly known as edgy and controversial.

And even less did they care.

It was the usual crowd. BBC worker bees grabbing some carbs before the evening shift. Office workers dawdling before they caught the train home. And revellers off to frolic in the tawdry lights of the West End.

The demographic skewed to a younger crowd – probably too young to listen to A Clip Round the Ear on Radio Two – but looking for a table among the funsters were a pair of old ladies who had big night out written all over them. I wondered what musical they were going to see, and I thought of my mum happily singing along to Chicago and Les Misérables and Guys and Dolls. It seemed like a lifetime ago now.

The old ladies carefully parked themselves two tables away from us. The lads in their suits were next door. And suddenly they seemed louder than ever.

‘No, fuck it, this is a true story,’ one of them said, holding his hands up at the derisive profanities of his chums. ‘Guy goes to a whore and says, “How much for a hand-job? One hundred quid? That’s a lot.” But the whore says, “Listen, see this Rolex, I bought it by giving hand-jobs.”’

Marty looked up at me from his Four Seasons. He glanced quickly at the old ladies and looked away. You would think that a man with Marty’s CV would not care about profanity in the pizza parlour. But, like all transgressors, he understood that context is everything.

The old ladies were staring at each other. The suits were in uproar. The comedian took a bite of garlic bread and ploughed on.

‘Next day he goes back and says to the whore, “How much for a blow-job?” She says, “Five hundred quid.” “Five hundred quid! Fuck me, that’s a lot of dough.” She says, “Listen, you see that Mercedes? I bought it by giving blow-jobs.”’

Marty pushed his pizza away.

‘We should say something,’ I said, my voice pathetically low. ‘We should say something to these creeps.’

Marty nodded. But he kept staring at his pizza. ‘Except there’s five of them,’ he said. ‘Except they might not like it. Except they might have knives.’

‘You kidding? These guys haven’t got knives. They’ve got BlackBerrys. What do you think they are going to do? Slash you with their iPhones?’

But for all my big talk, I sat there just like Marty, useless in my disapproval.

There was bedlam at the next table. Red faces. Drunken voices. The joke coming to its punchline. The old ladies were getting up to go. They were telling a confused waitress that they were not so hungry after all.

‘And then he goes to the whore and says, “How much for the lot?” And she says, “One thousand quid.” And he says, “Fuck my old boots, that’s a lot.” And she says, “See that big house over there?”’

‘She says, “If I had a pussy,”’ Marty muttered to himself, ‘“I bet I could buy that.”’

‘I feel like saying something,’ I said, staring at the suits as I watched the old ladies heading for the door, their big night out already violated.

But I just sat there, and I said nothing.

Four

I drove Pat to Soho. He was still not really speaking to me. We were on grunting terms.

I walked him to the door and found the bell with her surname. The name she had before me, the name she had after me. I looked at Pat as I rang it. He was impassive, neutral – the inscrutable offspring of divorced parents.

‘Hello?’

It was strange that I had not recognised her face. Because the voice could not belong to anyone else. Pat and I leaned towards the metal grille.

‘It’s us,’ I said.

‘It’s me,’ Pat said.

Gina laughed with delight – a sound that I had not heard in, oh, about a thousand years. ‘Great, come up,’ she said, and she buzzed the front door open. Pat gave me a blank look and went inside. I stood there for just a moment after the door swung shut.