0

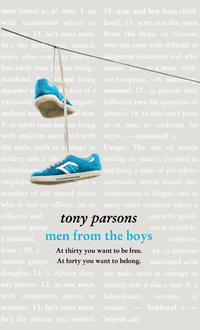

0Men from the Boys

I don’t know what I had been expecting. But I had driven him across town with a mounting sense of dread. And nothing had happened. Had it? I walked back to the car. But I did not get in. I just kept walking. And the reasons that we stay together or come apart just seemed so heartbreakingly random that I could have sat down in Old Compton Street and wept.

Would she take him out to dinner? Or would it be easier for both of them if they stayed home? They would talk, wouldn’t they? Or would Gina – would both of them – want to avoid too much talking, and just try to rack up some together time?

It’s their thing, I thought. And I was totally lost. I felt flat. And suddenly older.

If I had not slept with someone else, if she had given me another chance, if she had not been so quick to try again with another man…not much had to happen to keep us together, I thought.

But I was the child of a nuclear family, and growing up in a family that never comes apart makes you believe in the inevitability of staying together. And I could see that there was a banality about my expectations – like the predictability of the princess stories that my seven-year-old daughter had suddenly grown out of.

Gina came from a family where the father walked out. She did not expect happy endings. She did not expect families to stay together. She expected them to fall apart. I walked out of Soho and into Chinatown, reluctant to start the drive back across town in case it all went wrong, and there were accusations and raised voices and slammed doors and the call to come quick. I kept my phone in my hand in case it suddenly began to vibrate. But I walked all over Chinatown, and it never did.

Five good things about being a single parent.

You are alone now, so you can make all decisions concerning your kid without consultation.

You know, with total certainty, that a child only needs one good parent.

You know that your child is loved, and will always be loved.

There is no need to feel like a freak at the school gates, because the world is overflowing with single parents now.

And your ex is out of your life.

Five bad things about being a single parent.

You are alone now, so you constantly feel like you are the last line of defence between your kid and the lousy modern world.

You know, with total certainty, that a child is always better off with two good parents.

You know your child is scarred by his parents breaking up, and will carry those scars forever.

You feel like a freak at the school gates, because the world is full of happy, unbroken families.

And our ex can come barging back into your life whenever they feel like it, just by uttering the magic words – ‘This is my child too.’

But what did I know about it?

I had not been a single parent for years.

What made me such an expert?

It had been ten years since Pat and I had lived alone – that strange, messy period between my first marriage and my second. A time of raw pain all round, and being unable to wash his hair without both of us having a nervous breakdown, and the slow realisation of how much I had relied on Gina to give shape to my life, and form to our family, and to wash our child’s hair and put him to bed while I heard their laughter through the walls.

And what I remembered most of all about that time was the feeling that I had failed. I could still taste it, ten years down the line. The feeling of failure, as undeniable as a broken arm – failed as a father, failed as a husband, failed as a man. Lugging that feeling of failure to the supermarket, to the school gates, to the house of my parents – that’s what I remembered most of all. Failed as a son.

But it was all years ago. And although I still noticed the single parents at the school gates – their time much tighter, their love somehow fiercer and more protective and more evident – I could not pretend that I was one of their number.

I had a wife and three children. And they were our children. And if you wanted to be picky, and prissy, and small-hearted, then you could say that the boy was my son and the older girl was her daughter and the seven-year-old was our daughter together.

But we did not think that way.

The whole menagerie had been mixed up for so long – for most of the lives of the elder two, and for all of the life of the youngest – so that we did not think in those terms. Sociologists and commentators and politicians – they think in terms of blended families. In the real world, you just get on with it, and it either works or it doesn’t.

It worked for us.

This little post-nuclear family where the females out-numbered the males. It was home. But seeing Gina again had prised open some secret chamber in my heart where I still felt like the father I had been so long ago.

A card-carrying single parent.

Gina made me see that bitter truth.

Once a single parent, always a single parent.

‘The whites are worse than the darkies,’ Ken Grimwood said, and I did not know where to begin.

He was a time capsule containing everything that was rotten about the country I grew up in. Yet I found myself feeling curiously grateful that he was enlightened enough to see that the morality had little to do with the colour of your skin. But the casual talk of darkies – it gave me exactly the feeling of dread that I felt when I saw him producing his tin of tobacco and packet of Rizlas, which he was doing right at this moment. I felt like opening all the windows.

‘Please, could you save it until I’ve got you home?’ I said. His home was only in another corner of North London. But it felt like another planet, another century.

‘At least the darkies have God and church,’ he said, carrying on as if an audience had asked him to elaborate on his feelings about race relations in modern Britain. The roll-ups and the baccy tin sat in his lap, apparently forgotten. ‘God and church keep them in line. Nothing wrong with a fear of hell. Nothing wrong with believing you’re going to burn in the eternal fires of hell if you step out of line.’

‘I agree,’ I said. ‘It’s very healthy.’

‘As long as their God doesn’t tell them to stick a rucksack full of Semtex on the Circle Line,’ he said.

I looked at him and shook my head. ‘How can you talk like that?’

‘Like what?’

‘All this stuff about darkies,’ I said. ‘You fought against all of that, didn’t you? When the Nazis were building factories to kill people. You were fighting for tolerance. For freedom.’

He smiled. ‘I fought for your dad,’ he said. ‘I fought for my mates. For them. Not for King and country or anything else. We fought for each other.’

I kept my eyes on the road. Where was his son? Where was his daughter? They had never called back. Didn’t they love their father? Shouldn’t they be doing this chore, instead of Harry’s Magic Taxis?

He was looking out the window. The twenty-four-hour shops were lit up like prison camps. And I remembered how my mother and father would look at those same streets, the streets of London where they grew up. The look that said, There must be something out there I still recognise. ‘But the whites – what have they got? Cheap booze and talent shows and benefits,’ the old man said, looking at me sternly, as if I had just disagreed with him.

‘What’s the knife for?’ I said. ‘I can’t believe it’s just for sticking in your leg.’

‘Dogs,’ he said. ‘The knife is for dogs. Where I live, there’s a lot of big dumb animals – and some of them own very large dogs. The kind of dog that gets a kiddy in its cakehole and doesn’t let go. You can’t pull them off. Do you think you can pull them off? You can’t. That’s what the knife is for, smart arse. If a dog gets a kiddy.’

‘What did you do?’ I said. ‘What was your job?’

‘Print,’ he said, cramming sixty years of working life into one syllable. ‘That ended.’ He laughed. ‘The welfare state was built for men like your father,’ he said, and then his eyes shone with a sudden flare of anger. ‘Gift of a grateful nation. It was meant to be an effing safety net for the needy – not an effing comfy sofa for the effing feckless. Men – like your dad and me.’

Except that my dad would never have said effing three times in the same sentence. That was the big difference between my old man and this old man. I glanced at him and saw him staring out at the city streets, shaking his head.

‘Where did England go?’ said Ken Grimwood.

‘You’re looking at it,’ I replied.

‘This country’s finished,’ he said. ‘Land fit for heroes? They told us we were heroes and then they made us crawl. Told us we were heroes and then they made us crawl! More like a land fit for yobs and scroungers and anyone who just jumped off the banana boat…’

‘Then why stay?’ I said, cheerfully rising to the bait. I had argued like this before. It was like Sunday dinner with Dad.

‘I wanted to go,’ the old man said, with that same hard, resentful certainty that my father could summon up so easily. ‘Fifty year ago. To Australia. That’s the place. Got a son out there. Wanted to go myself. We were going to be ten-pound Poms. You went on the boat. Took bloody ages. We had been down to Australia House. Filled in all the forms and everything.’

‘What happened?’

‘My wife,’ he said. ‘My Dot.’ He smiled, thinking about his dead wife. ‘In the end she wouldn’t leave her mum.’ Then his voice went flat and hard. ‘So we stayed.’

‘I think they may have one or two immigrants in Australia,’ I said. ‘In fact, now I come to think of it, the entire country is made up of immigrants.’

‘That’s just where you’re wrong,’ he said, and he looked out at the grimy streets of King’s Cross but he was seeing Bondi Beach. ‘And I fancied seeing the penguins. I always wanted to see that. The penguins on Phillip Island near Melbourne. Thousands and thousands of the little buggers. They come out of the sea when it gets dark. On Summerland Beach. Every night of the year. I always fancied seeing that. What a sight it must be – all the penguins on Summerland Beach.’

‘Penguins?’ I said. ‘In Australia?’

He stared at me thoughtfully.

‘Exactly how little do you know?’ he said.

The dog was on me as soon as I got out of my car.

A rocket of muscle and teeth and bulging eyes, bounding up on my chest, pushing me back against the car, growling as though it had a human bone lodged somewhere deep in its throat.

Two men were milling around outside the flats. They were not kids with hooded tops that covered their faces and baggy jeans that did not cover their backsides. They were men around my age who had been losing hair and gaining weight for twenty years, so that now they resembled a pair of giant boiled eggs. I could see them tearing up the terraces in their number one crops two decades ago. They were old but they were not exactly adult. They were Old Lads. They looked up at me with their blank white faces. And they smiled.

Ken was ambling across the courtyard, fumbling with his keys. I tried to follow him and the dog shoved me back against the car with an outraged snarl. I looked up at the Old Lads.

‘He likes you,’ one of them said, and they both had a giggle at that. ‘Tyson likes you, mate. If Tyson didn’t like you he would have ripped your face off by now. You should be flattered, mate.’

And he did like me. I could tell by the way he suddenly settled down with his hindquarters wrapped around one of my legs. The growling subsided to a romantic moan.

I tore myself away, the vicious creature whimpering with frustration, and ran after Ken. He had paused halfway up the stairs.

‘Just taking a breather,’ he said, and I remembered how, near the end of his life, every breath my father took had been an effort. I stared down at the courtyard that the low-rise council flats overlooked. The Old Lads were shuffling off, the dog snarling and snorting around their snow-white trainers.

‘They should keep that thing on a lead,’ I said.

Ken began to get up. I took his arm and helped him the rest of the way.

‘They love their dogs round here,’ he said. ‘Big animal lovers, they are. Those two charmers are in the flat above me. With their old mum. They love their mum and their mutt, but not much else, as far as I can fathom.’

We had reached the first-floor landing. He had his keys in his hand, outside a green door that appeared to be made of cardboard. I could hear what sounded like a hundred television sets. I wasn’t used to it. All these people living on top of you.

‘Thanks for the lift,’ he said. ‘Fancy a cup of tea before you shoot off?’

I wanted to get out of here. But I looked down at the courtyard and the Old Lads were still mooching around with their killer dog. They strolled around the double-parked cars as if they owned all they surveyed, their giant bald noggins like twin moons. It looked like a car park in hell.

So I found myself following Ken inside. His flat seemed far too tiny to be the final stop in a lifetime. On the wall was a framed poster of a blonde girl on a white beach. Australia, it said. What are you waiting for?

There were photos on the mantelpiece. In black and white, a sailor and his bride. Also in black and white, a boxer posing for the camera, trying not to smile. The young Ken Grimwood, fists in a southpaw stance, a glint in his eye, his stomach like a washboard. And in faded colour, three smiling children in the sixties. Two boys and a girl, grinning on the doorstep of a caravan.

‘Good to be home,’ coughed Ken. ‘Take a pew while I put the kettle on.’

I sank into an orange sofa made of some synthetic material that must have seemed modern in the 1950s and now was just a fire hazard. On the coffee table was a copy of the Racing Post. The sofa seemed to suck me into its polyester heart.

The telephone rang. Ken was banging around in a kitchen the size of a coffin, busy with our tea. The phone kept ringing. I picked it up.

‘Dad?’

A woman’s voice. The daughter in Brighton. Tracey.

‘I’ll get him,’ I said, and when she wanted to know who I was, I told her. No apology for not calling me back. No thanks to Harry’s Magic Taxis for bringing him home from the hospital.

‘Is he all right?’ she said.

I looked at the phone. ‘He’s dying,’ I said.

Ken came back into the room with two mugs of tea on a tray. There was the damp squib of a roll-up glowing between his lips.

‘I know he’s dying,’ she snapped, as if I was the idiot home help. ‘I mean, apart from that.’

‘Apart from the dying? Oh, apart from that, he’s great.’

I heard the woman bristling with irritation. ‘He’s not still smoking, is he?’ Then her voice choked and broke. ‘Oh, that impossible old man.’

Ken smiled at me and bent to place the tea on the coffee table. When he had straightened up – it took a while – he took the phone from me. I could hear the voice of his daughter. He didn’t say much.

‘Yes…no…yes, as it happens…no, as it happens.’

He winked at me as he took a long toke on his cigarette and I looked away. I had already decided that I didn’t like her very much.

But she was right.

He was an impossible old man.

‘She wants a word,’ Ken said, handing me back the phone. The daughter’s voice was shrill with hysteria in my ear.

‘I just can’t believe you’re letting him smoke,’ she said. ‘What’s wrong with you?’

Then she hung up. Ken was laughing to himself.

‘I was married to her mother for near on fifty year,’ he said. ‘Her and that useless git she married managed about forty-five minutes. And they had a couple of kiddies too. So how come she’s the one dishing out advice?’

I sipped my tea. It was scalding hot, but I tried to bolt it down, despite the third-degree burns. I wanted to get out of there.

Ken took off his glasses, picked up the Racing Post and squinted at it with his mole-like eyes while patting the pockets of his blazer. He peered blindly around the room and for the first time I thought I saw a touch of fear on Ken Grimwood’s face.

‘Me reading glasses,’ he said. ‘Didn’t leave them at the hospital, did I?’

He made a move to rise but I held up a hand. Life’s too short, I thought, and began searching for his missing reading glasses. The dead air of old smoke stung my eyes and made me want to go home. The doorbell rang and I let him get it. I would find his glasses and then I would leave.

‘Try the chest of drawers,’ he advised, lumbering to the door.

I opened the drawer and rifled through old bills, a pension book, curling postcards from Down Under.

And a rectangular, claret-coloured box that I recognised from long ago and far away. It was about the size of a palm-held phone. The reading glasses were next to it, on top of a stack of prehistoric betting slips. There were voices at the door.

I looked up and saw Ken letting in another old man. Even smaller than him, and some kind of Asian. His skin was the colour of gold. He was old, maybe only slightly younger than Ken, but his face was curiously unlined by time.

I looked back at the box. I picked it up. As the two old men shuffled into the flat, Ken doing all the muttering, I opened it.

And I looked at Ken Grimwood’s Victoria Cross.

I felt a stab of – what? Jealousy certainly – my dad’s DSM was the second highest award for bravery. The VC trumped that, and the lot. And I felt shock. And shame. It all hit me at once, as real as a kick in the stomach.

I had never seen one before. I had held my father’s Distinguished Service Medal a million times, but I had never seen one of these. FOR VALOUR it said on a semi-circular scroll, under the lion and the crown. The medal was suspended by a ring from a suspension bar of laurel leaves. The ribbon was pale pink, but I suppose it could have faded with time. I closed the box and shut the drawer. Then I opened it again and took out the reading glasses.

‘This is Paddy Silver’s boy,’ Ken was saying to the golden old man. Ken was smiling. The other old boy watched me without expression. ‘He passed away,’ Ken said, and his friend looked at him quickly. Ken smiled and nodded. ‘Ten year ago. More. Same as I’ve got. Cancer of the lung.’

The other old man nodded once, and looked back at me.

‘This here’s Singe Rana,’ Ken said. ‘His mob were at Monte Cassino with our mob. Did you know that? Did you know the Gurkhas were with our lot in Italy?’

I shook my head.

‘I didn’t know that,’ I said, and I held out my hand to Singe Rana.

He shook it, a handshake as soft as a child’s.

‘Nobody knows anything these days,’ Ken said. ‘Nobody knows bugger all. That’s the problem with this country.’ He looked at his friend. ‘Wanted him to march with us, didn’t we? Paddy Silver. March at the Cenotaph.’

Singe Rana confirmed this with a curt nod. If he was upset about my father’s death, he gave no sign. But of course it was all a long time ago. All of it.

‘But he was never much of a marcher, your old man,’ Ken said. ‘He was never one for wearing the beret and doing the marching and putting on the medals. But we thought he could come down there. And if he didn’t fancy a march, well, then he could just watch.’

He looked at Singe Rana.

The old Gurkha shrugged.

I handed Ken his reading glasses.

‘I’ll come,’ I said. ‘I’ll come with my son.’

When I was twenty-five years old, and about to become a father for the first time, my mother told me the same thing again and again.

‘As soon as you’re a parent,’ she said, ‘your life is not your own.’

What she meant was, Put away those records by The Smiths. What she meant was, Wake up. The careless freedom of your life before there was a pushchair in the hall is about to come to an end.

But I never really felt that way. Yes, of course everything was changed by the birth of our baby boy – but I never felt as though I had surrendered my life. I never felt as though parenthood was holding me hostage. I never felt that my life was not my own.

Not until that night I waited for Pat to come home from Gina’s place in Soho. Not until he was absent and I was waiting. Then I really felt it, manifesting itself as a low-level nausea in the pit of my stomach, and nerve ends that jangled at every passing car. Finally, I understood.

My life was not my own.

The sound of Joni came down the child monitor and Cyd tossed aside her Vogue. ‘I knew it,’ she said. ‘Dr Who always gives her nightmares.’

‘It’s the Weeping Angels,’ I said. ‘They give me nightmares, those Weeping Angels.’

‘I’ll lie down with her for a bit,’ Cyd said. ‘Until she settles.’ She stroked the top of my arm. ‘I’m sure he’s fine,’ she said.

It was near midnight when Gina’s taxi pulled up outside. She didn’t get out but waited until he had opened the front door before driving away. He came into the living room, his face a mask.

‘You all right?’ I said, keeping it as light as I could.

He nodded. ‘Fine.’ Not looking at me.

‘Everything go okay?’

He was fussing with his school rucksack, checking for something inside.

‘I’m going back next week,’ he said evenly. ‘Gina asked me to go back next week.’

He still wasn’t looking at me. ‘Well, that’s good. That’s great.’ Then I thought of something else. ‘You take your pills?’

He shot me a furious look. ‘You don’t have to remind me,’ he said. ‘I’m not a baby.’

He had to take these pills.

A few years ago, just at the start of big school, he had been laid flat by what looked like flu at first and, after he had missed most of the first half-term, began to look horribly like ME. We found out, just after one of the less fun-packed Christmas celebrations, that he had a thyroid condition. So he took these pills and they made him well. But he would have to take them every day for the rest of his life. There are children all over the world who have to deal with a lot worse than that.

But I went to bed knowing that I would be wound too tight to sleep tonight, or at least until it was nearly time to get up.

Because that was another thing that Gina had missed.

Five

Tyson saw me as soon as I got out of the car.

At first he just stared – ears back, teeth bared, a long stream of drool coming out of the corner of his vicious maw. As if he couldn’t quite believe his luck. The object of his base lust had returned.

Then suddenly he left the side of his Old Lad masters, their huge boiled-egg heads leaning together in hideous fraternity, and bounded across the courtyard, weaving between the brand-new Mercs and rusty jalopies with Polish plates.

Too late.

By then I was halfway up the concrete staircase, already hearing the whine of the dusty wind that whistled down the corridors of Nelson Mansions.

I banged on the old man’s door.

It took him an agonisingly long time to open, but I was inside the trapped air of his flat before Tyson arrived. We could hear his meaty paws slapping against the thin door as he howled of his unnatural love.

Singe Rana was sitting on the orange sofa, watching the racing. He glanced over at me, made a small gesture with his impassive face and turned back to the 2.20 at Chepstow.

‘I brought you these,’ I said, and gave Ken the A4 envelope I was carrying.

He reached inside and took out a handful of black-and-white photographs, pushing his face against them. I found his reading glasses and gave them to him. He took the photographs over to the sofa and I stood behind the two old men as they leafed through them. They picked up the first one.

It could have been a holiday photograph. There were perhaps a dozen young men, tanned and hard, posing in the sunshine on the deck of a ship.

‘On the way to North Africa,’ Ken said.

‘That was lovely trip,’ said Singe, and his Nepalese accent had a soft Indian lilt to it. He smiled at the memory. ‘There were dolphins swimming and flying fish used to flap about on the deck of our landing craft. We saw a whale and her children.’