The Genius in my Basement

He taps his china cup of elderflower irritably.

‘All I can say is that since our mother died, Simon’s become a different person. I noticed that almost immediately. He’s got more sociable. When he comes to dinner, he’s much more at ease. Instead of sitting in a corner reading a book as he did when she was alive, he joins in. I’ve bought him three clean shirts which hang in a wardrobe here, for him to pick up whenever he comes to London.

‘I think my biggest triumph is persuading him to get rid of his money. Did you know, he gives £10,000 a year to campaign against cars?’

Francis Norton, Simon’s middle brother, works here …

… in a jewellery shop.

Francis brings in the family money. The company, founded by Simon’s great-grandfather, is the oldest family-run antique jewellery business in the world, patronised by the Queen, pop stars, fringe aristocracy, footballers (if they know what they’re about) and all London people with 100-acre second homes in Wiltshire.

Ten years before Simon was born, S.J. Phillips established itself as the epitome of Englishness by taking part in a famous wartime deception called Operation Mincemeat, later dramatised in the film The Man Who Never Was.

In April 1943, a Spanish fisherman discovered the decomposing corpse of a man floating off the coast of Andalusia. Documents on the body identified him as Major (Acting) William Martin of the Royal Marines. He was handcuffed to a briefcase, which contained a bunch of keys, an expired military pass, two passionate love letters, a picture of a woman in a swimming costume (‘Bill darling, don’t let them send you off into the blue the horrible way they do’), a £53 bill for an engagement ring and a letter from Lord Louis Mountbatten to General Alexander revealing the plans for the Allied invasion of Europe.

Spain, though neutral, supported a very efficient network of German agents. They soon found out about the drowned Marine, got hold of the briefcase and carefully extracted the top-secret letter from its envelope. The British had made the greatest intelligence blunder of the Second World War. With ample time to prepare his defences, Hitler now knew that the Allies were going to invade Europe through Sardinia and the Peloponnesus: the Germans transferred the 1st Panzer Division to Greece and started laying minefields.

It wasn’t until the British got the corpse of Major (Acting) Martin back, a fortnight later, that they knew the Nazis had definitely fallen for the trick. British Intelligence had folded the fake letter to Mountbatten only once before sliding Martin’s dead body into the sea from a submarine off the coast. When the body and effects were returned, investigators spotted under

Excerpt from an interview with Francis and his wife, Amanda

Amanda: When I met the Norton family, I thought they were all so bizarre.

Francis (nodding): My mother was very, very old-fashioned. It was, you know, ‘It’s four o’clock in the afternoon, you can go see your mother.’ We absolutely adored her.

Amanda: They were just so Victorian. I’d never met anything like it in my life.

Francis: My father always said his ideal was to have a tail-coated butler behind every chair.

Amanda: I’ve never known parents who were so unphysical. In the morning Helene, their mother, would go off and do her charity work, then come home and have a long cigarette, put on her kaftan for the afternoon, and sit there doing the crossword puzzle.

Francis: Terribly unfulfilled.

Amanda: I remember once – this is how old-fashioned they were – I’d just had my son Alexander, he was about nine months old, and Dick [Simon and Francis’s father] was standing there, with the table laid with all the silver, and Domingo the butler hovering around. And Dick looks at me and says, ‘Amanda, darling, has Alexander started masticating yet?’

a microscope that the letter had been carefully refolded, creating a second crease.

A month later, Britain and America began their assault 300 miles west of the location indicated in the letter, though Sicily.

S.J. Phillips, Simon’s family firm, provided the £53 engagement-ring bill – it was seen as the touch that the Germans would regard as unfakably, quintessentially English.

Francis is Simon’s saviour. It’s because Francis keeps the family firm alive and profitable that Simon has never had to have a job or a mortgage and, despite using seventeen different variants of bus, train and visitor-attraction discount cards, doesn’t actually need a single one of them.

A mild, self-effacing, apparently undogmatic man (I’ve met him only twice), Francis lives on the other side of Hampstead from brother Michael, and has the talcum-powder-dusted look of the very rich. He is an accomplished cellist.

Every year Francis or Michael invite Simon to their house for Passover; and every year Simon arrives with his shoelaces flapping, his holdall bulging, his bus timetables and his smells, and eats all the parsley.

Now, back to grunts.

The fifth type of grunt emitted by Simon is metaphorical – it’s not a guttural sound, it’s a full sentence. The mathematician Professor John Conway calls it a ‘Thank you, Simon’, defined as ‘a statement that is indubitably true, but the relevance of which is obscure’. For example, in the middle of a discussion with me about whether the Monster might in fact not be a large object at all, but something very small and everywhere, like a flea, Simon will burst out:

‘Incidentally, I was once going on a train and the conductor pronounced that we were now approaching “Manea, the centre of the universe”.’

What can you say after he’s said that? What does he mean? That the flea-Monster, which Simon suspects contains the solution to the symmetry of the universe, is living in Manea, a village in the Cambridgeshire Fens? It can’t be that. Simon is not a lunatic. Maybe it’s just the word, ‘universe’. But he clearly expects some sort of reply. So, after a suitable pause, you murmur, with a slight doff of the head,

‘Thank you, Simon.’

Then you attempt to pick up the pieces of the shattered conversation.

It’s important to realise that this fifth type of grunt never comes about because Simon isn’t able to keep up with the discussion, or because his brain has short-circuited and popped out the non-sequitur in a fizz of misfired neurons. They appear for the opposite reason: he has dashed too far ahead, gone off on a side path, left the ponderous, sequential-talking rest of us behind, raced up into the hills of puns and synonyms and humorous, leapingly interconnected memories … then jumped back with the result, waving his arms and grinning in triumph, like a child ambushing us from behind a tree.

As the fact dawns on Simon that no one has the foggiest idea what he’s talking about, he is not resentful. Politely, he allows the intensity of his grin to slip away. Measuredly, he rejoins the conversation.

(1) Happy, (2) puzzled, (3) incomprehensible, (4) frustrated, (5) phrasal (‘Thank you, Simons’). Sometimes, Simon will go for weeks without offering anything to his biographer but one of these five grunts.

And then, PING!

An email comes.

And behind the grunts, a man.

Monday, February 8th, 9.19pm

I’m sorry, I can’t make head or tail of the last chapter you sent me. I think that any reader who shares my way of thinking will be completely bewildered.

Tuesday, February 9th, 1.17am

I can’t follow the thread of your writing. If I were someone I didn’t know rather than myself, I suspect that in reading it I would have problems following the story even if I could understand the sentences. Incidentally, this is not something I’d say with your previous book. There I could understand your description of Stuart, my problem was you gave me no motivation to understand his character.

Wednesday, February 10th, 12.32am

I’m not sure what you mean [in Chapter 10] by my ‘jocular’ attitude to mathematics, but never mind. You’ve got the calculations wrong – 28 is 256, not 4096, which is 212, and the others are similarly shifted. I don’t understand your bit about numbers floating in the sky. No, I haven’t a clue whether it was a right or left leg that the duck was missing.

[This is followed by fifty-two lines explaining the story of the legless duck, which also includes a self-playing piano, an inferno in the Channel Tunnel, admission that he reads a magazine called Cruising Monthly, and a threat of imprisonment by gas inspectors.]

Wednesday, February 10th, 12.48am

I know what the word ‘jocular’ means. What I don’t know is what you mean when you describe my love of mathematics as jocular, I might be jocular, but how can my love of mathematics be? I don’t know what you mean by a ‘Rabelaisian’ series (and don’t say ‘in the style of Rabelais’!). However, unlike you I do know how to spell the word.

eSimon, the Simon who logs on to his computer at one in the morning, is a different man to Simon the grunter: eloquent, fluent, conversational, reflective, poignant, sometimes funny and – if the subject matter has anything to do with my attempts to understand genius, popularise mathematics or write biography – acerbic.

Simon’s interview with Kevin, resident of Cambourne, in 2016 (An example of Simon’s clear, fluent, amusing writing style. Abridged from an editorial (2006) in his Public Transport Newsletter, which he writes and publishes three or four times a year.)

Q: What decided you to move to Cambourne (a village outside Cambridge)?

A: We chose Cambourne because there was a direct bus link to my job in Papworth, and we could also get buses to St Neots for trains to London. It also seemed a good place for my wife’s ageing parents. And we hoped our house would be a good investment – its value would have gone up had the east–west rail link been built close to the A428, as recommended by the London-South Midlands Multi-Modal Study.

Q: But I gather things then went sour.

A: Yes. In 2005 the bus links to Papworth and St Neots were reduced, and I found I had to cycle in most days. The main road was very unpleasant, and the side route via Elsworth took twice as long. Then in 2006 came the Council’s budget cuts to buses. In 2007 the A428 dual carriageway opened, our road became an ‘overspill A14’, and Madingley Road became clogged, making our buses increasingly erratic.

Q: But things are better now, aren’t they?

A: Yes, in one sense. The big stores left the city centre because they realised people didn’t want to have to put up with gridlock every time they went shopping. But there’s the downside that it’s now much harder to get to the shops by public transport. Nor could we use internet shopping as there was rarely anyone in the house to accept deliveries, apart from my mother-in-law who was often asleep, and even when she was awake she could never get to the door on time.

Q: How have your family been coping?

A: My father-in-law died in the bird flu epidemic. My mother-in-law has become increasingly frail. Visiting the children in Oxford and London is a problem – the bus to Oxford has been taking ever longer because of growing congestion, and it’s a long walk from the city centre to the rail station. For a time we tried the coach, but then they moved the coach terminal to the rail station too …

Q: Have you ever thought of buying a car?

A: Yes, often. But then we’d ask, how could we face our children knowing we’d helped to ruin the world for them? Our generation has badly betrayed our children’s.

Q: I gather you’re leaving Cambourne soon?

A: Yes, we’ll move to London or Oxford as soon as we’ve settled on a place for my mother-in-law. Good riddance – to the Cambridge area I mean, of course!

see www.cambsbettertransport.org.uk/newsletter93.html for the full version.

10 Mars

People do sometimes tell me how nice I am looking (e.g. at my mother’s funeral) when I wear new clothes, but it always makes me feel very embarrassed. I say, ‘I don’t want to know that.’ I don’t want to be thought of as someone for whom personal appearance is important.

Simon

‘I’m going to see a Martian. He aaah, hnnn … it lives in Woking.’

Simon blocked my sun, his holdall swinging slowly to a stop after his unexpected rush off the pavement at my café table.

‘Hnnn, aaah, uugh. As I say, my grandmother lived where the Martian is. Hnnnh. Would you like to come too?’ Spring on earth! Simon giving me encouragement!

I jumped up, swigged back my coffee and gathered my books and notes. A ballyhoo of cherry blossom leapt about the wall of Darwin College Fellows’ Garden. Dead-looking trees creaked out of the sodden grass, sprouted buds and crackled quickly into the sky.

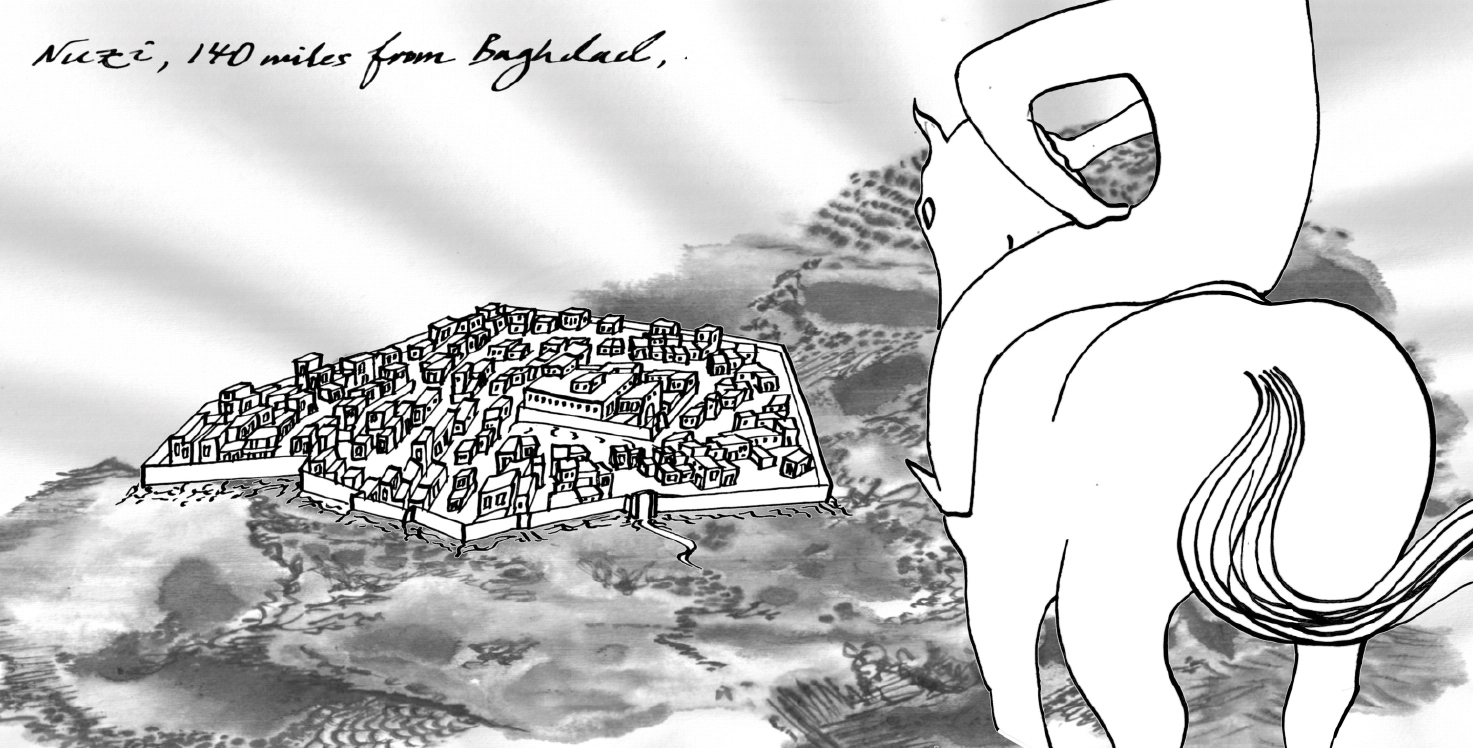

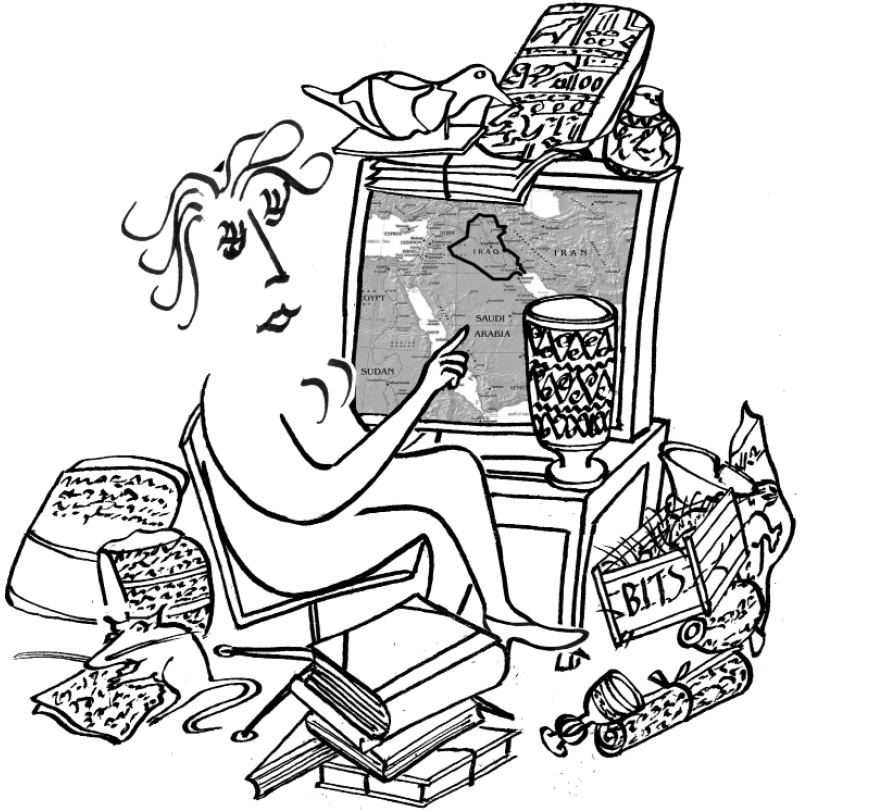

I’d been working on a cartoon about the origin of numbers.

In the late 1970s a young French woman called Denise Schmandt-Berserat made an astonishing discovery. Forgotten in the storeroom of the Fogg Museum of Art in Harvard

was a prehistoric clay purse

from the ancient city of Nuzi,

in the country now called

Iraq.

‘Uuuugh, aah, errr … oh dear!’ Simon blustered. ‘What is the point of this? I don’t understand pictures.’

‘It’s the origin of your subject. The purse had an inscription on it that said it was the property of Ziqarru, a shepherd, and contained forty-nine “counters representing small cattle”. Not that that impressed the Harvard excavators any more than it does you. They broke the seal, found the forty-nine clay pebbles inside, as promised – and lost them.’

‘Oh, dear.’

‘Exactly. But this French scholar realised that Ziqarru’s egg-shaped purse was a simple accounting device, from the dawn of writing. People had discovered other egg-shaped purses containing counters before, but none with symbols on the outside like this. It was the earliest known attempt to symbolise the contents of the purse with abstract marks. According to her, it was the need, by palace accountants, to keep track of animal numbers that led to the invention of writing and mathematics. If someone who understood the new marks thought Ziqarru had been stealing animals, all they had to do was check the writing on the outside. And if Ziqarru suspected that person of using the newfangled cuneiform to cheat him, he could break open the purse and prove he was innocent by counting the flock off against the pebbles inside. Lo! Symbolic writing had begun. Next thing you know, it’s algebra, calculus and Shakespeare. Writing comes from mathematics, in short, and it all comes from accountancy.’

‘Oh, DEAR!’

‘Why “Oh dear!” this time?’

‘No reason,’ sighed Simon morosely, and unbent his elbow.

The handles of his holdall rippled down the forearm of his puffa jacket and the bag dropped to the pavement.

‘Excuse me!’ he gnashed. ‘I’d like to sit down. Can you remove all this paper?’ As he hit the seat he jolted into a better temper.

Simon’s most famous ancestor was the Prophet Abraham, of Ur of the Chaldees. Then came Joseph, of the Coat of Many Colours. His son was Manasseh, first mentioned in Genesis, who led one of the twelve tribes of Israel. Next follows 3,000 years of forgetfulness before the family pops back into life on a rolled-up poster in the back room of Simon’s Excavation – two shelves along and one up from the television-that-might-have-broken-twenty-years-ago-but-possibly-it’s-only-a-fuse:

ASLAN MANASSEH

b. Bombay 1884

m

KITTY MEYER

b. Calcutta 1891

The Manassehs are the leading family of the oldest settled community of people in recorded history: the Iraqi Jews of Babylon, 150 miles from Nuzi and Ziqarru’s purse.

Congratulating myself on my willingness to be at the coalface of biographical reportage and, at a moment’s notice, drop everything and go to Woking, I walked with Simon from the café, across the park . ‘The Martian’ turned out to be a statue in honour of H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds. According to a tourist leaflet Simon eventually discovered in his coat pocket, it’s seven metres high. It looks like a beetle trying to curtsey with its legs stuck in vacuum tubes. There’s also a Woking Spaceship embedded in the pavement nearby, and Woking Bacteria, made out of splodges of coloured concrete brick.

Battling a wallet from his trousers pocket, in the centre of Cambridge Simon boarded a bus to the railway station. He muttered out coins into the driver’s cash tray, seized the ticket, held it to the light to investigate it with narrowed eyes, then made for a free space at the back of the bus, bouncing his holdall from ear to ear of the seated passengers.

The woman in front’s face was soured by watchfulness. Simon, though sexless as a nematode, is the fantasy image of a kiddy-fiddler, and this Bruiser Mum had spent her morning proudly dressing up her six-year-old daughter in lash-thickening mascara, gloss lipstick, Primark miniskirt and pink heels.

Simon, blank-eyed, belly exposed, his ski jacket rucked halfway up to his chest, threw himself at the seat with a self-congratulatory sigh and let his face settle around his grin.

I stood beside him, took out a notebook, and consulted a list of urgent biographical questions. It is important, with Simon, to select not just the correct wording for a query – one that doesn’t contain any banned nouns or adjectives, or lead to outbursts of correction because of a tiny factual error – but also the right context. PHILOSOPHICAL questions are best on a Tuesday night. This is because he has returned from his weekend jaunt to Scarborough, via Glasgow, the Isle of Man and Pratt’s Bottom, finished his week’s backlog of 347 emails: he is feeling expansive and post-prandial. Questions requiring REMINISCENCE can be extended as far as Thursday, or broached on country walks through Iron Age hill forts – there is nothing quite like 2000-year-old battlements, where the clash of Roman legion against shrieking Celt still trembles in the air, to get Simon going on the subject of Ashdown, his junior school.

Bus trips to the train station are strictly for the exchange of FACTS.

The scholar of Simon Norton Studies must proceed with delicacy.

‘I wanted to ask about your grandfather, Aslan,’ I began. ‘He was a businessman, wasn’t he?’

‘If you say so.’

‘What did he sell?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘According to your brothers it was textiles, but what …’

‘Yesterday I was in Blickling.’ Simon pinched his fingers into his wallet and extracted a worm of paper. ‘Here’s the ticket.’

‘Simon, your grandfather. Was it jute?’

He waggled the ticket higher in the air, closer to my face. Four inches long, it had arrowhead shapes cut out at either end, and purple 1970s techno-writing along the length repeating with great mechanical urgency, top and bottom, that it was 1.23 p.m. in King’s Lynn, and that Sheldrake Travel was ‘very happy to have you aboard’.

(‘I do not think that could have been the ticket I showed you. There is no direct bus from King’s Lynn to Blickling. But if you prefer to get things wrong deliberately, you belong on the team of a trash publication like the National Enquirer.’)

‘Is there anything special about it?’ I asked, too self-conscious to hold the snippet of paper up to the light and try out his squinting trick, without at least some guarantee of reward.

Simon considered for a moment, then shook his head contentedly. ‘No.’

‘I was in Blickling last week, too,’ said a fellow sitting beside Simon. The man was resting his chin on his hands, which were in turn piled on the handle of his walking cane; he bounced his head gently. ‘Lovely hall, and, aaah, the lake. I got there very early and the mist, it was …’

‘Did you go on any buses?’ Simon blurted.

‘To the hall,’ agreed the man, nodding some more, rather slowly, as if tapping the sharpness out of the interruption.

‘From?’ shot Simon.

‘Norwich, I believe it …’

‘The number X5,’ Simon declared, and directed a smile of triumph around the bus.

The elderly man was not to be put off: he was a trouper for the cause of discursive memoir. ‘I think my favourite – I mean, lakes are always lovely, but lakes are lakes, I always say – my favourite was the Chinese Room. Did you see that? That flock wallpaper, it was flock, wasn’t it, and that pagoda in the glass cage …?’

‘Any other buses?’ interjected Simon bluntly.

‘Well, after lunch, we went to Cromer, and had the most delicious brown crab …’

‘The X5 again. Unless you went on a Sunday?’

‘No, let’s see, Tuesday, that’s it, because then at Wells-Next-the-Sea, the sunlight on the water was sparkling in just …’

‘Uggh, ah …’ Simon pulled out a dog-eared timetable from his bag and searched the pages. ‘Let’s see, aah … the 73.’ Spotting that Nodding Man still had a bit of life in him, Simon brought in the heavy artillery, lifted out a second book, which seemed to be compressed from the scrag ends of newspaper, ran his fingers down the index and began darting back and forth between two sections at once. ‘But you could have taken the 645 and changed at … let’s see, aaah … or, uuugh, aaaghhh, if you’d wanted to go on the steam railway …

(‘Alex! What are you saying? Number 73? Number 645? A steam train? I am sure you have invented these references also. I could not have said them. Do you want me to be seen as an ignoramus on public transport?’)

‘… which calls at hnnnn … King’s Lynn, and …’

It began to rain. First, a barely visible drizzle, picked out only against certain backgrounds – the black reflections in the windows of the Cambridge Hotel; a middle-distance blurriness when the bus stopped at the crossroads by the Catholic church, and we had a view up to the park. But it might have been nothing more than stripes of movement left in my eyes by the Clint Eastwood action smack-’em-blast-’em-ride-off-into-them-thar-cactus-lands flick I’d watched last night. Next, streaks of water on the window. Finally, drops pounding the metal sill by Simon’s elbow in buttercup explosions.

‘Getting back to your grandfather, Aslan …’

The driver slammed the brakes and swerved to avoid a line of Japanese girls who’d abruptly pedalled across the road in front. The bus was filled with sudden pushes and violent attempts to avoid falling over. I crashed forward down the aisle and fell sideways onto the six-year-old nympho.

‘Oi, watch where you’re fucking going,’ growled Bruiser Mum.

Simon, who spends much of his time smiling, smiled wider. He burrowed into his bag and, after much rustling and what looked like punches delivered at the fabric from the inside, re-emerged holding a carton of passionfruit juice, which he upended over his mouth.

At the end of the nineteenth century there were 50,000 Jews – a quarter of the city’s population – living peaceably alongside Arabs in Baghdad. Today, according to the latest web report, there are four – four in the entire city. The pro-Hitler Iraqi government expelled and murdered them in pogroms before and during the Second World War. In the late 1940s underground movements smuggled them to safety at the rate of 1,000 a month. In 1951, Israel airlifted 60,000 more from the whole of Iraq and, with the perversity of the self-justified, bombed the rest to try to persuade them to follow. There are today more ostriches in Baghdad than there are Jews.