The Genius in my Basement

On one edge of the genealogical poster I’d excavated in the basement is a dedicatory note about Simon’s family:

All probabilities and evidence go to suggest that this community is descended from the ancient Jewish communities settled in Mesopotamia since the days of the Babylonian Captivity, 2,600 years ago … The purpose, in compiling the genealogical table, is to preserve, in some way, a record of a section of this community

The very same day that Israel finally declared independence as a refuge for the most persecuted race on earth, Syria, Lebanon, Egypt, Jordan and Iraq launched a combined attack, which the Secretary of the Arab League declared on Cairo radio was ‘a war of extermination, and a momentous massacre which will be spoken of like the Mongolian massacres and the Crusades’.

‘Murder the Jews! Murder them all!’ shrieked the leading Islamic scholar of Jerusalem.

Sixty years later, a man in London offered a million pounds to any breeding Iraqi Jewish couple who would go out to Baghdad to repopulate the city. ‘I have a friend who’s interested,’ I enthused to Simon. ‘What do you think? Her name’s Samantha.’

‘I dislike the name Samantha, so anyone with that name would be unlikely to attract me. Maybe it’s because it makes me think of Samantha Fox, the pornography star … I may say, I do have a relation with a Samantha. She deals with my tax affairs.’

Simon settled into a dead-eyed stare, gave himself a hug with his elbows and went back to looking out of the window: a quiet, euphoric gesture. Until we were on the train, he could devote his entire attention to ignoring me.

Higher up Simon’s genealogical poster, closer to the rustle of the Old Testament, the children are nameless, lives are replaced by question marks, but deaths are biblical: a sister to Habebah, ‘drowned in the Euphrates’; Sassoon Aslan, ‘buried in Basra’; Minahem Aslan, ‘childless, in Jerusalem’. Before that, Simon’s family disappears off the top of the page into the Mesopotamian sand dunes.

At the train station, Simon jolted off the bus to the fast ticket machine in the concourse and pressed screen after screen of glowing virtual buttons. Once he’d finally amassed all our possible discounts, off-peak fares, and unexpected mid-journey changes to thwart the local train operators’ pricing structures, he stared for a minute at the screen, which was demanding to know how many passengers apart from himself were taking the trip.

‘0’ pressed Simon, and looked up at me without crossness or dismissal.

Together, Aslan and Kitty Manasseh had five children, spaced every two years: Maurice, whose wife sneaked off one day when he was out and had herself sterilised; Nina, an old maid; Lilian, who ended up ‘in Blanchard’s antique shop’ …

(‘Do you mean she was for sale, Simon?’ ‘No! Of course not, he, he he.’)

… in Winchester, childless; Helene, Simon’s mother (Gaia among women in that barren setting, because she had three boys); and Violet, a war widow, who added another boy. This man, Simon’s first cousin, goes by the name of David Battleaxe.

‘You mean he was christened that?’ I perked up.

‘Not christened, although we do celebrate Christmas. He’s Jewish. We’re all Jewish,’ replied Simon. We were on the train now, hurrying down the aisle.

‘David Battleaxe …?’

‘After a racehorse.’

‘A racehorse?’ I puffed.

‘In Calcutta.’

‘In Calcutta?’

‘One of my grandfather’s,’ said Simon, then lunged left and landed with a thump in a window seat, his bag arriving on his lap – crucccnchch – a split-second after.

‘So you do know something about your grandfather,’ I observed, squeezing past two beer cans into the rear-facing seat opposite, next to the toilet. ‘He kept racehorses and named his grandson after a stallion. Yet when I asked you what your grandfather did just now, you said you didn’t know.’

‘You asked me what he traded, and I said I didn’t remember.’

The train pulled away, clacked across various points until it found the London tracks, and mumbled past the Cityboy apartments with tin-can Juliet balconies.

‘I don’t think he did trade horses,’ resumed Simon, as we picked up speed towards the Gog Magog hills. ‘Therefore I did not feel that it was relevant to provide that as an answer.’

A conductor hurried up to us, clicking his puncher, jutting his chin across seat columns, and demanded tickets and railcards.

Simon had his wallet already prepared, bunched in his fist, and offered up his pass and all the other necessary pieces of coloured cardboard in a derangement of eagerness. So many, the man needed an extra hand to deal with it all: the outward from Cambridge to Wimbledon via Clapham Junction and Willesden Junction covered by one set of reduced-fare permits; a continued discount outward from Wimbledon to Woking, with ‘appropriate alternative documentation’. As the conductor sifted through these triumphs of cunning, Simon’s face was suffused with expectation. The man adopted a bored expression and punched whatever suited him with a machine that pinched the paper hard and left behind purple bumps. Simon snatched the pile back and studied the undulations with satisfaction.

Another cousin I’d noticed on the family tree was called ‘Bonewit’. This woman appears on the fecund side of the family. It’s difficult to count the tiny layers of type on that half of the poster: seven children to Joseph and Regina; eight to Isaac Shellim and Ammam; ten – no, twelve – wait, my finger’s too fat for the tiny letters, eleven – to Shima and Manasseh: Aaron, Hababah, Ezekiel, Benjamin, David, Hannah, Esther … a rat-a-tat from the Pentateuch. Fifteen kids! to Sarah and Moses David. By the time they got to Gretha Bonewit, their seed was worn out.

‘Bonewit?’ said Simon, interrupting. ‘“Wit” is Dutch for “white”. I’ve got a Dutch dictionary in here.’

As the train passed Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Simon’s attention swerved, to gout. Jolting his hand out of the foreign-dictionary sector of his holdall, he sank it back in six inches further along and two inches to the right, and extracted a scrunched-up Tesco bag containing tablets. Allopurinol, for gout; Voltarol, for swelling (though it’s bad for his kidneys); Atenolol for blood thinning. He washed a selection down with more passionfruit juice and returned to dictionary-hunting.

‘Simon, why have you got a Dutch dictionary?’

‘Why shouldn’t I have a Dutch dictionary?’

‘Do you have a Mongolian dictionary?’

‘No.’

‘Do you have a dictionary for roast chickens?’

‘No.’

‘Well, then, why a Dutch one?’

Simon’s mother, grandfather Aslan (far right) and Battleaxe.

‘Because,’ he honked, triumphant that the answer had got such assiduous courting, ‘I …’ But at this point he found the book in question and pulled it out. ‘Let’s see, aaaah, hnnnn, bonewit, bone, bon … ooh …’ – his eyes lit up – ‘… it means “ticket voucher”.’

Simon will rot his floorboards with bathwater, immure his kitchen surfaces in Mr Patak’s mixed pickle and hack his hair off with a kitchen knife, but he is never unkind to maps. Returning the dictionary, Simon burrowed a foot and a half to the left and cosseted out an Ordnance Survey ‘Landranger’. He shook it into a sail-sized billow of paper, then pressed it gently into manageable shape.

Outside, the rain was frenzied. It clattered against the roof and ran in urgent, buffeted streaks along the glass. The flat lands of Cambridgeshire swelled up into a wave of hills.

When I looked back at Simon, a banana had appeared in his hand.

‘Right, your granny. Why did she live in Woking, but your grandfather stayed in Calcutta?’

‘I have no idea.’ Simon looked up from his map and considered the point. ‘Isn’t that the sort of thing married couples do?’

‘Was there a huge argument?’

‘No, oh dear, I don’t know.’

‘Did he have a harem?’

‘Huuunh. Should he have?’

Ordinarily, I like to record all interviews, because it’s not just the words that count, but the hesitations and silences. But this opportunity had occurred without notice, and I didn’t have my voice recorder.

I decided ‘Hnnn’, ‘Uuugh’ and ‘Aaah’ should be noted as ‘H

‘OK. How about this: why did your ancestors leave Iraq for Calcutta in the first place?’

‘Oh, dear, no. No, no,’ Simon replied. ‘I can’t possibly remember that. A

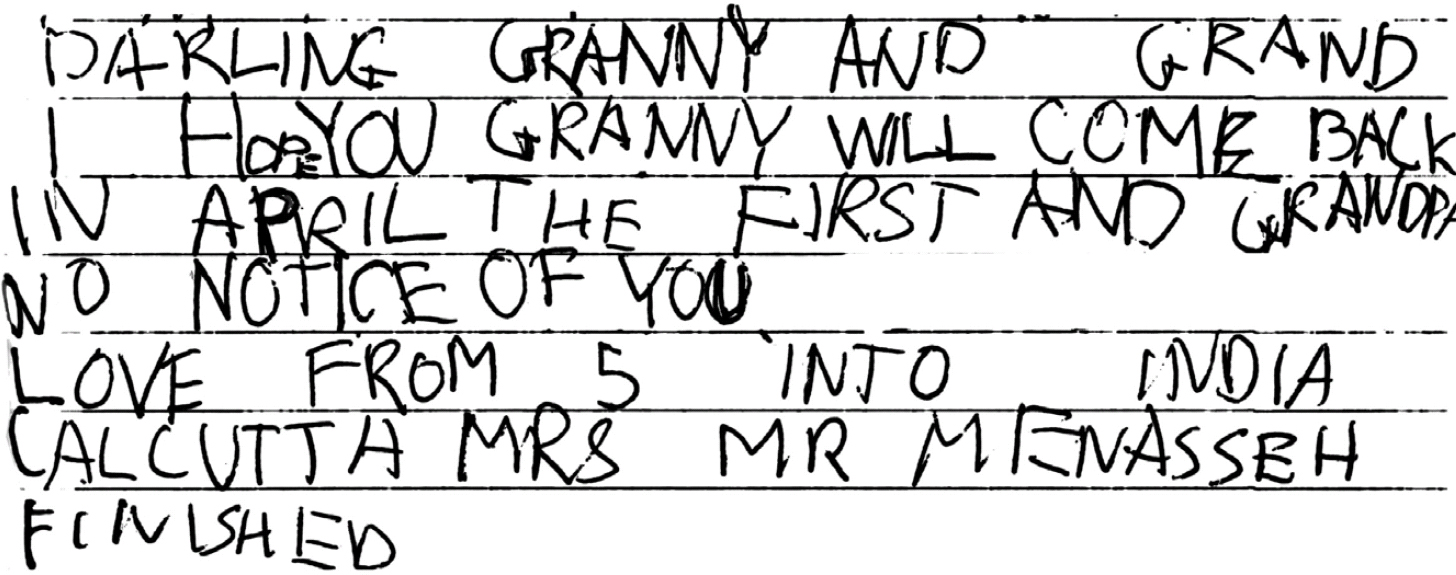

Letter to grandparents, from Simon (signing himself by number 5) aged 5.

In all of Simon’s recollections Kitty hobbles. After emigrating in the year he-doesn’t-know-when, leaving behind he-doesn’t-know-why her husband Aslan, she bought a he-doesn’t-know-what-type-of-house in Woking with a bamboo plantation.

‘Bamboo?’

Simon doesn’t-know-how – I mean, doesn’t know how – it got there. Every day, until her nineties, she dragged herself round, at first flicking gravel off the petunia bed with her walking stick; then, in her final stages of life, pruning the box-hedge parterre from her wheelchair, pushed by a daughter or a friendly guest.

‘One of her legs was broken,’ is Simon’s explanation for the hobble.

‘Permanently?’ I asked, and paused. ‘Which one?’

Simon thought carefully. ‘H

Another bout of concentration.

‘They alternated. Would you like some Bombay mix?’

Letter to his mother, aged 5.

When she wasn’t in the garden, Kitty sat in the front room overlooking the croquet lawn and played bridge. Her entire last thirty years seem to have been wasted on hobbling and cards.

Grandfather Aslan was ‘fairy-like’. Once every few years he appeared in London for a week, then disappeared. ‘Feeew-ff, just like that.’ The rest of the time he remained in Calcutta, the very successful dealer in … Simon still-doesn’t-know-what.

That’s it. There’s no point in prolonging this ancestral agony.

*11

Introducing

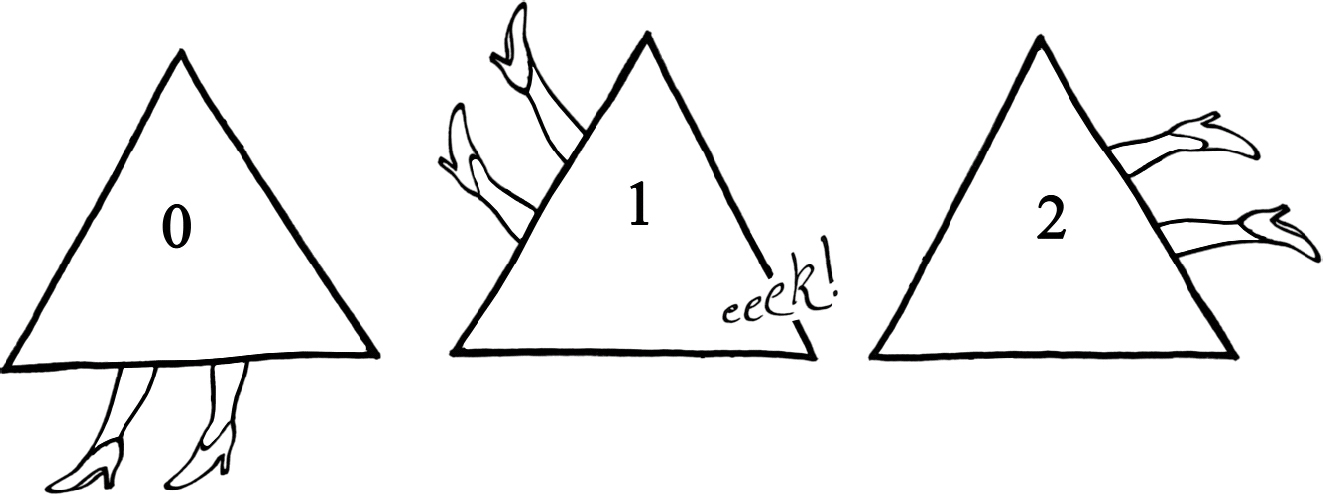

Just as a square can be rotated through four turns to get it back to where it was to begin with, and the results laid out in a Group Table, the same approach can be applied to every regular shape. The size of the table you need to draw depends on how many operations have to be performed before you’ve exhausted all the possibilities and ended up back where you started. An equal-sided triangle can be manhandled three times before it’s back on its feet:

As before, these represent the act of turning Triangle. The trick of the game is to find all the ways you can fiddle with Triangle and yet leave it looking just the same afterwards as it did before you began:

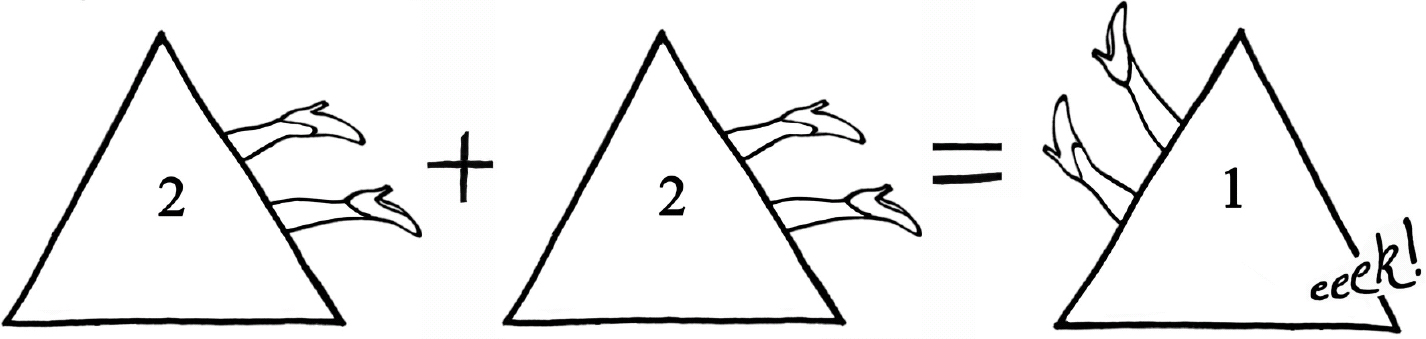

And (again as before, with Square) these turns combine in the most obvious way …

In words, turn Triangle once, then turn it again, and the result is two turns: one plus one equals two. It is easy to spin Triangle head over high-heels, if that’s what you want:

2 + 1 = 0

(two turns, followed by one turn, returns Triangle to its original position)

Remember, in Group Theory, turning a regular shape right round is taken to be the same as doing nothing at all. Full, completed turns don’t get totted up. It’s only the overall adjustment that matters:

2 + 2 = 1

The corresponding table (which, as with Square, looks like a pint-sized sudoku table) is therefore:

Once again, we’ve got through a mathematical section with a suspicious lack of awfulness, like someone who’s committed a crime in the woods.

Is that all there is to it? Was that really mathematics?

The mist in these woods is hushed. A distant leaf clatters among the branches like a falling pin.

Let it be whispered: a saucy chapter is approaching.

12

I had a camera once. When I found it wasn’t working, I had a sigh of relief.

Simon

The name ‘Norton’ is a fake. Simon’s paternal grandparents, from Germany, died before he was born – ‘No Nazis involved.’ His paternal grandfather anglicised the name from Neuhofer – i.e. New Towner, usually turned into Newton – then fiddled the result to sound less desperate. The only thing we can say for certain about these people, Simon pronounces sententiously, ‘is that when the surname was being used in Germany, the one place the Neuhofers did not live was in any village called Neuhof’. Then he sits back and stares at me happily, waiting for understanding to dawn.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Всего 10 форматов