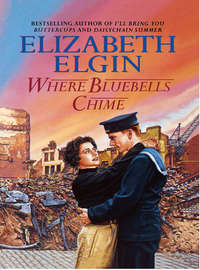

Where Bluebells Chime

‘That you, love?’ He half turned as the back door opened and shut.

‘It’s me, Dada. Mam not home, yet?’

‘No, lass. She rang up from the village, summat about getting the loan of a tea urn. Be about half an hour, she said.’

‘I’d better see to the blackout, then. Won’t take me long, then I’ll put the kettle on.’

Daisy had expected both her parents to be home; had got herself in the mood to come out with it, straight and to the point. That Mam still wasn’t back had thrown her.

She pulled the curtain over the front door then walked upstairs, drawing the thick black curtains over each window. She should have asked Dada, she brooded, how long ago Mam had phoned. She was getting more and more nervous. If Mam wasn’t soon home, she’d have to blurt her news out to Dada and she didn’t want to do that.

Mind, she was glad they had a telephone at last. They wouldn’t have got one if it hadn’t been for the coming of the Land Army, and them taking over Rowangarth bothy. Aunt Julia had been glad for the land girls to have the place because since the apprentices who lived there had been called up into the militia it had stood empty, and Polly living there alone, rattling round like a pea in a tin can.

The Land Army people had had so many requests from the local farmers for land girls to help out, and Rowangarth bothy would be ideal quarters for a dozen women. A warden would be installed to run the place and a cook, too. Aunt Julia had said they could have it for the duration with pleasure if they would consider Mrs Polly Purvis as warden or cook. Mrs Purvis had given stirling service, Aunt Julia stressed, looking after the garden apprentices, and would be ideally suited to either position.

So Keth’s mother was offered the cooking, and accepted gladly, especially when they’d mentioned how much wages she would be paid, as well as her bed and keep. And the GPO came to put the phone in.

That was when the engineer had asked Dada, Daisy recalled, why he didn’t get a phone at Keeper’s Cottage whilst they were in the area.

‘There’ll be a shortage of telephones before so very much longer, and that’s a fact,’ the GPO man said. ‘Soon you’ll not be able to get one for love nor money. The military’ll have taken the lot!’

Daisy could have hugged Dada when he said yes and now a shiny black telephone stood importantly in the front passage at Keeper’s Cottage.

For the first week, Mam had jumped a foot in the air every time it rang because Aunt Julia was tickled pink that Keeper’s was on the phone at last and rang every morning for a chat. And she, Daisy, so often sat on the bottom step of the stairs, gazing at it, willing it to ring so that when she lifted it and whispered ‘Holdenby 195’, Keth would be on the other end, calling from Kentucky and he’d say –

But Keth couldn’t call and she couldn’t call Keth, not even if she didn’t mind giving up a whole week’s wages just to talk to him for three minutes, because civilians weren’t allowed to ring America now. The under-sea cable was needed for more important things by the Government and the armed forces. Indeed, civilians were having a bad time all round, Daisy brooded. Asked not to travel on public transport unless their journey was really necessary; their food rationed, clothes so expensive in the shops that few could afford them, and no face cream nor powder nor lipstick to be had – even a shortage of razor blades, would you believe? But that was as nothing compared to what was soon to come, she thought as she pulled down the kitchen blind, drew together the blackout curtains then pulled across the bright, rose-printed curtains to cover them, because not for anything was she looking at those dreary black things night after night, Mam said.

‘Shall I make a drink of tea, Dada?’ Daisy switched on the light.

‘Best not, sweetheart. Wait till your mam gets back.’

Since tea was rationed six months ago, the caddy on the mantelshelf was strictly under Alice’s supervision.

‘Dada?’ Daisy sat down in the chair opposite. ‘There’s something –’ She stopped, biting on the words.

‘Aye, lass?’ Her father did not shift his gaze from the empty fireplace and it gave her the chance she needed to call a halt to what she had been about to say.

‘I – well, I know it’s stupid to ask, but can you tell me,’ she rushed on blindly, warming to her words, ‘what will happen to my money if the Germans invade us? Will I get it?’

‘Well, if you wait another year till you’re one-and-twenty, you’ll know, won’t you? Not long to go now, so I wouldn’t worry over much. But if you really want my opinion, that inheritance of yours is going to be the least of our worries if the Germans do get here. So let’s wait and see, shall us?’

Daisy’s inheritance. Money held in trust by solicitors in Winchester. Only a year to go and then it would be hers to claim, Tom brooded – if the Germans didn’t come, that was; if all of them lived another year.

‘Silly of me to ask.’ And silly to have almost blurted out what she had done yesterday, during her dinner hour. ‘You’re right, Dada. Either way now, it doesn’t matter.’

And it didn’t, when Drew was in the Navy and Keth was in Kentucky not able to get home, and people having to sleep in air-raid shelters and already such terrible losses by all the armed forces. When you thought about that, Daisy Dwerryhouse’s fortune was immoral, almost.

It came as a relief to hear the opening of the back door and her mother calling, ‘Only me …’

Then Mam, opening the kitchen door, hanging her coat on the peg behind it, patting her hair as she always did, popping a kiss on the top of Dada’s head like always.

‘Sorry I’m late, but I’d the offer of the use of a grand tea urn for the canteen. And talking of tea, set the tray, Daisy, there’s a love.’

She sat down in her chair, pulling off her shoes, wiggling her toes.

Then, as she put on her slippers Daisy said, ‘Mam, Dada, before we do anything – please – there’s something I’ve got to tell you …’

2

‘Tell us?’ Tom gazed into the empty fireplace, puffing on his pipe, reluctant to look at his daughter. ‘Important, is it?’ Which was a daft thing to ask when the tingling behind his nose told him it was. Loving his only child as he did, he knew her like the back of his own right hand.

‘Anything to do with the shop?’ Alice frowned.

‘Yes – and no. I don’t like working there, you know.’

‘But whyever not, lass?’ Tom shifted his eyes to the agitated face. ‘You’ve just had a rise without even asking for it.’

‘Never mind the rise – it’s still awful.’ Daisy looked down at her hands.

‘Oh, come now! Morris and Page is a lovely shop, and the assistants well-spoken and obliging. All the best people go there and it’s beautiful inside.’ Twice since her daughter went to work there, curiosity got the better of Alice and she had ventured in, treading carefully on the thick carpet, sniffing in the scent of opulence. She bought a tablet of lavender soap on the first occasion and a remnant of blue silk on the second. Paid far too much for both she’d reckoned, but the extravagance had been worth it if only to see what a nice place Daisy worked in.

‘I’ll grant you that, Mam. The shop is very nice, but once you are in the counting house where I work, there are no carpets – only lino on the floor. And we are crowded into one room with not enough windows in it. And as for those ladylike assistants – well, they’ve got Yorkshire accents like most folk. A lot of them put the posh on because it’s expected of them. And obliging? Well, they get commission on what they sell and they need it, too, because their wages are worse than mine!’

‘So what’s been happening? Something me and your dada wouldn’t like, is it?’

‘Something happened, Mam, but nothing that need worry anyone but me. Yesterday morning, if you must know. There was this customer came to the outside office, complaining that we’d overcharged her. She gets things on credit, then pays at the end of the month when the accounts are sent out. Anyway, yesterday morning she said she hadn’t had half the things on her bill, so I had to sort it out. She was really snotty; treated me like dirt when I showed her the sales dockets with her signature on them.’

‘But accounts are nothing to do with you, love. You’re a typist.’

‘I know, Mam, but the girl who should have seen to it is having time off because her young man is on leave from the Army, so there was only me to do it.’

‘So you told this customer where to get off, eh?’ Tom knew that flash-fire temper; knew it because she had inherited it from him.

‘As a matter of fact, I didn’t. I just glared back at her and she said I was stupid and she’d write to the manager about me, the stuck-up bitch!’

‘Now there’s no need for language!’ Alice snapped. ‘But if you didn’t answer back nor lose your temper, what’s all the fuss about?’

‘Oh, I did lose my temper, but I didn’t let that one see it. When she’d slammed off, I realized it was my dinner break, so I got out as fast as I could. She got me mad when there are so many awful things happening and all she could find to worry about was her pesky account!’

‘But you cooled down a bit in your dinner break?’

‘Well, that’s just it, you see.’ Daisy swallowed hard. No getting away from it, now. ‘I ate my sandwiches on a bench in the bus station, then I walked into the Labour Exchange and asked them for a form. And I filled it in. I’m changing my job. I’m not kowtowing any longer to the likes of that woman.’

‘And would you mind telling your mam and me just what that form you filled in was all about?’ The tingling behind Tom’s nose was still there. That little madam standing defiant on the hearth rug had done something stupid, he knew it. ‘You’re not going to work on munitions, are you?’

‘Oh, Daisy! Not munitions? Mary Strong went on munitions in the last war and went as yellow as saffron!’

‘Nothing like that, Mam, and anyway, they’ll probably not take me. You’ve got to have an uncle who’s a peer of the realm and a godfather who’s an admiral and your mam’s got to have danced with the Prince of Wales when she was a deb – or so they say.’

‘So what was it about?’

‘About the Navy. Drew has joined and I’m joining, too, if they’ll take me. The women’s navy, that is. The Wrens.’

‘You – are – what?’

‘I’m joining up.’

‘Oh, but you’re not! We could be invaded at any time! Just what do you think me and Mam would do if you were miles and miles away? You’ve got to stay here, safe at home!’

‘No! Drew is miles and miles away. Drew’s at Devonport – so what’s so special about me?’ Daisy challenged.

‘The fact that you’re still not of age, for one thing, and I don’t remember giving my permission for you to join anything,’ Tom flung, suddenly triumphant.

‘Oh but you did, Dada. Your signature was on the bottom of the form. I wrote it there for you!’

‘Why, you – you –’ His face took on an ugly red. ‘Don’t think you can –’

‘Tom! Stop it! Just take a deep breath, won’t you? Calm down, for goodness’ sake. That temper of yours is going to get you into trouble one day, just see if it doesn’t!’

‘I won’t have a bit of a lass forging my name!’ His voice was low; too low.

‘Well, she’s done it and I’m very annoyed about it. You’ll never again write your father’s name, do you hear me, Daisy?’

‘I won’t, Mam. And I’ve got to have a medical first, and they say there’s a waiting list to get in, so by the time they get around to me the invasion will have happened, if it’s going to. And I’m truly sorry, Mam, and oh – Dada …’

She threw her arms round her father’s neck and because he loved her unbearably he gathered her to him and stroked her hair and made little hushing sounds, just as he had always done when she was unhappy.

‘I’m a fool, aren’t I? I shouldn’t have done it but everything’s in such a mess. Drew has gone, and Bas and Kitty are in America, and Keth’s with them and –’ The tears came, then; great, jerking sobs from the deeps of her despair. ‘I miss Keth so much. The summer of ’forty he said he’d be home – this very summer – but he won’t be; he can’t be! I want to see him, but I want him to stay in America, too! Can’t you understand what it’s like? Mam was my age when you and she said goodbye in your war, then she went to France to be near you! Try to understand how it is for me and Keth.’

‘I do, lass. I do. And happen it’ll be like you said. By the time you get into the Navy, we’ll all know where we stand, one way or the other.’ He took a handkerchief from his pocket, offering it, his expression tender with the love he felt for her. ‘So dry your eyes, our Daisy. Mam and me didn’t want there to be another war, and now there’s nothing we can do about it except to keep our chins up and carry on as best we can. Now how about a smile?’

‘I’m sorry,’ Daisy sniffed. ‘I really am. And I love you both very much and I don’t know why I filled that form in for the Wrens – I honestly don’t!’

‘Oh yes you do, Daisy Dwerryhouse!’ The tension had left Alice now. ‘You did exactly as I did. You listened to your heart instead of to your head. There must be a daft streak somewhere in us Dwerryhouse women. Now for goodness’ sake, let’s have that drink of tea.’ She flinched as a bomber flew over the house, the noise of its engines drowning out speech. ‘My, but that one was low!’

‘Aye. Loaded, they’ll be. It must take a bit of doing, getting one of those things off the ground,’ Tom frowned. ‘Going bombing again I shouldn’t wonder.’

‘Again. And they’re bits of lads, some of them. There was an air-gunner in the canteen a couple of nights ago; told me he was eighteen. Eighteen! Now I ask you, what age is that?’

‘Two years younger than me, Mam,’ Daisy whispered.

‘So it is, love.’ She raised her eyes to the ceiling. ‘And there’s another of them off over, an’ all. Well – God go with them,’ she whispered, her eyes all at once too bright, ‘and bring them all safely back.’

She turned her back so Tom and Daisy should not see her tears. Drew gone and now Daisy worrying to go and oh, damn the war! Damn and blast it!

Julia Sutton was crossing the hall as her husband, Nathan, came through the front door.

‘You’re late.’ She lifted her face for his kiss. ‘How were things at Flixby?’

‘The old man was sleeping when I left. He’ll slip away gently. Ewart Pryce gave him an injection so he isn’t in pain.’

‘Ah, well – there’ll be two more. Hear of one, hear of three, isn’t that what they say? Want a drink?’

‘Please. Have we any Scotch?’

‘Enough. But can anyone tell me why things we took for granted seem just to have disappeared? The distilleries haven’t suddenly been taken over, have they? The cigarette factories haven’t closed down?’

Only that morning she had stood twenty minutes in a queue for five – five, would you believe? – cigarettes. She had been so desperate for one she’d had difficulty not lighting up in the street there and then!

‘Shortage of materials, shortage of labour. Tobacco has to be brought here by sea, just like most of our food. The farmers are going to have to produce more, though they can’t grow sugar nor tea …’

Nor petrol, Julia thought. All her June petrol coupons used, and more than a week to go before she could get any more. Only a thimbleful left in the tank.

‘I’ll have to start riding my bike,’ she said, out of the blue. ‘Do me good, I suppose …’

‘It would. And you could tell yourself you were helping the war effort, saving petrol.’

‘I wouldn’t be saving anything, just eking out my ration. Thank goodness I drive a baby Austin. Your pa’s Rolls would guzzle up a month’s ration in two days!’

‘Pa put the Rolls in mothballs ages ago, and you know it. His eyes are getting worse, though he won’t admit it. He’s going to have to give up driving before so very much longer.’

‘But he’d be virtually marooned at Pendenys without a car,’ Julia protested. ‘He’ll just have to get a pony and trap. Mother had one in the last war; got quite good at it.’

‘And you, I seem to remember, were always to be seen biking furiously along the lanes,’ he smiled fondly.

‘Mm. Me and Alice both. We used to ride in the dark in winter – we had to. It was the only way to get to Denniston when we were –’

She stopped abruptly, her cheeks pinking. When she and Alice had been probationer nurses, she’d been going to say; when she’d been married to Andrew, that was, and desperate to get to France to be near him.

‘A long time ago, darling.’ Nathan accepted the glass she offered. ‘Woman – you’ve drowned my whisky!’

‘Sorry – only way to make it go further.’ She settled herself on the floor at his feet, leaning her back against his chair. ‘How old is the man who’s dying?’

‘Seventy-six next …’

‘It’ll be a long pull, then, when he goes.’ Seventy-five slow, sombre peals on the death bell; one for each year of his life.

‘No. No more passing bells. There was a letter from the Diocese office this morning. Bell ropes are to be tied up as a precaution. And we’ll have to stop the church clock striking, too. No more bells nor chimes – only for the invasion, if it comes.’

‘You mean not for anything?’ Church bells and the chiming of the church clock were a part of their lives.

‘Only if the invasion comes. The military will tell us when to ring them. As a warning, you see – to let people know …’

‘Then let’s hope we never hear them till it’s all over and we’ve won!’ What a chiming of bells there’d be then! When we won. There were some old miseries, Julia frowned, who said it would go on far longer than the last one did, especially as there seemed to be no stopping Hitler. ‘Will it last four years, Nathan? Is Drew going to be away all that time?’ The best years of his life, away from Rowangarth?

‘Barring miracles, Julia, I think he might. There’s even talk of women being directed into war work soon – compulsory, so they say. They might even send young women, if they aren’t married, into the armed forces.’

‘Send them, Nathan? But they can’t! Oh, my Lord! Tom Dwerryhouse’ll go berserk if they call Daisy up!’

‘But, sweetheart, there’s a lot of young women in the Forces already.’

‘Yes – but they are volunteers, there because they want to be or because they feel they should be. But the powers that be can’t take young girls from their parents and put them into uniform, dammit! And some of them are so innocent they don’t know how babies get there – or get out!’

‘They can, Julia. They can do anything they want if they think it’s justified. It’s done under the new law – the Defence of the Realm Act. They’re using it, now that Italy has declared war on us, to round up people here they think might have Italian connections or sympathies. They’ll intern them, just as they did to Germans living here when war broke out.’

‘And serve them right, too,’ Julia snorted. ‘Italy declaring war on us when we were on our knees, almost, after Dunkirk! Kicking us when we were down, that’s what! Mussolini is a pig! And I think I’ll have a whisky, too, and a cigarette. I need them!’

‘Yes. I think you’d better,’ Nathan said; said it softly and strangely so that Julia turned sharply.

‘Why?’ she demanded. ‘Have you some more miserable news for me?’

‘Depends on how you look at it, I suppose. It’s why I was so late tonight. I called in on Pa. It’s been on the cards for some time; this morning it was definite. They want Pendenys Place …’

‘Taking it, you mean? Commandeering it – lock, stock and barrel?’

‘Under the Defence of the Realm Act, they told Pa. But only Pendenys. The stock and the barrels Pa has a month to shift out. They’re letting him have the tower wing – what’s left of it, that is – to store all the stuff in. He’s getting a removal firm from Creesby to do it for him, then he’s got to hand the place over. They’re taking the stable block and the garages, too – even the kitchen garden.’

‘But what do they want Pendenys for – a hospital?’ Julia downed her drink almost at a gulp, so agitated was she. ‘What on earth can they do with it?’

‘I don’t know anything except that They want it, so there’s nothing anyone can do about it. Pa isn’t all that much bothered – or won’t be once the place has been emptied and everything locked up safely. He’s going to Anna, to look after her and Tatiana at Denniston, he says.’

‘But Anna’s got Karl to look after her! Your pa should come here to Rowangarth.’

‘Where you and Aunt Helen have me to look after you. And Denniston House isn’t far away – you above all should know that.’

‘Mm. About ten minutes by bike,’ Julia agreed.

Nathan drained his glass, setting it on the table at his side. ‘Pa seems to think Pendenys might be used for the Air Force – maybe for offices or accommodation for Holdenby Moor. It isn’t far from the aerodrome, when you think about it. But I’m not so sure. All the visits were made by army people and they seemed more concerned with its seclusion and how easily it could be made secure.’

‘For something hush-hush, you mean?’

‘Maybe for a bolt hole for high-ups in the Government or the Civil Service if the invasion happens.’

‘Or maybe for exiled foreign royals – perhaps even for our own, if they start bombing London.’

‘Lord knows,’ Nathan shrugged.

‘And He’ll not tell us,’ Julia pointed out irreverently and not at all like the wife of the vicar of All Souls’. ‘Hell, but I hate this war! They’ve taken Drew and we’re waiting here for Hitler to make up his mind when he’s coming! What are we to do, darling – and don’t say, “Pray, then leave it in God’s hands.” The Germans will be praying, too, and it looks as if it’s them God is listening to at the moment! No platitudes, Nathan Sutton, or I’ll thump you!’

‘All right – then how if we both have another Scotch? Just a small one …’

Julia gazed at her empty glass, then turned to smile at her husband.

‘You know something, Vicar – that’s a very good idea. And what the heck? We can only drink it once!’

She held out her hand for his glass, then walked to the table on which the near-empty decanter stood, frowning as she tilted it.

The Army – or whoever – was welcome to Pendenys, great ugly, ostentatious place that it was. Only Aunt Clemmy and her precious Elliot had liked it and they were both dead and buried.

Then she permitted herself a small, mischievous smile just to think of Aunt Clemmy’s ghost, weeping and wailing at the front entrance, cursing the dreadful, common people who had dared to take her beloved Pendenys Place.

But what on earth did they want it for?

3

Each evening when she got home from work, Daisy expected the letter to have arrived. It would be small, she supposed, the envelope manila-coloured with ‘On His Majesty’s Service’ printed across the top. And inside would be a tersely-worded message, telling her where and when to attend for her medical examination.

It was so long coming, though, that she began to think her application had been lost or ignored – or that the Women’s Royal Naval Service had such a long list of twenty-year-old shorthand typists that they weren’t all that much bothered about Daisy Dwerryhouse.

She began not to care, even to be glad, and only to scan the mantelpiece for Keth’s pale blue air-mail envelopes as she opened the kitchen door.

Since war started, Keth’s letters rarely came singly. Almost a week without one, then three or more would arrive, giving her news of the Kentucky Suttons and messages from Bas and Kitty, but mostly telling her he missed her and loved and wanted her. There were no more Washington postmarks and she ceased to wonder why he had been there.

She read his letters over and over, arranging them in date order. There were a great many; more than three hundred, packed tightly into shoe boxes in the bottom of her wardrobe and easily to hand because if things got worse and Holdenby was bombed, they were the first things she would grab and take down to the cellar with her.