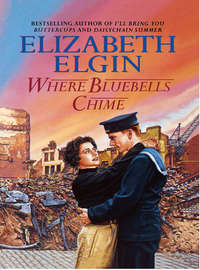

Where Bluebells Chime

Her cousin was right, of course. Apart from the blackout, there was little sign of the war in the tiny village between Oban and Connel. Just sight of the ferry from Achnacroish to Oban and the odd merchant ship making for the Sound of Mull. Certainly there were no aircraft armed with bombs and bullets, their wings heavy with fuel, struggling to take off. The bombers from RAF Holdenby Moor worried Agnes Clitherow. She flinched when they roared overhead, awoke with a start when, in the early hours of the morning, they returned from raids over Germany.

‘We are safer here on the west coast. If the invasion comes it will be from the south or the east,’ Margaret had urged and she was right without a doubt. Hitler’s divisions occupied France, Belgium and the Netherlands, had ports and aerodromes there in plenty. ‘Mark my words, Agnes, Hitler will not do the obvious. They are waiting for him to invade the south coast of England but in my opinion he’ll land in Yorkshire or Northumberland. He’s a sly one!’

‘Not for so very much longer?’ Helen’s words cut into the housekeeper’s troubled thoughts. ‘You aren’t ill, Miss Clitherow?’

‘No, milady, but I am getting older, and my cousin has offered me my own room. It’s so peaceful there in Scotland, and safe somehow.’

‘And you don’t feel safe here at Rowangarth?’ Helen Sutton knew how much her housekeeper disliked having the aerodrome so near. ‘You really want to go, Miss Clitherow? Are you and I to part after so long?’

‘Needs must, Lady Helen. You know how old I am and I’m mindful of the fact that there would always have been shelter for me here. But I’m of a mind to end my days with Margaret in Scotland. It’s why I’m giving notice now, and hoping it will be convenient for me to go in four weeks’ time.’

‘Miss Clitherow, you may leave as soon as you wish, but it will grieve me to see you go. I shall miss you greatly. Rowangarth will miss you.’

‘Oh, milady …’ Tears trembled on Agnes Clitherow’s voice.

‘Now don’t upset yourself,’ Helen soothed. ‘Scotland isn’t the other end of the world. We’ll all keep in touch. But promise me one thing? You know I wish you well in your retirement, but just if things don’t work out, I want you to know that you have only to ring me. There is room and to spare for you always here at Rowangarth. You’d never be too proud to admit that you missed us more than you thought, now would you?’

‘No. I wouldn’t,’ she sniffed. ‘This house has been like a home to me and where else would I turn, if trouble came? And like you say, Rowangarth is only a telephone call away. But if you’ll pardon me, milady – things to be done, you see …’ And if she didn’t get out of this dear little room she would break down and weep – a thing she had never done before – well, not in front of her ladyship, that was. ‘Perhaps if we could talk later? It has been distressing for me, telling you.’

‘And for me, too, learning I am to lose a splendid housekeeper and a dear friend. But if your mind is truly made up, then I promise not to try to persuade you to stay.’

‘Thank you. Thank you for everything, milady,’ the housekeeper choked as, for the first time in all her years with Lady Helen, she made a hasty, undignified exit.

Helen watched her go, heard the quiet closing of the door and the slow, sad steps along the passage outside, walking away from her.

But everything and everyone she had known and loved seemed to be leaving her now, she thought sadly. Soon there would be no one left. No one at all.

Jack Catchpole, son of the late Percy, and head – and since war started the only – gardener at Rowangarth, was not at all sure about the land girl Miss Julia had said would be coming. To help in the kitchen garden, she said, since they must grow all the food they could. Vegetables and fruits in season would help the war effort and Rowangarth, therefore, was entitled to apply for help from the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries – the Ag and Fish, most people called it.

What had surprised Catchpole, however, was that as in most things, Miss Julia had had her way in no time at all and now he must prepare himself for a female invasion of his domain.

He sucked on his empty pipe, contemplating the horrors of it. For one thing, she wouldn’t know a weed from a seedling and for another, she wouldn’t want to get her hands dirty nor break her fingernails which without a doubt would be long and painted bright red. And she would be late every morning, an’ all, and make up all kinds of female excuses when she wanted time off to meet her young man or have her hair permanently waved. In short, she was not welcome.

It came as a great surprise, therefore, and something of a shock to see a young woman, smartly dressed in Land Army uniform, advancing upon him just as the kettle on the potting shed hob was coming to the boil and he had emptied his twist of tea leaves and sugar into the little brown teapot he had used for years and years. He watched her, saying not a word until she stood before him, eyes wide.

‘Are you the head gardener?’ she asked.

‘Aye.’ His eyes did not waver.

‘I think you’re expecting me, sir. I’m your land girl and I’m willing to learn …’ She let go her breath in a little nervous huff.

‘Aye.’ Catchpole stuffed his pipe into the pocket of his shirt. ‘Well, the first thing you learn in my garden is not to call me sir. My name is Jack Catchpole – Mister Catchpole to you. And what might your name be?’

‘Grace Mary Fielding, Mr Catchpole, but people call me Gracie. Gracie Fielding – Gracie Fields, see? Well, when you come from Rochdale, what else?’

‘What else indeed?’ Catchpole liked Gracie Fields and her happy, brash voice. Made him laugh, Our Gracie did. ‘So, young Gracie Fielding, what made you choose market gardening in general and Rowangarth in particular?’

‘Oh, I didn’t, Mr Catchpole – choose either, I mean. I just got sick of streets and mills and joined the Land Army so I could be in the country – and do my bit, of course. And it was the Land Army chose to send me here.’

‘Mills, eh? Cotton mills?’

‘Mm. All the women in our family worked in the mills, but Mam said she wanted better for me. “Gracie isn’t going in t’mill,” she said and she worked extra hours to send me to the Grammar School.’

‘So you got yourself a better job – kept away from the looms, then?’

‘A better job – yes,’ she grinned, ‘but at the mill, as a wages clerk. Would make Dickie Hatburn’s cat laugh, wouldn’t it?’

‘And who might Dickie Hatburn be?’

‘Dunno, but he must have had a cat, that’s for sure.’ She threw back her head and laughed and her teeth were white and even. Her eyes laughed, too.

‘Do you like cats, Gracie Fielding?’

‘Not as much as dogs.’

‘Then that’s the second thing you learn in my garden. Cats is not welcome. When you see one you chase it, don’t forget. Cats wait till you’ve made a nice soft tilth and sown your seeds careful, like, in nice straight rows, then they’ve the cheek to think you’ve done it specially for them. Soon as your back is turned, they’re scratching about among your little seeds and you know what they leave behind them?’

‘Oh I do, Mr Catchpole, and I’ll chase them.’

‘And dogs, too. Dogs’re not welcome in my garden either, unless accompanied by a responsible adult and secure on the end of a lead.’

‘I’m learning,’ Gracie smiled.

‘Then rule number three. At a quarter past ten exactly, I mash a pot of tea. Most days there’s a fire in the big potting shed if we can find wood, and it’s going to be one of your jobs to see that I get my tea on time.’

‘Ten fifteen exactly.’

Catchpole took out his pocket watch, then glanced in the direction of the potting shed.

‘Water’ll just about be on the boil. Tea’s in the pot. Reckon it might run to two. You’ll find an extra mug on the top shelf beside the bottle marked poison.’

Gracie entered the dark shed. It smelled of earth and bone meal and smoke from the crackling wood fire in the little iron grate. On the hob a kettle was just beginning to puff steam.

She searched the top shelf to find a blue enamelled mug, rinsed it in the rainwater butt outside the door, then shook it dry. She liked Mr Catchpole and the smell of his big shed; liked his garden with its high, red-brick walls with fruit trees growing up them and she liked the straight, weed-free paths and their little clipped hedges.

‘I’m glad I’m here,’ she smiled, handing him the bigger mug, settling herself beside him. ‘It’ll be better than working on a farm, shovelling manure.’

‘And what makes you think you won’t be shovelling manoor here?’ He jabbed the stem of his pipe in the general direction of a large, steaming heap in a distant corner of the garden. ‘That manoor came here this March and there it’ll stay till it’s good and black and rotted down and smells as sweet as a nut. And then, I shouldn’t be at all surprised, you’ll shovel it into a barrow and you’ll spread it down the potato rows and anywhere else I think fit for it to go. It’ll be the land girl’s job.’

‘Rule number four,’ she said gravely. ‘Manure.’

‘That’s it. And then, when we’ve used up that heap – next spring, that’ll be – us plants marrows there. Alus. Marrows is greedy feeders and they like growing where a manoor heap has wintered. Ground full of goodness, see. There’s a great call, these days, for marrows for stuffing.’

‘Stuffing,’ Gracie echoed, never having eaten a stuffed marrow and making a mental note never to eat one in future.

Catchpole supped appreciatively. The lass could mash tea and she had a happy face and could take a bit of teasing.

He glanced at her outfit, taking in the khaki knee-stockings, the shirt and green tie; the short, smart jacket and the hat, tipped to the back of her bright yellow curls.

‘Hope you don’t intend coming to work all dressed up like that,’ he remarked, eager to find just one fault.

‘Bless you, luv, no! I’m wearing my walking-out togs just to make an impression. Tomorrow, I’ll be wearing my dungarees and a cool shirt – and my good thick boots!’

Catchpole nodded, mollified, drained his mug then placed it on the ground at his feet.

‘You got a young man, then?’

‘One or two, Mr Catchpole, but none of them serious. Well, it’s best not when there’s a war on. Don’t think I’d like having someone I cared about very much away at the war.’

‘Ar.’ The lass had sense. ‘Still, can’t sit here all morning nattering. Work to be done. Us’ve got to dig for victory, or so the Government tells us.’

Gaudy posters everywhere urged it. ‘Dig for Victory!’ they exhorted. Britain needed food, so lawns must be dug up and cabbages and potatoes planted instead. Those without gardens were offered allotments; flowerbeds in parks were planted with peas and beans and lettuces. Any grassy stretch came under the plough and this year, where children once played and dogs had been walked, wheat and oats and barley were already turning from green to gold, soon to be harvested.

Dig for victory! Every spadeful of earth turned over, every potato picked, was a second in time off the duration of the war, and Britain dug furiously.

‘Then can’t I stay, Mr Catchpole – start work right away?’

‘You could, if you wasn’t all togged up like that.’

‘Then why don’t I go back to the hostel and change into my dungarees? And I can pick up my sandwiches whilst I’m about it. And Mr Catchpole – why is our hostel called a bothy?’

Questions, questions! ‘A bothy,’ he sighed, ‘is a place where apprentice lads lived. Young gardeners, stable lads and the like. Every big house has a bothy, only once, in the old days, they were filled. Mrs Purvis looked after them all.’

‘Mrs Purvis who’s our cook?’

‘That same lady. When the garden apprentices were taken into the militia, she had nothing to do. Lucky for her you land girls came along.’

‘She’s nice. She’s been asking us, now the apples are ripening, to try to get her some windfalls, then she’ll make us an apple pie for Sunday dinner. She’s a good cook.’

‘Well, you’m welcome to any windfalls you can gather here. There’s a few about, over by the far wall. Now off with you, lass! I’ll be over yonder when you get back, hoeing the sprouts. You know what sprouts are?’

‘Course I do – but I’ve never seen them growing.’

‘Well, from now on and for the duration, Gracie Fielding, you’m going to learn how to grow ’em – aye, and peas and beans and potatoes and more besides.’

‘Suits me, Mr Catchpole.’

He watched her go. Happen he just might make something of the lass from Rochdale. She had a nice smile and a ready laugh and he’d especially looked at her fingernails, which were short cut and unpainted.

‘Us’ll see how you shape up, Gracie Fielding,’ he murmured to her retreating back and surprised himself by noticing she had a nice, neat little bottom.

He chuckled mischievously, wondering how long it would be before the lads at the aerodrome were wolf-whistling his land girl.

Picking up the mugs, he rinsed them in the water butt and returned them to the shelf beside the bottle marked poison. Then he took the teapot and emptied the leaves on the compost heap, making a mental note to instruct Gracie about compost heaps and their value in the order of things.

He reckoned the lass would be a quick learner and was very surprised to find himself looking forward to her return.

‘I see they’re making the Duke of Windsor governor of the Bahamas,’ Helen Sutton murmured over the top of the morning paper.

‘Best place for him,’ Julia grunted without looking up from her plate. ‘Hope he takes her with him. Shouldn’t wonder if Mr Churchill isn’t behind the move. The man’ll be out of harm’s way there. Tell me something important.’

‘We-e-ll, it says here that there have been air raids on Swansea and Falmouth, and convoys in the Channel have been attacked. And more raids on Clydeside and the south.’

‘Looks as if we are being softened up for the invasion,’ Julia shrugged.

‘Don’t say that, please.’ Helen Sutton laid down her newspaper. ‘Drew is in the south, don’t forget.’

‘Drew is just fine. I’d know inside me if he wasn’t.’ Julia picked up the paper, shaking it open. Newspapers were easily read these days. Sometimes containing no more than eight pages, they were quickly scanned. ‘Well! Here’s something you missed. That dratted Lord Haw-Haw! Last night, it says, he broadcast a final appeal to reason to the British, urging them to make peace with Germany. The cheek of the ruddy man!’

‘I saw it, Julia. I didn’t think it worth comment. And you know I have forbidden anyone in this house to tune in to him.’

‘But people do, you know. They reckon he’s a good laugh.’

‘Oh, no! Some of the things he says are remarkably true, or so they say. He doesn’t amuse me!’

An Englishman – no one could be quite certain of his identity – broadcast regularly from Germany. He had an arrogant, nasal voice that some likened to the braying of an ass. So Lord Haw-Haw he had become, and almost as much a part of listening in to the wireless as Tommy Handley or Henry Hall, and though no one at all admitted to having heard him, he was, nevertheless, regularly reported in the newspapers. Completely as a joke, of course!

‘Well, we don’t want peace with Hitler – not on his terms, anyway. Oh, wouldn’t he just love rubbing our noses in it? We’ll manage, Mother. He knows what he can do with his offer of peace as far as I’m concerned. And here’s another bit you missed. The Government says that no more cars are to be manufactured – not for civilians, that is.’

‘Civilians must make sacrifices,’ Helen sniffed. She disliked cars, refusing to learn to drive. You couldn’t blame her, Julia thought, when Pa had killed himself in a motor on the Brighton road, trying to reach sixty miles an hour.

‘Oh, and something else,’ she smiled, folding the paper. ‘Alice told me last night. The LDV boys have been given uniforms at last and they’re to be called the Home Guard. They’re to have shoulder flashes to sew on, and tin hats, too, just as if they were soldiers. They’ve made Tom a corporal. I think he’s quite chuffed about it. All he wants now is for them to be issued with rifles, then they’ll be ready for the Jerries. If they come, of course.’

‘And do you think they will, Julia? Honestly?’

‘Every night I pray they won’t but truly, Mother, where else is Hitler to go now? America is too far away; Russia is an unknown quantity and anyway, even Hitler wouldn’t be fool enough to take on such a big country. They’ve already taken the Channel Islands – it’s likely we’ll be next. Yet Nathan says he feels that we won’t be invaded. Apart from his faith in God, he says he just knows inside him we’ll be all right. So let’s not worry too much, uh? Every day is a bonus, so chin up, dearest. We’ll manage.’

‘Well, Nathan did tell me that according to the so-called experts, Hitler will hold back until some time about mid-September. Conditions would be better then, and the tides just right.’

‘Well, there you are! We’ll be good and ready for him come September. Let’s not think about it any more for a while.’

She looked up as the door opened and a smiling Mary brought in the morning post.

‘The Reverend is back from early church, Miss Julia, and there’s a letter from Sir Andrew.’

Eagerly Helen reached for it, tearing it open. It occupied just half a sheet and was soon read.

She passed it to her daughter then smiling happily she said, ‘He’s just confirming what he told us on the phone, Mary. Drew’s leave is definitely on. He says his divvy has okayed his application. What is a divvy, Julia?’

‘His divisional officer, I think, but who cares as long as he’s coming!’

Drew home! Her son – Alice’s son – coming on leave. So go to hell, Hitler! We don’t want your peace, at any price!

5

Gracie gazed around her, cheese sandwich poised. Only her second day at Rowangarth, yet it seemed as though she had always worked here; as if that other life of streets and mill hooters and wage packets had never been – except for Mam and Dad, that was, and Grandad.

The air seemed to shimmer golden, dancing with butterflies. She had never before seen so many; not all at one time. To her right, rooks cawed and flapped over the distant trees. Busy getting their second broods out of the nest, Mr Catchpole told her; told her, too, how special that rookery was to Lady Sutton and how, if ever those big, black birds left to nest in some other place, sorrow and tragedy would come to the Garth Suttons, or so legend had it.

‘Who are the Garth Suttons?’ Idly, she flicked breadcrumbs from her overalls.

‘Why, you’m working for them. There’s two Sutton families hereabouts, see. Those as lives here at Rowangarth – them’s the Garth Suttons – and there’s the Suttons at Pendenys Place as folks call the Place Suttons. And there’s Mrs Anna Sutton of Denniston House. Her’s a widow and an offshoot of the Place Suttons. Now, the Garth Suttons have the breeding and the title; the Place Suttons,’ he added, right eyebrow raised, ‘have the brass. Mr Nathan, as is married to Miss Julia, was a Place Sutton but he’s a decent gentleman, like his father …’

Gracie nodded, anxious not to interrupt, because people who lived in big houses – though she had come into contact with very few – intrigued her. Sometimes, on a day trip on the chara, she had passed such houses, all dignified and aloof, and wondered who lived in them and how many servants they had or if they ate off gold plates. And then her Lancashire practicality had taken over and she had tried to work out why they needed so many rooms and whoever found time to clean all the windows.

‘Tell me some more, Mr Catchpole …’

‘Not a lot to tell. I served out my apprenticeship at Pendenys. Wouldn’t have done for me to do it here, not with my dad being head gardener. But I was glad to finish my time and to come to Rowangarth as under-gardener. A right martinet that Mrs Clementina Sutton at Pendenys Place was. Had her servants bobbing and curtsying all the time. Not like our Lady Helen, who don’t hold with it.

‘Mrs Clementina’s father was a self-made millionaire and her his only child, so she copped for the lot.’ His eyes took on a remembering look. ‘By heck, lass, there’s things I could tell you about that one. Married Mr Edward Sutton, who was born here at Rowangarth. A case of brass marrying breeding, but it didn’t ever make a lady of her. An ironmaster’s daughter, that’s what, and she never changed. Silk purses from sows’ ears, tha knows …’

He bit savagely into a sandwich. At midday, Jack Catchpole was in the habit of eating a good, sustaining meal with his feet under his kitchen table, but today he had been fobbed off with sandwiches, and all on account of those Spitfires. Derisively he investigated the contents of the sandwich.

‘A man’s expected to dig for victory on fish paste?’ he snorted.

‘Mrs Catchpole not very well, then?’

‘Nay. Nowt like that. She’s busy collecting aluminium; her and Alice Dwerryhouse and Miss Julia got it all organized.’

‘The Government, you mean – wanting people’s pans to melt down for planes?’

‘That’s it. Got a right pile already in one of the stables at Rowangarth. Folks is chucking out pans like there’s no tomorrow. But I suppose we need fighters. Us lost a lot at Dunkirk, tha knows.’

Gracie knew. She had wept with pride when the soldiers were snatched off the beaches. It had been around that time, in a heady haze of patriotism, she had joined the Land Army.

‘Any road,’ Catchpole was eager to return to the ins and outs of the Suttons, ‘young Sir Andrew comes on leave soon, we hope, from the Navy. He’ll be down here for sure, having a look at the gardens. He’s real fond of the orchid house – but I’ll tell you later about her ladyship’s special orchids, the white ones. Very sentimental about the white ones, she is.’

‘So when he comes here, what do I call him?’ Gracie had never met a gentleman of title before.

‘Why, you gives him his rank as is due to him. “Good morning, Sir Andrew,” you’ll say, then like as not he’ll ask you to call him Drew as folk who’ve known him since he was a babbie alus do. Mind, when he came of age, some started to call him Sir Andrew – but more as a politeness. The lad hasn’t changed, though. He’s a credit to her as had him, and her as reared him. But we haven’t all day to sit here nattering.’ He threw the remainder of his sandwiches to hopefully waiting sparrows. ‘There’s a war on and we’ve got to get them potatoes and marrows ready for when the market man calls – and a score cabbages he wants, an’ all.’

‘But you’ll tell me some more, tomorrow – about the Suttons?’ Gracie begged. ‘About the one who had him and the one who brought him up, I mean.’ That small snippet had intrigued her. ‘Did Sir Andrew have a nanny?’

‘No, he didn’t. But that’s another story. For tomorrow,’ Catchpole chuckled. He could get to like this lass. Happen, if he and Lily had had bairns of their own, one of them might have been like young Gracie. ‘So on your feet, lass. Let’s get digging up them potatoes – for victory!’

Though when that victory would come, he thought mournfully, only the good Lord knew – and He wasn’t telling!

The first sight of Rowangarth had always been special to Drew Sutton. To walk the long slow curve of a drive lined with beeches and oaks and all at once to come upon the old house always aroused an ache of tenderness in him. But this afternoon it was particularly special and achy because he hadn’t seen it for six months and only now he realized how much he had missed it.

Mullioned windows still shone a welcome; the roof still sagged and the rose-red bricks were still smothered in blowsy Bourbon roses and clematis.

God – don’t let me die and lose it. The heart-thumping ache turned to panic inside him. Let me live through this war.

‘Stupid clot!’ he hissed. It wasn’t down to God. It was like the old Chiefie in signal school said: you just had to accept that there was a time to be born and a time to die. And you died when – if – your number came up. So best not worry overmuch about it, Chiefie said comfortably, because worrying only wasted the time you had left.