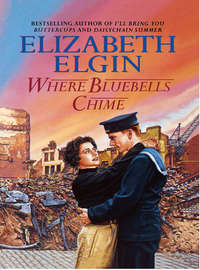

Where Bluebells Chime

Tonight, there had been a letter from Drew.

… all at once it began to make sense, fall into place. I realized, the other afternoon, that I could sort the dits and the das into letters and figures – actually read them.

Daisy frowned. Dots and dashes, did he mean?

Even so, I found it hard to believe when they told me I had passed out. I am now a telegraphist and will be going back to barracks soon for drafting.

Don’t write back, Daiz, because there is a strong buzz we will be given leave. I’ll try to give you a ring if it is likely to happen, though there is always a queue at the phone box and delays getting through. Don’t be surprised if I just arrive without warning …

Drew coming on leave – but when? She felt so lonely and alone that tomorrow wouldn’t be soon enough. There seemed nothing, now, to life but working, wondering, worrying – and wanting. Wanting Keth, that was; wanting him here to touch and kiss and make love to her; wanting him to stay in Kentucky so They, the faceless ones, should not take him into the Army.

She ought to be ashamed, really. Compared to some, her life hadn’t changed overmuch. This far, Keth was out of harm’s way, Keeper’s Cottage had not been bombed, the evening air was heavy with the scent of newly cut hay and Rowangarth was still there, its sagging old roof just visible over the treetops to remind her that some things endured.

It was sad, for all that, that France had finally given in, been forced to sign a surrender in the same railway carriage in which Germany signed the Armistice at the end of the last war – Dada’s war. How humiliating for the French; how Hitler must have gloated.

And now, fresh fears. German soldiers had occupied Guernsey and Jersey, and those islands almost a part of Britain. It sent fear screaming through her just to think about it.

Only one thing was certain, Daisy admitted as sudden, silly tears filled her eyes. England – Great Britain – stood alone now, backs to the wall. This cockeyed little island was going to have to take whatever the Nazis threw at it, or give in. And since Mr Churchill had said we would never surrender, it seemed we were in for a bad time. A shiver of pure melancholy ran through her. How brave would she be when – if – it happened?

Keth, I need you so …

Mary Strong gave a final loving rub to the silver punchbowl she was polishing, then wrapped it in black tissue paper, wondering if Will was right and her ladyship really was going to hide away the silver and valuables – just in case.

If she were given a pound note for every time she had cleaned that bowl over the years, Mary sighed, she could buy the most beautiful bridal gown in York and still have a tidy pile left over.

Mind, she would still work as parlourmaid for Lady Helen when she and Will were wed. Once, it was demeaning for a married woman to work, unless she were a widow and had little choice. But war had come again and married women without encumbrances were expected to work.

Yet what concerned Rowangarth’s parlourmaid more immediately was what to wear to her wedding four weeks hence. She was the first to admit she was past bridal white and anyway, a once-only dress was an extravagance she didn’t subscribe to.

Now if Alice could be persuaded to make her something pretty yet sensible, she pondered, and she could find a nice matching hat, her problem would be solved.

‘I’ll ask Alice,’ she said to Tilda, ‘to make my dress – for the wedding, I mean …’

‘I’d concentrate, if I were you,’ Tilda frowned, ‘on getting Miss Clitherow’s sitting room seen to. She’s back tomorrow and you could write your name on the top of that table of hers. I’ve no time, Mary, what with the bottling to see to and the raspberry jam to make!’

‘Oh? And where did Tilda Tewk get sugar for jam, then?’

‘Never you mind!’ It wasn’t only silver could be hidden away! There were twenty two-pound bags of sugar, an’ all, and Hitler, if he came, could draw her teeth one by one before she’d tell them where so much as a grain was hidden. ‘And don’t forget, herself’ll be on the night train and back here before noon!’

‘Aye.’ Mary wasn’t likely to forget. It had been grand with the housekeeper away and just her and Tilda to see to things. ‘She’s been gone so long I thought we’d seen the back of her, but I’ll give her room a going-over in the morning.

‘Now would you favour blue for a wedding dress, Tilda, and a matching hat? And do you think Mr Catchpole would make me up a few flowers? Not a bouquet – not without a veil – maybe a little posy, though.’ Miss Julia had worn blue and carried white orchids – at her first wedding, that was, to the doctor, Andrew MacMalcolm.

She lapsed again into daydreams and Tilda, who was nothing if not practical, knew better than to interrupt them. But she’d be glad when Miss Clitherow got herself back; when Mary and Will were safely wed and when – and may God forgive her for such thoughts – Hitler had made up his mind about the invasion. Maybe then, things could get back to normal – or as normal as they ever could be with a war on.

Tilda sighed, remembering the last one, then turned her thoughts to the evening meal ahead. She supposed it would be rabbit. Again.

‘Do you think, dear,’ Helen Sutton asked of her daughter at breakfast, ‘that either Will or Catchpole could be persuaded to look after a few hens?’ Eggs were rationed now, and sometimes to only one each person a week. ‘Surely we could keep them on household scraps and gleanings of wheat and barley?’

‘We could ask. Polly Purvis has six Rhode Island Reds at the bothy. She says they are laying well – a couple of dozen eggs a week. She gives the land girls a boiled egg apiece every Sunday for breakfast and keeps what’s left for cooking. But perhaps we should ask Will? Catchpole has more than enough on his plate. He can just about manage the kitchen garden on his own, but he’s not going to have the time to grow flowers.’

Growing flowers was unpatriotic, the Government pronounced. ‘Dig for Victory!’ the posters demanded, with people being urged to plant cabbages, leeks and peas instead of flowers.

‘In the last war we ploughed up the lawns and grew potatoes,’ Helen murmured. Beautiful camomile lawns were turned under the plough, but they had been hungry then. Maybe before this one was over they would be hungry again. It was a distinct possibility when so many ships carrying food were being sunk every day by U-boats.

‘I’ll have a think about the hens, but first I think we should seriously consider getting some help for Catchpole.’

‘But how, Julia? They don’t consider gardening to be a reserved occupation.’ They had taken the garden apprentices into the militia and a waste of six years of training when you considered that two of them were in the infantry and one consigned to an army cookhouse.

‘No, but growing food is important and with a bit of help our kitchen garden could supply no end of vegetables and soft fruit. Anyway, I’m going to try.’

‘But where are we to find another gardener?’

‘You’ll see.’ It was such a mad idea, Julia supposed, she just might bring it off. ‘Tell you later,’ she smiled mysteriously. ‘And that was the postman, if I’m not mistaken. Bet you anything you like there’ll be a letter.’

From Drew, of course. No other letters mattered.

Daisy sat on the gate, waiting for Tatiana. It was where they usually met; halfway between Keeper’s Cottage and Denniston House, where Tatiana lived with her mother, Anna, with Karl, the big, black-bearded Cossack, to watch over them; was where, soon, Tatiana’s grandfather would be living when he handed over Pendenys Place to the Government.

Daisy hoped Rowangarth would escape. It would be awful having the military there, especially if they wanted Keeper’s Cottage, too.

But They could do anything they wanted now, and no one’s house – or car or boat, even – was safe if They decided they had greater need of it. For the war effort, of course. Mind, Mam thought it was a good thing about Pendenys and that Mr Edward would be better off living at Denniston. ‘All on his own in that great pile of slate and stone, like living in a cathedral.’

Daisy jumped off the gate as Tatiana arrived, red-faced from pedalling.

‘I am sick, sick, sick of old people,’ she announced dramatically, leaning her cycle against the hedge. ‘It was awful at Cheyne Walk!’

‘Well, you’re back home now,’ Daisy offered mildly because she was used to her friend’s fiery outbursts. Probably something to do with her being half-Russian.

‘Yes, thank God! Grandmother Petrovska was her usual awful self and Uncle Igor was rushing around making sure they weren’t going to be interned.’

‘But they won’t be. We aren’t at war with the Russians.’

‘Not yet, but we will be, Grandmother says. And don’t call them Russians, Daisy. They are Communists, not real Russians. They’ve made a pact with Hitler, you know.’

Daisy did know. Dada hadn’t been able to understand it. Communists and Fascists should be natural enemies, he’d said.

‘So what was so awful about staying with your grandma?’ Daisy demanded.

‘Oh, it was Grandmother, I suppose, being stubborn.’ Tatiana took a deep breath, sighing it out dramatically, leaning her elbows on the gate, gazing out over the field of ripening wheat. ‘Mother wants her to pack up and leave London – stay at Denniston for the duration. She thinks London will be heavily bombed soon. Stands to sense, doesn’t it? Hitler’s got to knock out London before he invades.’

‘We-e-ll, yes …’ It made sense, Daisy was bound to agree, running her tongue round lips gone suddenly dry.

‘And all the ports, too, Uncle Igor said.’

The ports, too, and Drew was near Plymouth.

‘So it was better, Mother said, for Grandmother to move out. Apart from the two aerodromes, there isn’t a lot around Holdenby for the Luftwaffe to waste its bombs on.’

‘So when is she coming?’ Daisy had met the autocratic Countess Petrovska and felt sorry for Tatty.

‘Oh, she isn’t. Refused point-blank. She said if she left Cheyne Walk, They would take it because there’d be no one living in it.

‘“I hef lorst my beautiful house in St Petersburg and my estate at Peterhof to the rabble. I vill not give up this one, too,”’ Tatiana mimicked. ‘And I suppose you can’t blame her. Drew said he’d hate it if the Communists had taken Rowangarth.’

‘But there aren’t any Communists here.’

‘No, but They might commandeer it, like Pendenys.’

‘For goodness’ sake, Tatty, don’t be so miserable!’

‘I can’t help it. It’s my Russian soul.’

‘Don’t be daft! You’re as English as I am.’

‘Half-English. I speak the mother tongue, don’t forget.’

‘Y-yes.’ Daisy was forced to admit it. Tatiana Sutton spoke the politely correct Russian learned from her mother but she was fluent, too, in the dialect spoken by Karl, a Georgian by birth. Tatiana, when provoked, had the advantage of being able to let fly a string of Russian swear words – learned from Karl – and get away with it. ‘But tell me – how was London?’

‘Poor old place – it seemed a bit bewildered. Barrage balloons in all the parks and sandbags everywhere. And it’s so completely dark now at nights. The shops haven’t a lot to sell. Mother didn’t buy a thing except a lipstick, and she had to stand in a queue for half an hour to get it. And there are uniforms everywhere. Such gorgeous men, and all of them going to war.’ She sighed loudly and with regret. Such a waste when she, Tatiana Sutton, hadn’t even been kissed yet – leastways, not with passion. ‘It makes you want to join up, doesn’t it?’

‘I suppose so. As a matter of fact,’ Daisy took a deep breath, ‘I have joined up.’

‘Wha-a-t? You mean you’ll be leaving, too? But, Daisy, you can’t! Drew’s gone, and Kitty and Bas can’t visit any more, and Keth’s stuck in America! If you go, there’ll be only me left out of the entire Clan!’

‘I know, and I’m sorry I did it. But don’t worry overmuch. They haven’t even acknowledged my application yet, and not a word about my medical. I could be months and months waiting.’

‘So what are you joining?’ Tatiana was piqued.

‘The Wrens, if they’ll have me. It’s got to be, you see, because of Drew. I hate working in that shop and I thought that if anything I could do would shorten the war by just one week, then I should do it. I want Keth home – but not till the war is over.’

‘Then that does it! If you can volunteer, so can I! I think I might go for the ATS. Well, the Suttons have always joined the Army, haven’t they?’

‘Until Drew – yes. But you can’t, Tatty! Have you thought about what your grandma would say?’

‘Oh, bugger Grandmother Petrovska!’ Tatiana could swear in English, too. ‘I’m sick of her and her everlasting black! Imagine – she’s still in mourning for Czar Nicholas and him dead more than twenty years!’

‘But it won’t be a bed of roses. Don’t expect it to be fun – in the Forces, I mean.’

‘Anything would be better than having Grandmother living at Denniston, because London will get bombed and she will have to leave.’

‘But your mother wouldn’t let you. You’re not twenty-one yet.’

‘Neither are you. Did your father give his permission? My mother will say I can, anyway.’

‘She won’t, and you know it. Dada didn’t sign for me to go. I sort of did it for him. He hit the roof!’

‘Then I shall sign Mother’s name. Aleksandrina Anastasia Petrovska Sutton. I know exactly how she does it.’

‘Oh, don’t let’s talk about the war! I’m afraid, really, about the invasion.’

‘So am I. They might treat us like they treated the Poles. And Grandmother wouldn’t help. She’d shout at them, if they came – all sorts of insults. We’d end up against the wall, being shot!’

‘Don’t say things like that, please. Let’s talk about Drew. Aunt Julia says he might be home on leave soon.’

‘He might?’ Tatiana brightened visibly. ‘There’d be half the Clan together again.’

‘Mm. And I could ask him for a few tips about the Wrens – what to say, I mean, if they ask me what I want to do.’

‘So they won’t put you in the cookhouse, you mean?’

‘Sort of. And in the Navy they call it the galley.’

‘Whatever,’ Tatiana shrugged. ‘But they do that, you know. If you can cook, then they’d put you in an office and if you can type –’

‘Which I can.’

‘Exactly. They’d probably put you on a barrage balloon, or something. They do it on purpose.’

‘It wouldn’t be that. I think the Air Force looks after all the barrage balloons. But I stood in a queue in Woolworth’s, yesterday, and guess what?’ She was anxious not to talk about the war any more. ‘I got a jar of cold cream.’

‘Lucky dog! Tell you what – let’s go back to Denniston and have a root through Mother’s make-up. She’s out do-gooding for the war effort. She won’t be back till late.’

‘Could we? What if she caught us?’

‘She won’t. Come on!’ An aircraft flew low overhead and Tatiana squinted up into the sky. ‘Ooh, just look at that! It’s a Whitley.’ Tatiana was good at recognizing aircraft. ‘They’ve got some at Holdenby Moor to replace the old Hampdens. And don’t you just love those aircrew boys? Aren’t they marvellous? I could fall head over heels for every one of them!’

‘No you couldn’t, Tatty. They’re very young – most of them not old enough to get married. And they get killed – all the time. But no more war talk – please.’

‘Oh, dear. Whatever next?’ Helen Sutton looked up from the evening paper she was reading as her daughter came into the room. ‘Our allies, Julia, yet we’ve sunk the best part of the French fleet. They were anchored somewhere in North Africa and our navy just turned their guns on them. Sank them, and more than a thousand killed. Well, I hope,’ she breathed, tight-lipped, ‘that Drew will never be called on to do anything so awful!’

‘You’re right. It is awful. But did we have any choice, Mother? We couldn’t let Hitler get his hands on those ships.’

‘But the French captains wouldn’t have let that happen. A lot of their ships have already sailed into British ports – and the French fought alongside us last time, remember.’

‘I know – but there’s another war on now and we can’t afford to use kid gloves, these days – not when we’re up against it, like now. But I think I might have some good news for you. You know I said I wanted to get help for Jack Catchpole? Well, I just might be lucky. I think we’re getting a land girl.’

‘But I thought land girls worked on farms.’

‘They work on the land, whether it’s farmland or Rowangarth kitchen garden. They’re there to help grow food and we could send no end of stuff to the Creesby shops. And a land girl could look after some hens for us. I went to the bothy – well, they call it a hostel, now – and I was lucky. Both the warden and the forewoman were in, and both of them thought Rowangarth could qualify. They were very nice and told me who to contact to get things going. We might have one before the month is out. Couldn’t be in better time, either, for the soft fruit.’

‘But how will Catchpole take it? He wouldn’t be getting an experienced gardener, would he? I believe some land girls come from towns and can’t milk a cow, even.’

‘But we haven’t got any cows. Anyway – can you milk a cow, Mother?’

‘No. But I could learn if I had to, I suppose …’

‘There’s your answer then. She’ll do just fine with Catchpole watching her. I’ve asked him, by the way, and he says as long as she doesn’t mind getting her hands dirty and is willing to learn and doesn’t give cheek, he said he would at least give it a try. So it’s fingers crossed. I think they’ll give us one. After all, we didn’t make a fuss when they asked us to let them have the bothy, and we supplied them with a cook, don’t forget.’

‘If we’d said no, they’d have taken it, for all that.’

‘But we didn’t say no. We co-operated and did all we could to help, so they owe us a land girl.’

‘I suppose so …’ Helen Sutton was not entirely convinced, but Julia would never change, would always rush in without too much thought.

‘By the way,’ Helen called after her daughter’s retreating back, ‘Nathan wants to see you about something. He’s in the library.’

And they could but try, she acknowledged as the door banged noisily shut. Yet for all that, she hoped that the young lady, if ever she arrived, didn’t come complete with bright red lipstick and painted nails to match. Catchpole wouldn’t like that at all.

The telephone rang shrilly and she heard Julia crossing the hall to answer it. She knew it was good news, even before the door flew open and a flushed and smiling Julia announced, ‘Drew’s coming on leave! Next Thursday, for ten days, he said!’ She gathered her mother into her arms, hugging her fiercely. ‘Isn’t it wonderful? Must just tell Nathan, then I’ll give Alice a ring!’

She was gone in a flurry of delight before Helen could even ask when her grandson would be arriving and if he wanted meeting at Holdenby station.

Then she smiled and picked up the framed photograph of a young sailor from the table beside her chair. His hair was cut much too short, but he smiled back at her exactly as Drew had always done.

Drew. Sir Andrew Sutton, really – Giles and Alice’s son. Coming home on Thursday; home to Rowangarth.

But Thursday was all of five days away – a hundred and twenty long, slow hours away. However was she to endure them?

4

Never in her life had Agnes Clitherow been so glad to see Rowangarth. A feeling of homecoming wrapped around her and almost made her regret what she and her cousin Margaret had decided, but she shook such thoughts from her head, picked up her cases and walked, straight-backed as ever, to the kitchen door. As Rowangarth’s housekeeper she had a right to enter by the front, but to do so would necessitate the ringing of the doorbell and that, at half-past six in the morning, was simply not done.

‘Miss Clitherow!’ Tilda gasped at the sight of the dishevelled lady who leaned against the door jamb. ‘Oh, come in, do!’ She guided her to a chair, all the while clucking and soothing as the occasion seemed clearly to demand, then set the kettle to boil on the gas stove. ‘A good strong cup is what you need. Been travelling all night, have you?’

‘Oh, Tilda!’ She had indeed made the overnight journey, which from Oban to Glasgow had passed without too much discomfort. But from Glasgow to York! ‘Never take the night train!’

Packed to overflowing it had been with soldiers with respirators and kitbags, airmen with kitbags and respirators and a great many sailors with the added encumbrance of rolled and lashed hammocks and all of them sleeping and snoring not only where they ought to have been, but in corners, corridors and anywhere space was to be found.

‘We were held up at Newcastle for almost an hour and if it hadn’t been for an ATS girl, I don’t know what I’d have done – you know what I mean …?’

No need to go into intimate detail, but the resourceful young lady had left the train, marched up to the engine driver and loudly threatened, ‘Now listen ’ere, mate! If you start your bleedin’ engine before me and this lady have found somewhere to have a widdle, I’ll burst yer!’ To which the driver replied that it looked as if they’d have time to sit there for the rest of the night and make their Wills if they were so minded, before he got the green light to move.

So embarrassing it had been and surely obvious to everyone awake that they were about to search the blacked-out railway station for the ladies’ room!

‘But wasn’t there a lavvy on the train?’ Tilda quickly sized up the cause of the upset.

‘There were several, and all of them filled with luggage.’ If she could have reached one, that was. They’d had the greatest difficulty getting off the train and they had struggled and pushed their way back to their compartment only to find their seats occupied by two burly sergeants who gazed at the ATS girl’s single stripe and told her where she could go. Pulling rank, Miss Clitherow later discovered it was called, and bleedin’ sergeants were always doing it!

‘And the train was dirty and blacked out.’ Except for the odd blue light bulb, that was, and if she never set foot on a train again for the entire duration of hostilities, it wouldn’t bother her one iota. And that, she supposed was something of a contradiction in view of the decision she had made.

‘Never you mind, Miss Clitherow, dear. Just take off your hat and wash your hands, then I’ll pour you a cup.’ Tilda had never seen the housekeeper so distraught, not in all her thirty-odd years at Rowangarth. ‘And then I’d get a bath, if I were you, and pop straight into bed.’

‘Oh, no!’ A bath maybe, but she must see her ladyship as soon as maybe, thank her for the time off, then explain the position fully, a thought which brought tears to her eyes and Tilda to place a comforting arm around her shoulders – a liberty she would once never have dreamed of taking – and tell her that she was home and safe now, and must never go away again. Which immediately caused the tears to flow faster and for Miss Clitherow to murmur, amid gasps, ‘Tilda! Please don’t say that!’

The tears came again when she and her ladyship were comfortably seated in the small parlour, windows wide to the July afternoon. It was her ladyship’s fault, the housekeeper reluctantly admitted, her being so genuinely pleased to see her back from her bereavement.

‘We have missed you, Miss Clitherow,’ Helen smiled. ‘It’s so good to see you again. Julia tells me your journey was very uncomfortable, but never mind – you are home now.’

‘Oh dear, Lady Helen, but I’m not you see. Well, not for so very much longer.’

And she had gone on to explain how her cousin Margaret – the elder sister of Elizabeth, whose funeral Miss Clitherow had gone to attend – had begged her, almost, to leave domestic service and spend her remaining years close to kin amid the beautiful – and safe – hills and lochs of Scotland. ‘It’s time for you to retire, stop working for the gentry, Agnes, my dear. And it’s so peaceful and quiet, here.’