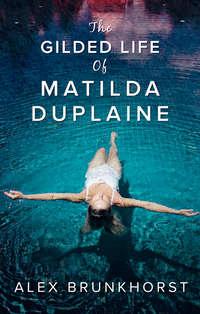

The Gilded Life Of Matilda Duplaine

Kurt walked in with a cup of hot tea on a silver tray.

“Did you have a nice time?” Lily asked.

“Yes, thank you so much for the invitation.”

“It can be a bit difficult being the seventh. Some say it’s unlucky, but I think you handled it very well. And it was delightful to have someone under the age of thirty around. I so rarely rub shoulders with youth anymore.”

Lily smiled approvingly, and I again noticed how attractive she was. It wasn’t that in-your-face kind of beauty Carole possessed. Lily’s father had been rich, so her mother had probably been pretty. That was how the world worked.

As if reading my mind, Lily leaned to her left and picked up a silver-framed black-and-white photo.

“If you haven’t decided on a photo for your story yet, this would be a delightful choice. My father adored my mother, absolutely adored her, and it would paint a much fuller picture of him than some snapshot of him at his desk running the studio.”

I studied the photo. Joel Goldman and his wife were walking down steps from a jet. Lily’s mother was so beautiful she could have been one of Joel’s starlets. She wore a raincoat and gloves, and a loose printed scarf knotted below her chin covered her head so only a bit of her blond hair showed. Oversize earrings dangled three inches below her ears. They were incongruous with the rest of the outfit, as if her jewels were a form of rebellion.

And her husband, he was big all over—big face, big blond hair, big eyes, big crooked nose, big presence and two hundred pounds of stone for a body. The only things wiry about Joel Goldman were his glasses. Despite his wife’s beauty, it was Joel who was the center of the photo.

In the background, behind the couple, was a guy I recognized as a much younger David Duplaine.

“When was this photo taken?” I asked.

“Eighteen years ago—give or take a year. When you’re my age they all blur. I only remember the really good or really bad ones—and sometimes not even those.”

“Is that David?” I asked, pointing at the figure in the background. David seemed to be onstage, but positioning himself just beyond the spotlight.

“Yes.” Lily smiled.

“You’ve known him a long time, then.”

“Over a quarter of a century. David was a hustler. He grew up in Queens and lied his way into a talent agency. He told them he graduated from college but he didn’t. In fact, David never much believed in the value of school. Education—that he believed in. David is the most educated man I know, but not through formal schooling.” Lily sipped her tea. “The agency found out, and he would have been fired had my father not made a phone call. David would have done well anyways, but he always thought that phone call saved his life. He can be so melodramatic—David.”

In fact, in a city that thrived on the theatrical, David was never portrayed as the dramatic sort. One of his films could bomb, a newspaper could win a Pulitzer, a television show could sweep the Emmys, and David would handle all three scenarios with the same stoicism.

For the first time I wondered if Lily was what we in journalism would call a reliable source. Or, conversely, perhaps Lily was right. Maybe David and the rest of them were always smiling for the cameras, but their real lives—the ones that took place in the dressing rooms of very expensive real estate—had nothing to do with their public personas.

To avoid Lily’s eyes I looked at the ivy. It was spotlighted, and its shadows played on the ceiling.

Lily, for her part, studied her tea. Its exotic scent combined with the smell of burned wood made me think of the Orient.

Lily took a sip of her tea before continuing, “David worked at the talent agency for a few years, and then my father gave him two million dollars to start his own production company. He had the magic touch, as they say in the movies, and a few years later the company was rolled into the studio—and David made the transition to running it. And the rest is history.”

“That was quite the gamble. For your father, I mean.”

“All great businessmen are gamblers in one way or another. My father was no exception. Many of his leading ladies had never been in a picture before. He’d take a chance on a girl if she had je ne sais quoi. He optioned a screenplay from his driver that became one of his highest-grossing films.” Lily’s green eyes traveled far away. “In fact, my father loved to gamble, but his vice wasn’t the stock market or the horses. It was people.”

“It doesn’t sound like a vice if he won.”

“Generally, but not always. Sometimes the house wins,” Lily said distantly. “And how about you, Thomas Cleary, are you a gambler?”

I hadn’t thought of it before. But now I considered Harvard—how I had got there. And Los Angeles—how I had crawled out of the rubble of my life to end up at one of the most prestigious papers in the country. And then there was Willa. By pedigree I should have been a member of her staff, but instead I had spent years with her heart resting—precariously, it would turn out—in my palm.

“Yes, I guess you could say I am—a gambler.”

“I could tell, the moment I met you. Midwesterners are typically horribly risk averse, but I pegged you for the type to throw your chips down,” Lily said with what might have been a glint in her eye. “What was your biggest bet?”

“I gambled on a girl.” I thought again of Willa, who even years later never traveled far from my thoughts. I pictured her vividly the afternoon we had first met in Boston, propped on her elbow on a blanket beside the Charles River.

“And you lost, I’m assuming.” Lily raised an eyebrow while blatantly looking at my ring finger and bringing me back to the present.

“You could say that.”

“Was she a Harvard girl?”

“Yes, originally from Manhattan.”

“Which part?”

“Fifth Avenue.”

Lily smiled wryly. “Girls like that are trained from a very young age to break the hearts of sweet men like you.”

“You should have told me earlier. It was an expensive lesson,” I said. “It drained my emotional bank account.”

“At least your financial bank account is still intact. It could be worse.”

“I’m a reporter. My emotional bank account will always be more plentiful than my financial one, and if it’s not, then I have a problem.”

Lily smiled. “Don’t take it personally, love. You’re a tremendous catch, but even the biggest bass isn’t a prize for a girl who has a taste for caviar. And who knows? Perhaps someday you may discover your loss was a win in disguise.”

Lily’s eyes traveled to a spindly plant. She stood up and picked a dead leaf out of its pot. She placed the leaf on a side table.

“You must be exhausted,” Lily said, before returning to her chair.

“I am, actually,” I said. My adrenaline level was still so high it could have been 10:00 a.m. but I just now remembered my deadline, and I couldn’t count on Rubenstein to extend it another minute. “And I have a story to write.”

Lily walked me to the front door. When she opened it, the purr of the Mercedes greeted us. Kurt held the rear passenger door open. I wondered how long he had been standing there.

“Oh, I almost forgot,” Lily said, excitedly. “Wait here.” She disappeared and then returned with a large wrapped box. “This is for you.”

“I couldn’t possibly,” I began.

“You could possibly,” she said. “My only request is that you open it when you get home because I get embarrassed when people open gifts in front of me.”

The look on Lily’s face said there was no arguing, so I accepted it.

“Thank you for everything. What an evening,” I said.

“You’re welcome. Good luck with your story. My father was a luminary in this town, and I would like him to be remembered as such.”

By the time I got home it was past midnight, and I had to crank out my article by seven to get it to editorial. My one-bedroom apartment had always seemed humble, but now, after where I had just been, I realized it was downright pathetic. It was smaller than Lily’s living room, and the dirt was embedded so deep that not even a few coats of paint could do the trick. Appliances were decades old, the furniture was mine from boyhood, and the ceiling was covered with asbestos rather than ivy.

I was an adult, but my apartment was a college kid’s. Bel-Air was too grand for a man like me.

I wrote my article on Joel as quickly as possible and emailed it to the office along with a scanned copy of the photo Lily had given me. I was about to slip into a catnap before work when I remembered the package.

I unwrapped it to find a box from one of Los Angeles’s most expensive boutiques. Inside were two perfectly creased shirts and trousers folded in tissue paper. There was no note.

Four

Phil Rubenstein looked as if he had crawled his way out of the pages of a hard-boiled detective novel. He was what you’d call a guy’s guy. There was a beefiness about him, and he had a ubiquitous five-o’clock shadow at any time of day. Although I never had the privilege of going to lunch with him, everyone who did came back with bloodred drinker’s eyes and speech that sloshed around in their mouths. For Rubenstein the two-martini lunch was a restrained one.

It was Phil Rubenstein who had hired me as a reporter at the Times a few years earlier. To say I was at the lowest point of my life back then didn’t do the situation justice. I had been unceremoniously fired from the Wall Street Journal for an act of plagiarism I didn’t intend to commit. That came after my girlfriend of two years had left me—equally as unceremoniously, with barely a phone call. I was broke, jobless and alone in Manhattan.

My job search went poorly. I was told time and time again I was unemployable—not only in the field of journalism, but in any field. After months of futilely applying for jobs, big and small, a college buddy’s father called his chum Rubenstein on my behalf. There were favors owed somewhere or another, and Rubenstein had taken a liking to me, so I ended up at the Los Angeles Times.

Because of that, I always held a soft spot in my heart for Rubenstein. In fact, whether by exaggeration or not, I considered the man my savior. Never mind the fact that immediately after hiring me he seemed to forget I existed. The newspaper business in Los Angeles was like the film business—it was about who you knew, and that column was blank for me. The well-connected guys got invited to the premieres, club openings and parties, and got all of the scoops that went with them while I had got the smallest local stories.

“Cleary, get in here,” Rubenstein shouted across the pit.

Phil Rubenstein never called me into his office, and the other reporters made eye contact in the way grade school students do when they sense one of their peers may be in trouble.

I temporarily abandoned the story I had been researching on the heated council race in District 10 and made my way across the sea of accusatory eyes before arriving at Rubenstein’s corner office.

The office was the low-rent generic kind that newspapers with shrinking budgets and insolvent balance sheets tended to have, but Rubenstein had personalized it. Photos of Rubenstein with various studio heads and actors dressed up a stock credenza. Framed movie posters with handwritten notes covered the white walls. He had a plastic statue that looked like a fake Oscar award that said #1 Boss. Rubenstein was a newspaper editor, but judging by his office he seemed to think he ran Twentieth Century Fox. This was not by accident.

“How you feeling this morning, Cleary?”

The truth: I had a headache that threatened to become a full-blown hangover if you blew on it wrong, and I could still taste the stale Grey Goose and lime juice on my tongue.

But it was an extraordinary night that had caused this crappy state to begin with, and the headache made me feel as if the night before was somehow still alive.

“I feel good,” I said, opting not to go into detail, satisfied with the fact that my story on Joel Goldman had run on the first page of the Calendar section. There was only one front page of Calendar and it was a daily jostle to get there. The death of one of the most famous titans of the entertainment business was certainly significant in its own right, and I had frosted the story with quotes from David Duplaine, George Bloom and Carole Partridge—three of the industry’s hottest commodities.

Rubenstein gazed out his office window. “Your story was good, Cleary. And the quotes were all nice touches. Overkill, but nice. The only time I’ve seen all those names in one place was at the Oscars.”

“Glad you liked it.”

“That thing with the Journal aside, you’re a very good writer. One of our most talented.”

“Thanks,” I said, wincing at the mention of the Wall Street Journal as one might cringe at a chance encounter with an ex-lover on the sidewalk. I felt a bead of sweat race down the back of my neck.

“I need something from you,” Rubenstein demanded. “I hear there’s going to be a major shake-up at Duplaine’s studio. I need you to call Lily Goldman and get the story. I want it to break here, at the Times, instead of one of those shitty internet sites or, God forbid, the Reporter.”

If Phil Rubenstein had asked for my firstborn, I would have handed him over with a year’s supply of diapers. That said, I had no connection with Lily Goldman. Lily had invited me into her circle for a few hours solely for the purpose of putting her father back on the front page, which I’m sure she felt was his right. The shirts and pants were a thank-you gift, significant to me but probably paid for through Lily’s petty-cash account.

At the thought of the word pants I looked down at my lap. An iron crease cut my thigh in half, lengthwise. I flattened the pants out with my palms as if Lily were peering over my shoulder.

“I don’t think we have that kind of connection. Lily and me,” I added, when Rubenstein let the silence linger.

“We’re getting trumped on everything—all of it,” Rubenstein finally said, more to himself than to me. Out the window, a combination of heavy fog and smog was rolling in. The tops of the buildings had disappeared. “Do you know how many Pulitzers the Times has won?”

I shook my head.

“I don’t know, either, but a lot,” Rubenstein said. “Otis is rolling in his grave watching this state of affairs, banging on the cover of his coffin, begging to come out before we go the way of the dinosaur.”

His remarks on Otis Chandler, the paterfamilias of the Los Angeles Times, might have been an exaggeration, but the dinosaur bit was true. It wasn’t just us—it was all printed newspapers.

“You know Lily better than I do,” I said. “Why don’t you just call her?”

Rubenstein turned around. “She invited you to a dinner party at George Bloom’s—within minutes of meeting you.”

“Because she wanted quotes for her father’s story. She wasn’t exactly looking for a new buddy to have beers with.”

“I really want this one, Cleary.”

I looked at Rubenstein and saw something vulnerable in him. This was the man who had saved me from Milwaukee, where I probably would have been working beside my father in the lumber department at Menards.

“I’ll call her,” I said.

* * *

I cleaned my desk, filed a pile of old documents, scrubbed my spam folder, made my twice-weekly call to my dad a day early and did almost everything except call Lily.

There were myriad reasons for this procrastination, but top on my list was that the night was still untainted. Once I called Lily and she refused to help me out, I would go back to covering freeway expansion plans and a dull life in a modest apartment.

The only way I knew to reach Lily was through her shop, and once the clock had struck four I knew time was running its course. I had savored the night, and now there was work to do.

Ethan answered the phone on the fourth ring. I imagined him staring at the phone beside him, waiting a moment to pick up because Lily had probably instructed him not to appear too eager. I was told Lily wasn’t available. When Ethan inquired if Lily would know the purpose of the call I answered in the affirmative, and then I hung up quickly, before he had time to ask anything else.

* * *

Three days passed and Lily didn’t call. I couldn’t say I was particularly surprised, but I would be a liar if I didn’t admit the slightest bit of disappointment. Interestingly, the Duplaine story didn’t break—at the Times or elsewhere—and all was quiet from Rubenstein’s office.

As for the evening, it was like anything else in life; the farther one gets away from it the smaller it appears. What had initially seemed like a life-changing event became less consequential as days passed. The first night, I fell asleep hard on my back, and I dreamed of the leopard cat, tame under Carole’s palm and wild in the outdoors. The second day after, which I now remember as a day of waiting for my phone to ring like a schoolgirl waits for a call from a crush, I found myself thirsty for gimlets on ice and I longed to dive into the Blooms’ swampy swimming pool and swim with the minnows. By the third day I realized that the night that meant so much to me meant nothing to them. I was a mere reporter.

The upside of the dinner, however, lingered. Based on my Goldman story and the possibility of the Duplaine scoop, Phil Rubenstein had given me a decent assignment on the weekend box office, and I was typing it up when the phone rang.

“Cleary here.”

“Thomas, love. It’s Lily.”

My heart beat a bit faster, and I found myself straightening my spine.

“Lily, what a surprise.”

“Oh, I know. I do apologize. I meant to phone you back sooner, but work caught up with me. I had to fly to Aspen unexpectedly to pick out some wallpaper for a house and the jet lag has just about killed me.” I was about to remind Lily that Colorado was only one hour ahead of Pacific Standard Time, but then let it pass. “I must say, I absolutely loved your little story on my father. It’s been so long since he got press. He adored reading about himself in the papers.”

“I’m glad you enjoyed it.”

I heard the antique servant bell announce a visitor in the background.

“Oh dear, that’s a customer—and a dreadful one at that. Let me cut to the chase. I spoke with David this morning and he mentioned he’s making some personnel changes at the studio. I convinced David he should give the exclusive to you instead of that absolutely horrible Blaine Wyatt at the Reporter.”

Professor Grandy’s Journalism Rule Number Three: If a story’s handed to you on a silver platter, it’s either not worth eating or will cause food poisoning later on.

“I’ll be right there, Ethan,” Lily called into her store. “David’s assistant’s name is—” She paused. “Oh, I can’t remember now. I’m terrible with assistants. I know you’re busy, but take a minute to call David’s office and get the information. I think you’ll find it worth your while. They’re expecting you.”

“Thank you,” I said, trying to restrain my excitement.

“You’re welcome. Oh, and how rude of me. I haven’t stopped talking, have I? Did you need something the other day? When you phoned?”

I smiled. “I just phoned to say thank-you for the incredible evening and the overly extravagant gifts.”

“Midwestern manners. I should have expected nothing less. You’re more than welcome. It was lovely to have you. Now do call David’s office and let me know how it goes. Au revoir.”

There was a fumbling of the phone, and then the line went dead.

It took a few calls to get to the story, but once I did I was rewarded not just with personnel changes, as Lily had underestimated, but with the untimely firing of the president of the studio, who had been misappropriating corporate funds on private jets, award show after-parties, dresses for his wife and suits for his lover. I got to work, writing well into the night, pausing only to steal a quick cigarette on my balcony.

It was 1:00 a.m. I took a long drag of my cigarette and craned my head toward the hills. That sliver of a view of the mountains was the only reason I had gotten this crappy apartment in Silver Lake in the first place. I couldn’t even remember how I’d gotten here anymore, except for the vague fact that around three years ago I headed out to Los Angeles from Manhattan. It was supposed to be a temporary apartment—a stop on the way to greatness, someplace I would eventually point to and say, “Can you believe it? I started out there.” It didn’t happen that way. I would have left but for the fact I had no place to go.

I looked around me. It wasn’t close to being Christmas, but icicle lights hung on my neighbor’s balcony, and pot smoke wafted from his apartment day and night. Tall date palms stood high and mighty in the distance, but the foliage in our complex was the indigenous sort that required little water or sun. The U-shaped building was centered on a dilapidated courtyard. There was a sadness to it, because in the 1950s when the building was built someone had tried to make something pretty, but now the courtyard was neglected. Chairs with webbing too thin to sit on were sprinkled haphazardly around a swimming pool. The pool needed a new heater, and the hot tub was drained. Peeling plaster gave the water a cloudy and gray appearance.

I surveyed the surroundings one last time before crushing the remnants of my cigarette into the stone balcony. I had a deadline to meet.

Five

The story, in various incarnations, stayed on the front page for the next four days and then got mileage in Calendar and Business. We had scooped the Reporter, ditto for the online sites that were breathing down Rubenstein’s back. The story was covered by nearly every national publication—the New York Times to the San Francisco Chronicle—and I gathered them up and savored the words “The Los Angeles Times reported...” because the Los Angeles Times meant me. I knew the story and the scoop had nothing to do with me. Any community college journalism student who happened to have landed at the right place at the right time could have written the same article, but I was proud nevertheless.

I grew up in Milwaukee, the land of gratitude and manners. So I knew a token thank-you to Lily was in order. Choosing a present that I thought Lily would like was difficult on a reporter’s salary, so I did the best I could. I went to the most expensive department store in the city and chose the least expensive item there: a candle.

As I made my way over to the shop I thought of how quickly my prospects had changed. It had been just over a week since I had first met Lily.

The bell announced my arrival. The store was as cluttered as on my first visit, and it took a moment for Lily to emerge from behind the large Asian screen.

“Thomas! How are you, love?”

“Fine. I hope I’m not interrupting.”

“You could never be an interruption. What’s this?”

I looked around and became conscious of the candle I was carrying. Suddenly it seemed like a totally inappropriate gift. In my weeklong sabbatical I had forgotten how exotic and remote the world of Lily Goldman was.

“Nothing—”

“A candle,” Lily said, unwrapping it lustfully. “I absolutely love candles. It’s the most exquisite color of vanilla, isn’t it, Carole?”

It was only now that I noticed Carole lounging on a sofa, surrounded by pillows in various textiles and prints. She lay on her back, barefoot and beautiful as she had been the night of our first meeting. She looked as if she belonged in Marrakech or Casablanca, not in an antiques shop in Los Angeles.

“Truly a one of a kind” was her response. Her delivery was as polite as the sentiment was sarcastic.

“Carole’s here looking for pillows for her aviary,” Lily said. “This candle is absolutely spectacular, Thomas. You are so sweet. Isn’t he sweet, Carole?”