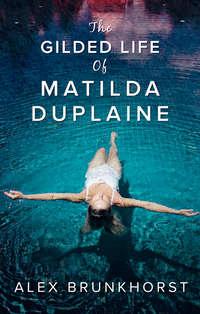

The Gilded Life Of Matilda Duplaine

“Did you find anything?” I addressed both of them. I had no idea why one would need pillows for an aviary, or why one would have an aviary in their home in the first place, but I needed to quickly steer the subject away from the embarrassingly cheap gift.

“My first indication was to use this peacock fabric—” Lily pointed to an ornate fabric with stenciled peacocks, seemingly a perfect fit “—but now I feel it’s too predictable. I deplore predictable.”

Carole glanced at the peacock fabric with indifference, as if there was nothing about it that compelled her either way, and then she focused on her lap, at a script that lay open to a page somewhere around sixty.

“Your article on the terrible man who worked for David was brilliant,” Lily said, addressing me. “You are a fantastic writer, Thomas. Isn’t he, Carole?”

“He handled a tricky situation with aplomb,” Carole replied, flipping the screenplay’s page.

It was true. I hadn’t lambasted David as some of our competitors had. Instead I was deliberately gentle, exonerating David of blame while still maintaining my journalistic integrity. It was a strategic move on my part of course. I had to protect my position in their world, and it still felt very precarious.

Lily disappeared into rows of hanging fabrics, and I was left alone with Carole. I opened my mouth to say something, but words failed me. Carole, on the other hand, appeared to almost revel in my discomfort. We sat like this for a minute or so, and then I turned my back, pretending to stoke a newfound interest in Belgian linen.

Lily returned a few seconds later, her face registering the stony silence that hung in the air. “Nothing appropriate. Maybe I’ll paint something later.”

Carole stood up and slipped on her shoes, throwing the screenplay into a large purse. Then she kissed Lily on the cheek.

“Don’t go,” Lily begged.

“Are you forgetting I’m cohosting a dinner for seventy tomorrow? I wish I could go off shopping all day, but help requires such micromanagement. And so does David.” Carole sighed.

Lily turned to me. “David and Carole are cohosting a little event for the governor at David’s. Thomas, I have a glorious idea. Why don’t you come?” she said enthusiastically.

I wished Carole would step in and second the invitation, but she didn’t. Instead she preoccupied herself with a screen that featured oxen in repose in a meadow, rubbing her fingers over its surface. Her fingernails were painted a shade of olive, and I wondered if the odd, almost grotesque, color was chosen for a horror-movie role or if olive was the new red.

“I couldn’t,” I said, as transparently as possible.

“Of course you could. Carole, do tell Thomas he should come. Insist he should come. It would be good for you at the paper, Thomas.”

“Lily’s right. You should come, Thomas. I’ll have Adrian add a seventh to our table.” Carole said it blandly, and I knew that Carole’s word choice was deliberate. Seven not only had an unlucky connotation, as Lily had pointed out, but it also called for a lopsided table arrangement. I could already imagine Adrian, whoever he was, silently cursing me, the nettlesome seventh.

Carole’s invitation was disingenuous, and I should have turned it down. Instead I allowed it to hang there. I wanted to jump into their lives again—why, I didn’t know.

“Well, it’s decided, then,” Carole said. “We’ll see you tomorrow evening, eight o’clock sharp.”

Carole put on a large floppy hat and oversize sunglasses that rested low, almost on the tip of her nose. Outside, a black SUV waited for her, and a driver opened the rear passenger door expeditiously. In ten seconds the car was gone, and a minute later the paparazzi were too late.

Six

I knew I wanted to go to Harvard when I was ten years old. Harvard was a quixotic dream for someone raised in Milwaukee’s gritty public school system, but that dream became my driving force.

When I was twelve I figured out that it was speed that was going to get me there. My talent for the five-thousand meter blossomed suddenly, without warning. Early in the morning, before the sun came up, I could be found running beside my father’s stopwatch. My dad had barely received his high school diploma but he would come to share my dream.

This singular intensity propelled me to shatter every state and Harvard running record. It was that same stubborn determination that made me ignore the small fact that Carole didn’t want me to attend the fund-raiser. I had got a taste of wealth and power, a mere whetting of the tongue, but I wanted more.

Had I turned down Carole’s noninvitation I would have been at the paper, working on a plum story handed to me by Rubenstein, much to the chagrin of the senior writers. Instead, the following afternoon when my phone rang I found myself at a mini-mall in Westwood renting a tuxedo for what promised to be the fund-raiser event of the season.

“Cleary here.”

“Millstone was found dead in his loft in SoHo.” It was Rubenstein, and he was referring to a young, up-and-coming A-list actor. “I know you’re going to the fund-raiser tonight, but you need to crank out a quick web piece.”

“But—”

Rubenstein hung up.

I headed back to the paper, aware that it was nearly impossible for me to get out a story and make the dinner on time. I considered calling Lily and canceling but opted against it.

* * *

Five thirty.

I went back to the office to find Rubenstein had lent me an intern to pull together research for the story on Millstone. I paged through his notes. Interns were known to be overzealous: in this case, the guy had pulled quotes from Millstone’s eighth-grade teacher in Australia, his tattoo artist in Brooklyn and the sandwich maker at the deli he frequented, but he neglected to get quotes from the costars or producers of his new film.

By six o’clock I had edited most of the research and typed my lead. I had called in a favor to George’s office to get an additional quote from the producer of Millstone’s new film. In turn, the producer—with the understanding that I was a chum of George’s—gave me the private cell phone number of Millstone’s publicist, who gave me the first on-the-record quote about the tragedy.

Around six thirty, I finished my story and emailed it to editorial. I was in such a hurry I started shedding my clothing in the hallway, and I finished changing into my tuxedo in the restroom a few seconds later. I glanced at myself in the mirror. Even in the harsh fluorescent light I seemed presentable enough. The governor. A grin broke through my stoicism.

On my way out I looked up at the wall clock in editorial. It was set to precision for deadline’s sake, and it was precisely six forty-five.

I descended the concrete steps two at a time and sprinted to my car. Sunset Boulevard was jammed, and when I finally saw the words Bel-Air lit up in that eye-blinding shade of ice blue, I exhaled. It was only seven-forty. I had twenty minutes on my side. I drove leisurely through the road between Bel-Air’s pillars and mimicked Kurt’s serpentine drive to the Blooms’ before taking the final hairpin turn that led to David’s estate.

I immediately knew something was wrong. There were no signs of a political party—or any party for that matter. There was no security detail, no guards, no music, no catering trucks. The estate was quiet.

I rang the bell on the towering gates protecting the property, but there was dull silence. I heard only the branches of a sycamore tree shimmying in the unseasonably cold fall winds. Lily had definitely said the party was at David’s. Kurt had also double-confirmed that the party was this evening. I pulled my phone from my pocket, but I had no cell service.

I had two choices: drive to Sunset Boulevard to call Lily or use the phone at David’s estate. I rang the bell again before eyeing a ficus hedge that had to have been five times as tall as me.

Panic started to set in. Lily Goldman was a shiny lucky penny in my pocket, the first talisman in a long time I had managed to pick up and secure in my palm, if only briefly. I imagined her this very second, fielding questions as to my whereabouts from the other five guests while she fingered a ruby ring or ivory necklace. I also thought of Carole, eyes heavy with exasperation, instructing the staff to remove the seventh chair that had been so craftily squeezed into the table for six and exchanging an “I told you so” glance with David, his thick eyebrows coming together in agreement.

Tonight was supposed to be a glittering star of a night. Not only was I going to meet the governor, but I was more determined than ever to make a career comeback. Suddenly, with the Goldman story and the Duplaine piece, I had begun to feel as if the future was once again full of possibility. I had always intended to return to Manhattan in glory, to triumph over what had happened there. Possibly it was a pipe dream—it had only been two big articles after all—but I was hoping the trail of plum stories was leading me east.

“Fuck,” I said out loud, still not comprehending where I could have gone wrong.

I backed my car out from David’s impenetrable gates and parked it on a patch of gravel on the side of the narrow road. I rolled down my window, and that was when I heard it.

In the distance was the faint, familiar sound of a tennis ball. There was an oddly regular rhythm to it: pong, pong, pong, quick pong, slow pong, pong, pong, pong, quick pong, slow pong.

I got out of the car and walked over to the side of David’s property, where I saw a shot of fluorescent white light through the trees. I remembered that during our long drive toward the estate we had passed a gate covered in ivy. Behind it must have been a tennis court.

I crept closer, facing a stone wall that could have fortified a federal penitentiary.

“Hello,” I shouted, but the word got caught in the wall. “Is anyone home?”

There was no answer, though there was definitely someone home.

It was then that I noticed an oak tree weeping over David Duplaine’s wall, and I glanced at the lowest branch. It would have been a reach for most men, but I was tall and I had had plenty of practice climbing trees during those muggy mosquito-filled summer days of my childhood in Wisconsin. Even in dress shoes, navigating the tree wasn’t particularly difficult; I conquered one branch after the next, giving me a feeling of satisfaction I hadn’t felt in years.

I scaled half the oak tree and then paused to catch my breath.

My first sight of her was from the back. She stood at the baseline of a red-clay tennis court surrounded by trellises thickly covered with ivy. Her long limbs were tanned golden-brown; but they were coltish, as if she didn’t quite know how to work them yet. It could have been my distorted perspective from above, but she appeared around six feet tall. Her blond ponytail reached the middle of her back and was tied together with a white satin ribbon. Indeed, she wasn’t dressed for practicing serves at all, but for a match at Wimbledon. Her white dress had a bunch of froufrou on it—frills, lace—and it was so short her ruffled tennis panties peeked out from beneath it. The Nike shoes she wore looked brand-new, save for the stain of clay near their soles.

Her ritual was exact: first she chose a bright yellow tennis ball from a hopper, searching carefully for just the right one. Then she situated her shoe at the corner of the baseline tape and the center mark. Finally, she bounced the ball three times, tossed it in the air to the exact one-o’clock position, and served it with a motion so fluid it was the stuff of physics textbooks and tennis academies.

All this exactitude resulted in a beauty of a serve that rivaled those on the professional tour and sent a ball with laser precision into one of the orange cones that sat in the corners of the service box as targets.

This ritual repeated itself eight times until the hopper was drained of balls.

I had grown up around the sport of tennis, so the sight of a girl in a tennis dress embarking on service practice was in itself not particularly interesting. But the scene was captivating in the way that a movie may hold your attention so intensely your real life vanishes.

I could not avert my eyes.

The girl walked over to a viewing pavilion, a plush mini Palladian palace. Silver pitchers, a silver ice bucket and crystal glasses sat on a silver tray on an antique table. She plucked ice out with silver tongs and placed it in one of the glasses, and then she poured water from the pitcher into the glass until it reached the glass’s equator.

She then took a few sips of the water, surveyed the littered balls and made her way back out onto the chilly court. She picked up the hopper and started collecting the bright yellow tennis balls, but she struggled to line the hopper up to push the balls through its rails. For a girl who could serve a hundred miles an hour, it was odd she moved so slowly on this remedial task.

The girl started toward my side of the net, and I took my opportunity.

“Excuse me,” I called down from the oak tree.

The girl stepped backward quickly and looked around, trying to discover where the voice was coming from.

“It’s okay. I won’t hurt you. I’m up here, in the tree.”

She looked up, startled, and for the first time I could see her face. She was a woman, but there was a childlike quality to her. It was difficult to peg her age, but I would have bet she was around twenty. There was something very “heartlike” about her—the wide shape of her face, the cheekbones so high and full they went almost to her eyes and the delicate nose reminiscent of an arrow. It’s hard for me to say now if I would have called her classically beautiful, but she was that star in the sky that you can’t take your eyes off, even if it’s surrounded by brighter ones.

She continued to study me, perplexed. I didn’t know what was stranger, a girl dressed for Wimbledon practicing serves alone at night or a guy dressed in a tuxedo sitting in an oak tree.

“Why, what are you doing up there?” she asked.

“This may sound strange, but I thought I was going to a fund-raiser this evening at Mr. Duplaine’s house,” I said. “I’m a friend of Lily Goldman’s. I tried phoning the gate, but no one answered. And—” I paused. “And. Well, is anyone here?” I finally asked.

“No, there’s no one home,” the girl said. Her voice was soft and melodic.

“Is there supposed to be a party here?” I asked.

“It’s at the other house—the one on the beach.”

“Do you have an address?”

“I’ve never been there, myself, so no, I have no address. It’s in Malibu, I believe, but unfortunately there’s no one I can even ask. You must think I’m incredibly unhelpful but I’m not meaning to be.”

Malibu was about forty-five minutes away with favorable traffic conditions. So at this point I still had time to climb down the oak tree and call Lily for the address. I could have made it in time to meet the governor, to sip a gimlet while overlooking the gentle, rolling waves of the Pacific. But instead I said:

“You have quite the serve.”

“Thank you. My coach says the same thing. One hundred fourteen miles an hour. I got a radar gun for my birthday.” She said it with gushing pride and pointed to a black contraption set up in the corner of the court. On the screen, 109 MPH registered in red, digital numbers.

“When’s your birthday?” I asked.

“The twentieth of April.”

“A Taurus.”

“A what?” she asked.

“Astrology. Do you follow it?”

“Not only do I not follow it, I’ve never even heard of it.”

I paused, wondering if the girl was kidding, but I didn’t detect a note of sarcasm in her voice.

“I’m from Milwaukee—we don’t believe things like that there, either. It’s all hocus-pocus if you ask me.”

“Milwaukee’s in Wisconsin. Wisconsin’s capital is Madison. Its state bird is the robin and it’s known as the Dairy State because it produces more cheese and milk than any other state,” she said, as if reading from a teleprompter. “This thing called astrology—what is it exactly?”

“That’s a good question,” I said. “It has something to do with the stars. I’ve never really understood it, either.”

“You mean astronomy, then?”

“No, they’re two different things—astrology and astronomy.”

“So what are you in astrology terms?”

“A Scorpio.”

“A scorpion. In other words, you’re an eight-legged, venomous creature to be wary of?”

Her tone was deadpan.

“No poison here, just a nice guy from Milwaukee.”

She let out a big, jovial laugh.

She was a curious creature, and I was intrigued. Her manner of speech was officious and old-fashioned. She was interested and reserved, insecure and confident, coy and bold. She was unlike anyone I had ever met.

I looked down at her again and realized she was gazing at me with wide-eyed curiosity, too. The tennis court lights made her eyes glitter.

I wanted to see her up close.

“I play tennis—well, used to play tennis. I haven’t in years. Do you want to— Maybe, would you like to play sometime?” I said with the insecurity of a fourteen-year-old asking a girl to a Friday-night dance.

She paused.

“Oh, I don’t think so,” she said sadly, as she traced the W on the tennis ball. “Thank you, though, for the offer. It was kind of you.”

It’s difficult to judge oneself with objectivity, but my whole life I had been told I was a good-looking guy. Sure, I didn’t have that well-oiled slickness the other guys at Harvard had. They had Wall Street money, last names with a familiar ring to them and country houses. They were gentlemen who knew what wine to order, gentlemen who winked more than they smiled and gentlemen who could sell you something you didn’t even want. Women loved them for all of it.

My appearance was more of the homegrown variety: I had inherited my father’s height, broad chest, strong jaw and blue eyes, and I had my mother’s oversize smile and blond hair that looked a touch red when the sun hit it right. I looked like the kind of guy who would run his wife’s errands and coach his kids’ baseball team, all while hoisting this year’s corn crop to the farmer’s market. In high school, girls had liked me; in college they had called me “cute,” but I wasn’t husband material. Marriage for those girls was a game of Monopoly. They wanted the most valuable real estate, and anything less than Central Park West wouldn’t do.

But in all of those years, with all of those women, I had never been shot down so directly before.

A story, a date, a friendship, whatever I thought I wanted, whatever she thought she had turned down, it didn’t matter. I made the boldest move since I had moved to Los Angeles: I climbed down the oak tree to the stone wall, slid onto the viewing area canopy, then hopped down to the court, with leaves in my hair and a tear in my tux from the canopy spear.

We almost touched. In such close proximity I saw that sun freckles sprinkled her nose and her eyes reminded me of Emma and George’s leopard cat’s. They were green with black speckles, as if someone had spilled ink on them by mistake. She wore a tennis bracelet with diamonds that I knew enough to guess were two carats each. Plump diamond earrings covered her tiny earlobes. Jewels like this were generally kept between armed guards, not worn for tennis practice.

We stared at each other. I wasn’t going to Malibu.

“Why don’t we play for a few minutes?” I said. “It would feel good to hit the ball around.”

“I’m not so sure that’s a good idea,” she replied.

As a guy, it was my job to find an open window when a girl closed a door. I found a slight crack here—in her unsure inflection, her avoidance of eye contact, her choice of syntax.

So I climbed through the proverbial window. Five rackets wrapped in cellophane sat on a bench beside the court. I unwrapped one, took off my shoes and walked to the other side of the net.

I had played tennis in high school and, despite some rustiness, would have considered myself a good player. I rocketed in a pretty decent first serve, but before I had time to admire it she had nailed a backhand return that hit the place where the baseline met the sideline.

“Wow, good shot.”

“Thank you,” she said.

My next serve was a nasty topspin down the middle, and once again her return skidded off the baseline.

Twenty minutes later the first set was over. I had won a mere five points.

I walked up to the net, and she followed suit. She put out her hand proudly to shake mine.

“I’m now 1–0,” she said, glowing.

“1–0?”

“Yes, one win and zero losses. Still undefeated for life.”

“You’re meaning to tell me this is the first match you’ve ever played?”

“Correct.”

“Your entire life?”

“The whole of it. I only practice,” she said, her victory still covering her face.

“How often?”

“Three hours a day.” She paused, contemplating what was to come next. “Do you like cookies?” she asked as she headed toward the tennis pavilion.

* * *

The tennis pavilion was more elaborate than most houses. Ivy crept up the walls and partially hid glass casement windows. Reclaimed wood covered everything. I had the feeling this wood had been to France and China and back—all before the eighteenth century. A seventy-five-inch television screened a muted Gregory Peck film. An old stone mantel stood six feet high, covering a brightly burning fireplace below, surely crafted before the advent of central heating systems. Silver pitchers of lemonade and water sat beside crystal glasses. Six varieties of cookies were symmetrically lined up on trays, and towels floated in steaming hot water. Every provision was taken care of.

“Lemonade?” the girl asked.

“Sure. Thanks.”

She poured me a glass of lemonade to the brim and then put on a short satiny jacket that must have been the companion piece to her dress because the frills matched. Beads of sweat rested in the nape of her neck like seed pearls. She didn’t wipe them off.

A bowl of pineapple sat in a crystal bowl. The fruit was diced into equally cubed pieces, small and dimpled like playing dice. The girl plucked out a piece of pineapple with a fork, holding it up so the fruit dazzled under the soft light in the pavilion.

“Can I interest you in a piece of pineapple?” she asked.

“Yes, please. Pineapple’s my favorite fruit.”

“Mine, too,” she exclaimed with great enthusiasm, as if she’d just discovered that we had the same birthday or the same mother.

She slowly placed the fork in my mouth, and I tasted a few drops of its delicious juice before the entire cube of fruit went in. It was sweet, perfectly ripe. I pictured the farmer in Hawaii leaning over fields of pineapples, picking just this one, for just this girl.

She stared at me long after the pineapple had made its way down my throat. I was accustomed to being the observer, but in this case I was clearly the observed. Surprisingly, it felt nice.

The girl sat down and motioned me toward an antique leather chair beside hers. On the wall between us hung a modern painting of a lawn full of sprinklers. It was an image I recognized from art history books as a David Hockney. I assumed the painting was an original.

“I can’t believe you beat me 6–0. I didn’t give a good first impression,” I said. “Do you know what a 6–0 set is called?” I asked.

“No.”

“A bagel. Because the zero is round like a bagel.”

She smiled grandly, and I noticed she had great teeth. They were a bit crooked, but in a good way.

“I’m Thomas, by the way.” I made a long-overdue introduction. “I should have probably said that earlier, right?”

She didn’t introduce herself in turn. She took a long sip of lemonade with mint leaves.

“You should really think about playing in some tournaments. I think you’d do really well,” I said.

“You do?” she asked, leaning closer.