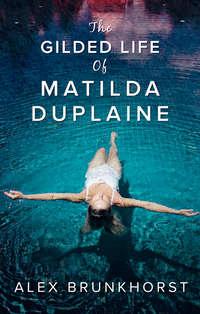

The Gilded Life Of Matilda Duplaine

“Yes. You seem the competitive type.”

“Is that a compliment?”

“I like girls with chops, so yes.”

“With chops?”

“Yeah, with chops.”

“I don’t know what that means, but I hope it’s a good thing. And I’ll think about it—the tournaments, I mean. I don’t think I’d be very good at losing. Are you good at losing?”

“No one is,” I said, taking a sip of my lemonade. “I’m surprised your coach doesn’t encourage you to play matches.”

She stared into the distance, where David’s grand white house loomed. We could only see its six chimneys—but it was there, in the background, bigger than us.

“My coach would like me to, but it’s complicated.”

She looked toward her yard, as if a missing puzzle piece lay somewhere in that rolling acreage. But wait, was this even her yard? I was so mesmerized that I hadn’t considered this question. Even in a city obsessed with dating young she was too young to be David’s lover. And if she were, wouldn’t she have been at the political event?

The girl focused her gaze on me—first on my hair, then my forehead, then my nose and then my mouth. She moved lower, studying my body obviously and examining the barrel chest of my torso and the calves that I had spent my boyhood covering up because they were too brawny for the rest of me. She eventually settled on my jaw.

“You have such a nice jaw,” she said sweetly. “It’s a man’s jaw.”

I smiled and found myself blushing.

“Thank you. It’s my father’s jaw. I grew up hating it. It was too big for the rest of me.”

“But now you love it I bet.”

“I grew into it. Now I tolerate it.”

She smiled. She then rubbed the back of her right hand on my reddish-blond stubble—at first tentatively, as if she wasn’t sure if it was off-limits, and then tenderly, in a gesture far too intimate for a first meeting.

“It’s prickly.” She smiled with curiosity. “And coarse.”

“By this time of night that’s what happens,” I said.

I felt the back of her hand down to the tips of my toes. It didn’t feel like an experienced touch, one of a woman who knew exactly how to hit the right nerves, at the right time of night. In fact, it was quite the opposite. I pegged her as an amateur at the sport of seduction, but it was refreshing.

She finally dropped her hand to her lap, and she left it there, as if not knowing what to do with it next. It was then that I made my first mistake of the night—well, second, if you count missing a party at David Duplaine’s beach house honoring the governor of California. I fleetingly glanced at the wall clock to check if we had time for another set. The girl’s eyes followed mine.

“You have to leave,” she said. “They’ll be back soon. They can’t know you’ve been here.”

“Who will be back? The party’s going to go late.”

“You have to go.”

“Can I see you again?” It sounded like begging. I didn’t know if it was her naïveté, off-kilter beauty, crooked smile or all three, but I was enchanted. “Can I get your name?” I asked, when she didn’t answer the first question.

“I need you to promise me something,” she said. “Promise you’ll forget you ever met me. Please. Because if you remember, it’s likely to get both of us into trouble.”

I didn’t answer because it was a promise I was unwilling to make.

The girl clenched her fist and then uncurled her fingers quickly, as if they were fireworks or a blooming flower. Then she said:

“Poof. See, you’ve forgotten me.”

“We’ve gotta work on your magic tricks,” I said. “You’re still here.”

She smiled despite herself, but then she set her eyes on me seriously.

“I don’t want you to get involved with me, with all of it. No one can ever, ever know you’ve been here. And as lovely as our tennis game was, you may never come back.”

I could tell that by nature she was a fanciful girl, which made the gravitas of her tone even more foreboding. She had presented me with an opening when she peered up at the tree, but now she had closed the door for good.

I nodded, because there was little else to do but leave her as instructed. I climbed to the top of the canopy, hoisted myself up onto the wall and then swung my way into the oak tree.

I watched from the oak as she eliminated all traces of me. She emptied my glass, clumsily washed and dried it, and put it in the kitchenette cabinet. She fluffed the pillow on my leather chair, slid the racket back in cellophane and swept my side of the court in the awkward manner of someone who was learning a skill for the first time.

Once satisfied that she had effectively made me disappear, the girl abandoned the tennis court, leaving the gate to crash back and forth in the wind because she didn’t trouble herself to latch it. She walked up the lawn toward the manor, tightly squeezing her arms around her.

Halfway along the well-lit path to the grand house she turned around and looked up at the oak tree. She extended her right arm as far as it would go and she spread her fingers out in the tree’s general direction, as if she were reaching for something on a high shelf, something so fragile it might break into pieces if she grabbed it.

Seven

I drove out of Bel-Air, crossed Sunset Boulevard and ended up in the parking lot of the mini-mall I had been at just hours earlier renting my tuxedo. It was empty, storefronts dimly lit from the interior with single lightbulbs. That was what was interesting about Los Angeles: its great glory and its gritty underbelly were often walking distance apart. I think the city planners created it that way on purpose. Los Angeles is a recycle bin for dreamers, and the dream needs to be always visible but just slightly out of grasp.

I had stopped there to check my voice mails, of which there were many, and then call Lily, but I lit a cigarette instead of doing either. A street lamp above me flickered a few times with a buzzing sound. It made a go of it, but then went black.

It felt like autumn in Cambridge. Or maybe it felt like Milwaukee. I couldn’t remember anymore, because those cities felt like lifetimes ago. I wondered sometimes if it was the same Thomas Cleary who had lived there or if it was a different man, one I had met in a bar and who had told me his story over a couple of pale ales.

And as for Manhattan, well, that definitely couldn’t have been this lifetime.

I stopped and realized it had been two hours since I had thought of Willa. I hadn’t thought of her once on that tennis court. Relief—or was it sadness?—crept into my heart.

Sure, I had been on dates after Willa, but inevitably, sometime around the appetizer, the comparisons would creep in, and the date would end in a promise never kept.

Willa.

I had lived with an imaginary lover for so long, and it was becoming almost impossible to believe that at this very minute she still existed, in a place so different and far from mine. In the first days without her she was as vivid and clear as a photograph, and I knew where she would be at any moment, or I could have guessed.

In those first weeks without her it was the nights that were the worst. I lay in bed begging for sleep; and if not sleep, the morning, because at least the morning brought the sun. In those black nights I would feel her forgetting me, and somehow that was the worst part.

I began to forget her eventually, too, and it was both my blessing and punishment. After two years her face finally started to blur, and soon after, the fruity smell of her shampoo and the scent of the jasmine behind her ears stopped haunting me. Her eyes became a vacant place, a blackness from which someone had once looked at me lovingly a long time ago. The same went for her arms and her toes, the lips I kissed past midnight, the slender long neck I whispered into in Central Park.

I was lost in thought when my phone rang. The number was private.

“Hello,” I said, tossing the stub of my cigarette to the ground.

Lily skipped salutations. “My goodness, Thomas. We were worried sick about you. You never showed up to the fund-raiser.”

“I went to the wrong house. I went to David’s house in Bel-Air by accident.”

“Kurt did give you the address, didn’t he?” Lily asked. In fact, Kurt hadn’t specified an address. I barely knew Kurt, but I already didn’t much care for him. He always lurked around, like a prison warden searching for an excuse to use his club. And then there was that handshake. Never trust a man whose grip is too sure, my father had always preached.

Could Lily have manipulated events to send me to the wrong house?

I paused before answering. I could lie to Lily and tell her Kurt gave me the address, or betray Kurt and tell Lily he had called me to confirm but hadn’t told me that the party was in Malibu. I was under the early impression lies were passed around this group like hors d’oeuvres at a cocktail party. But I suspected loyalty was deemed a valiant trait.

“He did, but I forget to check my messages and only received it a minute ago. I apologize. It was a stupid oversight. How was the party?”

“I hate political parties—they’re terribly boring. You didn’t miss a thing. Even the filet was tough.” Lily paused then asked offhandedly, “Was anyone at David’s?”

I didn’t answer right away. The girl had made me promise to keep our meeting a surreptitious one. And, besides, it was such an enchanting evening that sharing it would feel like marring its perfection.

“No. There was no one home.”

“What a terrible coincidence,” Lily said, sounding genuinely disappointed. “David has more security than royalty. They must have all been at the governor’s party. This had to have been the only night of the year the house was vacant. Otherwise, someone could have driven you to Malibu or at least pointed you in the right direction.”

“I’m sorry I missed the fund-raiser.”

“I knew it had to be a mix-up, because Midwestern boys are so typically reliable. David said it would be possible to arrange a short interview for you tomorrow with the governor.”

I skipped forward and imagined what Rubenstein would say when I told him I’d landed an interview with the governor. He had been my salvation after my fall from grace, and I still wanted to make him proud.

“Would you like that?” Lily asked, when I didn’t answer.

It was another one of Lily’s rhetorical questions. I accepted and then hung up. I lit another cigarette, and the world seemed to light up, too. The governor. The world of Lily Goldman was full of presents, and I couldn’t help but wonder if there were strings attached to every last one of them.

Eight

The next morning the rain started.

It began with a few stray drops, gentle and unassuming. But by afternoon, as I sat down with the governor in the library of a private club in downtown Los Angeles, the clouds had opened. Water puddles had turned to flash floods and roads across the city were closed.

It rained for the next four days, and the young woman on the tennis court handcuffed my thoughts. When I think back on those days after our first meeting I only recall staring at the rain and thinking of her. Everyday tasks—work, errands and sleep—sparkled somehow, as if her enchanting spell hung over even the most mundane things. She was ubiquitous; no corner of the world could hide her. I thought of her bare shoulders, the way her long ponytail brushed against her dress when she ran for the ball, how her diamond bracelet got caught in her hair each time she put her hand through its blond tendrils. All other food tasted dull compared with the pineapple she had placed on my tongue, and no air tingled my skin like the cool air of that night on the tennis court, and no touch felt as electric as her fingers on my skin.

Had the situation been different—if she was the friend-of-a-friend, a girl I met at a bar—I could have just asked about her. But that was not an option. Asking Lily would have been retracting my previous story, and I got the distinct sense from the girl that she didn’t want anyone to know about our secret tennis game.

So, instead, I tried to learn more about her. The evening had left a bread-crumb trail of clues behind. The food and drink seemed tailored to the girl’s taste, and she had a ball-speed radar device, which wasn’t the sort of thing one would bring along for a visit to someone else’s house. I thought then of the evening of the Blooms’ dinner party, the single upper-floor light that had gone dark when we dropped David off at his estate. I supposed it could have been the staff, but I doubted a housekeeper would be upstairs at that hour. It had to have been her.

While at work, I crawled through David’s life virtually on hands and knees, searching for a pinhead of a clue. I scanned microfiche, birth certificates, city hall records and school attendance lists at all the top private schools, but every search was coming up empty. As I had suspected, David had no children. His romantic life was nonexistent. He hadn’t been photographed beside a lover in years, and there hadn’t been any mention of anyone in the ample press he received.

On nothing more than a whim, I then did the same searching for Lily. I found pictures as far back as her childhood. There was Lily at five years old, flanked by her parents at the premiere of one of her father’s movies. Then Lily winning her science fair with the invention of the lightbulb at John Thomas Dye. Then there was a thirteen-year-old Lily, in jodhpurs and a crisp white shirt, racing a beauty of a Thoroughbred in Hidden Hills at what must have been the Goldmans’ equestrian estate—a stone mansion draped in ivy with shutters.

After eighteen, Lily disappeared from Los Angeles. I had learned in bits and pieces through our dinner-party conversation that Lily had eventually “escaped to the Rhode Island School of Design,” and then she had gone even farther away to work for an editor at Paris Vogue, to “learn French and sleep with the French”—a quote Lily had tossed out over a dessert wine. In her midtwenties Lily made an abrupt U-turn and returned to the city of her birth and good breeding and started her antiques shop as a hobby. Years later she had created a quiet empire of furniture, fabrics and real estate holdings.

I was ready to put my search to rest when I stumbled upon a photo in the Los Angeles Times, which I would have missed if the shuffling microfiche hadn’t decided to stop on that specific page. I enlarged the page tenfold, trading crisp for fuzzy.

The caption read, “Movie mogul Joel Goldman, his daughter, Lily, and friends play tennis at Mr. Goldman’s vacation house.” I looked closer, shocked to discover that one of the friends was none other than a very young Carole Partridge.

The four stood on a clay tennis court. Joel commandeered the photo—as he always seemed to—holding a racket in his left hand, a drink in his right, and wearing a wide victorious grin on his face. Lily seemed to be in her midthirties at the time, and she wore a demure dress and a ponytail and carried a bottle of Orangina. Behind her, almost off camera, was another man of indeterminate age. I tried to focus the microfiche on him, but he turned grainier rather than clearer. What I could tell was this: he was tall, broad and focused on Lily.

Carole was the youngest of the group, and she stood in front. My guess was she was about seventeen compared to Joel’s sixty, and he rested his drink on her shoulder in a protective manner. She donned a barely there white tennis dress and posed with her hand on her hip, as if she were emulating an older, more experienced woman she had seen strike the same pose. She was all legs, and her breasts seemed too big for her, as if they were things that needed to be grown into. Her hair was pinned up in a beehive—an odd hairstyle for tennis—and her charcoal-lined eyes teased the camera.

My gut told me that the photo meant something, something more than the rest of my research combined. I looked at it again, focusing on that mysterious man in the background. Lily had never married—unusual for a woman of her social standing—and judging by the photos and news clippings there hadn’t been a significant other throughout the years. It was possible this guy was a lover. If so, that begged the further question of what had happened.

There was something about the photo that seared through me.

I couldn’t figure it out. I printed the photo, and I pressed it between the pages of my notebook like a rose from a long-lost love. A reminder of something important—something not to be forgotten.

* * *

Ironically, it was in this period of distractedness that my star was finally rising at the Times. I learned quickly that once Los Angeles decides to sprinkle you with its stardust, it shakes so generously you glitter.

I say this because after those first few stories my sky twinkled brightly. There was the story on Joel, followed by the David Duplaine shake-up, the Millstone coverage and then the interview with the governor. I would never know how I had won Phil Rubenstein’s favor after what had happened at the Journal, but what I came to understand was that Los Angeles, above anything else, was a city of forgiveness and second chances.

Scarcely three weeks after my first meeting with Lily Goldman, life moved from slow motion to the speed at which a race-car driver accelerates at the drop of the green flag. The invitations poured in—not to the second-rate parties that had always been my lot, but to first-rate premieres and galas. I attended a few, met new people and was invited to more. Studio publicists lunched me and Rubenstein slipped me the choicest articles.

I was working at the paper early one morning—no later than 7:00 a.m.—when my phone rang from a private number. It was Lily.

I barely had a chance to say hello.

“Thomas, darling, I only have a moment, but I’m calling to insist you join me this evening at Carole’s. She and Charles are having a small dinner, and I haven’t seen you in months.”

This was a slight exaggeration. “I’d love to come,” I said stoically, for I believed that emotion was a badge of weakness in this group. “Please extend a thank-you to Carole. Is there something she’d like me to bring?”

“Absolutely not. The last I heard you are not a member of Carole’s staff,” Lily said. “Kurt will pick you up at six thirty.”

* * *

As promised, Kurt picked me up at six thirty. This time we fetched Lily on our way to our destination, and after Lily’s house we drove a few blocks before reaching a pair of stone columns, each crowned with a vintage gas lamp. A tall wooden gate stared at us, and a personal security car waited beside one of the columns.

Lily waved in the general direction of the security guard in a familiar manner and the gates opened.

We wound our way up a steep driveway that must have been a quarter of a mile long. Once we arrived we were rewarded with an incredible view of Los Angeles. It was a view that shouldn’t have been available for private purchase. Below us, sprinklers watered the fairways of the Bel-Air Country Club with perfectly arched trajectories, and uniformly dressed groundskeepers raked the country club’s sand traps. Beyond, Los Angeles was just beginning to wake up and glitter for the night as the sun was setting over a sliver of ocean that sparkled like a mirror.

I wished I could bottle that view. I looked over to Lily. She seemed indifferent to the blanket of lights that lay before us. She straightened out my new shirt and pants.

“The city feels so small from up here,” I said.

“It’s trickery,” Lily said. “It makes us feel like we’re the powerful ones, even though nothing could be further from the truth.”

I glanced at her incredulously.

“It’s true. We’re all just renters, Thomas. Someday our leases will be up. Carole’s, mine, yours... Look, my father’s just ended. An eighty-one-year lease on life—that was all he got.”

The city buzzed dully in the distance. Lily squinted at an imaginary point, and I wondered what she was thinking about. It was strange; her father had passed away around a month ago, but Lily hadn’t seemed deeply affected by it. I wondered if it was a veneer as fastidiously crafted as her shop and her house.

I turned around to give Lily a moment, and for the first time I noticed the house. The white brick mansion was perched adjacent to the egg-shaped cobblestone motor court. It was a wedding cake of a house—with a second story slightly smaller than the first, and a few curlicue frills for decoration. It was a grander, whiter, more sprawling version of the traditional house surrounded by the picket fence that suburban girls dream of. I imagined it was built in the late 1930s or early ’40s, post-Depression for a manufacturing or real estate tycoon. The mansion appeared purposely situated to get the maximum vistas, but it was plotted in such a way that you might almost miss it when you drove up—the real estate equivalent of Lily Goldman’s false modesty.

There was no need for doorbells at houses like these. Instead, a butler in a black coat and white gloves held the door open for us and led us into the foyer. He greeted Lily by name and Lily introduced me as “Thomas Cleary, the finest reporter in Los Angeles.”

A large antique iron birdcage hung from the entry’s ceiling in lieu of a chandelier. It had a whimsical effect, as if the house’s owners were trying not to take themselves too seriously. A sweeping stairway made for brides or goodbyes crawled up the wall, and sconces cast a soft glow over us.

The butler escorted us toward the stairway, under which a secret door led us into a formal dining room wrapped in hand-painted wallpaper depicting an ancient Asian landscape complete with geishas, canoes, swans, hummingbirds, pergolas and flowers. The Asian chandelier overhead seemed plucked from the wallpaper into real life.

The group was sipping before-dinner cocktails. I decided that there must have been a tribal theme to the evening: Emma wore a feathered headdress, Carole donned heavy silver-and-turquoise jewelry that contrasted with her red-apple lips, and the menus that rested on our plates indicated we were to be served buffalo as our main course.

Charles approached us eagerly. He kissed Lily’s cheek and shook my hand.

“Thomas, thank you so much for joining us. I’ve been reading your bylines. You sure have a knack for the written word.”

“Thank you,” I said, because Charles was the type of man who would say something like that and genuinely mean it. “How’s the screenplay coming?”

“Fantastic, chap.” Charles swept David into conversation with his right arm. “David, you remember Thomas?” He always seemed to veer the subject away from himself, as if he wasn’t worthy of discussion.

“Of course.” David’s expression was even. “We missed you at the governor’s party, but I trust your reason for absence was a good-looking one.”

My stomach dropped. I glanced to my left, to where Lily had just been, but she was no longer there. Instead, she stood alone on the other side of the room, adjusting a painting that had tipped slightly off its proper axis.

The girl had made it clear that no one could find out about our tennis game. I wondered if David had known I was there. The estate was peppered with video security. I had seen the cameras outside when I was waiting at the gate for someone to answer the buzzer, but surprisingly I didn’t see cameras around the tennis court.

Just then, Charles squeezed my arm and presented me with a gimlet stuffed with ice.

“We have a gimlet prepared, just the way you like it.”

I took a deep well-needed sip. Charles and I stood at the doors, looking outside at a carpet of green.

“How are your birds?” I asked. “I heard something about homing pigeons.”

“Yes. Interesting sport, if you can call it that. I picked it up in my youth.” Charles smiled to himself, and there was something sad and longing about it. “We lived in Manhattan during the week and Tuxedo Park on the weekends. The pigeons would follow us between the two.”