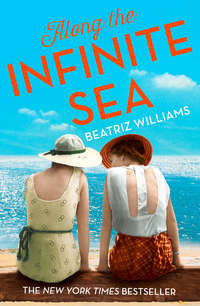

Along the Infinite Sea: Love, friendship and heartbreak, the perfect summer read

“Ah. Now, this is a curious thing, a very interesting thing. Why, Annabelle? Tell me.”

“Surely you know already.”

“I know very well why I am out of sorts. I am desperate to know why you are out of sorts.”

The water slapped against the side of the ship. I counted the glittering waves, the seconds that passed. I pressed my thumbs together and said: “I don’t know. Just restless, I suppose. I’ve been cooped up for so long. I’m used to exercise.”

He leaned his elbow on the railing, a foot or so from mine. I felt his breath as he spoke. “You are bored.”

“Not bored.”

“Yes, you are. Admit it. You have had nothing to do except fetch and carry for a grumpy patient who does not even thank you as you deserve.”

I laughed. “Yes, that’s it exactly.”

“There is an easy cure for your boredom. Do something unexpected.”

“Such as?”

“Anything. You must have some special talent, besides nursing. Show it to me.” He transferred his cigarette to his other hand and reached into his pocket. “Do you draw? I have a pen.”

“I don’t have any paper.”

“Draw on the deck, if you like.”

“I’m not going to ruin your deck. Anyway, I’m hopeless at drawing.”

“A poem, then. Write me a poem.”

I was laughing, “I don’t write, either. I play the cello, quite well actually, but my cello is back at the Villa Vanilla.”

“The Villa Vanilla?”

“My father’s house.”

Stefan began to laugh, too, a handsome and hearty laugh that shivered his chest beneath his dinner jacket. “Annabelle. Am I just supposed to let you slip away?”

“Yes, you are.” His hand, broad and familiar, had worked close to mine on the railing, until our fingers were almost touching. I drew my arm to my side and said, “I do have one talent.”

“Then do it. Show me, Annabelle.”

I reached for the sash of my dressing gown. Stefan’s astonished eyes slid downward.

The bow untied easily. I let the gown slip from my shoulders and bent down to grasp the hem of my nightgown.

“Annabelle—”

I knotted the nightgown between my legs and turned to brace my hands on the railing. “Watch,” I said, and I hoisted myself upward to balance the balls of my feet on the slim metal rod while the moonlight washed my skin.

“My God,” Stefan said, reaching for my legs, but I was already launching myself into the free air, tucking myself into a single perfect roll, uncurling myself just in time to slice into the water beneath a silent splash.

9.

“You are quite right,” called Stefan, when my head bobbed at last above the surface. “That is an immense talent.”

“I was club champion four years running.” The water slid against my limbs, sleek and delicious.

He pointed to the side of the ship. “The ladder is over there, Mademoiselle.”

“So it is.”

But I didn’t swim toward the ladder. I turned around and kicked my strong legs and stroked my strong arms, toward the shore of the Île Sainte-Marguerite, waiting quietly in the moonlight.

10.

I lay in the rough sand without moving, soaking up the faint warmth of yesterday’s sun into my bones. I thought I had never felt so magnificent, so utterly exhausted and filled with the intense pleasurable relief that follows exhaustion. The water dried slowly on my legs and arms; my nightgown stiffened against my back. I inhaled the green briny scent of the beach, the trace of metal, the hint of eucalyptus from the island forest, and I thought, Someone should bottle this, it’s too good to be true.

I didn’t count the passing of minutes. I had no idea how much time had passed before I heard the rhythmic splash of oars in the water behind me.

“There you are, Mademoiselle,” said Stefan. “I had some trouble to find you in the darkness.”

I sat up. “You haven’t rowed all the way over here!”

“Of course. What else am I to do, when Annabelle dives off my ship and swims away into the night?”

I rose to my unsteady feet and took the rope from his hand. “Let me do that.”

“I assure you, I can manage.”

“If your wound opens—”

“Don’t be stupid.” He pulled on the rope and the boat slid up the sand. I took a few steps away and sat down again. My legs were still a little wobbly, my skin still cool after the long submersion in the sea. Stefan reached into the boat and drew out the silver bucket and a pair of glasses.

“You’ve brought champagne?”

“What’s this? Did you think I would forget the refreshment?” He sank into the gravelly sand next to me and braced the bottle between his hands. His thumbs worked expertly at the cork until it slid out with a whisper of a pop.

“You are quite mad.”

“No, only a little. A little mad, especially when I saw Annabelle’s body lying there like a ghost in the moonlight, without moving.” He handed me a foaming glass. “And then I thought, No, my Annabelle would never swim so far through the water and then give up when she had reached the shore. But here.” He set down his own glass in the sand and shrugged his dinner jacket from his arms. “You must take this.”

“I’m not that cold, really. Nearly dry.”

“And how would I answer to God if Annabelle caught a chill while I still wore my jacket?” He placed it over my shoulders, picked up his glass, and clinked it against mine. “Now drink. Champagne should always be drunk ice-cold on a beach at dawn.”

“Is it dawn already?”

“We are close enough.”

I bent my head and sipped the champagne, and it was perfect, just as Stefan said, falling like snow into my belly. Next to me, Stefan tilted back his head and drank thirstily, and the beach was so still and flawless that I thought I could feel his throat move, his eyelids close in bliss.

“That woman,” I said. “The blond woman, the one who came to visit you. Is she your mistress?”

“Yes,” he said simply, readily, as if there couldn’t possibly exist any prevarication between us.

“She’s very beautiful.”

“That is the way of it, I’m afraid. Only the rich deserve the fair.”

I laughed. “I thought it was the brave. Only the brave deserve the fair.”

“A silly romantic notion. When have you ever seen a beautiful woman with a poor man? An ugly man perhaps, or a timid one, or a stupid one, or even an unpleasant one. But never a poor one.”

“Do you love her?”

“Only so much as is absolutely necessary.”

I swallowed the rest of my champagne and set the glass in the sand between us. My vision swam. “I don’t quite know what you mean.”

“No,” he said. “Of course you don’t.”

He lay back in the sand, and after a moment I lay back, too, a few inches away, listening to the sound of his breath. The beach was coarse, not like the sand on my father’s beach; the little rocks poked into my back. Stefan’s jacket brushed my jaw, enclosing me in an intimate atmosphere of tobacco and shaving soap. The moon had slipped below the horizon, and we were lit only by the stars, just as we had been on the first night as we rushed through the water toward the safety of Stefan’s yacht. I had known almost nothing about him then, and ten days later, having lived next to him, having spent hours at his side, having talked at endless length about an endless variety of subjects, I didn’t know much more.

“I love your library,” I said. “You have so many lovely books.”

“Yes, it is the family library, collected over many generations.”

“Your family library? Don’t you think that’s risky? Keeping it all on a ship?”

“No more risky than keeping it in our house in Germany, in times like this. When a Jew is no longer even really a citizen.”

I lifted my head. “You’re a Jew?”

“Yes. You didn’t know that?”

“I never thought about it.” I laid my head back down and studied the stars. Stefan’s fingers brushed my hand, and I brushed them back, and a complex and breathless moment later we were holding hands, studying the stars together.

“Tell me, Annabelle,” he said. “Why have you never asked me how I came to be shot in the leg, one fine summer night on the peaceful coast of France?”

“I thought you’d tell me when you trusted me. I didn’t want to ask and have you tell me it was none of my business.”

“Of course it is your business. I will tell you now. The men who shot me, they were agents of the Gestapo. You know what this is?”

“Yes, I think so. A sort of secret police, isn’t it? The Nazi police.”

“Yes. They rather resent me, you see, because instead of waiting quietly for the next law to be passed, the next column to be kicked out from under me, I am seeking to defend the country that I love, the real Germany, the one for which my father lost his eye and his jaw twenty years ago.”

“I see.”

“I will not bore you with the details of what I was doing that night. But you are in no danger from the French authorities. I want you to know that, that I have not made you some sort of fugitive. But it was necessary, you see, that the man who shot me didn’t know what became of me, or who had helped me to safety.”

“My brother.”

“Yes, de Créouville and his friends. And you.” He lifted my hand and brought it to his lips, which were warm and soft and damp with champagne.

My heart was jumping from my chest. I felt my ribs strain, trying to contain it. I opened my mouth to say something, and my tongue was so dry I could hardly shape the words.

“I’m glad,” I said, “I am proud of my brother, that he was helping you.”

“Yes, he is a good man.”

“I suppose”—I swallowed—“I suppose you’ll go on doing these things, whatever they are. You will go on putting yourself in this danger.”

He didn’t speak. We lay there in darkness, shoulders touching, hips touching, hand wound around hand. I might have drifted to sleep for a moment, because I opened my eyes to find that the stars had disappeared, and the sky had turned a shade of violet so deep it was almost charcoal. Next to me, Stefan lay so still I thought he must be asleep. I didn’t move. I was afraid to wake him.

I thought, I will remember this always, the smell of him, cigarettes and champagne and salt warmth; the strength of his hand around mine, the rhythm of his breath, the rough texture of sand beneath my head.

“It’s almost dawn,” he said softly.

“I thought you were asleep.”

“I was.”

The water slapped against the sand. A perimeter of color grew around the horizon, and Stefan sat up, still holding my hand. “The sun will be up soon,” he said. “We can’t see it yet, because of the cliffs to the east. In Venice, it is fully light.”

“I haven’t been to Venice.”

“It is beautiful, a kind of dreamy beauty, like a painting of someone’s memory. Except it smells like the devil, sometimes.” He nodded at the faint violet outline of the Fort Royal, just visible above the trees. “I have been staring at that building through my porthole, every day. Thinking about the men who were imprisoned there.”

“Yes, I noticed that book, when I brought it from the library. The Dumas, the one about the Man in the Iron Mask.”

“Except it wasn’t really an iron mask. It was velvet black, according to those who saw him. Voltaire was the one who turned it into iron, for dramatic purposes, or so one supposes.”

“Have you ever been inside?”

“No.” He paused and smiled. “Would you like to go now?”

“What, now? But it isn’t open yet.”

“Even better. We will have the place to ourselves.” He swung to his feet, a little awkwardly, and pulled me up with him. “A good thing, since you are only wearing a nightgown and my dinner jacket.”

“What about your leg?” I said breathlessly.

He shrugged. “Don’t worry about my leg anymore, Nurse. You are off duty, remember?”

11.

We walked slowly, because of my bare feet and Stefan’s leg, and because the world around us seemed so sacred and primeval, like Eden, filling with pale new light, fragrant with pine and eucalyptus. There was a long straight allée leading directly to the fort, and we saw nobody else the entire way. “There are fisherman in the village,” Stefan said. “They are probably setting out in their boats. And there will be a lot of tourists later in the morning and the afternoon.”

“I’d rather wake up early and spend time with the fishermen. I’d rather see the place as it really is, as it used to be lived.”

“Yes, the tourists are a nuisance. Have you been to Pompeii?”

“No. I’ve never been to Italy at all.”

“We must go there someday. You would like it very much. It is as if you have walked into an ordinary old village, except you begin to walk down the street and you see how ancient it is. There are shards of old pottery littering the ground. You can pick one up and take it with you.”

“Don’t they mind?”

“They only really care about the frescoes. The frescoes are astonishing, though they are not for the faint of heart.”

“Are they violent?” I asked, thinking of the gladiators and the casual Roman lust for blood.

“No, they are profoundly erotic.”

A bird sang at us from within a tree somewhere, a melancholy whistle. The low crunch of our footsteps echoed from the woods.

“There are also casts,” Stefan said. “They found these hollows in the ash, the hardened ash, and so they had the good idea to pour plaster of Paris into these hollows, and when it dried and they chipped away the molds, there remained these exact perfect casts of the people who had died, who had been buried alive in the ash. You can see the terror in their faces. And that, my Annabelle, is when you realize that this thing was real, that it actually happened, this unthinkable thing. Each cast was a living person, two thousand years ago. These casts, they are proof. They are photographs of a precise moment, the moment of expiration. They are like the resurrection of the dead.”

“How awful.”

“It’s awful and beautiful at once. The worst was the dog, however. I could bear the sight of the people, but the dog made me weep.”

“You don’t mind the people dying, but you mind the animals?”

“Because the people knew what was happening to them. They knew Vesuvius was erupting, that the town was doomed. They couldn’t escape, but at least they knew. The dog, he had no idea. He must have thought he was being punished.”

“The people thought they were being punished, too. That the gods were punishing them.”

“Yes, but we humans are all full of sin, aren’t we? We know our mortal failings. We know our own culpability. This poor dog never knew what he had done wrong. Here we are.”

A wall appeared to our right, behind the trees. I looked up, and the dawn had broken free at last, gilding the peaks of the fort, which had somehow, in the course of our conversation, grown into a forbidding size and complexity. Ahead, the trees cleared to reveal a paved terrace.

“Can we go in?” I asked.

“We can try.”

The sun had not quite scaled the rooftops yet, and the terrace was in full shade. We walked up the path until an entrance came into view, interrupting the rough stone of the fort walls: a wide archway beneath a modest turret. There was no door, no impediment of any kind. A patch of white sun beckoned on the other side.

“Are there any soldiers about, do you think?”

“No, the garrison was disbanded some years ago, I believe. It is now a—I don’t know if there is some particular term in English—a monument historique. I suppose it belongs to the people of France.”

“Then it’s mine, because I am a person of France, after all,” I said, and I walked under the archway and up the stairs to the patch of light that squeezed between the corners of two buildings.

“But you are not simply a person of France, are you?” said Stefan, coming up behind me. “You are a princess of France.”

“That doesn’t mean anything anymore. We’re a republic. We shouldn’t even have titles at all. Anyway, I’m half American. It’s impossible to be a princess and speak like a Yankee.”

“It suits you, however. Especially now, when the sun is touching your hair.”

I stopped walking and turned to Stefan, who stopped, too, and returned my gaze. He was almost a foot taller than I was, and the sun had already found his hair and eyes and most of his face, and while he could sometimes look almost plain, because his bones were arranged so simply, in the full light of morning sunshine he was beautiful.

“Don’t look at me like that,” he said.

“Like what?”

“Like you want me to kiss you.”

“But I do want you to kiss me.”

Stefan shook his head. “How can you be like this? No one in the world is like you.”

“I was going to say the same about you.”

He lifted his hand and touched the ends of my hair, and such was the extraordinary sensitivity of my nerves that I felt the stir of each individual root. “I don’t know how I am going to bear this, Annabelle,” he whispered. “How am I going to survive any more?”

I didn’t say anything. I didn’t want to disturb the delicate balance, one way or another. I took a step back, so I was standing against the barracks wall, which was already warm with sunshine, and Stefan followed me and raised his other hand to burrow into my hair, around the curve of my skull. His gaze dropped to my lips.

“Alles ist seinen Preis wert,” he said, and he lowered his face and kissed me.

I held myself still as his lips touched mine, lightly at first and then deeper, until he had opened me gently to taste the skin of my mouth. I didn’t know you could do that, I didn’t know you could kiss on the inside. I thought it was all on the surface. He tasted like he smelled, of champagne and cigarettes, only richer and wetter, alive, and I lifted my hands, which had been pressed against the barracks wall, and curled them around his waist, because I might never have the chance to do that again, to hold Stefan’s warm waist under my palms while his mouth caressed mine. He cradled the back of my head with one hand and the side of my face with the other, and he ended the kiss in a series of nibbles that trailed off somewhere on my cheekbone, and pressed his forehead against mine. I relaxed against the barracks wall and took his weight. A bird chattered from the ridgepole.

“All right,” he said. “Okay. Still alive.”

“I’m sorry. I don’t really know how to kiss.”

“Don’t ever learn.”

I laughed softly and held him close against my thin nightgown. The new sun burned the side of my face. I said, “I suppose your mistress wouldn’t be happy to see us now.”

Stefan lifted his head from mine. “As it happens, I do not give a damn what this woman thinks at the moment, and neither should you. But come. The groundskeepers will be coming soon, and then the tourists. It will be a great scandal if we are seen.”

“I don’t care.”

“But I do. I will not have Annabelle de Créouville caught here in her nightgown with her lover, for all the world to stare.” He gave my hair a final stroke and picked up my hand. “Can you walk all the way back in your bare feet, do you think?”

“Must we? I wanted to see the rest of the fort.”

“We will come back someday, if you like.”

His voice was warm in my chest. I wanted him to kiss me again, but instead I followed him around the corner of the barracks to the stairs. Your poor feet, he said, looking down, and I said, Your poor leg, and he kissed my hand and said, The lame leading the lame.

I said, I thought it was the blind, the blind leading the lame, and he said, I am not blind at all. Are you?

No, I told him. Not blind at all.

There were two weather-faced men smoking on the terrace when we passed under the arch. They looked up at us and nearly dropped their cigarettes.

“Bonjour, mes amis,” said Stefan cheerfully, and he bent down and lifted me into his arms and carried me the rest of the way, to hell with the wounded leg.

12.

An hour later, we were standing inside the Isolde’s tender, a sleek little boat with a racehorse engine, motoring across the sea to my father’s villa on the other side of the Cap d’Antibes. The wind whipped Stefan’s hair as he sat at the wheel, and the sun lit his skin. Against the side of the boat, the waves beat a forward rhythm, and the breeze came thick and briny.

We hardly spoke. How could you speak, after a morning like that? And yet it was only seven o’clock. The whole day still lay ahead. We rounded the point, and the Villa Vanilla came into view, white against the morning glare. Stefan brought us in expertly to the boathouse, closing the throttle so we wouldn’t make too much noise.

“I will walk you up the cliff,” he said. “I do not trust that path.”

“But I’ve climbed it hundreds of times. I walked down it in the dark, the night we met.”

“This I do not wish to think about.”

The house was silent when we reached the top. No one would be up for hours. There was a single guilty champagne bottle sitting on the garden wall, overlooked by the servants. Stefan picked it up as we passed and then looked over at the driveway, which was just visible from the side as we approached the terrace. “My God,” he said, stopping in his tracks. “Whose car is that?”

I followed his gaze and saw Herr von Kleist’s swooping black Mercedes, oily-fast in the sun. “Oh, that’s the general, Baron von Kleist. I’m surprised he’s still here. He didn’t seem to be enjoying himself.”

“Von Kleist,” he said.

“Do you know him?”

“A little.”

We resumed walking, and when we had climbed the steps and stood by the terrace door Stefan handed me the empty champagne bottle and the small brown valise that contained my few clothes. “You see? You may tell your brother I have returned you properly dressed, with your virtue intact. I believe I deserve a knighthood, at least. The Chevalier Silverman.”

“What about me? I was the one who nursed you back to health, from the brink of death.”

“But you are already a princess, Mademoiselle. What further honor can be given to you?”

All at once, I was out of words. I was empty of the ability to flirt with him. I parted my lips dumbly and stood there, next to the door, staring at Stefan’s chin.

His voice fell to a very low pitch, discernible only by dogs and lovers. “Listen to me, Annabelle. I will tell you something, the absolute truth. I have never in my life felt such terror as I did when I saw you lying on that beach this morning in your white nightgown, surrounded by the rocks and that damned treacherous Pointe du Dragon.”

“Don’t be stupid,” I whispered.

“I am stupid. I am stupid for you. I am filled with folly. But stop. I see I am alarming you. I will go back to my ship now. It is best for us both, don’t you think?” He kissed my hand. I hadn’t even realized he was holding it. He kissed it again and turned away.

“Wait, Stefan,” I said, but he was already hurrying down the stones of the terrace, and the sound of his footsteps was so faint, I didn’t even notice when it faded into the morning silence.

13.

I passed through the dining room on the way to the stairs, and instead of finding it empty, I saw Herr von Kleist sitting quietly in a chair, eating his breakfast. He looked up at me without the slightest sign of surprise.

“Good morning, Mademoiselle de Créouville,” he said, pushing back his chair and unfolding his body to an enormous height.