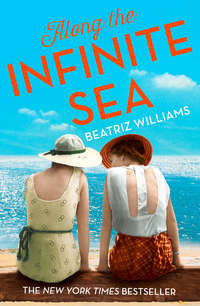

Along the Infinite Sea: Love, friendship and heartbreak, the perfect summer read

“Good morning, Herr von Kleist.” I was blushing furiously. The champagne bottle hung scandalously from one hand, the valise from the other. “I didn’t expect anyone up so early.”

“I am always up at this hour. May I call for some breakfast for you?”

“No, thank you. I think I’ll take a tray in my room.”

“We have missed you these past ten days.”

“I’ve been staying with a friend.”

“So I was told.” He remained standing politely, holding his napkin in one hand, a man of the old manners. The kitchen maid walked in, heavy-eyed, holding a coffeepot, and stopped at the sight of me.

“Bonjour, Marie-Louise,” I said.

“Bonjour, Mademoiselle,” she whispered.

I looked back at Herr von Kleist, whose eyes were exceptionally blue in the light that flooded from the eastern windows, whose hair glinted gold like a nimbus. He was gazing at me without expression, although I had the impression of great grief hanging from his shoulders. I shifted my feet.

“Please return to your breakfast,” I said, and I walked across the corner of the dining room and broke into a run, racing up the stairs to my room, hoping I would reach my window in time to see the Isolde’s tender cross the sea before me.

But it did not.

PEPPER

A1A • 1966

1.

Annabelle waits for her to finish, like a woman who’s done this before: waited patiently for someone else to finish vomiting. When Pepper lifts her head, she hands her a crisp white handkerchief, glowing in the moon.

“Thank you,” says Pepper.

“All better? Can we move on?”

“Yes.”

The engine launches them back down the road. Pepper leans her head back and allows the draft to cool her face. Annabelle bends forward and switches on the radio. “That was too late for morning sickness,” she observes.

“I don’t get morning sickness.”

“Lucky duck. Nerves, then?”

“I don’t get nerves, either.” She pauses. “Not without reason.”

The static resolves into music. The Beatles. “Yesterday.” So far away. Annabelle pauses, hand on the dial, and then lets it be. She sits back against the leather and says, “Are you saying the bastard’s been threatening you?”

“He’s been trying to find me, and I’ve been making myself scarce, that’s all.”

“Why? He is the father, after all.”

“Because I know what he wants.” Pepper examines her fingernails. She thinks, You’re an idiot, Pepper Schuyler, you’re going to spill it, aren’t you? You’re just going to lose it right here. Her throat still burns. She says, “I didn’t even tell him. He found out, I don’t know how. He called me up at the hotel and yelled at me. Why couldn’t I get it taken care of, he wanted to know.”

“What a gentleman.”

Pepper gives up on her fingernails and looks out the side. They’re passing close to the ocean right now, that grand old Atlantic, toiling away faithfully under the moon. “He was very good at the chase, I’ll say that. I always swore I’d never sleep with a married man. I know what everyone says about me, lock up your husbands, but the truth is I just flirt. Like a sport, like some women play bridge. And silly me, I thought he knew that. I thought we weren’t taking it past first base, until we did, one night. Big victory, big glasses of champagne, big beautiful hotel suite, and before you know it, the all-star hits himself a home run right out of the park, a grand goddamned salami. Oopsy-daisy, as my sister Vivian would say.”

Annabelle drives silently. She keeps one hand on the wheel and one elbow propped on the doorframe beside her. Pepper steals a glance. Her head is tilted slightly to one side, showing off her long neck. The skin is still taut, still iridescent in the moonlight. What bargain did she make with the devil for skin like that? Whatever it is, Pepper would happily take that bargain. What was the point of an eternal soul, anyway? It just meant you spent eternity in fleecy boredom, strumming your harp. Pepper would rather have twenty good years on earth, flaunting her iridescent skin, and then oblivion.

“What are you thinking?” asks Pepper.

Annabelle raises her head and laughs, making the car swerve slightly. “Do you really want to know?”

“It beats the Beatles.”

“I was thinking about when I fell in love, actually. How grateful I am for that. We were in the South of France, in the middle of August, and I was nineteen and just crazy about him. We were right by the sea. I thought I was in heaven.”

“What was his name?”

She pauses. “Stefan.”

The radio plays between them, the instrumentals, a low and mournful string. Someone believes in yesterday. Pepper stares at her thumbs in her lap and thinks about the night she lost her virginity. There was no sunshine, no Mediterranean, no mysterious Stefan. There was a friend of her mother’s, after a party. She had flirted with him, because flirting gave you such a rush of delicious power. Such confidence in this newfound seventeen-year-old beauty of yours, that a man twenty years older hung on your every banal word, your every swooping eyelash. That he would tell you how you’d grown, how you were the most beautiful girl he’d ever seen. That he would lead you dangerously into a shady corner of the terrace, overlooking Central Park, and feed you a forbidden martini or two and kiss you—you’d been kissed before, you could handle this—and then do something to your dress and your underpants, and a few blurry moments later you weren’t handling this at all, you were bang smack on your back on the lounge chair with no way to get up, and maybe it was a good thing he’d fed you those martinis, maybe it was a good thing you couldn’t remember exactly how it happened.

The song changes, some new band that Pepper doesn’t recognize. She reaches forward and shuts off the radio.

2.

They reach Cocoa Beach at half past one o’clock in the morning. A bank of clouds has rolled in, obscuring the moon, and Pepper can’t see a thing beyond the headlights. She’s too tired to care, anyway.

“Here we are,” Annabelle says cheerfully. “The housekeeper is in bed, but the cottage should be ready.”

“You do this kind of thing often?”

“No. I just had a hunch I’d have company.”

Pepper stumbles out of the car and follows Annabelle across a driveway and up a pair of stone steps. A little house by the beach, she said, but this is more like a villa, plain and rough-walled, like something you might find in Spain or Italy, somewhere old and hot. The smell of eucalyptus hangs in the air.

Annabelle holds open the door. “I expect you’re tired. I couldn’t keep my eyes open when I was pregnant. I’ll save the tour for tomorrow and take you straight to bed.”

“I’ve heard that one before.”

Annabelle laughs. “I expect you have, you naughty girl.”

Pepper is just awake enough to appreciate the lack of censure in Annabelle’s voice. Well, she is European, isn’t she? She has that welcome dollop of joie-de-whatever, that je ne sais no evil. She’s not one to judge. Maybe that’s why Pepper spilled her guts back there, in the middle of the road, like a cadaver under dissection. Or maybe it was the moon, or the goddamned ocean, or the baby and the hormones and the nicotine starvation. Whatever it was, Pepper hopes to God she won’t regret all this over breakfast.

“We bought the place in 1941,” Annabelle was saying, as they passed through the darkened rooms. “It was built in the twenties, during the big land rush. We got it for a song. It was in total disrepair, not even properly finished, but the bones were good, and there was plenty of room for the children, and it was all by itself, no nosy neighbors. There was something rather authentic about it, which is a difficult thing to find in Florida.”

“I’ll say.”

“I mean, except me, of course!” Annabelle’s midnight exuberance is almost certifiable. Pepper wants to throttle her. Of course, six months ago, Pepper could midnight with the best of them. Six months ago, midnight was just the beginning. That was how she got into this mess, wasn’t it? Too much goddamned midnight, and now here she was, stumbling through an old house in the middle of Florida, knocked up and knocked out.

A latch clicks, a door swooshes open, and now they’re in a courtyard, full of fresh air and lemon trees. Annabelle turns to the wall and switches on a light. Pepper squints.

“Just over here, honey,” says Annabelle.

Pepper follows. “I don’t mean to be pushy, but does this guest cottage of yours happen to have a working lavatory?”

Annabelle claps a hand to her cheek. “Oh, my goodness! What an idiot I am! It’s been so long since I had babies. Come along. My dear, you should have said something. I didn’t realize you were so polite.”

“I’m not, I assure you. I just didn’t happen to spot any flowerpots along the way.”

The grass is short and damp. They’ve moved beyond the circle of light from the house. Pepper sees a rectangular shadow ahead and hopes to God it’s the cottage, and nobody’s waiting inside. Peace and quiet, that’s all she needs. Peace and quiet and a toilet.

A step ahead, Annabelle opens the door and steps aside for Pepper to enter first. The smell of soap and fresh linen rushes around her.

“Home sweet home. The bathroom’s on the right.”

3.

When Pepper emerges from the bathroom ten minutes later, Annabelle is standing by the window, looking into the night. From the side, her face looks a little more fragile than Pepper remembers, and she thinks that maybe Annabelle is right, that she isn’t really beautiful. The nose is too long. The chin too sharp. The head itself is out of proportion, too large on her skinny long neck, like a Tootsie Pop.

Then she turns, and Pepper forgets her faults.

“All set?”

“Yes. Thanks for the nightgown and toothpaste. I’m beginning to think you had this all planned out.”

“Maybe I did.” Annabelle smiles. “Does that make you nervous?”

Pepper yawns. “Nothing’s going to make me nervous right now.”

“All right. Sleep in as long as you like. I’ll have coffee and breakfast waiting in the main house, whenever you’re up. Is there anything you need?”

“No, thanks.” Pepper hesitates. Gratitude isn’t her natural attitude, but then you didn’t spend your life dangling elegantly from the pages of the Social Register without learning how to keep your legs crossed and your hostess well buttered. “Thanks awfully for your hospitality,” she adds, all Fifth Avenue drawl, emphasis on the awful.

“Oh, not at all. I’m happy I could help.”

Pepper’s radar ears detect a note of wistfulness. She sinks on the bed, bracing her arms on either side of her heavy belly, and says, “Helped me? Kidnapped is more like it.”

“Miss Pepper Schuyler,” Annabelle says, shaking her head, “why on this great good earth are you so suspicious? What have they done to you?”

“A better question, Mrs. Annabelle Dommerich, is why you care.”

An exasperated line appears between Annabelle’s eyebrows. She marches to the bed, drops down next to Pepper, and snatches her hand. Her hand! As if Annabelle is the mother bear and Pepper is Goldilocks or something. “Now, look here,” she actually says, just like a mother bear, “you are safe here, do you hear me? Nobody’s going to call you or make demands on you or—God knows, whatever it is you’re afraid of.”

“I’m not afraid—”

“You’re just going to sit here and grow your baby and think about what you want to do with yourself, is that clear? You’re going to relax, for God’s sake.”

“Hide, you mean.”

“Yes, hide. If that’s what you want to call it. There’s a doctor in town, if you need to keep up with any appointments. The housekeeper can drive you. You can telephone your parents and your sisters. You can telephone that horse’s ass who put you in this condition, and tell him he can go to the devil.”

Pepper cracks out a whiplash of laughter. “Go to the devil! That’s a good one. I can just picture him, hanging up the phone and trotting off obediently into the fire and brimstone, just because Pepper Schuyler told him to. Do you have any idea who his friends are? Do you have any idea who owes him a favor or two?”

“He’s no match for you. Trust me. You hold the cards, darling. You hold the ace. Don’t let those bastards convince you otherwise.”

Pepper stares at the mama-bear hand covering her own. The nails are short and well trimmed, the skin smooth and ribbed gently with veins the color of the ocean. Annabelle doesn’t use lacquer.

“You still haven’t answered my question,” Pepper says. “Why do you care?”

Annabelle sighs and heads for the door. She pauses with her hand right there on the knob. Dramatic effect. Who knew she had it in her?

“All right, Pepper. Why do I care? I care because I stood in your shoes twenty-nine years ago, and God knows I could have used a little decent advice. Someone to keep me from making so many goddamned mistakes.”

ANNABELLE

Antibes • 1935

1.

A week passed. Charles had left with his friends before I returned; I was now wise enough to suspect why. Herr von Kleist packed up his few trunks and roared away in his beautiful Mercedes Roadster later that afternoon. My father—as always—rose late, retired late, and reserved nearly all of his time for his remaining guests. I had little to do except wander the garden and the beaches, to practice my cello for hours, to walk sometimes into the village, to examine the contents of my memory for signposts to my future.

On the seventh day of my isolation, I woke up under the settled conviction that I would move to Paris, to Montparnasse, and teach the cello while I found a master under whom to study. It seemed a natural place for me. I was both French and American, and I had read about how the streets and cafés around the boulevard du Montparnasse rattled with Americans seeking art and life and meaning and cheap accommodation. If a certain handsome young German Jew were then to turn up on my stoop one day, perhaps requiring immediate medical assistance, why, I would take him in with cheerful surprise. I would find a way to weave him into the hectic fabric of my happiness.

I was not going to wait any longer for my life to start. I was going to start my life on my own.

I repeated this to myself—a very nice tidy maxim, suitable for cross-stitch into a tapestry, a decorative pillow perhaps—as I walked down the stairs on my way to the breakfast room, where I expected the usual hours of peace until the rest of the household woke up. Instead, it was chaos. The hall was full of expensive leather trunks and portmanteaus, the rugs were being rolled up, the servants were running about as if an army were on the march. In the middle of it all stood my father, dressed immaculately in a pale linen suit, speaking on the telephone in rapid French, the cord wound around him and stretched to its limit.

“Papa?” I said. “What’s going on?”

He held up one finger, said a few more urgent words, and set the receiver in its cradle with an exhausted sigh. He closed his eyes, collecting his thoughts, and then stepped to the hall table and set down the telephone. “Mignonne,” he said in French, opening his arms, “it is eight o’clock already. You are not ready?”

I took his hands and kissed his cheeks. He smelled of oranges, the particular scent of his shaving soap, which he purchased exclusively from a tiny apothecary in the Troisième, on the rue Charles-François-Dupuis. “Ready for what, Papa?”

“You did not see my message last night?” His eyes were heavy and bruised.

“What message? Papa, what’s wrong?”

“I slipped it under your door. Perhaps you were already asleep.” He released my hands and pulled out a cigarette case from his jacket pocket. His fingers fumbled with the clasp. “It is a bit of a change of plans. We are leaving this morning, returning to Paris.”

“But we were to stay another week!”

“I’m afraid there is some business to which I must attend.” He managed to fit a cigarette between his lips. I took the slim gold lighter from his fingers and lit the end for him. I concentrated on the movements of my fingers, this ordinary activity, to keep the panic from rising in my chest.

“But what about our guests?” I said.

“I have left messages. They will understand, don’t you think?” He pulled the cigarette away and kissed my cheek. “Now run upstairs, ma chérie, and pack your things. Come, now. It is for the best. One should always leave the party before the bitter end, isn’t it so?”

“Yes,” I said numbly, “of course,” and I turned and ran up the steps, two at a time, and burst without breath into my room, where I stayed only long enough to snatch the pair of slim black binoculars from my desk and bolt down the hall in the opposite direction, to the back stairs.

It was now the third week of August, and the sea washed restlessly against the rocks and beaches below as I stumbled along the clifftops, sucking air into my stricken lungs. I inhaled the warm scent of the dying summer, the weeks that would not return. I thought, I don’t care, I don’t care if we leave now and return to Paris, I have my own plans, I will live in Montparnasse, I will be sophisticated and insouciant, and he can find me or not find me, he can love me or not love me, I don’t care, I don’t care.

I skidded to a stop at the familiar rock, the rock where I had sat every day and watched the traffic in the giant mammary curves of the bay, in the delicate cleavage of which perched the village of Cannes. From here, you could see the boats zagging lazily, the ferries looping back and forth to the îsles Lérins, to Sainte-Marguerite, where the fort nestled into the cliffs. I climbed to the top of the boulder and lifted the binoculars to my eyes and thought, I don’t care, I don’t care, please God, please God, I don’t care.

From this angle, to the east of the islands, it was impossible to see where the Isolde lay moored—if she still lay moored at all—behind the Pointe du Dragon. I had tried—no, I hadn’t tried, of course not, I had only dragged my gaze about as a matter of idle curiosity, but there was no glimpse of the beautiful black-and-white ship, longer and sleeker than all the others moored there in the gentle channel between the two islands. I had taken her continued presence there as an article of faith. I had watched the boats ply the water, the stylish motorboats and the ferries and the serviceable tenders, and refused to think about the honey-haired woman who had come to see Stefan that first morning, and whether she was making another trip. Whether an unglamorous nineteen-year-old virgin was easily forgotten in the face of those kohl-lined eyes, that slender and practiced figure.

My legs wobbled, and the vision through the binoculars skidded crazily about. I planted my feet more firmly, each one in a separate hollow, and set my shoulders. The sea steadied before me, blue and ancient under the cloudless sky, and as I stared to the southeast, counting the tiny white waves, as if in obedience to a miraculous summons, I saw a long yacht come into view, around the edge of the point, black on the bottom and gleaming white in a rim about the top of the hull, steaming eastward toward Nice or Monaco, perhaps, or even farther south toward Italy.

The Cinque Ports were supposed to be beautiful at this time of year, and Portofino.

My heart grew and grew, splitting my chest apart, lodging somewhere in my throat so I couldn’t breathe.

“She is a beautiful ship, don’t you think?” said a voice behind me.

I closed my eyes and allowed my arms to fall, with the binoculars, onto my thighs. I thought, I must breathe now, and I forced my throat to open. “Yes, very beautiful.”

“But you know, ships are so transient and so sterile. Nothing grows in them. So I have been thinking to myself, I must really find myself a villa of some kind, somewhere in the sunshine where I can raise olives and wine and children, with the assistance of perhaps a housekeeper to keep things tidy and make a nice hot breakfast in the morning, and a gardener to tend the flowers.”

My chest was moving in little spasms now, taking in shallow bursts of air. I said, or rather sobbed, “And what—will you do—in the winter?”

“Ah, a good question. Perhaps an apartment in Paris? One can follow the sun, of course, but I have always thought that it is best to know some winter, too, so that the summer, when it arrives, is the more gratefully received.”

I turned to face him. A tear ran down from each of my eyes and dripped along my jaw. Stefan stood with his hands in his pockets, right next to the rock, staring up at me gravely. His hair had grown a little, a tiny fraction of an inch, perhaps. I leaned down and put my hands on his shoulders.

“How strange,” I whispered. “I have just been thinking the same thing.”

He reached up and hooked me by the waist and swung me down from the top of the rock.

“Hush, now,” he said, between kisses. “Annabelle, it is all right, I am here. Liebling, stop, you are frantic, you must stop and think.”

“I don’t want to think. I don’t want to stop.” I kissed his lips and jaw and neck, I kissed him everywhere I could, wetting us both with my tears. “I have been stopping all my life. I want to live.”

“Ah, Annabelle. And I would have said you were the most alive girl I’ve ever met.”

“That’s you. You have brought me to life.”

Stefan paused in his kisses, holding my face to the sunlight, as if I were a new species brought in for classification and he had no idea where to begin, my nose or my hair or my teeth. “Tell me what you want, Annabelle,” he said.

“But you know what I want.”

He took my hand and led me up the slope, where a cluster of olive trees formed an irregular circle of privacy. He urged me carefully down and I put my arms around his neck and dragged him into the grass with me. “I thought you had gone off with her,” I said, unbuttoning his shirt.

“What? Gone off with whom?”

“The honey-haired woman, the one you used to make love to.”

He drew back and stared at me. “My God. How stupid. What do I want with her?”

“I don’t know. What you had before.”

“What I had before.” He lowered his head into the grass, next to mine. His body lay across me, warm and heavy, supported by his elbows. “You are the death of me,” he said softly. “I have no right to you.”

“You have every right. I’m giving you the right.”

He turned his mouth to my ear. “Don’t say that. Tell me to stop, tell me to take you home.”

“No. That’s not why you came for me, to take me home.”

He lifted his head again, and his eyes were heavy and full of smoke. “No. God forgive me. That is not why I came for you.”

I touched his cheek with my thumb and began to unbutton my blouse, and he put his fingers on mine and said, “No, let me. Let me do it.”

He uncovered my breasts and kissed me, and his hands were gentle on my skin. “So new and pure,” he said. “I don’t think I can bear it.”

I spread out my arms in the warm grass.

“God will curse me for this,” he said.

“No, he won’t.”

He kissed me again and lifted my skirt to my waist. I hadn’t worn stockings or a girdle. He worked my underpants down my legs and leaned over my belly to touch me with his gentle fingers, in such an unexpected and unbearably tender way that my legs shook and my lungs starved, and at last I made a little cry and grabbed his waist, because I couldn’t imagine what else to hold on to. His shirt was unbuttoned and came away in my hands. “Tell me to stop, Annabelle,” he said.