Outcasts of the Islands: The Sea Gypsies of South East Asia

‘We will go over there, sana, and put down the net,’ and we resumed our lugubrious progress. The tranquillity seeped into my body, the heat, the rhythm of the pole moving us forward in spurts, each thrust like a slow pulse, the water in the dug-out washing back and forth, rushing towards Sarani as he pushed on the pole and the bow dipped, flowing back between strokes. I timed my baling to coincide with the flood at my feet. The crab went over the side. I felt like a young boy given a simple task vital to the enterprise, given a stake in it.

Sarani talked. ‘That’s Si Amil. You can’t see Danawan, but it’s only as far away from Si Amil as we are from the boat now. When we came from Bongao we stayed at Danawan for a time. We were three boats, three motor. We had not used lépa-lépa for a long time already, although I was born on one and I have built more than ten in my life. Pilar was still small, but his older brother Sabung Lani was already married and had his own boat. There were many Bajau Laut there already, and many House Bajau in the village. There used to be many fish too, but then people started using fish-bombs.’ (The phrase main bom, ‘playing bombs’, like main futbol or main badminton.) ‘Suluk people. Bajau Laut people only use nets and spears. We are frightened to use bombs. They’re dangerous and illegal. Now there are no big fish left at Danawan. We were the first to come to Mabul, and then other boats, and then the people in the village and now kurang ikan, few fish’ (kurang can also mean ‘not enough’). ‘We will put the net down here.’

Sarani found the end of the net, a monofilament gill net about four feet deep, and snagged it on a coral head using his pole. Propelling the boat with one hand, he teased out the mesh with the other. ‘It’s going to rain,’ he said, and pointed with the pole to the dark clouds rolling off the hills of the distant mainland.

‘My first wife was still alive when we came to Danawan. We already had seven children, well, eight, but one died in the Philippines when still a child. Take the net off that snag, can you? She is buried in Labuan Haji, on Bum Bum. She had family there. When Pilar got married I could have stayed with him, but a young couple should have their own boat. So I built another boat and got married myself. Why not? I was still strong, for pulling up nets, for playing love, main cinta.’ I watched the muscles working across his shoulders, baked dark chocolate, his sturdy body and powerful limbs. He was still strong, his fingers thick and worn, his feet broad, their soles bleached by salt water. ‘It is unusual for someone already old to marry a young woman, but I knew Minehanga’s father and he said yes, though only if she said yes. I paid a higher bride price, about sixteen hundred ringgit (£400), some cash, some in goods – rice, salt, cloth, tobacco. What is the bride price in your country? You don’t have one?’ and when I explained the old custom of the dowry he let out a long ‘oi’ in surprise. ‘Good, if you’re a boy. This boy getting married tonight, his family have paid one thousand ringgit, twelve hundred maybe, to the father of the bride. Here, it’s good to have daughters.’ He paid out the last of the net. A lump of polystyrene went over the side to act as a marker. We drifted away from it as Sarani prepared another plug of betel. We turned and backtracked slowly along the length of the net some ten yards away from its line of floats and Sarani rattled the pole underneath the coral heads to frighten fish towards it. Shapes of fish shot away from the stick, and sometimes their flight was stopped abruptly by a wall of monofilament. We turned again at the anchored end, turned towards the mainland. The clouds were over the sea and the patterns of the rain showed on its surface. ‘It’s going to rain, soon,’ said Sarani as he put on a pair of goggles, made of wooden frames and window glass, and slipped over the side.

He started to swim back along the net, his face under water, pulling the dug-out behind him. He ducked down, the white soles of his feet kicking at the surface. His head came up, as smooth as an otter. He clutched a fish in his hands which he threw into the boat, followed by another. A pair of goatfish flipped around at my feet. They raised and lowered spiny dorsal fins. The large scales of their flanks were nacreous below a black lateral line, a black dot near the tail, and above were shaded yellow. I watched them dying and remembered the colours of mackerel fresh-caught, the moment of regret, and as the goatfish weakened, a colour the shade of pomegranates seeped over them as though their scales were blotting paper. The sky ahead was purple now, but we were still in sunshine, lighting the turquoise shallows, turning the emerging sands of Kapalai into a bar of pale gold. The colours were so intense, the crimson fish against wet wood, Sarani’s brown back in the turquoise water. A wrasse landed in the boat, bright blue spots, ringed with black, on a chocolate brown field, a triggerfish, back half yellow, front half black, that seemed to talk, tok tok tok tok. More blushing goatfish, as the first two faded to grey, even the black markings only just visible, as though their normal coloration had been sustained only by an act of will. A polka-dot grouper and a parrotfish, lime green with purple trim. ‘Kurang ikan,’ said Sarani and he climbed back into the boat. We pulled up the net in the rain.

The wind had brought us the sound of it, white noise hissing across the sea. The light became livid, the colours dead. Kapalai disappeared, drenched behind a curtain of rain which we watched sweep on towards us across the shallows, seemingly solid. In its midst the wind was chill and the noise ended conversation. Water ran from my head in streams. The surface of the sea seemed to pop with pearls, the drops rebounding. And then it had passed and we could not see Sipadan any more. Sarani unsnagged the end of the net and began to propel us towards a deeper part of the reef; the hull of the canoe was beginning to catch on the larger coral heads.

‘There are lots of fish at Sipadan, big fish, turtles, but we do not go there any more. It is not allowed, not since the resorts came. No one can fish there. We cannot go close. Do the tourists take the fish when they are diving? They are also not allowed? Hmm. They only look? Why? You do not have these things in your country? What is it like then?’ and I told him about cold, coral-less seas, rocky coasts and kelp forests, islands that have no palm trees and see snow in the winter. ‘Ice from the clouds? And the girls must pay for the boys? What a strange place.’ Sarani paid out the net again.

As soon as the storm had passed I could see a small flotilla of pump-boats streaming across the open sea from the direction of Bum Bum. They grouped at the far edge of the reef, six of them, two figures in each boat, and spread themselves out around the drop-off. I thought nothing more of them, fishermen. The net was down and Sarani was back in the water looking for shellfish. Cone shells – dolen – came over the side, lambis shells, kahanga, that look like one half of a Venus fly-trap, a pink-slitted hollow with five delicate tusks curving out from its lip. They landed higgledy-piggledy, but after a while the pile began to move as the molluscs tried to right themselves. A long, red-brown claw emerged from the slit, and a pale olive mantle flecked with white unfurled over the smooth inner surfaces. Horns poked out. The claw slipped round the edge of the shell and hooked powerfully, looking for a purchase. Those that were the right way up were dragging themselves along the bottom of the boat, mingling with the dying fish. Sarani collected sea-urchins too, téhé-téhé, not the vicious black ones with eight-inch spines whose tips break off in a wound, but ones no more prickly than a hedgehog, with feelers between the short spines that attached themselves to the palm of my hand. The bottom of the dug-out was beginning to look like an aquarium. Sarani found a large clam and set about opening it on the spot. He smashed an opening with the blunt edge of his parang, cut the muscle holding the halves of the shell closed, and quartered the contents. ‘Kima,’ he said. ‘It’s delicious, if you have some lemon juice, some chilli, some vinegar, some garlic, some Aji No Moto.’ (Sarani used the local brand name for monosodium glutamate.) It was better without, tougher than an oyster, and as salt as the sea.

When I first heard the noise I thought it was thunder, but the sound was too percussive, too short. The sun had come out again and the clouds were white and broken. ‘Main bom,’ Sarani explained, pointing to a pump-boat far behind us. The boat closest to us had its engine going, cruising over the seaward drop-off where, in theory, the big fish lay. It would slow at intervals so that the man in the front could put his head over the side. He signalled them on until they were far in front of us. Against the glare of the sea I saw a figure stand and pitch a speck out in a lazy arc over the water. The figure sat down. A beat, and then the water near the boat shivered and rose in a spout twenty feet high. The boom came last. ‘You see? Playing bombs.’ Sarani could not tell me exactly what a fish-bomb was, but he knew the effects of one well enough. ‘All the fish die, the young fish, the small fish that the big fish eat, all the coral, all the animals that the small fish eat, dead. You see? Kurang ikan. We are hungry. Before, this canoe would have been half full already. We cannot stop them. If we fight them, they come to our boats and throw bombs inside. I have seen this happen in the Philippines. Kami rugi, we are the losers.’ He pounded a betel nut with feeling.

Four of the goatfish were prepared for cooking, Minehanga cutting them roughly into lumps with a parang, while Sarani deftly gutted the rest of the catch, splitting the head and cutting in by the backbone, opening the fish out like a butterfly’s wings. These went into a bowl to salt before being laid out on the deck to dry. Minehanga had boiled the fish. There was no lemon juice, no garlic, no vinegar, no chilli, no Aji No Moto, not even any salt in the water, just plain boiled fish. It was served with more cassava damper, made from a tuber that is almost pure starch and produces a flour that turns into a glutinous pancake when baked in a dry wok. The cassava was hard work and I wondered how Sarani managed to get through it with only gums. The fish was boiled to smithereens. Sarani at least had no trouble with that; nor did Mangsi Raya, but then she already had double his tooth count. The bones went over the side. The bowls and our hands were washed in the sea. The rim of my glass of tea tasted of salt. Sarani stretched out under the awning, chewing betel, resting on a pillow. In the heat of the afternoon only the children were active. Even the fish-bomb detonations became infrequent. We were afloat again and the boat stirred with the water, its motion acting on me as quickly as a drug. Planks of wood had never been so comfortable. I fell asleep thinking about the pillow … and lice …

I was more wakeful after the wedding. We had returned to Mabul in the evening to join in the celebration of the village nuptial. The music continued under the palms long after we had returned to the boat, past the setting of the moon, and complemented the rhythms as it rode at anchor with its bow to the wind. The waves clunked under the hull. The boards creaked as the bow rose. The loose glass mantle of the oil-lamp clinked. It was soothing, until the elements of the polyphony began to change. The creak lengthened and multiplied. I could no longer hear the oil-lamp clinking over the noise of the flapping tarpaulin. Pots rattled. A glass tankard toppled over and rolled back and forth, the handle stopping it after a half-turn either way. The wind was cold and it had come around.

No one else was awake. Mangsi, cradled in a sarong hanging from the roof-tree, was still as a plumb line. The others seemed to be attached to the deck with Velcro. The wind promised rain. Sarani stirred in response and came forward nimbly on his hands and knees. He knelt in the bow, braced against the gunwale, and began to pole the bow round into the wind. Unbidden, I seemed to know what to do. I stumbled forward to the anchor rope and began to pull. I knew when to stop so that Sarani could go aft to cast off the stern line. I pulled us up to the anchor as he came forward again, and then hauled it onto the gunwale while Sarani, standing now, punted the boat out to deeper water. He nodded and I let it go. He stowed the pole, and took the rope, setting the anchor and tying off the line over the projecting bow and an iron spike driven into the stem. The sky was dark with clouds. The first drops of rain felt sharp and cold on my back. We turned our attention to the waterproof sheet that rolled down to close off the forward opening, tying the corners to lumps of coral that doubled as net weights. It was raining hard by the time we slipped round the sides of the sheet and under cover of the tarpaulin. The rest of the family were still asleep.

The two of us sat in silence, drenched, and watched for leaks in our shelter. The wind flapped under the sides of the tarpaulin and blew in gouts of rain. Sarani tied them down. We moved all the soft furnishings away from their usual stowage along the gunwales, bundles of clothes, pillows, a plastic shopping basket full of knick-knacks and hair oil. Minehanga woke up and moved the children, though they stayed fast asleep. Sarani dried himself off with a sarong which he then wrapped around himself. He reached for his betel box. We waited grimly for the storm to pass. ‘I’m going to build a roof,’ he said.

The rain died away, though the wind remained strong. As I lay down on the damp boards I could hear the wedding organ start up again. I had to admire their stamina. Sarani spat out the betel dregs and moved aft to the bilge pump, a contraption of grey plastic waste piping that projected above the deck with a ram made from shaped flip-flop rubber attached to a stick. He set up a steady counterpoint to the music until the bilge sucked dry and he settled down to sleep again. We had gone through the whole procedure almost without comment. We had worked together for the boat, satisfied its demands with promptness; a dragging anchor is not a piece of guttering blown down in the night that can be left until the weekend. What did the people ashore know of a rough night at sea? The wind in the palms, the thatch rustling, a child moving closer for warmth. The newlyweds, asleep now maybe, would know as soon as a baby came what it is to tend a boat through the night. Sarani, who had been born on a lépa-lépa and had spent no more than a handful of nights ashore in his long life, took rest when he could in a home that needed pumping out four times a day, propping up on a falling tide, battening against weather.

The kettle was on, and Minehanga was breastfeeding. Sumping Lasa had taken over the sarong cradle and was using it as a swing. Arjan was running around on the afterdeck looking for things to throw overboard. Life did not stop because we were underway and by the time we reached Kapalai Minehanga had dealt with a tantrum from Sumping Lasa who had been pushed out of the swing by Arjan, a puddle on the planks courtesy of Mangsi Raya, and the attentions of the hungry boy as she peeled plantains for breakfast. Sarani stood in the stern, one foot on the tiller, scanning the lightening horizon.

We arrived at Kapalai as other Bajau boats were returning from pulling up their nets, Pilar’s amongst them. He anchored close in behind us and began to sort out the pile of net on the bow, paying it out again, to wash it in the shallow water. While Minehanga made up a batter for the plantain Pilar transferred his catch of blue-spotted ray into the dug-out behind our boat, some still lashing the air with barbed tails, and set about gutting them. The tails went first and were flicked over the side of the canoe. I made a mental note to watch where I walked at low tide. The eyes and gills were removed like an apple core. The ray were hung out to dry on a pole. Pilar broke off to eat breakfast with the rest of us.

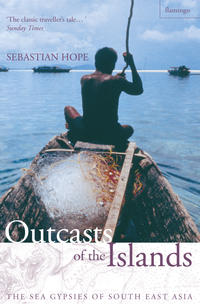

The sun was already hot and its strength was redoubled by the glare from the water. I retreated to the shade of the awning, only too aware after a night on the boards of the sunburn I had suffered the previous day. I could not go fishing. I watched from the boat as Sarani poled away in the dug-out over the bright shallows until his figure, standing in the bow of the canoe, became a silhouette at the edge of the reef against the empty eastern horizon.

The fleet had reassembled around us and in this social hour of the morning canoes plied between the boats, paying calls, returning a borrowed bowl, bringing food, others heading for the fishing grounds on the falling tide, collecting a pole or a paddle or a parang. We had our fair share of curious visitors. I listened without understanding to the lilting cadences of the language that seemed at odds with Minehanga’s sharp voice, listening for something that sounded familiar. I wondered how the two of us would get on without a common language. She spoke no Malay; I would have to learn Sama. This was my first time alone with her and I had no idea what she thought about my presence in her home. As helpless as one of her children and with a smaller Sama vocabulary than even Arjan, I had invaded her nest like an outsized cuckoo chick, an uninvited mouth to feed. She talked loudly and slowly at me, showing her buck teeth, and I felt like a Spanish waiter being mauled by a British tourist. I struggled to pick out something that I understood. Melikan was a word that had come up again and again in her conversations with the visitors. Now she was saying it and pointing at me. Half of it sounded familiar; ikan is the Malay word for ‘fish’. Was I expected to go fishing as well? It began to dawn on me that Melikan referred to what I was rather than what I was supposed to do, that it was a corruption of ‘American’ and meant ‘Westerner’ in general. And so I was named. She would say ‘Melikan,’ and point to a sarong near where I sat and I would pass it, or ‘Melikan,’ miming striking a match and I would proffer my lighter. We rubbed along.

Sumping Lasa was still scared of me. I only had to look at her and smile to send her running to her mother’s side. Mangsi Raya cried the moment she was more than a yard away from Minehanga. Arjan was more bold. He would run up to me, shout and run away chuckling, making the boards jump in his wake. Minehanga told him to stop, but he did not and on his next sortie he bumped into Sumping Lasa. She landed hard on her backside and started to cry. Arjan got a cuff round the ear and joined in. After the first few gusts of tears Sumping Lasa got up and went over to Minehanga for attention. She stood next to her mother, her hands cupped behind her ears, her mouth open wide and silent as her convulsed face began to redden. The silence was agonising, her face a mask of pure grief. It went on. Her mouth opened wider. And then the full force of the tantrum struck. She let out an awesome bellow, almost as long as the silence, followed by another and another. She had her mother’s voice. When it became obvious that Minehanga was not interested, she started hitting Mangsi Raya, who was startled by the surprise attack and began to cry as well. Whereupon Sumping Lasa got a clip round the head and doubled her efforts. Mangsi Raya stopped crying the moment the nipple touched her lips. Arjan knew he had won and dried his eyes. He started running up and down the boat again, his upper lip glistening with snot, taking care to avoid Sumping Lasa as she drifted around in a blur of tears, slapping my foot each time he passed. Sumping Lasa started drumming on the boards with both feet, running on the spot until she fell over. In the midst of the mayhem I caught Minehanga’s eye and we smiled.

‘Kurang ikan,’ was all Sarani had to say about his fishing, ‘but today there is no one playing bombs. Maybe they thought the wind would be strong, like last night. You were scared, no?’ He laughed at the memory. ‘It is not the season for strong wind. In this season, the wind comes from there’ – he pointed north – ‘and in the other season it comes from there’ – the south – ‘and that is when there are strong winds. Normally in this season we stay on the other side of Mabul and on this side of Kapalai.’ I was keen to find out their range, to find out just what sort of a ride I could expect. ‘We fish here and at Mabul. Then there is one reef past Mabul, Padalai, just a reef, no island. We go there sometimes. There is one more reef towards Danawan, called Puasan. The Bajau Laut from Danawan also fish there. After that? The season of the south wind comes in two months more [dua bulan, literally ‘two moons’]. We stay here for a time after that, maybe one moon, and then we go to the islands near Sandakan to catch shark. When the season changes we come back here.’ It seemed extraordinary to me that Sarani could tell me exactly how his year was spent, exactly when the south wind would come, and yet not be able to say how old he was. I asked him how old Arjan was, thinking he would be able to remember how many times he had been to Sandakan since his birth, but he did not know that either. It was almost as though there was some taboo surrounding age that prevented him from saying if he knew, or maybe from even reckoning age at all. I could not understand it. Living so close to the Equator and its perpetual equinox means that the length of days and nights does not vary much year round. The words ‘summer’ and ‘winter’ do not have a useful meaning. But the Bajau Laut live in a world full of other time signals, just as regular, just as significant. There are two tides a day, a full moon every twenty-eighth night, and a change in the prevailing wind every six months. These events are so central to the pattern of their life that it seemed inconceivable to me they would not tally them.

But then why bother counting? When the tide falls you prop up the boat. When the moon is full you go fishing at night. When the wind changes you move your anchorage. You do not have to plan beyond the next tide and the next visit to the well; there is no need to lay in store for winter, as there is no winter. There is no need to know how old you are. When you are big enough you learn to swim and paddle a canoe. When you are strong enough you help with the fishing and the housework. When you reach puberty you work and wear clothes. When the bride price has been raised you are married. While your strength lasts you are parent and provider. When your strength fails you do what you can to help. These are the only markers of time that make any sense, the events of a personal history, and there is no need to count them as they happen only once. I would ask Sarani when things happened and he would say, ‘I was already wearing shorts,’ or ‘Before my first wife died,’ or ‘While I was still strong,’ or ‘When the coconut palms were so high,’ or ‘Before Kapalai was washed away.’ These were the singular events against which his time was measured.

The heat had gone out of the afternoon and Minehanga had been busy while we were talking. She had cooked up the dolen Sarani had gathered – the téhé-téhé had been given away. A steaming dish was brought out to the bow, the motive claw of each mollusc projecting now that it had been boiled, and forming a dainty handle by which to pull it from the conical shell. They tasted like whelks. ‘Kahanga are better, but we save them for market.’ The empties went back into the water, waiting for squatters; eventually the dead shells would rise up and walk away on the legs of hermit crabs.

Pilar came back from the reef and began to sort out his deepwater net. We went with him when he set out to the south-east to lay it off the Ligitan Reef. We talked more after a supper of boiled fish, sitting out on the foredeck in the darkness before the moon rose. The boat bobbed in the light breeze. Arjan came out to join us, sitting in the crook of his father’s legs and banging on the Tupperware betel box. Minehanga was singing Mangsi to sleep, a lullaby sung in her raucous voice above the soft noises of water and air, but it was strangely soothing in the glow of the oil lamp.