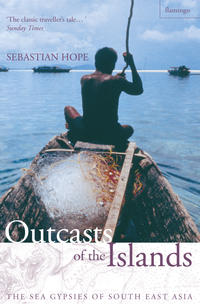

Outcasts of the Islands: The Sea Gypsies of South East Asia

‘What will you do, Panglima?’

‘Massage.’

‘Massage only?’

‘There are words.’

‘What kind of words?’ Sarani looked blank.

‘Are they magic words? Islamic words?’

‘No.’ Sarani knitted his brows. ‘But they are special words.’ He studied the bedspread, tracing the pattern with a thick finger.

‘And massage and words will make vanish her pain?’

‘Kalau Tuhan menolong, if Tuhan helps.’ What the nature of Sarani’s power was, whether it was given or learned or acquired, its extent, remained unclear to me. More puzzling was his concept of Tuhan. This Malay word for the ‘Supreme Being’ is most often used as a name for Allah. Was that the way Sarani was using it? He had used the same phrase when I questioned him about the washing ceremony I had witnessed outside Jayari’s house, ‘if Tuhan helps’, but it had not sounded like a translation of the Arabic insha’allah, ‘God willing’, then either. The Muslim deity wills things so; Sarani’s Tuhan helps.

When we met later I had already visited the pharmacy. Sarani was impatient for his medicine.

‘So you tear it open like this, and inside is one fruit.’ My primer offered no suggestion on the correct number qualifier for condoms. Buah, ‘fruit’ seemed closer than biji, ‘seed’.

I looked at the wrapper for instructions in Malay, a diagram even – something that would help me explain – but the picture on the front of a fully-dressed modern-looking Malaysian couple embracing would not exactly spell it out for Sarani. The condom emerged from its amnion, glistening and wrinkled, and unfurled itself on my palm. I held it out for Sarani to see. The teat erected itself expectantly.

‘It looks like a jellyfish,’ was his only comment. I had a long way to go.

‘And then you put this on the end of your botok, when it is big, before you put it into the puki,’ I had learnt the right words. I had the condom over two fingers. I was trying to remember the wording of the Durex instruction booklets I had studied in anticipation during my adolescence. ‘You have to make sure there is no air in the top.’ I think that was the way it went. On an empirical note: ‘You have to make sure it is the right way up. Then you roll it down like this, but you have to be careful the bit you have unrolled does not go under the bit you are unrolling or else it won’t unroll any more. You see?’

‘What?’ said Sarani.

‘Never mind. So you roll it all the way to the bottom, as far as it will go, and then you are ready for playing love.’

‘And after?’

‘And after the mani has come out, and before your botok goes small again, you take it out of the woman.’ I couldn’t bring myself to say ‘Minehanga’. ‘It is best to hold the bottom when you are doing this.’

‘And then I can wash it?’

I told him he must throw it away; at least the condom, if not the wrapper, was biodegradable. I told him that if the wrapper was broken, or punctured, then the medicine would not work and he must throw it away without using it. I threw my demonstration model in the bin to underline the point. He nodded and stowed the packets in the belt-bag under his shirt. It seemed a little late in the day to be giving contraception lessons to a father of eleven, but perhaps my absence from the boat that night would give him the opportunity to practise. We went to look for hurricane lamp parts. Maybe he was planning a night of fishing instead.

In the late afternoon when the tide had again covered the stinking flats, I waved goodbye to Sarani and his family and hangers-on, as he cast off from the kampung air, Pilar’s boat laden with supplies, and Sumping Lasa said her first words to me. As they backed away from the dock, she came running out onto the bow deck in her best frock still wearing her flip-flops, and she waved to me. ‘Bye-bye,’ she said. ‘Bye-bye.’

Three

The greatest luxury ashore was access to a bathroom, though I had quickly accustomed myself to arrangements on the boat. You pee over the side, you crap through the gap in the stern boards, left for that purpose. Sarani would say, ‘Mesti buang tahi, must throw out shit,’ as though ditching ballast, and move aft to the dark stern with the baler for company. Minehanga always had the cover of her sarong. The children were sat over the edge of the gunwale while they off-loaded, their bottoms washed with sea water, the planks washed down with sea water when they did not quite reach the gunwale in time. Sarani could pee over the side from a squatting position by the gunwale, lifting up one leg of his loose fisherman’s trousers. I did not have the balance to be able to do this on a rocking boat. I was forced to stand. My appearance on the bow deck at any time would draw curious stares from the other boats. To stand up there with your old boy out, trying to keep your balance and ignore the watching eyes, the comments ‘Look, he pees standing up!’ – cannot pee, more like – was not an easy matter.

Washing was done at the stern, sluicing with sea water and rubbing with the free hand, a rinse with fresh water if stocks allowed. Sarani’s skin felt dubbinned to the touch, oiled against the sun and the sea. The bundles of clothes gave off the smell of clean unperfumed bodies; the boards were smoothed by the rubbing of skin, and held the odour of people; the pillows had the comforting scent of hair. In the Semporna Hotel, the foam bedding smelt of night-sweat.

I met Ujan and Mus at the Marine Police post, and the three of us adjourned to the bar. The conversation turned to fish-bombing.

‘You know what they use? These,’ said Ujan, indicating the beer bottles. ‘Maybe you will see these ones again at Kapalai in a couple of days. They fill them with a mixture of fertiliser and petrol. Then they plug a detonator into the top, light it, wait a moment, throw it into the water, and boom.’ He laughed as he tapped the top of the lager bottle with the bottom of the other and froth raced up the neck and out, Mus hurrying to tip it into his glass. ‘You have seen the men who waited too long? In the market maybe? No right arm and a lovebite on the side of their face?’ Ujan poured half-and-halves, Carlsberg and Guinness.

‘It is very difficult to catch these people,’ Mustafa confided. ‘On the sea, they can see us coming a long way off. They just throw the bombs overboard, pick up their fishing lines, and move onto the shallow reef where we cannot follow them. The materials are so cheap and easy to find. You can make one at home. You have to get the proportions right, or else it is very unstable, but they know how to mix it. The detonators come from the Philippines, but they are home-made too, made from a bundle of matches around a small charge of explosive. You can buy them here for one ringgit each. We try to catch the people who bring the detonators across, but they are very small,’ he held up his little finger. ‘You could fit ten into this cigarette box. Oh yes, we catch plenty, but there are always enough that get through. What can we do? It is a big ocean. Sarani doesn’t bomb fish, does he?’

‘No, he says it is the Suluk people.’

‘Bajau also, Indonesian also, mainly it is the illegal immigrants.’ The immigration problem extends Malaysia-wide. Illegal immigrants were blamed for most anti-social crimes, I noticed from the newspapers: prostitution, mugging, smuggling, drug-dealing, car theft, burglary. Those who broke no further law after their illegal entry still faced deportation, in theory at least. Occasionally there were sweeps, ‘checkings’, followed by mass deportations, but the immigration laws are flouted at every level, from the ruling party handing out Malaysian documents to Muslim Filipino and Indonesian migrants at election time, to illegal Bangladeshi construction workers on prestige projects like the new Kuala Lumpur airport and the twin Petronas Towers, to loggers and plantation labourers in Sabah.

‘Sabah would close down if there were no illegals,’ said Ujan.

Unfortunately, the threat of deportation promotes the use of fish-bombs. If you were a poor fisherman who had left the Philippines with your family to make a living in Sabah, and you knew there was always a chance you could be caught tomorrow and sent back with only the clothes you had on, would you invest capital in nets and lines? Or waste what might be only a short time in these waters trying to catch fish by those laborious and uncertain methods, when for an investment of three ringgit, bomb and detonator, you can blow up twenty ringgit-worth of fish in an instant? And why should you care, while your luck holds, whether there will be any reef or fish left in a year’s time? It is not hard to understand the reasons people use fish-bombs, but it is very difficult to sympathise with them.

The speck on the horizon that I had glimpsed between the islands of the channel I took to be a large boat that had anchored off Mabul, maybe a naval patrol, or a freighter from Tawau. As we rounded Manampilik, and passed by the southern edge of the Creach Reef, I could make out five masts towering above the shape. Except they were not masts. Closer, it became apparent that they were legs; in the short time I had been absent from Mabul, someone had moored an oil rig 500 yards offshore.

I was returning on Sabung Lani’s boat, Sarani’s other son. He had no idea why it was there, but then he had no idea what it was either. I explained where diesel came from, and he brightened. He needed fuel. He always needed fuel. His boat was packed with people and their luggage; he was collecting passengers for the run across the border to Bongao. His own family was large, and his boat was no bigger than Pilar’s. He had come forward over the roof to sit with me, scattering girls singing their heads off amongst the nets. I shared their joy, to be on the sea again, in the warm light of the afternoon, knowing this time what lay ahead of me, and relishing the prospect. Sabung Lani sat close.

‘So you are sleeping on my father’s boat?’ He spoke gentle Malay. He always referred to Sarani as bapak saya punya, ‘father I have’, an elegant colloquialism to which he gave a humble and reverential intonation. I felt an immediate sympathy with Sabung Lani; he too suffered from acne. He looked like an older version of Pilar, heavier, and while they both had Sarani’s gentle eyes, Sabung Lani’s did not have his father’s mischievousness, nor Pilar’s sparkle. They had a sad expression, a memory of pain now distant. He was about forty years old, and had had eight children already with his large wife Trusina. The first six were girls.

‘You must spend a night on my boat, brother,’ said Sabung Lani, and I wondered if there would be room. ‘You want to come with me to the Philippines?’ It was a tempting invitation but the danger involved gave me pause for thought. ‘You will be safe on my boat.’ I said I would ask Sarani.

‘Bye-bye,’ said Sumping Lasa waving uncertainly, standing on the bow in her dirty green dress, still holding her flip-flops. From under the tarpaulin came the sound of rattling planks, and a musical shout of ‘Da’a, Don’t!’ from Minehanga as Sabung Lani’s boat, engine cut, glided in under way. Arjan, naked, burst out onto the bow. ‘Melikan, Melikan,’ he was shouting. He had both arms stretched out towards me. Sarani followed, all smiles. It seemed that they were as happy and excited to see me as I was to be back. This felt like the real beginning.

‘He’s been asking all the time, “Where’s the Melikan, where’s the Melikan?”. Careful,’ said Sarani as he helped me aboard, ‘there is Mbo’.’ Arjan was clamouring for me to pick him up. I stood on the bow with the little packet of naked sun-warm skin wriggling in my arms, and looked out over the fleet, the boats clustered in twos and threes, more than twenty, Pilar astern of us, and Sabung Lani poling forward to anchor ahead. People waved at me from other boats, ‘Oho, Melikan,’ shouted Timaraisa and her children, and I was taken back into the arms of the water-borne community. Arjan was trying to put something in my mouth with his snotty fingers. I accepted the gift, a morsel of shark jerky.

I put him down, and he was off, making the boards rattle under his vigorous little feet. ‘Da’a,’ Minehanga shouted again. Mangsi Raya was asleep. Sumping Lasa joined in the noisy fun. ‘Da’a,’ said Sarani, and grabbed Arjan on his next pass and gave him a smack. He sat down hard. It had to be serious for Sarani to become involved. Sumping Lasa had escaped to the stern and Minehanga had to go after her, calling across to Timaraisa, who paddled over in a dug-out. Both children were taken away. Mangsi Raya had woken and, finding her mother absent, she started crying.

‘Naughty kids,’ said Sarani. ‘They’ve been running around all day, disturbing the Mbo’. And now crying.’ A pandanus mat had been set up forward in the cabin, one end tucked over the tarpaulin’s port wall-strut, and adjusted so that the other end hung down onto the deck and formed an apron stage for the offerings, for the seat of Mbo’. On the overlap sat an old coconut in its brown leathery husk and a portion of unthreshed rice. The rice was contained within a band of bark over which had been placed a square of black cloth, and the rice poured in on top to make a pool of yellow grains. Simple, but specific, offerings on a simple altar, but offerings to what, to whom? I was eager with questions, but first I had to discover how to behave during the period of Mbo’.

‘No, no, it’s no problem that you are here,’ said Sarani, ‘but be careful with your feet. You can lie with your head near the mat, or sit near it, but do not point your feet towards it. Do not make a lot of noise like those naughty kids. There are other things which will disturb Mbo’, if the wind is too strong or the sea too rough. We cannot go anywhere in this boat, or start the engine, or do any work in the boat while there is Mbo’. On the first day, in the afternoon, we start Mbo’ Pai, and put out the rice and the coconut. It stays there tonight, and in the morning, we will pound the rice and grate the coconut, and cook them together. Everyone eats. Then tomorrow we can do nothing also, one more night the mat stays there, and in the morning, finished.’ I had missed the dressing of the altar and the consecration of the offerings. Sarani told me it had been accomplished by the old couple I had seen perform the ceremony on my first morning at Mabul. They spoke words, Mbo’ words, over the coconut and the rice.

The objects themselves excited questions, both land products, both enclosed within a husk. Why would a maritime people make an offering of land crops? I would have expected an offering of something from the sea. These objects would not have been out of place on a farmer’s fertility altar; did they point to an agrarian origin? Why rice? Unhusked rice? The coconut was less out of place, but Sarani told me it is only as part of the Mbo’ meal that the Bajau Laut eat old coconut.

And what was it that connected the two, that fitted them to be offerings? I suspected that it had something to do with the husk, with the fact that the outer part must be stripped away to reveal the inner. The only other (overtly) ancestor-worshipping culture I have observed in South East Asia was that of the inveterate betel-chewers of western Sumba, a rice-growing people. As part of their annual fertility rite, they make offerings at the megalithic graves of their ancestors of sirih pinang – a whole betel nut, a thin green fruit that looks like a large immature catkin, and lime powder. For the Sumbanese, the symbolism of the offering is manifest: the betel nut, very much like a miniature coconut, is the womb; the catkin stands for the penis; the white powdered lime for the fertilising seed. There were similar elements here, the fertile hollow of the coconut and the myriad grains of rice the sperm.

Sarani was not strong on symbols. ‘Sometimes we make Mbo’ Pai when someone is ill, and you must make Mbo’ Pai before a wedding, but this kind is one that we do from time to time for good luck.’ Nasib was the word he used, meaning also ‘fate’ and ‘fortune’. ‘Good luck for fishing, for health, for the boat.’ I wondered if there was an element of animism at work, if the boat had a spirit that could be protected and strengthened through the observance of ritual. I had seen such a ceremony performed in another part of the Malay world, a shamanic cleansing and fortifying of a house-spirit, a spiritual spring-clean.

‘No, of course the boat does not have a ghost.’ I sensed he was getting irritated by my questions, but I had to ask how the ceremony was thought to work.

‘No, the ancestors do not come here.’

‘Where are the ancestors, Panglima?’

‘Their spirits are with Mbo’. Mbo’ is the first ancestor. He comes here.’

‘And the ancestors made the same offerings?’

‘Oh, yes. They did it like this, so we do it like this the same.’

‘And if you do this, you will thrive?’

‘Kalau Tuhan menolong.’

Sarani was the first to wake and he set about the third act of Mbo’ Pai. He emptied the rice onto a winnowing tray, and took it aft to where Minehanga and another woman were waiting by the rice mortar, carved from a single piece of wood. Every boat had one of these, knocking about, sat on, used as a quotidian container, until the time came for it to assume its ceremonial role. Sarani emptied half the rice into the hollow and the two women standing opposite each other, each with a foot on the base, drove double-ended pestles as tall as themselves into the mortar in turn, one two, and the boat’s sounding boards gave back thump thump, thump thump. The first light of day reached us through the palms of the island as the rice was winnowed over the stern.

Minehanga tore the husk off the coconut and split it with a parang. She squatted on a block of wood to which was attached a cruelly toothed metal spur and ground the coconut against the bit, catching the grated flesh in a bowl below. The mixture of rice and coconut was put on to cook. Everyone on the three remaining family boats partook of the meal – Sabung Lani had left for Bongao before dawn. The rice had been too long in the grain and made the whole meal taste musty.

The taboo on work aboard the boat was still in force and the injunction served to remind Sarani of all the chores he had to complete, all the improvements he wanted to make. ‘Tomorrow, we will wash the boards, we will take out all the nets, and find that rat. We will wash out the hold. We will wash all our clothes. Then I want to build a roof. Like Pilar’s, plank-board and pitch-cloth, if there is wood. You see, you put supports and then an arched beam across …’ This led him to examine the rickety structure that held up the tarpaulin. ‘But this will have to wait until Sabung Lani comes back. He has a sainso.’ I wondered what on earth a sainso was. ‘You know, it’s a machine from your country. Sainso. For cutting wood.’ A chainsaw, Sabung Lani had a chainsaw. ‘From Si Sehlim the fish agent in Sandakan. He also has an ajusabal.’ This turned out to be an adjustable spanner of gargantuan proportions with which Sarani (or more likely Pilar) would work on the engine. Sarani could not even start the engine by himself.

The nut holding the flywheel onto the engine block was huge and rusted. ‘I want to take the wheel off and put that on.’ He was pointing to a rusting contraption that was sloshing around in the oily bilge, a crank handle that he would mount across the top of the engine, and at the end of the shaft a geared cog and chain set-up that would turn the engine over. The chain sat in a tin soused with oil. ‘Then I can start it myself.’ I cast an eye over the motor, the wads of flip-flop rubber that wedged the throttle lever into place, the tube leading into a plastic five-litre oil bottle that acted as the oil reservoir, the other tube, held up by a piece of string tied to a roof spar, running out of the plastic barrel with a lid and a tap that was the fuel tank – more like a patient in intensive care than a locomotion unit – and I wondered that it started at all.

It was permitted, however, to work away from the boat, and Sarani, on Pilar’s boat, made ready to go fishing on the reef. My sunburn had subsided, and I was glad to be able to accompany Sarani again, if only to get away from his boat; there was something about the stillness and the inactivity aboard during the Mbo’ Pai that seemed preternatural. As he poled out against a stiffening breeze I asked him about the place of his ancestors near Bongao, about his childhood.

‘My father came from Sanga-Sanga. My mother’s family was near Sibutu, but she died when I was still small. I was the ninth of ten children. Three of the others died when they were young. My father was already old and when my mother died he went back to Bongao. It was a dangerous journey before we had engines, the current is very strong. When we got there I did not live with my father. I slept on a different boat with another family. I worked with them and then, when I was just a youth, I hadn’t long been wearing shorts, I worked for the Japanese. They were building an airstrip on Sanga-Sanga Island. They paid us Japanese dollars and then the aeroplanes and the boats of the Melikan came playing bombs, and they paid us Melikan dollars to mend the flying ship place. Your dollars in Italy are the same?’

This was astounding information. I could have asked Sarani how old he was till I was blue in the face, and still be none the wiser, but now, as a result of his desire to show off his Japanese vocab and his curiosity about the international currency market, I could work out that if he was wearing shorts, at (say) the age of eleven, in 1942, he was roughly sixty-five, and fourteen at the end of the war. ‘Some of those Melikan used to give me cans of food, which I sold, and sometimes we went fishing in their boat and I would dive for them. For oysters.’

He was quiet for a moment, remembering. ‘I had my own boat after that. I went out to catch trepang, just working all the time. My father had died. I had no family close by. I ate with the other family, the one from before, but every night I was spearing trepang, and every day I was boiling it and smoking it. I would sit there on the sea-shore watching my fire, and the boys my age would say, “Come, play baseball,” and I would say no and stay tending my fire. There was a girl who would stay with me on the beach sometimes and she … Oh, what was that?’ A ray. ‘We must find poles for those spear heads. We can do that on Mabul tonight.’ He did not resume his story. I asked him what happened next, and he said ‘When? Here, start paying out the net.’

Collecting reef produce is much like collecting wild mushrooms – you have to know what is safe to eat. You have to know what is safe to touch, for that matter; at least mushrooms do not bite you, prick you, sting you or cut you. The biters do not present much of a threat. Reef sharks are timid fish, and barracuda attacks are caused in the main by mistaken identity – look out for that flashing silver bracelet that looks like a fish in distress. Triggerfish are ill-tempered enough to attack an intruder into their nesting territory, but their mouths are small and nutrition is not the object of their biting. There are two deadly poisonous biters, the sea snake and the blue-ringed octopus. The sea snake is one of the most poisonous of all snakes: fifteen minutes to organ failure. Luckily, it is also one of the most docile and bites so rarely that it is not considered dangerous. They also say that its mouth is so small, it can only bite in places like the fraenum of skin between the fingers; I have not met anyone who has tested this theory, although one did swim glancingly across my shoulder once. The octopus lives in deeper waters and is rare. Stingrays, stonefish, scorpion fish, lionfish, rabbitfish all have poisonous spines and all (except the lionfish) live in shallow water. An adverse reaction to any of these toxins could lead to death. Or you can step on a long-spined urchin, or fire coral, or a jellyfish, or a species of cone-shell that fires poison darts. The rabbitfish were not the only hazards in the net as I pulled it in. Sarani pointed out the gill-spines on angelfish, the twin sheathed blades at the base of the surgeon fish’s tail. I had much to learn.