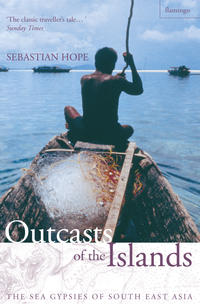

Outcasts of the Islands: The Sea Gypsies of South East Asia

Across the dark sea the lights of the Water Village showed where Mabul lay and reminded Sarani of something that had been puzzling him.

‘Many tourists go there. Woi, many.’ I agreed. ‘I have seen many white people there, men and women, husbands and wives. But I have not seen children. How can this be? Do they not have children? Do they not sleep together?’

‘Of course there are children, but they do not always go with their parents.’

‘They leave their children behind? How can they do that? I could not do that. Arjan would just cry and cry.’ He thought awhile. ‘They have many children? As many as we do?’

‘Sometimes, but usually two, maybe three.’

‘So few? I had seven with my first wife and now three more. It’s a problem for me. I am old, and I have three young children. If they live, I don’t want to have any more. Minehanga doesn’t want to have any more. It is very difficult. I am still strong for playing love. How can they have so few?’

‘Ada obat, there is medicine.’ Obat is a general word in Malay, and takes in herbal preparations and traditional cures as well as what a doctor would dispense. It can also include magic. His expression brightened.

‘Obat kampung? Village medicine?’

‘No, there is a pill.’

‘A friend told me this, but I did not believe him. And I can drink this pill?’ He was eager to join the fertility revolution however late in the game.

‘No, it is for the woman.’

‘Oh, I see. Can I find this pill in Semporna?’

I tried to picture Minehanga with a blister pack in her hand, popping a pill through the silver foil, remembering to do it every day, and could not.

‘It is not just one pill.’ I replied. ‘It is one pill every day and if you forget one day maybe it does not work. Maybe it is not good for Minehanga. But there is also medicine for the man.’

‘Oh? I drink this one?’

How to explain a condom? I did not even have the requisite vocabulary for the body parts involved. I improvised and came up with a gloss along the lines of a rubber sock that stopped the white water from going into the body of the woman. There was pointing involved, hand signals. Sarani got the message.

‘Do you have any of this medicine? Can I find it in Semporna?’

I found myself wondering how sexual relations were conducted in a communal living space, amongst sleeping children and relations, and the answer was: quietly. The boat rocking anyway, the planks creaking, who would notice?

Throughout our conversations Sarani appended the phrase ‘if they live’ to every mention of children. I could imagine infant mortality being high in this environment, but the way he said it was like touching wood, as though to expect them to survive were to be presumptuous. Maybe this was the thinking behind the casual attitude adults adopted towards children, paying them surprisingly little attention, trying not to become too fond of them in case they did not live.

The breeze died away. There were stars down to the edges of the sky, and the waxing moon rose massive on the horizon. In the calm, sounds came clearly from the other boats. Pilar was pumping out the bilge, the handle squeaking. The light from a hurricane lamp brightened to a glare in the stern of another boat where figures moved, lit from the waist down. The lamp was passed down into a dug-out and strapped to the bow. It moved slowly out over the reef. Other canoes followed.

‘They are looking for cuttlefish. When the moon is bright, the cuttlefish come out. When there is no wind you can see into the water. If you have a lamp. Then you can spear cuttlefish and ray and trepang. If you have a spear. My lamp is broken. I have no spear. We cannot go.’ We watched as a canoe slipped past close by, a young man standing in the bow, poling with the blunt end of the spear, his face illuminated from below by light escaping around the metal lampshade. He was peering like a heron into the bright pool at his feet. The shadow of the keel passed over the sand in a halo of light, exaggerating the colours of the red and orange starfish that had crept up on us with the tide. A long-tom burst from the edge of the lighted circle and we could hear it skipping away into the darkness.

‘You can catch long-tom at night, but not with a spear,’ Sarani said. ‘They are frightened of the light. If the light touches them, they run. You can catch them with a net, a different net that floats right at the surface. If you have a flashlight, you can sweep it across the water, you see, and drive them towards the net. But they can be dangerous. Their nose is very sharp. When I was still strong, in the Philippines, a man was hit by one.’ He was laughing now, and the rest of the story had to wait until he could keep a straight face. ‘You see, he was fishing at night, and another canoe came close to him, and a long-tom ran straight at his boat. It stuck in his leg like a spear. He was so angry he took his parang and cut the long-tom up into little pieces and burnt it on the fire until it was only ashes. He walked with a limp after, but he had luck he was not sitting down or he would be dead.’ He laughed again. ‘You see, a dangerous fish, but good to eat.’

I kept Sarani company until the tide fell and he could complete his last chore of the day. He slipped into the water and I passed down the props to him. He wedged them under the gunwales with his foot. He changed into a dry sarong and chewed a last wad of betel while he pumped out the bilge. He settled down next to Minehanga. They exchanged mumbled words. I stayed on the bow a while longer, drinking in the peace and the solitude, the lights on the reef like floating stars, a road of moonlight across the water.

Watching the net come into view I sensed again the excitement I had felt as a boy pulling up a lobster pot in Donegal. My father would set them close in to Loughros Point and it would be my job to pull them up, while he kept us off the rocks. The pot would emerge like a coffer from the deep, shimmering, magnified, full maybe.

There was a long pull before the first fish appeared in the net, a glint of silver blue light from way below where the net’s parabola could last be seen, the pure white belly of a ray. More were following. Pilar gripped them by the eye sockets, which offered the only safe purchase on the streamlined body, and pulled them through the mesh of the net, throwing them into the corner between gunwale and splashboard, right below where I sat. I watched the heap grow, olive-brown ray with light blue spots flapping their wings on the deck. Some landed on their backs, mouths working, the gill vents opening and closing, seeming to sigh.

We netted fourteen in all, but Sarani was not happy. ‘Before, we could catch forty or fifty ray in one netting. Now, you see, how many tails? Kami rugi, ba. In the market we sell three tails for two ringgit (50p). This catch is less than ten ringgit. And how many ringgit of oil did we use? Going and returning putting down the net, going and returning pulling it up, maybe five ringgit over. And how much oil to go to Semporna to sell them? Kami rugi minyak, we are wasting oil. Also, you saw the holes in the net? I think there is a rat living in the hold.’

Most of our fishing trips ended this way, with Sarani complaining about the price of fish and the cost of diesel. The dwindling of the local fish stock was threatening their survival, and it was not just under attack from the fish-bombers. Sarani told me that they used to catch lobsters in their nets, but the ‘hookah’ fishermen had taken most of them. A weighted diver equipped only with the sort of goggles Sarani used and a nose clip goes down to the bottom breathing from a free-flowing air hose to collect them. I had read reports that they often stay at depths of 60–100 feet for as long as two hours and surface without decompression stops. The bends are a commonplace, known as bola-bola, ‘bubbles’. The method can also be used to catch desirable species of fish; the diver stuns them by releasing a cyanide poison into the water. They are sold to the ‘fish farms’ that lie in the channel between Semporna and Bum Bum. Often the ‘fish farm’ owns the boat and the compresser. They are not so much farms as way-stations. No breeding goes on. The fish are kept in pens until the cyanide has been purged from their system and then they are sent live to the Hong Kong markets.

The Bajau Laut cannot compete against these fishing methods. Sarani blamed them for the declining ray population, but the Bajau Laut themselves seemed the most likely culprits in that case. The Mabul fleet could not lay ten nets, say, catching forty ray daily for ten years and not have had an effect on the size of the stock. I had been watching the last gasps of a ray on our way back to Kapalai. It was on its back. Shivering sighs passed through its body. Its gulps for water became less frequent. Finally the muscles of its belly went slack, and a rush of fluid came from its cloaca, followed by a tiny, completely formed pup, its wings rolled over under its stomach like the curled-up sides of a tongue. It was alive, born mimicking its parent’s weakening death throes. I flicked it over the side; they are also born with a sting. Being viviparous makes the ray population extremely sensitive to the loss of mature adults.

We poled out to the edge of the reef and anchored so that we would not be caught by the falling tide when we wanted to leave Kapalai. We were joined by two other boats, Pilar’s and that belonging to Merikita. He had married Pilar’s elder sister, Timaraisa, and had become part of Sarani’s group. They had two sons and a daughter a little older than Arjan. Their boat was neat and painted in the same colours as the rest of the fleet, light blue and white and red-brown, no bigger than Sarani’s but roofed like Pilar’s. The roof showed that their recent outings had been more successful than ours. They had more than twenty fresh ray hung out on poles and twice that many already dried, tied into bunches. Timaraisa sat in the stern shelling a string bag full of clams with a parang. She scooped out the flesh into a bowl and then strung them up to dry. Merikita had already set off in his canoe to catch lunch. He had a stocky and powerful physique and a round face. He was shy and softly spoken. Sarani always referred to him as ‘Merikita, the fat one’, never just ‘Merikita’, but in a matter-of-fact way, without judgement, and often it was ‘Merikita, the fat one, rajin sekali, dia, he’s very hard-working. His children are not hungry.’ I never heard him pay a higher compliment. We weighed anchor in the afternoon, headed for Mabul where we would spend the night before moving on to Semporna in the morning.

There were more boats strung out over the shallows south of Mabul than there had been at Kapalai, and word went round that we were bound for Semporna. Canoes started to arrive and produce was loaded onto Pilar’s boat, ready for an early start. We would use his boat; not only was its engine more powerful, but also because it would no longer be afloat if left all day with no one to pump out the bilge. Timaraisa arrived with dried ray and clams on strings like bunches of keys. I sat with Sarani, making out a shopping list. We had not talked again about money since the first day when he suggested I pay him for a five-day tour of the islands. He knew more about me now, and it seemed, mercifully, he had forgotten his plan. I hoped that I had shown him that I wanted to help where I could, to join in their life. I would help with supplies if necessary, but the old aid-workers’ adage seemed particularly appropriate: ‘Give a person a fish, and you feed them for a day; give them a net and they can feed themselves for life.’ Over-simple, maybe – there have to be fish to catch in the first place – but, as Pilar took Sarani’s hurricane lamp to pieces and named the parts that needed replacing (Sarani was not so good with technology), I wrote them down on my list, happy in the knowledge that for a few ringgit I could double Sarani’s fishing opportunities on the reef. Fish-spear tips went onto the list. I added condoms. And delousing shampoo. And, Jayari reminded me when we went to visit, ‘if you pity me’, cough syrup. It was dark when we left his house. I had watched him sitting at the seaward door, smoking a Fate as the sun set, as I had when I had first landed on Mabul.

We weighed anchor in the first light, the sun just edging over the horizon as we passed the last stilt houses, and ran straight across the Creach Reef on the highest of the tide. Looking back at the island I little expected that this view would change overnight.

All the traffic of the coast was funnelled into the Semporna Channel, the port’s only approach from the south. Jongkong and pump-boats were putting out from the jetties of Bum Bum, from the creeks and estuaries of the mainland, filled with people bound for the market. We overhauled a commercial fishing boat, idling home along the coast from Tawau waters after a night netting squid by arc light. The crew were sorting the catch on the afterdeck. We left dug-outs bobbing in our wake, old men solemnly jigging handlines at the edge of the reef.

We made the last dog-leg into Semporna roads, the scattered villages on the mainland shore coalescing into the stilted suburbs south of the town. A jongkong from Bum Bum passed close by, a mixture of ages and sexes, all freshly scrubbed and ready for the mainland. The children were in school uniforms, red and white or blue and white depending on their grade. The men and women were smartly dressed too, the women in brightly patterned dresses, many of the men wearing the traditional Malay songkok velvet hat and the name badges of clerks and officials on fresh short-sleeved shirts. The Bajau Laut have their own caches of clean clothes. Above his dark shorts Sarani had put on a gingham shirt in the red-browns and pale yellows of Ralph Lauren’s Western palette. He looked very fetching; only the tear at the shoulder and his long white stubble let him down. I put razors on my list. The women looked comely in clean blouses and tight sarongs. Sumping Lasa wore a lacy dress and her hair in bunches. She was taking her flip-flops for a test drive, running to and fro through the cabin. There was very little clearance between her head and the roof beams; I did not want to be near when she grew that last millimetre. Arjan had been persuaded to wear his one shirt, grubby beyond measure, pseudo-Tom and Jerry characters in pink and yellow chasing across his back, the front held together, sometimes, with a safety-pin.

We passed the fish quay where the trawlers were unloading, the ramshackle drinks stalls and ice houses at the end of the mole, and on into the mêlée of craft milling around the margins of the water market, jongkong nipping in and out, disgorging their passengers, taking on cargo, pump-boats puttering around in between. We came in slowly, shouldering our way to a place at the mooring, and trading for our catch had started before the engine had been cut. A pump-boat from Bum Bum with a family aboard came up astern, and the matron in its bows started to bargain for fresh clams. We docked and before we had tied up, there was a man on the bow deck, picking over the shark-fin. Another shouted down, did we have any kahanga, and who’s the whitey? He climbed aboard to examine both. The women seemed to be in charge of selling the produce, so Sarani and I went to a café. We stepped up onto the walkway and were swallowed by the crowd.

The water village, the kampung air, is a particularly Malay phenomenon. Most coastal towns have one, in fact most coastal towns began life as a kampung air, a hamlet on stilts over tidal flats. It is a practical way for a coastal people to live. Your doorstep is the jetty to which you can tie up and from which you can launch whatever the state of the tide. Your house catches even the lightest sea breeze and living beyond the beach you are untroubled by the mosquitoes of the coast and the diseases they carry. You are ideally positioned should danger threaten from the land to escape to the sea, and vice versa. On land, the mosque nestles at the edge of the coconut groves; behind the palm belt are the well and the gardens. Sanitation and waste disposal are left to the care of the sea and its creatures. The system works just as well on rivers and in estuaries. Such is the Malay idyll, a life of simplicity, sufficiency and virtue, and such is its continuing power in the Malay imagination that ‘to go back to the kampung’ is a rustication much wished for by urban types. To be ‘just a kampung boy’ is certainly no barrier to high political office. Dr. Mahathir, the Prime Minister of Malaysia, was a kampung boy.

Leaving sewerage to nature is all well and good whilst the concentration of effluent-producers remains low. Garbage disposal is equally simple if the packaging is biodegradable – rattan and woven palm-frond baskets, banana leaves and coconut fibre string, containing foods clad in skins, scales, peels, rinds, husks, shells. Introduce plastic into the equation and trouble is not far away. As we shuffled with the crowd past dry-goods stalls, selling slabs of cassava sealed in plastic, sugar, rice and tea at pre-measured weights in plastic bags, the sweets and snacks, the pills and cigarettes, all wrapped in plastic, all waiting to be carried off in a black-blue-white-pink stripy plastic carrier bag, it depressed me to think that much of it would end up in the sea.

The café’s television was already on, loud. It was at the far end of the room, but where Sarani and I sat, at the back, near the door, was not a quiet spot. The sound was quadraphonic, the set vast; they were showing a beat-’em-up movie on laser disc player. To think that a lad from, say, Pulau Tiga, an island with two papaya trees and a volleyball net, could come to Semporna and watch phoney American kung-fu films on laser disc, in a kedai on stilts that felt as unsteady as a tree-house and shook every time a boy-porter trundled his blue wheelbarrow along the sun-lit walkway the other side of the wall from our table, toting jerrycans of fuel, sacks of salt, that I was sitting here watching extravagant fight scenes, more blows to the head than a skull could take, and the pugilists getting up to crack more ribs, to extract more gut-wrenched groans, in quadraphony, that I was watching with an old man who had two teeth and lived on the sea – I was in a state of culture shock for a moment.

A man in a songkok put his head round the door and greeted Sarani in Sama, ‘Magsukur, Panglima,’ shook his hand, touched his own to his heart. ‘Good morning,’ he said to me in English. He sat down at our table, and studied me carefully, my hair dirty and swept back by the wind like Sarani’s, four days of stubble and sun on my face. I did the polite thing and offered my food to the new arrival; he did the polite thing and refused. ‘Who is this, Panglima?’ The conversation went ahead in Sama, but words like ‘Italy’ popped out.

‘But what does the American eat?’ This I could understand, my first complete Sama sentence, ‘Melikan amanggan na ai?’

‘Pangi’ kayu,’ said Sarani.

‘Pangi’ kayu? Cassava?’ he said, glancing at the plate of fried rice in front of me.

‘Aho’,’ I said, ‘yes,’ a Sama word I could pronounce with confidence. It was a cheap trick, but it took him aback. Sarani was delighted.

‘You speak Sama?’

‘Belum, not yet,’ I had to admit, in Malay.

‘But he speaks good Malay,’ Sarani added, and I got the feeling he was a little proud of me. The man studied me a while longer. I slurped my iced coffee.

‘So what does he drink?’ – this in Sama again.

‘Bohé, water.’

‘And where does he sleep?’

‘On the boat.’

The man was silent as he looked at me, until his manners recalled him, and he nodded and smiled. I sat back in my chair – a chair! – the heat of the chilli still on my tongue, the cold milky coffee, the sweetness of a clove cigarette on my lips – and listened to no more of their conversation.

Sarani cracked a red-lipped grin at me after he had left. ‘You see, he was very surprised,’ and he laughed out loud. ‘Pangi’ kayu! He said he had never seen an orang putih like you before! Pangi’ kayu! Did you see how surprised he was when you said aho’?’ His old eyes creased up, his twin teeth like comic store vampire fangs, and it was the same wherever we went together, the surprise, the questions were the same. ‘Pangi’ kayu?!’ That seemed to surprise the interrogators above all and indeed I had come across this low opinion of cassava before. I cannot say that the prejudice against it is unjustified. Given the choice between a ball of steamed cassava flour and the plate of fried rice I had just put away, I know which I would prefer. Yet it is not just that cassava and that school canteen favourite, sago, are not as savoury as rice. They are both poor man’s food, and above all it is the fact that they are the staples of ‘primitive’ people, orang asli, the wild people of the woods who eat pig and monkey, haram foods. By association sago and cassava are considered uncivilised, un-Malay and un-Islamic.

Rice on the other hand, that gives twenty-fold, is revered. Throughout South East Asia, there are propitiatory rites to be observed at its planting, from the spilling of blood to the casting of spells. Its harvest is celebrated. Rice is the cornerstone of all South East Asian civilisation. Where there is wet-rice cultivation there are royal courts, god-kings, temple cities, art, and people. Java has three crops of rice a year from its rich volcanic soil. Its population density is 800 people per square kilometre. In Borneo, where there is one crop and cultivable land is confined to the coast, it is around twenty-five. That a white man from a culture they regarded as the acme of civilisation, a man of means, should eschew rice in favour of cassava was eccentric in the extreme. After a week of nothing else I wanted to spend a night in Semporna to redress the balance. Sarani came with me to the hotel.

We picked our way through the market towards the shore, shrugging off the attentions of the barrow boys, past the wet fish stalls, through the aroma of dried fish and the tunnels of second-hand clothes, past tailors cross-legged beside old Singers, hairdressers’ stalls where mincing transvestites primped, looking uncomfortable out of drag, past the Islamic paraphernalia booth, selling Korans and calendars and posters of the Ka’aba. The kampung has grown seawards through a process of accretion, the outer edges made of bright new timber, the walkways airy. The alleys of the older core closer to land were shadowy, the boards underfoot worn and patched, and below the sea had retreated to expose the stinking flats to the sun. We emerged at the back of the vegetable market next to the golden domes of the mosque.

For a Malay kampung to grow into a town, into a commercial centre, it relies on Chinese capital. This has been true of all South East Asia in the twentieth century; business has become concentrated in Chinese hands. Reactions to this trend have varied. In Malaysia the balance of economic power tilted so far towards the Chinese that there were race-riots in 1969. Town centres burned. The arsonists did not have to be particular about which businesses they torched; they were all Chinese-owned. We crossed the road, Sarani very wary of the cars, and shuffled through the narrow alley, past sellers of contraband cigarettes and lottery tickets, past Suluk money-changers waving wads of Filipino pesos, past the Chinese gold shop doing business through a gap in its steel shutters, and into the high street. The arsonist, or the pirate, would not have to be any more picky today in Semporna.

In my room Sarani plonked himself down on the bed and tried to bounce, but the dead mattress on the wooden box-frame gave nothing back. Still he said, ‘Good for playing love, eh?’ and chuckled. ‘By the way, don’t forget that medicine we talked about, that medicine for boys.’ Sarani tried out the bed some more, but became serious. ‘I must go. That man in the café, he told me his wife is calling me. She has pain in her leg. I must go to her now. After I will meet you here?’ I was intrigued.