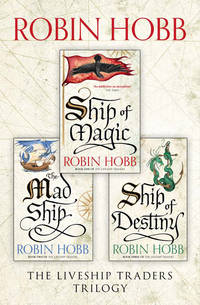

The Complete Liveship Traders Trilogy: Ship of Magic, The Mad Ship, Ship of Destiny

His first hint that she was aboard had not been the sight of her. He’d glimpsed her any number of times as ‘a ship’s boy’ and given no thought to it. Her flat cap pulled low on her brow and her boy’s clothes had been more than sufficient disguise. The first time he’d seen a rope secured to the hook on a block with a double blackwall hitch rather than a bowline, he’d raised an eyebrow. It was not that rare a knot, but the bowline was the common preference. Captain Vestrit, however, had always preferred the blackwall. Brashen hadn’t given much thought to it at the time. A day or so later, coming out on deck before his watch, he’d heard a familiar whistle from up in the rigging. He’d looked up to where she was waving at the lookout, trying to catch his attention for some message, and instantly recognized her. ‘Oh, Althea,’ he’d thought to himself calmly, and then started an instant later as his mind registered the information. In disbelief, he’d stared up at her, mouth half-agape. It was her: no mistaking her style of running along the footropes. She’d glanced down, and at sight of him had so swiftly averted her face that he knew she’d been expecting and dreading this moment.

He’d found an excuse to linger at the base of the mast until she came down. She’d passed him less than an arm’s length away, with only one pleading glance. He’d clenched his teeth and said nothing to her, nor had he spoken to her since then until tonight. Once he had recognized her, he’d known the dread of certainty. She wouldn’t survive the voyage. Day by day, he’d waited for her to somehow betray herself as a woman, or make the one small error that would let the sea take her life. It had seemed to him simply a matter of time. The best he had been able to hope for her was that her death would be swift.

Now it appeared that would not be the case. He allowed himself a small, rueful smile, The girl could scramble. Oh, she hadn’t the muscle to do the work she was given. Well, at least not as fast as the ship’s first mate expected such work to be done. It wasn’t, he reflected, so much a matter of muscle and weight that she lacked; she could do the work well enough, actually, save that the men she worked alongside overmatched her. Even a few inches of extra reach, a half-stone of extra weight to fling against a block-and-tackle’s task could make all the difference. She was like a horse teamed with oxen; it wasn’t that she was incapable of the work, only that she was mismatched.

Additionally, she had come from a liveship — her family liveship, at that — to one of mere wood. Had Althea even guessed that pitting one’s strength against dead wood could be so much harder than working a willing ship? Even if the Vivacia hadn’t been quickened in his years aboard her, Brashen had known from the very first time he touched a line of her that there was some underlying awareness there. The Vivacia was far from sailing herself, but it had always seemed to him that the stupid incidents that always occurred aboard other ships didn’t happen on her. On a tub like the Reaper, work stair-stepped. What looked like a simple job, replacing a hinge for instance, turned into a major effort once one had revealed that the faulty hinge had been set in wood that was half-rotten and out of alignment as well. Nothing, he sighed to himself, was ever simple on board the Reaper.

As if in answer to the thought, he heard the sharp rap of knuckles against his door. It wasn’t his watch so that could only mean trouble. ‘I’m up,’ he assured his caller. In an instant he was on his feet and had the door opened. But this was not the mate come to call him to extra duties on this stormy night. Instead Reller stepped in hesitantly. Water still streamed down his face and dripped from his hair.

‘Well?’ Brashen demanded.

A frown divided the man’s wide brow. ‘Shoulder’s paining me some,’ he offered.

Brashen’s duties included minding the ship’s medical supplies. They’d started the voyage with a ship’s doctor he’d been told, but had lost him overboard one wild night. Once it had been discovered that Brashen could read the spidery letters that labelled the various bottles and boxes of medicines, he’d been put in charge of what remained of the medical stores. He personally doubted the efficacy of many of them, but passed them out according to the labels’ instructions.

So now he turned to the locked chest that occupied almost as much space as his own sea-chest did and groped inside his shirt for the key that hung about his neck. He unlocked the chest, frowned into it for a moment, and then took out a brown bottle with a fanciful green label on it. He squinted at the writing in the lantern’s unsteady light. ‘I think this is what I gave you last time,’ he guessed aloud, and held the bottle up for Reller’s inspection.

The sailor peered at it as if a long stare would make the letters intelligible to him. At last he shrugged. ‘Label was green like that,’ he allowed. ‘That’s probably it.’

Brashen worked the fat cork loose from the thick neck and shook out onto his palm half a dozen greenish pellets. They looked, he thought to himself, rather like a deer’s droppings. He’d have only been mildly surprised to discover that’s what they actually were. He returned three to the bottle and offered the other three to Reller. ‘Take them all. Tell Cook I said to give you a half-measure of rum to wash those down, and to let you sit in the galley and stay warm until they start working.’

The man’s face brightened immediately. Captain Sichel was not free with the spirits aboard ship. It would probably be the first taste he’d had since they’d left Bingtown. The prospect of a drink, and a warm place to sit for a time made the man’s face glow with gratitude. Brashen knew a moment’s doubt but then reflected that he had no idea how well the pellets would work; at least he could be sure that the rough rum they bought for the crew would help the man to sleep past his pain.

As Reller was turning to leave, Brashen forced himself to ask his question. ‘My cousin’s boy… the one I asked you to keep an eye on. How’s he working out?’

Reller shrugged. He jiggled the three pellets loosely in his left hand. ‘Oh, he’s doing fine, sir, just fine. He’s a willing lad.’ He set his hand to the latch, clearly eager to be gone. The promised rum was beckoning him.

‘So,’ Brashen went on in spite of himself. ‘He knows his job and does it smartly?’

‘Oh, that he does, that he does, sir. A good lad, as I said. I’ll keep an eye on Athel and see he comes to no harm.’

‘Good. Good, then. My cousin will be proud of him.’ He hesitated. ‘Mind, now, don’t let the boy know any of this. Don’t want him to think he’ll get any special treatment.’

‘Yes sir. No sir. Goodnight, sir.’ And Reller was gone, shutting the door firmly behind him.

Brashen shut his eyes and took a deep breath. It was as much as he could do for Althea, asking a reliable man like Reller to keep an eye on her. He checked to make sure the catch on his door was secure, and then re-locked the cabinet that held the medical supplies. He crawled back into the narrow confines of his bunk and heaved a heavy sigh. It was as much as he could do for Althea. Truly, it was. It was.

Eventually, he was able to fall asleep.

Wintrow didn’t like the rigging. He had done his best to conceal that from Torg, but the man had a bully’s unerring instinct. As a result, a dozen times a day he would fabricate a reason why Wintrow had to climb the mast. When he had sensed the repetition was dulling Wintrow’s trepidation, he had added to the task, giving him things to carry aloft and place in the crow’s nest, only to send him to fetch them back down almost as soon as he’d regained the deck. Torg’s latest commands had him not only climbing the rigging, but going out to the ends of the spars and clinging there, heart in his mouth, waiting for Torg’s shouted command to return. It was simple hazing, of the stupidest, most predictable sort. Wintrow expected such from Torg. It had been harder to comprehend that the rest of the crew accepted his torment as normal. When they paid any attention at all to what Torg was subjecting him to, it was usually with amusement. No one intervened.

And yet, Wintrow reflected as he clung to a spar and looked down at the deck so far below him, the man had actually done him a favour. The wind rushed past him, the canvas was full-bellied with it, and the line he perched on sang with the tension. The height of the mast exaggerated the ship’s motion through the water, amplifying every roll into an arc. He still did not like being up there, but he could not deny there was an exhilaration to being there that had nothing to do with enjoyment. He had met a challenge and bested it. Left to himself, he would never have sought to take his own measure in this way. He squinted his eyes to the wind that rushed past his ears deafeningly. For a moment he toyed with the idea that perhaps he did belong here, that maybe deep within the priest there could be the heart of a sailor.

A small, odd noise came to his ears. A vibration of metal. He wondered if it were some fitting about to give way, and his heart began to beat a bit faster. Slowly he worked his way along the ratline, looking for the source of the sound. The wind mocked him, bringing the sound and then blasting it away. He had heard it a few times before he recognized that there were variations in tone and a rhythm to the sound that defied the steady rush of the wind. He got to the crow’s nest and clung to the side.

Within the lookout’s post was Mild. The sailor had folded himself up into a comfortable braced squat. His eyes were closed to slits, a tiny jaw harp braced against his cheek. He played it one-handed, the sailor’s way, using his own mouth as a sounding box as his fingers danced on the metal prongs that were the keys. His ears were turned to his private music as his eyes scanned the horizon.

Wintrow thought he was unaware of him until the other boy’s eyes darted briefly to his. His fingers stilled. ‘What?’ he demanded, not taking the instrument from the side of his face.

‘Nothing. You on watch?’

‘Sort of. Not much to watch for.’

‘Pirates?’ Wintrow ventured.

Mild snorted. ‘They don’t bother a liveship, usually. Oh, I’ve heard rumours from when we were in Chalced, that one or two got chased, but for the most part they leave us alone. Most liveships can outrun any wooden ship under identical conditions, unless the liveship has a really carp crew. And the pirates know that even if you catch up with a liveship, you’re in for the fight of your life. And even if they win, what do they have? A ship that won’t sail for them. I mean, do you think Vivacia would welcome strangers aboard her and accept them running her? Not much!’

‘Not much,’ Wintrow agreed. He was pleasantly surprised — both by Mild’s obvious affection and pride for the ship, and by the boy’s conversation with him. Mild seemed flattered by the boy’s rapt attention, for he narrowed his eyes knowingly and went on, ‘The way I see it, right now the pirates are doing us a big favour.’

Wintrow bit. ‘How?’

‘Well. How to explain it… you didn’t get ashore in Chalced, did you? Well, what we heard there was that pirates were suddenly attacking some of the slavers. At least one taken, and rumours of others being threatened. Well. It’s end of autumn now, but by spring, Chalced needs a powerful lot of slaves to do the spring ploughing and planting. If pirates are picking off the regular slavers, well, by the time we run into Chalced with a prime load, it will be a seller’s market. We’ll get so much for our haul, we can probably go straight home to Bingtown.’

Mild grinned and nodded in satisfaction, as if somehow Kyle getting a good price for slaves would reflect well on him. He was likely only repeating what he’d heard the elders of the crew say. Wintrow said nothing. He looked far out over the heaving water. There was a heavy, sick place under his heart that had nothing to do with sea-sickness. Whenever he thought forward to Jamaillia and the actual act of his father buying slaves to sell, a terrible sorrow welled up in him. It was like having the guilt and pain of a shameful memory in advance of the event. After a moment, Mild picked up the conversation again.

‘So. Torg’s got you up here again?’

‘Yeah.’ Wintrow surprised himself, stretching his shoulders and then leaning back casually against his grip. ‘Doesn’t bother me so much any more.’

‘I can tell. That’s why they do it.’ When Wintrow lifted his brows, Mild grinned at him. ‘Oh, you thought it was a special torture just for you? No. Torg likes picking on you. Sa’s balls, Torg likes picking on anyone. Anyone he can get away with, anyway. But running the ship’s boy up and down the mast is a tradition. When I first come aboard, I hated it. Brashen was mate then, and I thought he was the son of a sow. Once he realized I was nervous about coming up here, he saw to it that every one of my meals ended up here. “You want to eat, go get it,” he’d tell me. And I’d have to climb the mast and crawl around up here until I found a bucket with my mess in it. Damn, I hated him. I was so scared and slow, my food was almost always cold when I found it, and half the time there’d be rain sloshing around with it. But I learned, same as you, not to mind it after a while.’

Wintrow was silent, thinking. Mild’s fingers danced again over the keys, picking out a lively little tune. ‘Then Torg doesn’t hate me? This is some kind of training?’

Mild stopped with a snort of amusement. ‘Oh, no. Depend on it. Torg hates you. Torg hates everyone that he thinks is smarter than he is, and that’s most of us aboard. But he knows his job, too. And he knows that if he wants to keep it, he’s got to make you into a sailor. So, he’ll teach you. He’ll make it as painful and unpleasant as he can, but he’ll teach you.’

‘If he’s such a hateful person, why does my… the captain keep him on as second mate?’

Mild shrugged. ‘Ask your Da,’ he said cruelly. Then he grinned, almost making that a joke. He went on, ‘I hear that Torg had been with him quite a while, and stuck with him on a real bad trip on the ship they used to be on. So when he came to the Vivacia, he brought Torg with him. Maybe no one else would hire him and he felt an obligation. Or maybe Torg’s got a nice tight arse.’

Wintrow’s jaw went slack at the implication. But Mild was grinning again. ‘Hey, don’t take it so serious. No wonder everyone loves to tease you, you’re such a mark.’

‘But he’s my father,’ Wintrow protested.

‘Naw. Not when you’re serving aboard his ship. Then he’s just your captain. And he’s an okay captain, not as good as Ephron was, and some of us still think Brashen should have took over when Cap’n Vestrit stepped off. But he’s okay.’

‘Then why did you say… that about him?’ Wintrow was genuinely mystified.

‘Because he’s the captain,’ Mild laboriously explained. ‘Sailors always say and do like that, even if you like the man. Because you know he can shit on you any time he wants. Hey. You want to know something? When we first found out that Cap’n Vestrit was getting off and putting a new man on, you know what Comfrey done?’

‘What?’

‘He went to the galley and took the cap’n’s coffee mug and wiped the inside with his dick!’ Delight shone in Mild’s grey eyes. He waited in anticipation for Wintrow’s reaction.

‘You’re teasing me again!’ A horrified smile dawned on his face despite himself. It was disgusting, and degrading. It was too outrageous to be true, for a man to do that to another man he hadn’t even met yet, just because that man would have power over him. It was unbelievable. And yet… and yet… it was funny. Suddenly Wintrow grasped something. To do that to a man you knew would be cruel and vicious. But to do that to an unknown captain, to be able to look up at the man who had life and death power over you and imagine him drinking the taste of your dick with his coffee… He looked aside from Mild, feeling with disbelief the broad grin on his face. Comfrey had done that to his father.

‘Crew’s gotta do a few things to the cap’n, and the mate. Can’t let them get away with always thinking they’re gods and we’re dung.’

‘Then… you think they know about stuff like that?’

Mild grinned. ‘Can’t be around the fleet too long and not know it goes on.’ He twanged a few more notes, then shrugged elaborately. ‘They probably just think it never happens to them.’

‘Then no one ever tells them,’ Wintrow clarified for himself.

‘Of course not. Who’d tell?’ A few notes later, Mild stopped abruptly. ‘You wouldn’t, would you? I mean, even if he is your Da and all…’ His voice trailed off as he realized that he might have been very indiscreet.

‘No, I wouldn’t tell,’ Wintrow heard himself say. He found a foolish grin on his face as he added wickedly, ‘But mostly because he is my father.’

‘Boy? Boy, get your arse down here!’ It was Torg’s voice, bellowing up from the deck.

Wintrow sighed. ‘I swear, the man can sense when I’m not miserable, and always takes steps to correct it.’

Wintrow began the long climb down. Mild leaned over slightly to watch his descent and called after him, ‘You use too many words. Just say he’s on your arse like a coat of paint.’

‘That, too,’ Wintrow agreed.

‘Move it, boy!’ Torg bellowed again, and Wintrow gave all his attention to scrambling down.

Much later that night, as he meditated in forgiveness of the day, he wondered at himself. Had not he laughed at cruelty, had not his smile condoned the degradation of another human being? Where was Sa in that? Guilt washed over him. He forced it aside; a true priest of Sa had little use for guilt. It but obscured; if something made a man feel bad then he must determine what about it troubled him, and eliminate that. Simply to suffer the discomforts of guilt did not indicate a man had improved himself, only that he suspected he harboured a fault. He lay still in the darkness and pondered what had made him smile and why. And for the first time in many years, he wondered if his conscience were not too tender, if it had not become a barrier between him and his fellows. ‘That which separates is not of Sa,’ he said softly to himself. But he fell asleep before he could remember the source for the quote, or even if it were from scripture at all.

Their first sighting of the Barrens came on a clear cold morning. The voyage northeast had carried them from autumn to winter, from mild blue weather to perpetual drizzle and fog. The Barrens crouched low on the horizon. They were visible not as proper islands, but only as a place where the waves suddenly became white foam and spume. The islands were low and flat, little more than a series of rocky beaches and sand plains that chanced to be above the high tide line. Inland, Althea had heard there was sand and scrubby vegetation and little more than that. Why the sea-bears chose to haul out there, to fight and mate and raise their young, she had no idea. Especially as each year at this time, the slaughter boats came to drive and kill hundreds of their kind. She squinted her eyes against the flying salt spray and wondered what kind of deadly instinct brought them back here every year despite their memories of blood and death.

The Reaper came into the lee of the cluster of islands at about noon, only to find that one of their rivals had already claimed the best anchorage. Captain Sichel cursed at that, cursed as if it were somehow the fault of his men and his ship that the Karlay had beaten them here. Anchors were set and the hunters roused from their stupor of inactivity. Althea had heard that they’d quarrelled over their gambling a few days ago and all but killed one of their number who they’d suspected of cheating. It was nothing to her; they were foul-mouthed and ill-tempered on the occasions when she’d had to fetch for them in her duties as ship’s boy. She was not at all surprised they were turning on one another in their close quarters and idleness. And what they did to one another was no concern to her at all.

Or so she had thought. It was when they were safely anchored and she was looking forward to the first day of comparative quiet that they’d had in weeks that she suddenly discovered that it would affect her. Officially, she was off-duty. Most of her watch were sleeping, but she had decided to take advantage of the light and the relatively quiet weather to mend some of her clothes. Doing close work by lanternlight had begun to bother her eyes of late, to say nothing of the close air below decks. She’d found a quiet corner, in the lee of the house. She was out of the wind and the sun had miraculously found them despite the edge of winter in the air. She had just begun to cut squares of canvas from her worst worn pair of trousers to patch the others when she heard the mate bellow her name.

‘Athel!’ he roared, and she leapt to her feet.

‘Here, sir!’ she cried, heedless of the work that had spilled from her lap.

‘Get ready to go ashore. You’ll be helping the skinners; they’re short a man. Lively, now.’

‘Yessir,’ she replied, as it was the only possible reply, but her heart sank. That did not slow her feet, however. She snatched up her work and carried it down the hatch with her, and set it aside to finish on some unforeseeable tomorrow. She jammed her calloused feet into felted stockings and heavy boots. The barnacled rocks would not be kind to bare feet. She snugged her knit cap more closely about her ears and dashed back up the steps to the deck. She was not a moment too soon, for the boats were already being raised by the davits. She lunged into one and took a place at an oar.

The sailors manned the oars while the hunters hunched their shoulders to the spray and icy wind and grinned at one another in anticipation. Favourite bows were gripped and held well out of the water’s reach, while oiled bags of arrows rolled sluggishly in the shallow bilge water of the skiff. Althea leaned hard on her oar, trying to match her companion. The boats of the Reaper moved together toward the rocky shores of the islands, each with a complement of hunters, skinners and sailors. She noticed, almost in passing, that Brashen pulled at the oars in one of the other boats. He’d be in charge of the sailors ashore then, she decided. She resolved to give him no reason to notice her. She’d be working with the hunters and skinners anyway; there was no need for their paths to cross. For an instant she wondered just what her task would be, then shrugged it off as useless curiosity. They’d tell her, soon enough.

Just as the rival ship had taken the best anchorage, so too her hunters had taken the prime island. By tradition the ships would not encroach on one another’s hunting territories. Past experience had taught them all that it led only to dead men and less profit for all. So the island where they put ashore was bare of all other human life. The rocky beaches were deserted, save for some very old sows resting in the shallows. The adult males had already left, beginning the migration back to wherever these creatures wintered. On the sandy inland plains, Althea knew they would find the younger females and this year’s crop of offspring. They would have lingered there, feeding off the late runs of fish and gathering fat and strength before they began their long journey.

The hunters and skinners remained in the boats when the rowers jumped overboard into the shallows and seized the gunwales of the skiffs to run the boats ashore. They timed this action to coincide with a wave to help them lift the boat clear of the sharp rocks. Althea waded out on the beach with the others, her soaked legs and wet boots seeming to draw in the cold.

Once ashore, she quickly found her duties, which seemed to be to do whatever the hunters and skinners didn’t care to do for themselves. She was soon burdened with all the extra bows, arrows, knives and sharpening stones. She followed the hunters inland with her arms heavily laden. It surprised her that the hunters and skinners walked so swiftly and talked so freely amongst themselves. She would have supposed this hunt to require some kind of stalking and stealth.

Instead, at the top of the first rise, the gently rolling interior of the island was revealed to her. The sea-bears sprawled and slept in clusters on the sand and amongst the scrub brush. As the men crested the hill, the fat creatures scarcely deigned to notice them. Those that did open their eyes regarded their approach with as little interest as they took in the dung-picker birds that shared their territory.