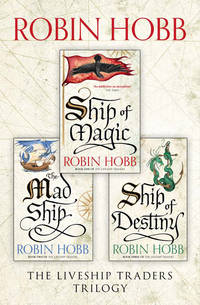

The Complete Liveship Traders Trilogy: Ship of Magic, The Mad Ship, Ship of Destiny

The hunters chose their positions. She was speedily relieved of the bags of arrows she had carried for them. She stood well back of them as they strung their bows and selected their targets. Then the deadly rain of arrows began. The animals they struck bellowed and some galloped awkwardly in circles before they died, but the creatures did not appear to associate their pain and deaths with the men upon the rise above them. It was almost a leisurely slaughter, as the hunters chose target after target and sent arrows winging. The throats were the chosen targets, where the broad-headed arrows opened the veins. Blood spilled thick. That was the death they meted out, that animals might bleed to death. This left the supple furs of their hides intact, as well as yielding meat that was not too heavy with blood. Death was not swift, nor painless. Althea had never seen much of meat-slaughter, let alone killing on such a scale. It repulsed her, and yet she stood and watched, as she was sure a true youth would have done, and tried not to let her revulsion show on her face.

The hunters were businesslike about their killing. As soon as the final arrows were expended, they moved down to reclaim them from the dead beasts, while the skinners came behind them like gorecrows to a battle scene. The bulk of the live animals had moved off in annoyance from the struggles and bellows of those struck and dying. They still seemed to feel no panic, only a distaste for the odd antics that had disturbed their rest. The leader of the hunters glanced at Althea in some annoyance. ‘See what’s keeping them with the salt,’ he barked at her, as if she had known she would have this duty and had neglected it. She scrambled to this command, just as glad to leave the scene of slaughter. The skinners were already at work, stripping the hide from each beast, salvaging tongues, hearts and livers before rolling the entrails out of the way and leaving the naked fat-and-meat creatures on their own hides. The knowledgeable gulls were already coming to the feast.

She had scarcely crested the rise before she saw a sailor coming toward her, rolling a cask of salt ahead of him. Behind him came a line of others, and she suddenly realized the scope of their task. Cask after cask of salt was making its way up the rise, while a raft of empty barrels was being brought ashore by yet another crew of sailors. All over the island, this was happening. The Reaper herself was securely anchored with no more than a skeleton crew aboard to maintain her. All the others had been pushed into the vast task of off-loading and ferrying kegs of salt and empty barrels ashore. And all, she realized, must then be transported back, the barrels heavy with salted meat or hides. Here they would stay to continue this harvest for as long as animals and empty barrels remained.

‘They want the salt now,’ she told the sailor pushing the first keg. He didn’t even bother to reply. She turned and ran back to her party of hunters. The hunters were already raining death down on another wing of the vast herd, while the skinners seemed to have finished fully half of what the hunters had already brought down.

It was the beginning of one of the seemingly endless bloody days that followed. To Althea fell the tasks that everyone else judged themselves too busy to do. She ferried hearts and tongues to a central cask, salting each organ as she added it to the barrel. Her clothes grew sticky and stiff with blood, dyed brown with repeated staining, but that was no different for anyone else. The erstwhile sailors who had been the debtors of Jamaillia were swiftly taught to be butchers. The slabs of yellowish fat were sliced clean of the meat and packed into clean barrels to be ferried back to the ship. Then the carcasses were boned out to conserve space in the barrels, the slabs of dark red meat were well-salted before they were laid down, and then over all a clean layer of salt before the casks were sealed. Hides were scraped clean of any clinging fat or red strips of flesh the skinners might have left, and then spread out with a thick layer of salt on the skin side. After a day of drying thus, they were shaken clean of salt, rolled and tied, and taken to the ship in bundles. As the teams of butchers moved slowly forwards, they left red-streaked bones and piles of gut-sacks in their wake. The sea-birds descended to this feast, adding their voices to those of the killers and the cries of those being killed.

Althea had hoped that she might gain some immunity to their bloody work, but with each passing day, it seemed to grow both more monstrous and more commonplace. She tried to grasp that this widespread slaughter of animals went on year after year, but could not. Not even the tangles of white bones on the killing fields could convince her that last year had seen slaughter on the same scale. She gave over thinking about it, and simply did her tasks.

They built a rough camp on the island, on the same site as last year’s camp, in the lee of a rock formation known as the Dragon. Their tent was little more than canvas stretched to break the wind and fires for warmth and cooking, but at least it was shelter. The sweet, heavy smells of blood and butchery still rode the wind that assailed them, but it was a change from the close quarters of the ship. The men built smoky fires with the resinous branches of the scrub brush that grew on the island and the scarce bits of driftwood that had washed up. They cooked the sea-bears’ livers over them, and she joined in the feasting, as glad as anyone over the change in their diet and the chance to eat fresh meat again.

In some ways, she was glad of her change in status. She worked for the hunters and skinners now, and her tasks were separate from those of the rest of the crew. She envied no one the heavy work of rolling the filled kegs back up the rise, over the rocky beach and then ferrying them back to the ship and hoisting them aboard and stowing them. It was mindless, back-breaking work. Drudgery such as that had little to do with sailing, yet no one of the Reaper’s crew was excused from it. Her own tasks continued to evolve as the hunters and skinners thought of them. She honed knives. She retrieved arrows. She salted and packed hearts and tongues. She spread hides and salted hides and shook hides and rolled hides and tied hides. She coated slabs of meat with salt and layered it into casks. The frequent exchange of blood and salt on her hands would have cracked them had not they been constantly coated with thick animal fat as well.

The weather had held fine for them, blustery and cold but with no sign of the drenching rains that could ruin both hides and meat. Then came an afternoon when the clouds suddenly seemed to boil into the sky, beginning at the horizon and rapidly encroaching on the blue. The wind honed itself sharper. Yet the hunters still killed, scarcely sparing a glance at the clouds building up on the horizon, tall and black as mountains. It was only when the first sleet began to arrow down that they gave over their own deadly rain and began shouting angrily for the skinners and packers to make haste, make haste before meat and fat and hides were lost. Althea scarcely saw what anyone could do to defy the storm, but she learned swiftly. The stripped hides were rolled up with a thick layer of salt inside them. All were suddenly pressed into work as skinners, butchers and packers. She abruptly found herself with a skinning knife in her hands, bent over a carcass still warm, drawing the blade from the sea-bear’s gullet to its vent.

She had seen it done often enough now that she had lost most of her squeamishness. Still, a moment’s disgust uncoiled inside her as she peeled the soft hide back from the thick layer of fat. The animal was warm and flaccid beneath her hands, and that first opening of its body released a waft of death and offal. She steeled herself. The wide, flat blade of her skinning knife slipped easily between fat and skin, slicing it free of the body while her free hand kept a steady tug of tension upon the soft fur. She holed the hide twice on her first effort, trying to go too fast. But when she relaxed and did not think about what she was doing so much as how to do it well, the next hide came free as simply as if she were peeling a Jamaillian orange. It was, she realized, simply a matter of thinking how an animal was made, where hide would be thick or thin, fat present or absent.

By her fourth animal, she understood that it was not only easy for her, but that she was good at it. She moved swiftly from carcass to carcass, suddenly uncaring of the blood and smell. The long slice to open the beast, the swift skinning, followed by a quick disembowelling. Heart and liver were freed with two slashes and the rest of the gut-sack rolled free of the body and hide. The tongue, she found, was the most bothersome, prying open the animal’s mouth and reaching within to grasp the still-warm, wet tongue and then hew it off at the base. Had it not been such a valuable delicacy she might have been tempted to skip it entirely.

At some point she lifted her head, to peer around her through the driving sleet. The cold rain pounded her back and dripped into her eyes, but until that moment of respite, she had been almost unaware of it. Behind her, she realized, were no less than three teams of butchers trying to keep up with her. She had left behind her a wide trail of stripped carcasses. In the distance, one of the hunters appeared to be speaking to the mate about something. He made an off-hand gesture towards her and she suddenly knew with certainty that she was the topic of their conversation. She once more bent her head to her work, her hands flying as she blinked away the cold rain that ran into her eyes and dripped from her nose. A small fire of pride began to burn within her. It was dirty, disgusting work, carried out on a scale that was beyond greed. But she was good at it. And it had been so long since she had been able to claim that for herself, her hunger for it shocked her.

There came a time when she looked around her and found no more animals to skin. She stood slowly, rolling the ache from her shoulders. She cleaned her knife on her bloody trousers, and then held her hands out to the rain, letting the icy water flush the blood and gobbets of fat and flesh from them. She wiped them a bit cleaner on her shirt and then pushed the wet hair back from her eyes. Behind her, men bent to work over the flayed carcasses in her wake. A man rolled a cask of salt toward her, while another followed with an empty hogshead. When a man stopped beside her and righted the cask, he lifted his eyes to meet hers. It was Brashen. She grinned at him. ‘Pretty good, eh?’

He wiped rain from his own face and then observed quietly, ‘Were I you, I’d do as little as possible to call attention to myself. Your disguise won’t withstand a close scrutiny.’

His rebuke irritated her. ‘Maybe if I get good enough at this, I won’t need to be disguised any more.’

The look that passed over his face was both incredulous and horrified. He stove in the end of the salt-cask, and then gestured at her as if he were bidding her get to work salting hides. But what he said was, ‘Did these two-legged animals you crew with suspect for one moment that you were a woman, they’d use you, one and all, with less concern than they give to this slaughter. Valuable as you might be to them as a skinner, they’d see no reason why they couldn’t use you as a whore as well. And they would see it that by your being here you had expected and consented to such use.’

Something in his low earnest voice chilled her beyond the rain’s touch. There was such certainty in his tone she could not imagine arguing with it. Instead she hurried off to meet the man with the hogshead, bearing with her the tongue and heart from her final beast. She continued with this task, keeping her head low as if to keep rain from her eyes and trying to think of nothing, nothing. If she had stopped to think of how easy that had become lately, it might have frightened her.

That evening when she returned to camp, she understood for the first time the naming of the rock. A trick of the last light slanting through the overcast illuminated the Dragon in awful detail. She had not seen it before because she had not expected it to be sprawled on its back, forelegs clutching at its black chest, outflung wings submerged in earth. The contortions of its immense body adumbrated an agonized death. Althea halted on the slight rise that offered her this view and stared in horror. Who would carve such a thing, and why on earth did they camp in its lee? The light changed, only slightly, but suddenly the eroded rock upthrust through the thin soil was no more than an oddly shaped boulder, its lines vaguely suggestive of a sprawled animal. Althea let out her pent breath.

‘Bit unnerving the first time you catch it, eh?’ Reller asked at her elbow.

She started at his voice. ‘Bit,’ she admitted, then shrugged her shoulders in boyish bravado. ‘But for all that, it’s just a rock.’

Reller lowered his voice. ‘You so sure of that? You ought to climb up on its chest some time, and take a look. That part there, that looks like forelegs… they clutch at the stump of an arrow shaft, or what’s left of one. No, boy, that’s the real carcass of a live dragon, brought down when the world was younger’n an egg, and rotting slow ever since.’

‘No such things as dragons,’ Althea scoffed at his hazing.

‘No? Don’t be telling me that, nor any other sailor was off the Six Duchies coast a few years back. I saw dragons, and not just one or two. Whole phalanx of ’em, flying like geese, in every bright colour and shape you can name. And not just once, but twice. There’s some as say they brought the serpents, but that ain’t true. I’d seen serpents years before that, way down south. Course, nowadays, we see a lot more of ’em, so folk believe in ’em. But when you’ve sailed as long as I, and been as far as I, you’ll learn that there’s a lot of things that are real but only a few folk have seen ’em.’

Althea gave him a sceptical grin. ‘Yeah, Reller, pull my other leg, it’s got bells on,’ she retorted.

‘Damned pup!’ the man replied in apparently genuine affront. ‘Thinks cause he can slide a skinning knife he can talk back to his betters.’ He stalked off down the rise.

Althea followed him more slowly. She told herself she should have acted more gullible; after all, she was supposed to be a fourteen year old out on his first lengthy voyage. She shouldn’t spoil Reller’s fun, if she wanted to keep on his good side. Well, the next time he trotted out a sea-tale, she’d be more receptive and make it up to him. After all, he was as close as she had to a friend aboard the Reaper.

Vivacia made her fourth port on a late autumn evening. The light was slanting across the sky, breaking through a bank of clouds to fall on the town below. Wintrow was on the foredeck, spending his mandatory evening hour with Vivacia. He leaned on the railing beside her and stared at the white-spired town snugged in the crook of the tiny harbour. He had been silent, as he often was, but lately the silence had been more companionable than miserable. She blessed Mild with all her heart. Since he had extended his friendship to Wintrow the boy had begun to thrive.

Wintrow, if not cheerful, was at least gaining a bit of the cockiness that was expected of a ship’s boy. When that post had been Mild’s, he had been daring and lively, into mischief when he was not being the ship’s jester for anyone who had a spare moment to share with him. When Mild had acquired the status of hand, he had settled into a more sober attitude toward his work, as was right. But Wintrow had suffered badly in comparison. It had showed all too plainly that his heart was not in his work. He had ignored or misunderstood the sailor’s attempts to jest with him, and his doldrums spirits had not been conducive to anyone wishing to spend time with him. Now that he was beginning to smile, if only occasionally, and to good-naturedly rebut some of the sailors’ jests, he was beginning to be accepted. They were more prone now to give the word of advice or warning that prevented him from making mistakes that multiplied his workload. He built on each small success, mastering his tasks with the rapidity of a mind trained to learn well. An occasional word of praise or camaraderie was beginning to waken in him a sense of being part of the crew. Some now perceived that his gentle nature and thoughtful ways were not a weakness. Vivacia was beginning to have hopes for him.

She glanced back at him. His black hair was pulling free of his queue and falling into his eyes. With a pang, she saw a ghost there, an echo of Ephron Vestrit when he had been that age. She twisted and reached a hand to him. ‘Put your hand in mine,’ she told him quietly, and for a wonder he obeyed her. She knew he still had a basic distrust of her, that he was not sure if she was of Sa or not. But when he put his own newly-calloused hand into hers, she closed her immense fingers around his, and they were suddenly one.

He looked through his grandfather’s eyes. Ephron had loved this harbour and this island’s folk. The shining white spires and domes of their city were all the more surprising given the smallness of their settlement. Back beneath the green eaves of the forest were where most of the Caymara folk lived. Their homes were small and green and humble. They tilled no fields, broke no ground, but were hunters and gatherers one and all. No cobbled roads led out of the town, only winding paths suitable for foot-traffic and hand-carts. They might have seemed a primitive folk, save for their tiny city on Claw Island. Here every engineering instinct was given vent and expression. There were no more than thirty buildings there, not including the profusion of stalls that lined their market street and the rough wooden buildings that fronted the waterfront for commercial trade. But every one of the buildings that comprised the white heart of the city was a marvel of architecture and sculpting. His grandfather had always allowed himself time to stroll through the city’s marble heart and look up at the carved faces of heroes, the friezes of legends, and the arches on which plants both lived and carved, climbed and coiled.

‘And you brought it here, much of the marble facing. Without you and him… oh, I see. It is almost like my windows. Light shines through them to illuminate the labour of my hands. Through your work, Sa’s light shines in this beauty…’

He was breathing the words, a sub-vocal whisper she could barely hear. Yet more mystifying than his words were the feelings he shared with her. A moving toward unity that he seemed to value above all else was what he appreciated here. He did not see the elaborately-carved façades of the buildings as works of art to enjoy. Instead, they were an expression of something she could not grasp, a coming together of ship and merchant and trading folk that had resulted not just in physical beauty but… arcforia-Sa. She did not know the word, she could only reach after the concept. Joy embodied… the best of men and nature coming together in a permanent expression… justification of all Sa had bequeathed so lavishly upon the world. She felt a soaring euphoria in him she had never experienced in any of his other kin, and suddenly recognized that this was what he missed so hungrily. The priests had taught him to see the world with these eyes, had gently awakened in him a hunger for unadulterated beauty and goodness. He believed his destiny was to pursue goodness, to find and exult it in all its forms. To believe in goodness.

She had sought to share and teach. Instead, she had been given and taught. She surprised herself by drawing back from him, breaking the fullness of the contact she had sought. This was a thing she needed to consider, and perhaps she needed to be alone to consider it fully. And in that thought she recognized yet again the full impact Wintrow was having on her.

He was given shore-time. He knew it did not come from his father, nor from Torg. His father had gone ashore hours ago, to begin the negotiations for trade. He had taken Torg with him. So the decision to grant him shore-time with the others seemed to come from Gantry, the first mate. It puzzled Wintrow. He knew the mate had full charge of all the men on board the ship, and that only the captain’s word was higher. Yet he did not think Gantry had even been fully cognizant of his existence. The man had scarcely spoken to him directly in all the time he had been aboard. Yet his name was called out for the first group of men allowed time ashore, and he found his heart soaring with anticipation. It was too good a piece of luck to question. Each time they had anchored or docked in Chalced, he had stared longingly at the shore, but had never been allowed to leave the ship. The thought of solid ground underfoot, of looking at something he had not seen before was ecstatically dizzying. Like the others fortunate enough to be in the first party he dashed below, to don his shore-clothes and run a brush through his hair and re-plait his queue. Clothes gave him one moment of indecision.

Torg had been given charge of purchasing Wintrow’s kit before they left Bingtown. His father had not trusted Wintrow with money and time in which to buy the clothes and supplies he would need for the voyage. Wintrow had found himself with two suits of canvas shirts and trousers for his crew-work, both cheaply made. He suspected that Torg had made more than a bit of profit between what coin his father had given him and what he had actually spent. He had also supplied Wintrow with a typical sailor’s shore-clothes: a loudly-striped woven shirt and a pair of coarse black trousers, as cheaply made as his deck-clothes. They did not even fit him well, as Torg had not been too particular about size. The shirt especially hung long and full on him. His alternative was his brown priest’s robe. It was stained and worn now, darned in many places, and hemmed shorter to solve the fraying and provide material for patches. If he put it on, he would once more be proclaiming to all that this was what he was, a priest, not a sailor. He would lose what ground he had gained with his fellows.

As he donned the striped shirt and black trousers, he told himself that it was not a denial of his priesthood, but instead a practical choice. If he had gone among the folk of this strange town dressed as a priest of Sa, he would likely have been offered the largesse due a wandering priest. It would have been dishonest to seek or accept such gifts of hospitality, when he was not truly come among them as a priest but only as a visiting sailor. Resolutely he set aside the niggling discomfort that perhaps he was making too many compromises lately, that perhaps his morality was becoming too flexible. He hurried to join those going ashore.

There were five of them going ashore, including Wintrow and Mild. One of them was Comfrey, and Wintrow found that he could neither keep his eyes off the man nor meet his gaze squarely. There he sat, the man who had perpetrated the coffee cup obscenity on his father, and Wintrow could not decide whether to be horrified by him or amused. He seemed a fellow of great good cheer, making one jest after another to the rest of the crew as they leaned on the oars. He wore a ragged red cap adorned with cheap brass charms and his grin was missing a tooth. When he caught Wintrow stealing glances at him, he tipped the boy a wink and asked him loudly if he’d like to tag along to the brothel. ‘Likely the girls’ll do you for half-price. Little men like you sort of tickle their fancy is what I hear.’ And despite his embarrassment, Wintrow found himself grinning as the other men laughed. He suddenly grasped the good nature behind a great deal of the teasing.

They hauled the small boat up on the beach and pulled her well above the tide line. Their liberty would only last until sundown, and two of the men were already complaining that the best of the wine and women would not be found on the streets until after that. ‘Don’t you believe them, Wintrow,’ Comfrey said comfortingly. ‘There’s plenty to be had at any hour in Cress; those two just prefer the darkness for their pleasures. With faces like those, they need a bit of shadow even to persuade a whore to take them on. You come with me, and I’ll see you have a good time before we have to be back to the ship.’