The Name of the Star

“Your ID will get you in the front door. Simply tap it on the reader. Under no circumstances are you to give your ID to anyone else. Now, let’s look around.”

We got up and went back into the hallway. She waved her hand at a wall full of open mailboxes. There were more bulletin boards full of more notices for classes that hadn’t even started yet—reminders to get Oyster cards for the Tube, reminders to get certain books, reminders to get things at the library.

“The common room,” she said, opening a set of double doors. “You’ll be spending a lot of time here.”

This was a massive room, with a big fireplace. There was a television, a bunch of sofas, some worktables, and piles of cushions to sit on on the floor. Next to the common room, there was a study room full of desks, then another study room with a big table where you could have group sessions, then a series of increasingly tiny study rooms, some with only a single plush chair or a whiteboard on the wall.

From there, we went up three floors of wide, creaking steps. My room, number twenty-seven, was way bigger than I’d expected. The ceiling was high. There were large windows, each with a normal rectangular bit and an additional semicircle of glass on top. A thin, tan carpet had been laid on the floor. There was an amazing light hanging from the ceiling, big globes on a seven-pronged silver fixture. Best of all—there was a small fireplace. It didn’t look like it worked, but it was incredibly pretty, with a black iron grate and deep blue tiles. The mantel was large and deep, and there was a mirror mounted above it.

The thing that really got my attention, though, was the fact that there were three of everything. Three beds, three desks, three wardrobes, three bookshelves.

“It’s a triple,” I said. “I was only sent the name of one roommate.”

“That’s right. You’ll be living with Julianne Benton. She does swimming.”

That last part was delivered with a touch of annoyance. It was becoming very clear what Claudia’s priorities were.

She then showed me a tiny kitchen at the end of the hall. There was a water dispenser in the corner that had cold or boiling filtered water (“so you won’t need a kettle”). There was a small dishwasher and a very, very small fridge.

“That’s stocked daily with milk and soya milk,” Claudia said. “The fridge is for drinks only. Make sure to label your drinks. That’s what the pack of two hundred blank labels on your school supply list is for. There will be a selection of fruit and dried cereal here at all times, in case you get hungry.”

Then it was a tour of the bathroom, which was actually the most Victorian room of them all. It was massive, with a black-and-white tiled floor, marbled walls, and big beveled mirrors. There were wooden cubbies for our towels and bath supplies. For the first time, I could completely imagine all my future classmates here, all of us taking our showers and talking and brushing our teeth. I would be seeing my classmates dressed only in towels. They would see me without makeup, every day. That thought hadn’t occurred to me before. Sometimes you have to see the bathroom to know the hard reality of things.

I tried to dismiss this dawning fear as we returned to my room. Claudia rattled off rules to me for about another ten minutes. I tried to make mental notes of the ones to remember. We had to have our lights out by eleven, but we were allowed to use computers or small personal lights after that, provided that they didn’t bother our roommates. We could only put things up on our walls using something called Blu-Tack (also on the supply list). School blazers had to be worn to class, official assemblies, and dinner. We could leave them behind for breakfast and lunch.

“The dinner schedule is a bit strange tonight, since it’s just the prefects and you. The meal will be at three. I’ll send Charlotte to come get you. Charlotte is head girl.”

Prefects. I had learned this one. Student council types, but with superpowers. They who must be obeyed. Head girl was head of all girl prefects. Claudia left me, banging the door behind her. And then, it was just me. In the big room. In London.

Eight boxes were sitting on the floor. This was my new stuff, my clothes for the year: ten white dress shirts, three dark gray skirts, one gray and white striped blazer, one maroon tie, one gray sweater with the school crest on the breast, twelve pairs of gray kneesocks. In addition, there was another box of PE uniforms, for the daily physical education: two pairs of dark gray track pants with white stripes down the side, three pairs of shorts of the same material, five light gray T-shirts with WEXFORD written across the front, one maroon fleece track jacket with school crest, ten pairs of white sport socks. There were shoes as well—massive, clunky things that looked like Frankenstein shoes.

Obviously, I had to put on the uniform. The clothes were stiff and creased from packing. I yanked the pins from the shirt collars and pulled the tags from the skirt and blazer. I put on everything but the socks and shoes. Then I put on my headphones, because I find that a little music helps you adjust better.

There was no full-length mirror to gauge the effect. Using the mirror over the fireplace, I got a partial look. I still really needed to see the whole thing. That was going to require some ingenuity. I tried standing on the end of the middle bed, but it was too far over, so I pulled it into the center of the room and tried again. Now I had the complete picture. The result was a lot less gray than I’d imagined. My hair, which is a deep brown, looked black against the blazer, which I liked. The best part, without any question, was the tie. I’ve always liked ties, but it seemed like too much of a Statement to wear them. I pulled it loose, tugged it to the side, wrapped it around my head—I wanted to see every variation of the look.

Suddenly, the door opened. I screamed and knocked the headphones off my ears. They blasted music out into the room. I turned to see a tall girl standing in the doorway. She had red hair in an incredibly complicated yet casual-looking updo, and the creamy skin and heavy showers of golden freckles to match. What was most remarkable was her bearing. Her face was long, culminating in an adorable nub of a chin, which she held high. She was one of those people who actually walks with her shoulders back, like that’s normal. She was not, I noticed, wearing a uniform. She wore a blue and rose skirt with a soft gray T-shirt and a soft rose linen scarf tied loosely around her neck.

“Are you Aurora?” she asked.

She didn’t wait for me to confirm that I was this “Aurora” she was looking for.

“I’m Charlotte,” she said. “I’m here to take you to dinner.”

“Should I”—I pinched a bit of my uniform in the hope that this conveyed the verb—“change?”

“Oh, no,” she said cheerfully. “You’re fine. It’s just a handful of us, anyway. Come on!”

She watched me step awkwardly from the bed, grab my ID and key, and slip on my flip-flops.

3

I know you’re not supposed to judge people when you first meet them—but sometimes they give you lots of material to work with. For example, she kept looking sideways at my uniform. It would have been so easy for her to say, “Take a second and change,” but she hadn’t done that. I guess I could have demanded it, but I was cowed by her head girl status. Also, halfway down the stairs, she told me she was going to apply to Cambridge. Anyone who tells you their fancy college plans before they tell you their last name … these are people to watch out for. I once met a girl in line at Walmart who told me she was going to be on America’s Next Top Model. When I next saw that girl, she was crashing a shopping cart into an old lady’s car out in the parking lot. Signs. You have to read them.

I was terrified for a few minutes that they would all be like this, but reassured myself that it probably took a certain type to become head girl. I decided to deflect her attitude by giving a long, Southern answer. I come from people who know how to draw things out. Annoy a Southerner, and we will drain away the moments of your life with our slow, detailed replies until you are nothing but a husk of your former self and that much closer to death.

“New Orleans,” I said. “Well, not New Orleans, but right outside of. Well, like an hour outside of. My town is really small. It’s a swamp, actually. They drained a swamp to build our development. Well, attempting to drain a swamp is pretty pointless. They don’t really drain. You can dump as much fill on them as you want, but they’re still swamps. The only thing worse than building a housing development on a swamp is building it on an old Indian burial ground—and if there had been an old Indian burial ground around, the greedy morons who built our McMansions would have set up camp on it in a heartbeat.”

“Oh. I see.”

My answer only seemed to increase the intensity of the smug glee waves. My flip-flops made weird sucking noises on the stones.

“Your feet must be cold in those,” she said.

“They are.”

And that was the end of our conversation.

The refectory was in the old church, long deconsecrated. My hometown has three churches—all of them in prefab buildings, all filled with rows of plastic chairs. This was a Church—not large—but proper, made of stone, with buttresses and a small bell tower and narrow stained-glass windows. Inside, it was brightly lit by a number of circular black metal chandeliers. There were three long rows of wooden tables with benches, and a dais with a table where the old altar had been. There was also one of those raised side pulpits with its own set of winding stairs.

There was a small group of students sitting toward the front. Of course, none of them were in uniform. The sound of my flip-flops echoed off the walls, drawing their attention.

“Everyone,” Charlotte said, walking me up to the group, “this is Aurora. She’s from America.”

“Rory,” I said quickly. “Everyone calls me Rory. And I love uniforms. I’m going to wear mine all the time.”

“Right,” Charlotte said, before my quip could land. “And this is Jane, Clarissa, Andrew, Jerome, and Paul. Andrew is head boy.”

All the prefects were casually dressed, but in a dressy way. Like Charlotte, the other girls wore informal skirts. The guys wore polo shirts or T-shirts with logos I didn’t recognize, and looked like people in catalog ads. Out of all of them, Jerome looked the most rock-and-roll, with a slightly wild head of brown curls. He looked a lot like the guy I liked when I was in fourth grade, Doug Davenport. They both had sandy brown hair and wide noses and mouths. There was something easygoing about Jerome’s face. He looked like he smiled a lot.

“Come on, Rory!” Charlotte chirped. “This way.”

By now I resented almost everything that came out of Charlotte’s mouth. I definitely didn’t appreciate being beckoned like a pet. But I didn’t see any other course of action available, so I followed her.

To get to the food, we had to walk around the raised pulpit to a side door. We entered what had probably been the old offices or vestry. All of that had been ripped out to make a compact industrial kitchen and the customary row of steam trays. Tonight’s dinner consisted of a chicken casserole, vegetarian shepherd’s pie, a pan of roasted potatoes, green beans, and some rolls. There was a thin layer of golden grease over everything except the rolls, which was fine by me. I hadn’t eaten all day, and I had a stomach that could handle any amount of grease I could get inside it.

I took a little bit of everything as Charlotte looked over my plate. I met her eye and smiled.

When we returned, the conversation had rolled on. There was lots of stuff about “summer hols” and someone going to Kenya and someone else sailing. No one I knew went to Kenya for the summer. And I knew people with boats, but no one who “went sailing.” These people didn’t seem rich—at least, they weren’t a kind of rich I was familiar with. Rich meant stupid cars and a ridiculous house and huge parties with limos to New Orleans on your sixteenth birthday to drink nonalcoholic Hurricanes, which you swap out for real Hurricanes in the bathroom, and then you steal a duck, and then you throw up in a fountain. Okay, I was thinking of someone very specific in that case, but that was the general idea of rich that I currently held. Everyone at this table had a measure of maturity I wasn’t used to—gravitas, to use the SAT word.

“You’re from New Orleans?” Jerome asked, pulling me out of my thoughts.

“Yeah,” I said, hurrying to finish chewing. “Outside of.”

He looked like he was about to ask me something else, but Charlotte cut in.

“We have a prefects’ meeting now,” she informed me. “In here.”

I wasn’t quite done eating dessert, but I didn’t want to look like I was thrown by this.

“I’ll see you later,” I said, setting down my spoon.

Back in my room, I tried to choose a bed. I definitely didn’t want the one in the middle. I had to have some wall space. The only question was, did I go ahead and take the one by the super-cool fireplace (and therefore lay claim to the excellence of the mantel to store my stuff), or did I take the high road and choose the other side of the room?

I spent five minutes standing there, rationalizing the choice of taking the one by the fireplace. I decided it was fine for me to do this as long as I didn’t take the mantel right away. I would just take the bed and not touch the mantel for a while. Gradually, it would become mine.

That important issue resolved, I put on my headphones and turned my attention to unpacking boxes. One contained the sheets, pillows, blankets, and towels I’d had shipped over from home. It was strange to have these mundane house things show up here, in this building in the middle of London. After making up my bed, I tackled the suitcases, filling my wardrobe and the drawers. I put my photo collage of my friends from home above my desk, plus the pictures of my parents, of Uncle Bick and Cousin Diane. There was the ashtray shaped like pursed lips that I stole from our local barbecue place, Big Jim’s Pit of Love. I got out my collection of Mardi Gras beads and medallions and hung them from the end of my bed. Finally, I set up my computer and placed my three precious jars of Cheez Whiz safely on the shelf.

It was seven thirty.

I knelt on my bed and looked out the window. The sky was still bright and blue.

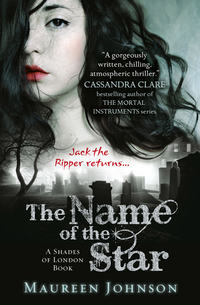

I wandered around the empty building for a while, eventually ending up in the common room. This would probably be the only time I had this room to myself, so I flopped on the sofa right in front of the television and turned it on. It was tuned to BBC One, and the news had just started. The first thing I noticed was the huge banner at the bottom of the screen that read RIPPER-LIKE MURDER IN EAST END. As I watched, through half-open eyes, I saw shots of the blocked-off street where the body was found. I saw footage of fluorescent-vested police officers holding back camera crews. Then it was back to the studio, where the announcer went on.

“Despite the fact that there was a CCTV camera pointed almost directly at the murder site, no footage of the crime was captured. Authorities say the camera malfunctioned. Questions are being raised about the maintenance of the CCTV system …”

Pigeons cooed outside the window. The building creaked and settled. I reached over and ran my hand over the heavy, slightly scratchy blue material on the sofa. I looked up at the bookcases built into the walls, stretching to the high ceiling. I had done it. This was actually London, this cold, empty building. Those pigeons were English pigeons. I had imagined this for so long, I didn’t quite know how to process the reality.

The words NEW RIPPER? flashed across the screen over a panoramic shot of Big Ben and Parliament. It was as if the news itself wanted to reassure me. Even Jack the Ripper himself had reappeared as part of the greeting committee.

4

“Oh, did we wake you?” the girl said. “We were trying not to.”

This is when I noticed the four suitcases, two laundry baskets, three boxes, and cello that were already in the room. These people had been politely creeping around for some time, trying to move in around my sleeping, uniformed body. Then I heard the racket in the hallway, the sounds of dozens of people moving in.

“Don’t worry,” the girl said. “My dad hasn’t come in. I don’t want to disturb you. You keep sleeping. Aurora, isn’t it?”

“Rory,” I said. “I fell asleep in my …”

I let the sentence go. There was no need to point out the obvious.

“Oh, it’s fine! It won’t be the last time, believe me. I’m Julianne, but everyone calls me Jazza.”

I introduced myself to Jazza’s mom, then headed down to the bathroom to brush my teeth and try to make myself generally more presentable.

The halls were swarming. How I’d slept through this invasion, I wasn’t entirely sure. Girls were squealing in delight at the sight of each other. There were hugs and air kisses, and lots of tight-lipped fights going on with parents who were trying not to make a scene. There were tears and good-byes. It was every human emotion happening at the exact same time. As I slithered down the hall, I could hear Claudia’s voice booming from three flights down, greeting people with “Call me Claudia! How was your trip? Good, good, good …”

I finally got to the bathroom and huddled by a window. Outside, it was a bright, clear morning. There were really only three or four parking spots in front of the school. The drivers had to take turns and keep their cars in nearly constant motion, dropping off a box or two and then continuing around to let the next person have a space. The same scene was going on across the square at the boys’ house.

I had planned much better entrances. I had scripted all kinds of greetings. I had gone over my best stories. But so far, I was zero for two. I brushed my teeth and rubbed my face with cold water, finger-combed my hair, and accepted that this was how I was going to meet my new roommate.

Since she was actually from England and able to come to school in a car, Jazza had way more stuff than me. Way more stuff. There were multiple suitcases, which her mom kept unpacking, piling the contents on the bed. There were boxes of books, about six dozen throw pillows, a tennis racquet, and a selection of umbrellas. Her sheets, towels, and blankets were all nicer than mine. She even brought curtains. And the cello. As for books, she easily had two hundred of them with her, maybe more. I looked over at my cardboard boxes and my decorative beads and ashtray and my one shelf of books.

“Can I help?” I asked.

“Oh …” Jazza spun around and looked at her things. “I think we’ve … I think we’ve brought it all in. My parents have a long drive back, you see, and … I’m just going to go out and say good-bye.”

“You’re done?”

“Yes, well, we’d been piling some things in the hall and bringing them in one at a time so we wouldn’t disturb you.”

Jazza went away for about twenty minutes, and when she returned, she was red-eyed and sniffly. I watched her unpack her things for a while. I wasn’t sure if I should offer my help again because the things looked kind of too personal. But I did anyway, and Jazza accepted, with many thanks. She told me I could use anything I liked, or borrow clothes, or blankets, or whatever I needed. “Just take it” was Jazza’s motto. She explained all the things that Claudia didn’t, like where and when you were allowed to use your phone (in your house and outside), what you did during the free periods (work, usually in the library or in your house).

“You lived with Charlotte before?” I asked as I made up her bed with a heavy quilt.

“You know Charlotte? She’s head girl now, so she gets her own room.”

“I had dinner with her last night,” I said. “She seems kind of … intense.”

Jazza snapped out a pillowcase.

“She’s all right, really. She’s under a lot of pressure from her family to get into Cambridge. I’d hate it if my family was like that. My parents just want me to do my best, and they’re quite happy wherever I want to go. Quite lucky, really.”

We worked right up until it was time to get ready for the Welcome Back to Wexford dinner. It wasn’t the cozy affair of the night before—the room was completely full. And this time, I wasn’t the only one in a uniform. It was gray blazers and maroon striped ties as far as the eye could see. The refectory, which had looked enormous when only a handful of us were in it the night before, had shrunk considerably. The line for food snaked all the way around to the front door. There was just enough room on the benches for everyone to squash in. There were a few more choices at dinner—roast beef, lentil roast, potatoes, several kinds of vegetables. The grease, I was happy to note, was still present.

When we emerged with our trays, Charlotte half stood and waved us over. She and Jazza exchanged some air kisses, which nauseated me a bit. Charlotte was sitting with the same group of prefects. Jerome moved over a few inches so I could sit down. We had barely applied butts to bench when Charlotte started in with the questions.

“How’s your schedule this year, Jaz?” she asked.

“Fine, thank you.”

“I’m taking four A levels, and the college I’m applying to at Cambridge requires an S level, plus I have to take the Oxbridge preparation class to get ready for the interview. So I’m going to be quite busy. Are you taking that class, the Oxbridge preparation class?”

“No,” Jazza said.

“I see. Well, it’s not strictly necessary. Where are you applying to?”

Jazza’s doelike eyes narrowed a bit, and she stabbed at her lentil roast.

“I’m still making up my mind,” she said.

“You don’t say much, do you?” Jerome asked me.

No one in my entire life had ever said this about me.

“You don’t know me yet,” I said.

“Rory was telling me she lives in a swamp,” Charlotte said.

“That’s right,” I said, turning up my accent a little. “These are the first shoes I’ve ever owned. They sure do pinch my feet.”

Jerome gave a little snort. Charlotte smiled sourly and turned the conversation back to Cambridge, a subject she seemed pathologically fixated on. People went right back to comparing notes about A levels, and I continued eating and observing.

The headmaster, Dr. Everest (it was immediately made clear to me that he was known to all as Mount Everest, which made sense, since he was about six foot seven), got up and gave us a little pep talk. Mostly it boiled down to the fact that it was autumn, and everyone was back, and while that was a great thing, people better not get cocky or misbehave or he’d personally kill us all. He didn’t actually say those words, but that was the subtext.

“Is he threatening us?” I whispered to Jerome.

Jerome didn’t turn his head, but he moved his eyes in my direction. Then he slipped a pen from his pocket and wrote the following on the back of his hand without even glancing down: Recently divorced. Also hates teenagers.

I nodded in understanding.