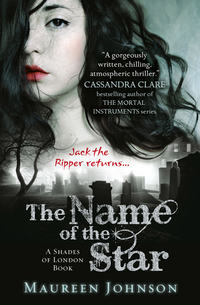

The Name of the Star

“That seems like a polite word for what she is. Is that how she got to be head girl?”

“Well …” Jazza picked at my duvet for a moment, pinching up little bits of fabric and letting them go. “The house master or mistress chooses the prefects. Claudia made her head girl, which she deserves, I suppose …”

“Did you apply?” I asked.

“You don’t apply. You just get chosen. You don’t have to be unpleasa—I mean, I like Jane a lot. And Jerome and Andrew are good friends of mine. It’s just Charlotte, well … everything was a bit of a competition. Who studied more. Who was better at sport. Who dated whom.”

Aside from being the kind of person who used “whom” correctly while gossiping, Jazza was also the kind of person who seemed pained about speaking badly about another person. She squeezed up her fists a few times, as if gossip required physical pressure to leave her body.

“When we first arrived, I was seeing Andrew for a while,” Jazza said. “Charlotte had no interest in him until I did. But she could never let something like that go. She dated him after we broke up, then she broke up with him instantly, but … she has to … well, I don’t have to live with her anymore. I live with you.”

Jazza let out a light sigh, like a demon had been released.

“Do you date someone now?” I asked.

“No,” she said. “I… no. Maybe at uni. This year, all I’m concentrating on is exams. What about you?”

I mentally paged over the short and terrible history of my love life in Bénouville. My life had been about school too. It had taken a lot of work to get into Wexford. And I wasn’t sure if a few make-outs with friends in the Walmart parking lot constituted dating. Now that I thought about it, maybe I had been waiting too—waiting to come here. In my imagination, I’d always envisioned some figure by my side at Wexford. That prospect seemed unlikely after my display tonight, unless English people were really into people who could eject food from their throats at high velocity.

“Me too,” I said. “Studying. That’s what this year is about.”

Sure, we both meant that to an extent. I had come to study. I did have to apply to college while I was here. I really was going to read those books on my shelf, and I really was excited about the prospect of my classes, even if it appeared that said classes would probably kill me. But neither of us was telling the entire truth on that count, and we both knew it. There was a look, an almost audible click as we bonded over this mutual lie. Jazza and I got each other. Perhaps she was the figure by my side that I’d always imagined.

7

I began the day with double French. At home, French was one of my strongest subjects. Louisiana has French roots. Lots of things in New Orleans have French names. I thought French was going to be my best subject, but this illusion was quickly shattered when our teacher, Madame Loos, came in rattling off French like an annoyed Parisian. I went right from there to double English Literature, where we were informed that we would be working on the period from 1711 to 1847. What alarmed me about that was its specificity. I didn’t even think it was that the material was necessarily much harder than what I had in school at home—it was more that they were so adult about it. The teachers spoke with a calm assurance, like we were all fully qualified academics, and everyone acted accordingly. We would be reading Pope, Swift, Johnson, Pepys, Fielding, Coleridge, Wordsworth, Richardson, Austen, the Brontës, Dickens … the list went on and on.

Then I had lunch. It continued to rain.

After lunch I had a free period, which I spent having a panic attack in my room.

I thought for sure that they would cancel hockey. In fact, I asked someone what we did when our sports hour was canceled because of the weather, and she just laughed. So it was off to the field in my tiny shorts and fleece, with my mouth guard, of course. The night before I had to put it in a mug of boiling water to make it soft and mold it to my teeth. That was a pleasant feeling. At the field, I was greeted with the goal-keeper equipment. I’m not sure who designed the field hockey goalie’s uniform, but I’d guess it was someone who decided to merge his or her love of safety with a truly macabre sense of humor. There were swollen blue pads for my shins that were easily twice the width of my leg. There was another set for the upper thigh. The arm pads were like massively overinflated floaties. There were chest pads with an oversized jersey to go over them and huge, cartoonish shoe objects for my feet. Then there was a helmet with a face guard. The overall effect was like one of those bodysuits you can get to make you look like a sumo wrestler—but far less elegant and human. It took me fifteen minutes to get all this stuff on, and then I had to figure out how to walk in it. The other goalie, a girl named Philippa, got hers on in half the time and was running, wide-legged, onto the field while I was still trying to get the shoes on.

Once I did that, my job was to stand in the goal while people hit hockey balls at me. Claudia kept yelling at me to repel this onslaught using my feet, but sometimes she would tell me to use my arms. All the while, rain poured onto the helmet and streamed down my face. I couldn’t move, so the balls just hit me. When it was all over, Charlotte came up to me as I was trying to get out of the padding.

“If you want some help,” she said, “I’ve been playing for a long time. I’d be happy to run drills with you.”

What was especially painful about this was that I think she meant it.

At home, I had the third-highest GPA in my class, and literature was my thing. I would do the reading for English first. The essay I had to read was called “An Essay on Criticism” by Alexander Pope.

The first challenge was that the essay was, in fact, a very long poem in “heroic couplets.” If something is called an essay, it should be an essay. I read it twice. A few lines stood out, like “For fools rush in where angels fear to tread.” Now I knew where that came from. But I still didn’t really know what it was about. I looked online first, but I quickly realized I had to up my game a little here at Wexford. This was a place for some book learning. So I went to the library.

Our school library at home was an aluminum bunker thing that they had attached to the school. It had no windows and an air conditioner that whistled. The Wexford library was a proper library. The floor was made of black-and-white stone. There were two levels of stacks—big, wooden ones. Then there was a massive work area, full of long wooden tables that had dividing walls, so you could have your own little space to sit in, with a shelf, a light, and plugs for your computer. The wall in front of you was even covered in cork and had pins, so you could tack up notes as you worked. This part was very modern and shiny, and it made me feel like a real person to sit there and work, like I really was one of these academics of Wexford. I could pretend, at least, and if I pretended long enough, maybe I could make it into a reality.

I took a seat at one of the empty cubicles and spent several minutes setting it up. I plugged in my computer. I pinned my course syllabus to the cork wall and stared it down. Everyone else in this room was calmly carrying on. No one had, to my knowledge, read their course assignments and tried to escape through a chimney. I had been admitted to Wexford, and I had to assume that they didn’t do that just to be funny.

Wexford had a large assortment of books on Alexander Pope, so I headed off to the Literature Ol–Pr section, which was on the upper level and in the back. When I got to the aisle, I found a guy lounging right in the middle of it, on the floor, reading. He was in his uniform, but wore an oversized trench coat on top of it. He had really elaborate, bleached-blond, sticky-uppy hair formed into spikes. And he was singing a song.

Panic on the streets of London,

Panic on the streets of Birmingham …

Sure, it was very romantic to lounge around in the literature section with big hair, but he was doing this in the dark. All the aisles had lights on timers. When you went into the aisle, you turned on the light. It clicked itself off after ten minutes or so. He hadn’t bothered to do this and was reading with just the scant amount of light coming from the window at the far end of the aisle. He didn’t move or look up, even when I had to stand right next to him and reach over him to get to the books. There were about ten books of collected works of Alexander Pope, which I didn’t need. I had the poem—I needed something to tell me what the hell it meant. Next to those were several books about Alexander Pope, but I had no idea which one I wanted. They were also very large. Meanwhile, the guy kept singing.

I wonder to myself,

Could life ever be sane again?

“Excuse me. Could I ask you to move a little?” I said.

He looked up slowly and blinked.

“Are you talking to me?”

There was a dim confusion in his eyes. He tucked in his knees and spun around on his butt so that he was facing up at me. Now I understood what people meant by bluebloods—he was the palest person I had ever seen, a genuine grayish-blue in the light of the aisle.

“What are you singing?” I asked. I hoped he would take that as “please stop singing.”

“It’s called ‘Panic,’” he said. “It’s by the Smiths. There’s panic on the streets now, isn’t there? Ripper and all that. Morrissey’s a prophet.”

“Oh,” I said.

“What are you looking for?”

“A book on Alexander Pope, and I—”

“For what?”

“I have to read ‘An Essay on Criticism.’ I read it, I just don’t … I need a book about it. A criticism book.”

“Then you don’t want these,” he said, standing up. “They’re all rubbish. You’ll do far better with something that puts Pope’s work into context. See, Pope was talking about the importance of good criticism. All those books are just biographies with some padding. You want the general criticism section, which is over here.”

It seemed to take extraordinary effort for him to stand up. He pulled his coat tight and shied away from me a little. Then he gave a little jerk of his spiky head to indicate that I should follow him, which I did. He maneuvered around the gloomy stacks, turning abruptly a few aisles down. He didn’t turn on the light when we went in—I had to switch it on. He also didn’t need to scan for the section or book he was looking for. He walked right to it and pointed to the red spine.

“This one. By Carter. This one talks about Pope’s role in shaping the modern critic. And this one”—he indicated a green book two shelves down—“by Dillard. A little basic, but if you’re new to criticism, worth a read.”

I decided not to be resentful of the fact that he assumed I was “new to criticism.”

“You’re American,” he said, leaning against the shelf behind us. “We don’t normally get Americans.”

“Well, you got me.”

I wasn’t sure what to do next. He wasn’t talking; he was just staring at me as I held the book. So I flipped it open and started looking at the contents. There was an entire chapter on “An Essay on Criticism.” It was twenty pages long. I could read twenty pages if it helped me look less clueless.

“I’m Rory,” I said.

“Alistair.”

“Thanks,” I said, holding up the book.

He didn’t reply. He just sat down on the floor and folded his trench-coated arms and stared up at me.

The aisle light clicked off as I left, but he didn’t move.

It was going to take some time before I understood Wexford and its ways.

8

I realized I was popular back in Bénouville, I guess. I mean, not homecoming queen material, because that always went to a Professional Pageant Quality person. But my family was Old Bénouville, and my parents were lawyers, which meant that I was basically always going to be okay. I never felt out of place. I never lacked friends. I never walked into a class without feeling like I could speak up. I was of the place. I was home.

Wexford was not my home. England was not my home.

I was not popular at Wexford. I wasn’t unpopular either. I was just there. I wasn’t the brightest, though I managed to hold my own. But I had to work harder than I’d ever worked. I often didn’t know what people were talking about. I didn’t get the jokes and the references. My voice sometimes sounded loud and odd. I got bruised from the hockey balls and the hockey ball protection I wore.

Some other facts I picked up:

Welsh is an actual, currently used language and our next-door neighbors Angela and Gaenor spoke it. It sounds like Wizard.

Baked beans are very popular in England. For breakfast. On toast. On baked potatoes. They can’t get enough.

“American History” is not a subject everywhere.

England and Britain and the United Kingdom are not the same thing. England is the country. Britain is the island containing England, Scotland, and Wales. The United Kingdom is the formal designation of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland as a political entity. If you mess this up, you will be corrected. Repeatedly.

The English will play hockey in any weather. Thunder, lightning, plague of locusts … nothing can stop the hockey. Do not fight the hockey, for the hockey will win.

Jack the Ripper struck for the second time very early on September 8, 1888.

That last fact was hammered home in about seventeen thousand ways. I didn’t even watch the news and yet, news just got in. And the news really wanted us to know about the eighth of September. The eighth of September was a Saturday. And I had art history class on Saturday. This fact seemed much more relevant to my life, being unused to the idea of Saturday class. I had always assumed the weekend was a holy tradition, respected by good people everywhere. Not so at Wexford.

But our Saturday classes were our “art and enrichment classes,” which meant that they were supposed to be marginally less painful than the classes during the week, unless you hated arts or enrichment, which I suppose some people do.

Even though Jazza tried to wake me up on her way to the shower, and again on her way to breakfast, she succeeded only when she returned to the room to get her cello for music class. I fell out of bed as she hauled the massive black case out of the room.

I wasn’t alone among the Saturday late starters. I’d already developed the habit of throwing my skirt and blazer over the end of my bed at night, so all I had to do in the morning was grab a clean shirt, pull on the skirt, shoes, and blazer, and scoop my hair up into any formation that looked reasonably like a hairstyle. I showered at night, and like Jazza, I had given up on makeup. My grandmother would have been appalled.

So I was ready in five minutes and flying down the cobblestones to the classroom building. Art history was in one of the big, airy studio rooms on the top floor. I took a seat at one of the worktables. I was still wiping the crap out of the corners of my eyes when Jerome took the seat next to me. This was the first class I had with a friend, which wasn’t that shocking, considering that my friends numbered exactly two at this point. Out of everyone I’d seen, Jerome looked the most out of place in his uniform, certainly compared to the other prefects. His special prefect tie (their ties had gray stripes) was crooked and not quite tightened at the neck. His blazer pockets bulged with stuff—phone, pens, some notes. His hair was the most unkempt—but in a good way, I thought. It looked like he had trimmed his loose curls to just the regulation level, and maybe half an inch beyond. They fell just over his ears. And you could tell he just shook it out in the morning. His eyes were quick, always scanning around for information.

“Did you hear?” he asked. “They found another body around nine this morning. It’s the Ripper, definitely.”

“Good morning,” I replied.

“Morning. Listen to this. The second victim in the Jack the Ripper murders in 1888 was found in the back of a house on Hanbury Street, in the back garden by a set of steps at five forty-five in the morning. That house is gone now, and the police were all over the location where it stood. This new victim was found behind a pub called the Flowers and Archers, which has a back garden very much like the description of the Hanbury Street murder. The second victim in 1888 was a woman called Annie Chapman. The victim this time was named Fiona Chapman. All of the wounds were just like Annie Chapman’s. The cut to the neck. The abdomen opened up. The intestines removed and put over her shoulder. Her stomach taken out and put over the opposite shoulder. The murderer took the bladder and the—”

Our teacher came in. Of all the teachers I’d had so far, this one looked the mildest. The male teachers all wore jackets or ties, and the women tended to wear dresses or serious-looking skirts and blouses. Mark, as he introduced himself, wore a plain blue sweater and a pair of jeans. He looked to be in his midthirties, with tortoiseshell glasses.

“The police aren’t even trying to deny it anymore,” Jerome said quietly, right before Mark took roll. “There’s definitely a new Ripper.”

And with that, art history began. Mark was a full-time conservationist at the National Gallery, but he was coming in to teach us about art every Saturday. We were, he informed us, going to begin with paintings from the Dutch Golden Age. He distributed some textbooks, which weighed about as much as a human head (a guesstimate on my part, obviously, but once the Ripper was mentioned, body parts tended to come to mind).

It became immediately clear that even though this was a Saturday class under the general label of “art and enrichment,” this was not just a way of killing three hours that might otherwise have been spent sleeping or eating cereal. This was a class, just like any other, and many people in it (Mark checked) were planning on taking an A level in art history. More competition.

On the positive side, Mark informed us that on several Saturdays we would be going to the National Gallery to see the paintings up close. But today was not one of those days. Today we were going to look at slides. Three hours of slides isn’t as horrible as it sounds, not when you have a reasonably interesting person who really likes what he’s talking about explaining them. And I like art.

Jerome, I noticed, was a careful note taker. He sat far back in his chair, his arm extended, writing quickly in a loose, relaxed hand, his eyes flicking between the slide and the page. I started to copy his style. He took about twenty notes on each painting, just a few words each. Every once in a while, his elbow would make contact with my arm, and he’d glance over. When class was over, we fell in step beside each other as we walked to the refectory. Jerome picked up right where he left off.

“The Flowers and Archers isn’t far from here,” he said. “We should go.”

“We … should?”

Again, I knew many students at Wexford could legally drink, because you only had to be eighteen. I knew that pubs would be a part of life here somehow. But I hadn’t expected someone, especially a prefect, to invite me to one. Also, was he asking me out? Did you ask people to crime scenes on dates? My pulse did a little leap, but it was quickly regulated by his follow-up.

“You, me, Jazza,” he said. “You should get Jazza to come, otherwise she’ll start stressing from day one. You’re her keeper now.”

“Oh,” I said, trying not to sound disappointed. “Right.”

“I have desk duty at the library until dinner, but we could go right after. What do you think?”

“Sure,” I said. “I… I mean, I don’t have plans.”

He put his hands in his pockets and took a few steps backward.

“Have to go,” he said. “Don’t tell Jazza where we’re going. Just say the pub, okay?”

“Sure,” I said.

Jerome gave a slouchy, full upper body nod and walked off to the library.

9

“Sorry,” she said, turning as I came in. “My cello practice ran late, and I didn’t feel like going over to the refectory. On Saturdays I sometimes treat myself to a sandwich and a cake.”

“Treat myself” was a little Jazza-ism I loved. Everything was a tiny celebration with her. A treat was a single cookie or a cup of hot chocolate. She made these things special. Even my Cheez Whiz had become a little treat. It was more precious now.

Something was beeping on my bed. I still wasn’t used to the unfamiliar ring and alerts of my English phone. I hadn’t even gotten into the habit of carrying it with me because there was no one likely to call me, except my parents. They had been scheduled to arrive in Bristol that morning. That’s who the message was from. I noticed an alarmed frequency in my mother’s voice.

“We think you should spend the weekends up here, in Bristol,” she said, once we’d gotten the basic hellos out of the way. “At least until this Ripper business is over.”

Alarming though Wexford could be at times, I had no desire to leave it. In fact, I was certain that if I did, I would miss crucial things—all the things that would allow me to adapt and last the entire year.

“Well, I have class on Saturday morning,” I said, “then we eat lunch. And doesn’t it take, like, hours to get there? So I wouldn’t even get there until Saturday night, and then I’d have to leave in the middle of Sunday … and I need all that time to do work. Plus, I have to play hockey every day, and since I don’t know how to play, I have to do extra practice …”

Jazza didn’t look up, but I could tell she was listening to every word of this. After ten minutes, I had convinced them that it wasn’t a good idea to leave, but I had to swear up, down, and sideways to be careful and to never, ever, ever do anything on my own. They moved on to describing their house in Bristol. I was scheduled to see it for the first time during a long weekend break in mid-November.

“Your parents are alarmed?” Jazza asked when I hung up.

I nodded and sat down on the floor.

“Mine are as well,” she said. “I think they want me to come home too, but they aren’t saying. The trip to Cornwall would be too long, anyway. And Bristol is just as bad. You’re right.”

This confirmation made me feel a bit better. I hadn’t just been making things up.

“What are you doing tonight?” I asked her.

“I thought I’d stay in and work on this German essay. And then I really need to put in a few hours of cello practice. I was in terrible shape this morning.”

“Or,” I said, “we could go out. To … a pub. With Jerome.”

Jazza chewed a strand of hair for a moment.

“To a pub? With Jerome?”

“He just asked me to ask you.”

“Jerome asked you to ask me to go to a pub?”

“He said it was my job to convince you,” I explained.

Jazza spun around in her chair and smiled broadly.

“I knew it,” she said.