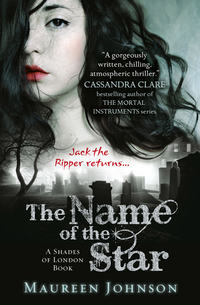

The Name of the Star

“As you are probably aware,” Everest droned on, “there’s been a murder nearby, which some people have taken to referring to as a new Ripper. Of course, there is no need to be concerned, but the police have asked us to remind all students to take extra care when leaving school grounds. I have now reminded you, and I trust no more need be said about that.”

“I feel warm and reassured,” I whispered. “He’s like Santa.”

Everest turned in our general direction for a moment, and we both stiffened and stared straight ahead. He chastised us a bit more, giving us some warnings about not staying out past our curfew, not smoking in uniform or in the buildings, and excessive drinking. Some drinking seemed to be expected. Laws were different here. You could drink at eighteen in general, but there was some weird side law about being able to order wine or beer with a meal, with an adult, at sixteen. I was still mulling this over when I noticed that the speech had ended and people were getting up and putting their trays on the racks.

I spent the night watching and occasionally assisting Jazza as she began the process of decorating her half of the room. There were curtains to be hung and posters and photos to be attached to the walls with Blu-Tack. She had an art print of Ophelia drowning in the pond, a poster from a band I’d never heard of, and a massive corkboard. The photos of her family and dogs were all in ornate frames. I made a mental note to get more wall stuff so my side didn’t look so naked.

What she didn’t display, I noticed, was a boxful of swimming medals.

“Holy crap,” I said, when she set them on the desk, “you’re like a fish.”

“Oh. Um. Well, I swim, you see.”

I saw.

“I won them last year. I wasn’t going to bring them, but … I brought them.”

She put the medals in her desk drawer.

“Do you play sports?” she asked.

“Not exactly,” I said. Which was really just my way of saying “hell, no.” We Deveauxs preferred to talk you to death, rather than face you in physical combat.

As she continued to unpack and I continued to stare at her, it occurred to me that Jazza and I were going to do this—this sitting-in-the-same-room thing—every night. For something like eight months. I had known my days of total privacy were over, but I hadn’t quite realized what that meant. All my habits were going to be on display. And Jazza seemed so straightforward and well-adjusted … What if I was a freak and had never realized it? What if I did weird things in my sleep?

I quickly dismissed these things from my mind.

5

“Quick,” Jazza said, springing out of bed with a speed that was both alarming and unacceptable at this hour.

“I can’t run in the morning,” I said, rubbing my eyes.

Jazza was already putting on her robe and picking up her towel and bath basket.

“Quick!” she said again. “Rory! Quick!”

“Quick what?”

“Just get up!”

Jazza rocked from foot to foot anxiously as I pulled myself out of bed, stretched, fumbled around filling my bath basket.

“So cold in the morning,” I said, reaching for my robe. And it really was. Our room must have dropped about ten degrees in temperature from the night before.

“Rory …”

“Coming,” I said. “Sorry.”

I require a lot of things in the morning. I have very thick, long hair that can be tamed only by the use of a small portable laboratory’s worth of products. In fact—and I am ashamed of this—one of my big fears about coming to England was having to find new hair products. That’s shameful, I know, but it took me years to come up with the system I’ve got. If I use my system, my hair looks like hair. Without my system, it goes horizontal, rising inch by inch as the humidity increases. It’s not even curly—it’s like it’s possessed. Obviously, I needed shower gel and a razor (shaving in the group shower—I hadn’t even thought about that yet) and facial cleanser. Then I needed my flip-flops so I didn’t get shower foot.

I could feel Jazza’s increasing sense of despair traveling up my spine, but I was hurrying. I wasn’t used to having to figure all these things out and carry all my stuff at six in the morning. Finally, I had everything necessary and we trundled down the hall. At first, I wondered what the fuss was about. All the doors along the hall were closed, and there was little noise. Then we got to the bathroom and opened the door.

“Oh, no,” she said.

And then I understood. The bathroom was completely packed. Everyone from the hall was already in there. Each shower stall was already taken, and three or four people were lined up by each one.

“You have to hurry,” Jazza said. “Or this happens.”

It turns out there is nothing more annoying than waiting around for other people to shower. You resent every second they spend in there. You analyze how long they are taking and speculate on what they are doing. The people in my hall showered, on average, ten minutes each, which meant that it was over a half hour before I got in. I was so full of indignation about how slow they were that I had already preplanned my every shower move. It still took me ten minutes, and I was one of the last ones out of the bathroom.

Jazza was already in our room and dressed when I stumbled back in, my hair still soaked.

“How soon can you be ready?” she asked as she pulled on her school shoes. These were by far the worst part of the uniform. They were rubbery and black, with thick, nonskid soles. My grandmother wouldn’t have worn them. But then, my grandmother was Miss Bénouville 1963 and 1964, a title largely awarded to the fanciest person who entered. In Bénouville in 1963 and 1964, the definition of fancy was highly questionable. I’m just saying, my grandmother wears heeled slippers and silk pajamas. In fact, she’d bought me some silk pajamas to bring to school. They were vaguely transparent. I’d left them at home.

I was going to tell Jazza all of this, but I could see she was not in the mood for a story. So I looked at the clock. Breakfast was in twenty minutes.

“Twenty minutes,” I said. “Easy.”

I don’t know what happened, but getting ready was just a lot more complicated than I thought it would be. I had to get all the parts of my uniform on. I had trouble with my tie. I tried to put on some makeup, but there wasn’t a lot of light by the mirror. Then I had to guess which books I had to bring for my first classes, something I probably should have done the night before.

Long story short, we left at 7:13. Jazza spent the entire wait sitting on her bed, eyes growing increasingly wide and sad. But she didn’t just leave me, and she never complained.

The refectory was packed, and loud. The bonus of being so late was that most people had gone through the food line. We were up there with the few guys who were going back for seconds. I grabbed a cup of coffee first thing and poured myself an impossibly small glass of lukewarm juice. Jazza took a sensible selection of yogurt, fruit, and whole-grain bread. I was in no mood for that kind of nonsense this morning. I helped myself to a chocolate doughnut and a sausage.

“First day,” I explained to Jazza when she stared at my plate.

It became clear that it was going to be tricky to find a seat. We found two at the very end of one of the long tables. For some reason, I looked around for Jerome. He was at the far end of the next table over, deep in conversation with some girls from the first floor of Hawthorne. I turned to my plate of fats. I realized how American this made me seem, but I didn’t particularly care. I had just enough time to stuff some food down my throat before Mount Everest stood up at his dais and told us that it was time to move along. Suddenly, everyone was moving, shoving last bits of toast and final gulps of juice into their mouths.

“Good luck today,” Jazza said, getting up. “See you at dinner.”

The day was ridiculous.

In fact, the situation was so serious I thought they had to be joking—like maybe they staged a special first day just to psych people out. I had one class in the morning, the mysteriously named “Further Maths.” It was two hours long and so deeply frightening that I think I went into a trance. Then I had two free periods, which I had laughingly dismissed when I first saw them. I spent them feverishly trying to do the problem sets.

At a quarter to three, I had to run back to my room and change into shorts, sweatpants, a T-shirt, a fleece, and these shin pads and spiked shoes that Claudia had given to me. From there, I had to get three streets over to the field we shared with a local university. If cobblestones are a tricky walk in flip-flops, they are your worst nightmare in spiked shoes and with big, weird pads on your shins. I arrived to find that people (all girls) were (wisely) putting on their spiked shoes and pads there, and that everyone was wearing only shorts and T-shirts. Off came the sweatpants and fleece. Back on with the weird pads and spikes.

Charlotte, I was dismayed to find, was in hockey as well. So was my neighbor Eloise. She lived across the hall from us in the only single. She had a jet-black pixie cut and a carefully covered arm of tattoos. She had a huge air purifier in her room, which had gotten some kind of special clearance (since we couldn’t have appliances). Somehow she got a doctor to say she had terrible allergies, hence she would need the purifier and her own space. In reality, she used the filter to hide the fact that she spent most of her free time smoking cigarette after cigarette and blowing smoke directly into the purifier. Eloise spoke fluent French because she lived there a few months out of every year. As for the smoking, she never actually said, “It’s a French thing,” but it was implied. Eloise looked as dismayed as I did about the hockey. The rest looked grimly determined.

Most people had their own hockey sticks, but for those of us who didn’t, they were distributed. Then we stood in line, where I shivered.

“Welcome to hockey!” Claudia boomed. “Most of you have played hockey before—we’re just going to run through some basics and drills to get back into things.”

It became pretty obvious pretty quickly that “most of you have played hockey before” actually meant “every single one of you except for Rory has played hockey before.” No one but me needed the primer on how to hold the stick, which side of the stick to hit the ball with (the flat one, not the roundy one). No one needed to be shown how to run with the stick or how to hit the ball. The total amount of time given to these topics was five minutes. Claudia gave us all a once-over to make sure we were properly dressed and had everything we needed. She stopped at me.

“Mouth guard, Aurora?”

Mouth guard. Some lump of plastic she had left by my door during the morning. I’d forgotten it.

“Tomorrow,” she said. “For now, you’ll just watch.”

So I sat on the grass on the side of the field while everyone else put their plastic lumps in their mouths, turning the space previously full of teeth into alarming leers of bright pink and neon blue. They ran up and down the field, passing the ball back and forth to each other. Claudia paced alongside the entire time, barking commands I didn’t understand. The process of hitting the ball looked straightforward enough from where I was, but these things never are.

“Tomorrow,” she said to me when the period was over and everyone left the field. “Mouth guard. And I think we’ll start you in goal.”

Goal sounded like a special job. I didn’t want a special job, unless that special job involved sitting on the side under a pile of blankets.

Then we all ran back to Hawthorne—and I mean ran, literally—where everyone was once again competing for the showers. I found Jazza back in our room, dry and dressed. Apparently, there were showers at the pool.

Dinner featured some baked potatoes, some soup, and something called a “hot pot,” which looked like beef and potatoes, so I took that. Our groupings were becoming more predictable, and I was starting to understand the dynamic. Jerome, Andrew, Charlotte, and Jazza had all been friends last year. Three of them had become prefects; Jazza had not. Jazza and Charlotte didn’t get along. I attempted to join in the conversations, but found I didn’t have much to share until the topic came around to the Ripper, when I dove in with a little family history.

“People love murderers,” I said. “My cousin Diane used to date a guy on death row in Texas. Well, I don’t know if they were dating, but she used to write him letters all the time, and she said they were in love and going to get married. But it turns out he had, like, six girlfriends, so they broke up and she opened her Healing Angel Ministry …”

I had them now. They had all slowed their eating and were looking over.

“See,” I said, “Cousin Diane runs the Healing Angel Ministry out of her living room. Well, and also her backyard. She has a hundred sixty-one statues of angels in her backyard. Plus she has eight hundred seventy-five angel figurines, dolls, and pictures in the house. And people go to her for angel counseling.”

“Angel counseling?” Jazza repeated.

“Yep. She plays New Age music and has you close your eyes, and then she channels some angels. She tells you their names and what colors their auras are and what they’re trying to tell you.”

“Is your cousin … insane?” Jerome asked.

“I don’t think she’s insane,” I said, digging into my hot pot. “This one time, I was over at her house. When I get bored there, I channel angels, so she feels like she’s doing a good job. I go like this …”

I took a big, deep breath to prepare for my angel voice. Unfortunately, I did so while taking a bite of the hot pot. A chunk of beef slipped down my throat. I felt it stop somewhere just under my chin. I tried to clear my throat, but nothing happened. I tried to cough. Nothing. I tried to speak. Nothing.

Everyone was watching me. Maybe they thought this was part of the imitation. I pushed away from the table a bit and tried to cough harder, then harder still, but my efforts made no difference. My throat was stopped. My eyes watered so much that everything went all runny. I felt a rush of adrenaline … then everything went white for a second, completely, totally, brilliantly white. The entire refectory vanished and was replaced by this endless, paperlike vista. I could still feel and hear, but I seemed to be somewhere else, somewhere without air, somewhere where everything was made of light. Even when I closed my eyes, it was there. Someone was yelling that I was choking, but the words sounded like they were far away.

And then arms were around my middle. There was a fist jabbing into the soft tissue under my rib cage. I was jerked up, over and over, until I felt a movement. The refectory dropped back into place as the beef launched itself out of me and flew off in the direction of the setting sun and a rush of air came into my lungs.

“Are you all right?” someone said. “Can you speak? Try to speak.”

“I…”

I could speak, and that was all I felt like saying at the moment. I fell against the bench and put my head on the table. There was a pounding of blood in my ears. I looked deep into the markings of the wood and examined the silverware up close. My face was wet with tears I didn’t remember crying. The refectory had gone totally silent. At least, I think it was silent. My heart was drumming in my ears so loudly that it drowned out anything else. Someone was telling people to move back and give me air. Someone else was helping me up. Then some teacher (I think it was a teacher) was in front of me, and Charlotte was there as well, poking her big red head into the frame.

“I’m fine,” I said hoarsely. I wasn’t fine. I just wanted to leave, to go somewhere and cry. I heard the teacher person say, “Charlotte, take her to the san.” Charlotte attached herself to my right arm. Jazza attached herself to my left.

“I’ve got her,” Charlotte said crisply. “You can continue eating.”

“I’m coming,” Jazza shot back.

“I can walk,” I croaked.

Neither one of them loosened their grip, which was probably for the best, because it turned out my ankles and knees had gone all rubbery. They escorted me down the center aisle, between the long benches, as people turned and watched me go. Considering that the refectory was an old church, our exit probably looked like the end of a very unusual wedding ceremony—me being dragged down the aisle by my two brides.

6

I kicked off my shoes and curled up in bed. Though the offending beef was long gone, I rubbed at my throat where it had been. The feeling was still with me, that feeling of having no air, of not being able to speak.

“I’ll make you some tea,” Jazza said.

She went off and made me the tea, and I sat in my bed and gripped my throat. Though my heart had slowed to normal, there was still a tremor running through me. I picked up my phone to call my parents, but then tears started trickling from my eyes, so I shoved the phone under my blanket. I bunched myself up and took a few deep breaths. I needed to get this under control. I was fine. Nothing had happened to me. I couldn’t be the pathetic, weepy, useless roommate. I had wiped my face clean and was smiling, kind of, when Jazza returned. She handed me the tea, went to her desk and got something, then sat on the floor by my bed.

“When I have a bad night,” she said, “I look at my dogs.”

She held out a picture of two beautiful dogs—one smallish golden retriever and one very large black Lab. In the picture, Jazza was squeezing the dogs. In the background, there were green rolling hills and some kind of large white farmhouse. It looked too idyllic for anyone to actually live there.

“The golden one is Belle, and the big, soppy one is Wiggy. Wiggy sleeps in my bed at night. And that’s our house in the back.”

“Where do you live?”

“In a village in Cornwall outside of St. Austell. You should come sometime. It’s really beautiful.”

I slowly sipped my tea. It hurt my throat at first, but then the heat felt good. I reached over and got my computer and pulled up some pictures of my own. First, I showed her Cousin Diane, because I had just been talking about the angels. I had a very good picture of her standing in her living room, surrounded by figurines.

“You weren’t lying,” Jazza said, leaning on the bed and looking closely. “There must be hundreds of them!”

“I don’t lie,” I said. I flicked next to a picture of Uncle Bick.

“I can see the resemblance,” Jazza said.

She was right. Of all the members of my family, I looked most like him—dark hair, dark eyes, a very round face. Except I’m a girl, and I have fairly ample boobs and hips, and he’s a man in his thirties with a beard. But if I wore a fake black beard and a baseball cap that said BIRDBRAIN, I think people would immediately know we were related.

“He looks very young.”

“Oh, this is an old picture,” I said. “I think this was taken around the time I was born. It’s his favorite picture, so it’s the one I brought.”

“This is his favorite? It looks like it was taken in a supermarket.”

“See that woman kind of hiding behind the pile of cans of cranberry sauce?” I asked. “That’s Miss Gina. She runs the local Kroger—that’s a grocery store. Uncle Bick’s been courting her for nineteen years. This is the only picture of the two of them, which is why he likes it.”

“What do you mean, ‘courting her for nineteen years’?” Jazza asked.

“See, my uncle Bick—he’s really nice, by the way—he runs an exotic bird store called A Bird in the Hand. His life is pretty much all birds. He’s been in love with Miss Gina since high school, but he doesn’t really know how to talk to girls, so he’s just been … staying around her since then. He just tends to go where she goes.”

“Isn’t that stalking?” Jazza said.

“Legally, no,” I replied. “I asked my parents this when I was little. What he does is creepy and socially awkward, but it’s not actually stalking. I think the worst it ever got was the time he left a collage of bird feathers on the windshield of her car …”

“But doesn’t he scare her?”

“Miss Gina?” I laughed. “No. She has a whole bunch of guns.”

I made that last part up just to entertain Jazza. I don’t think Miss Gina has any guns. I mean, she might. Lots of people in our town do. But it’s hard to explain to someone who doesn’t know him that Uncle Bick is actually harmless. You only have to see him with a miniature parrot to know this man couldn’t harm anything or anyone. Also, my mom would have him locked up in a flash if she thought he was actually up to something.

“I feel quite boring next to you,” Jazza said.

“Boring?” I repeated. “You’re English.”

“Yes. That’s not very interesting.”

“You … have a cello! And dogs! And you live in a farmhouse … kind of thing. In a village.”

“Again, that’s not very exciting. I love our village, but we’re all quite … normal.”

“In our town,” I said solemnly, “that would make you a kind of god.”

She laughed a little.

“I’m not kidding,” I said. “My family—I mean, my mom and dad and me—are the normal people in town. For example, there’s my uncle Will. He owns eight freezers.”

“That doesn’t sound so odd.”

“Seven of them are on the second floor, in a spare bedroom. He also doesn’t believe in banks, so he keeps his money in peanut butter jars in the closet. When I was little, he used to give me empty jars as gifts so I could collect money and watch it grow.”

“Oh,” she said.

“Then there’s Billy Mack, who started his own religion out of his garage, the People’s Church of Universal People. Even my grandmother, who is almost normal, poses for a formal photograph each year in a slightly revealing dress and mails said photo to all her friends and family, including my dad, who shreds it without opening the envelope. This is what my town is like.”

Jazza was quiet for a moment.

“I very much want to go to your town,” she finally said. “I’m always the boring one.”

From the way she said it, I got the impression that this was something Jazza felt deeply.

“You don’t seem boring to me,” I said.

“You don’t really know me yet. And I don’t have all of this.”

She waved at my computer to indicate my life in general.

“But you have all of this,” I said. I waved my arms too in an attempt to indicate Wexford and England in general, but it looked more like I was shaking invisible pom-poms.

I sipped my tea. My throat was feeling more normal now. Every once in a while, I would remember what it was like not being able to breathe and that strange whiteness …

“You don’t like Charlotte,” I said, blinking hard. I had to say something to get all that stuff out of my head. It was probably a little abrupt and rude.

Jazza’s mouth twitched. “She’s … competitive.”