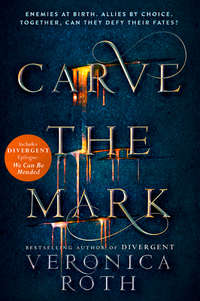

Carve the Mark

Ryzek grinned the way he always did when he knew something other people didn’t.

“‘To see the future of the galaxy,’” Ryzek quoted, in Shotet this time. “In other words, to be this planet’s next oracle.”

Akos was silent.

I sat back from the crack in the wall, closing my eyes against the line of light so I could think.

For my brother and my father, every sojourn since Ryzek was young had been a search for an oracle, and every search had turned up empty. Likely because it was nearly impossible to catch someone who knew you were coming. Or someone who might lay on a blade to avoid capture, as the elder oracle had in the same invasion that had brought the Kereseths here.

But finally, it seemed Ryzek had found a solution: he had gone after two oracles at once. One had avoided being taken by dying. And the other—this Eijeh Kereseth—didn’t know what he was. He was still soft and pliable enough to be shaped by Noavek cruelty.

I sat forward again to hear Eijeh speak, his curly head tipped forward.

“Akos, what is he saying?” Eijeh asked in slippery Thuvhesit, wiping his nose with the back of his hand.

“He’s saying they didn’t come to Thuvhe for me,” Akos said, without looking back. It was strange to hear someone speak two languages so perfectly, without an accent. I envied him the ability. “They came for you.”

“For me?” Eijeh’s eyes were pale green. An unusual color, like iridescent insect wings, or the currentstream after the Deadening time. Against his light brown skin, so like the milky earth of the planet Zold, they almost glowed. “Why?”

“Because you are the next oracle of this planet,” Ryzek said to Eijeh in the boy’s mother tongue, stepping down from the platform with the knife in hand. “You will see the future, in all its many, many varieties. And there is one variety in particular that I wish to know about.”

A shadow darted across the back of my hand like an insect, my currentgift making my knuckles ache like they were breaking. I stifled a groan. I knew what future Ryzek wanted: to rule Thuvhe, as well as Shotet, to conquer our enemies, to be recognized as a legitimate world leader by the Assembly. But his fate hung over him as heavily as Akos’s likely now hung over him, saying that Ryzek would fall to our enemies instead of reign over them. He needed an oracle if he wanted to avoid that failure. And now he had one.

I wanted Shotet to be recognized as a nation instead of a collection of rebellious upstarts just as much as my brother did. So why was the pain of my currentgift—ever-present—mounting by the second?

“I …” Eijeh was watching the knife in Ryzek’s hand. “I’m not an oracle, I’ve never had a vision, I can’t … I can’t possibly …”

I pressed against my stomach again.

Ryzek balanced the knife on his palm and flicked it to turn it. It wobbled, moving in a slow circle. No, no, no, I found myself thinking, unsure why.

Akos shifted into the path between Ryzek and Eijeh, as if he could stop my brother with the meat of his body alone.

Ryzek watched his knife turn as he moved toward Eijeh.

“Then you must learn to see the future quickly,” Ryzek said. “Because I want you to find me the version of the future I need, and tell me what it is I must do to get to it. Why don’t we start with a version of the future in which Shotet, not Thuvhe, controls this planet—hmm?”

He nodded to Vas, who forced Eijeh to his knees. Ryzek caught the blade by its handle and touched the edge of it to Eijeh’s head, right under his ear. Eijeh whimpered.

“I can’t—” Eijeh said. “I don’t know how to summon visions, I don’t—”

And then Akos barreled into my brother from the side. He wasn’t big enough to topple Ryzek, but he had caught him off guard, and Ryzek stumbled. Akos pulled his elbow back to punch—stupid, I thought to myself—but Ryzek was too fast. He kicked up from the ground, hitting Akos in the stomach, then stood. He grabbed Akos by the hair, wrenching his head up, and sliced along Akos’s jawline, ear to chin. Akos screamed.

It was one of Ryzek’s preferred places for cutting people. When he decided to give a person a scar, he wanted it to be visible. Unavoidable.

“Please,” Eijeh said. “Please, I don’t know how to do what you ask, please don’t hurt him, don’t hurt me, please—”

Ryzek stared down at Akos, who was clutching his face, his neck streaked with blood.

“I do not know this Thuvhesit word, ‘please,’” Ryzek said.

Later that night I heard a scream echoing in the quiet hallways of Noavek manor. I knew it didn’t belong to Akos—he had been sent to our cousin Vakrez, “to grow thicker skin,” as Ryzek put it. Instead I recognized the scream as Eijeh’s voice raised in acknowledgment of pain, as my brother tried to pry the future from his head.

I dreamt of it for a long time thereafter.

I WOKE WITH A groan. Someone was knocking.

My bedroom looked like a guest room, no personal touches, all the clothes and beloved objects hidden in drawers or behind cabinet doors. This drafty house, with its polished wood floors and grand candelabras, held bad memories like too much dinner. Last night one of those memories—of Akos Kereseth’s blood trailing down his throat, two seasons earlier—had come into my dreams.

I didn’t want to take root in this place.

I sat up and dragged the heels of my hands over my cheeks to smear the tears away. To call it crying would have been inaccurate; it was more an involuntary oozing, brought on by particularly strong surges of pain, often while I slept. I raked my fingers through my hair and stumbled to the door, greeting Vas with a grunt.

“What?” I said, pacing away. Sometimes it helped to pace the room—it was soothing, like being rocked.

“I see I’ve found you in a good mood,” Vas said. “Were you sleeping? You do realize it’s well into the afternoon?”

“I don’t expect you to understand,” I said. After all, Vas didn’t feel pain. That meant he was the only person I had encountered since I had developed my currentgift who could touch me with bare hands, and he liked to make sure I remembered that. When you get older, he sometimes said to me when Ryzek couldn’t hear him, you may see value in my touch, little Cyra. And I always told him I would rather die alone. It was true.

That he couldn’t feel pain also meant he didn’t know about the gray space just beneath consciousness that made it more bearable.

“Ah,” Vas said. “Well, your presence has been requested in the dining room this evening for a meal with Ryzek’s closest supporters. Dress nicely.”

“I’m not really feeling up for a social engagement right now,” I said, teeth gritted. “Send my regrets.”

“I said ‘requested,’ but maybe I should have chosen my words more carefully,” Vas said. “‘Required’ was the word your brother used.”

I closed my eyes, stalling in my pacing for a moment. Whenever Ryzek demanded my attendance, it was to intimidate, even when he was dining with his own friends. There was a Shotet saying—a good soldier does not even dine with friends unarmed. And I armed him.

“I came prepared.” Vas held out a small brown bottle, corked with wax. It wasn’t labeled, but I knew what it was anyway: the only painkiller strong enough to make me fit for polite company. Or fit enough, anyway.

“How am I supposed to eat dinner while I’m on that stuff? I’ll throw up on the guests.” It might improve some of them.

“Don’t eat.” Vas shrugged. “But you can’t really function without it, can you?”

I snatched the bottle from his hand, and nudged the door closed with my heel.

I spent a good part of the afternoon crouched in the bathroom, under a stream of warm water, willing the tension from my muscles. It didn’t help.

And so I uncorked the bottle and drank.

As revenge, I wore one of my mother’s dresses to the dining room that evening. It was light blue and fell straight to my feet, its bodice embroidered with a small geometric pattern that reminded me of feathers layered over each other. I knew it would hurt my brother to see me in it—to see me in anything she had ever worn—but he wouldn’t be able to say anything about it. I was, after all, dressed nicely. As instructed.

It had taken me ten minutes to fasten it closed, my fingertips were so numb from the painkiller. And as I walked the halls, I kept one hand on the wall to steady myself. Everything tipped and swayed and spun. I carried my shoes in my other hand—I would put them on right before I entered the room, so I wouldn’t slip on the polished wood floors.

The shadows spread down my bare arms from shoulder to wrist, then wrapped around my fingers, pooling beneath my fingernails. Pain seared me wherever they went, dulled by drugs but not eliminated. I shook my head at the guard outside the dining room doors to stop him from opening them, and stepped into my shoes.

“Okay, go ahead,” I said, and he pulled the handles apart.

The dining room was grand but warm, lit by lanterns that glowed on the long table and the fire along the back wall. Ryzek stood, bathed in light, with a drink in his hand and Yma Zetsyvis at his right. Yma was married to a close friend of my mother’s, Uzul Zetsyvis. Though she was relatively young—younger than Uzul, at least—her hair was bright white, her eyes a shocking blue. She was always smiling.

I knew the names of everyone else gathered around them: Vas, of course, at my brother’s left. His cousin, Suzao Kuzar, eagerly laughing at something Ryzek had said a moment before; our cousin Vakrez, who trained the soldiers, and his husband, Malan, swallowing the rest of his drink in one gulp; Uzul, and his and Yma’s grown daughter, Lety, with the long bright braid; and last, Zeg Radix, who I had last seen at his brother Kalmev’s funeral. The funeral of the man Akos Kereseth had killed.

“Ah, there she is,” Ryzek said, gesturing toward me. “You all remember my sister, Cyra.”

“Wearing her mother’s clothes,” Yma remarked. “How lovely.”

“My brother told me to dress nicely,” I said, working to enunciate though my lips were numb. “And no one knew the art of dressing nicely like our mother.”

Ryzek’s eyes glittered with malice. He lifted his glass. “To Ylira Noavek,” he said. “The current will carry her on a path of wonder.”

Everyone else raised their glasses and drank. I refused the glass offered to me by a silent servant—my throat was too tight for me to swallow. Ryzek’s toast was a repetition of what the priest had said at my mother’s funeral. Ryzek wanted to remind me of it.

“Come here, little Cyra, and let me have a look at you,” Yma Zetsyvis said. “Not so little anymore, I suppose. How old are you?”

“I’ve sojourned ten times,” I said, using the traditional time reference—marking what I had survived rather than how long I had existed. Then I clarified, “I began early, though—I’ll be sixteen seasons in a few days.”

“Oh, to be young and think in days!” Yma laughed. “So, still a child, then, tall as you are.”

Yma had a gift for elegant insults. Calling me a child was one of her mildest ones, I was sure. I stepped into the firelight with a small smile.

“Lety, you’ve met Cyra, haven’t you?” Yma said to her daughter. Lety Zetsyvis was a head smaller than I was, though several seasons older, and a charm hung in the hollow of her throat, a fenzu trapped in glass. It still glowed, though dead.

“No, I haven’t,” Lety said. “I would shake your hand, Cyra, but …”

She shrugged. My shadows, as if responding to her call, darted across my chest and throat. I stifled a groan.

“Let’s hope you never earn the privilege,” I said coolly. Lety’s eyes widened, and everyone went quiet. Too late, I realized that I was only playing into Ryzek’s hands; he wanted them to fear me, even though they followed him devoutly, and I was making it so.

“Your sister has sharp teeth,” Yma said to Ryzek. “Bad for those who would oppose you.”

“But no better for my friends, it seems,” Ryzek said. “I haven’t yet taught her when not to bite.”

I scowled at him. But before I could bite again—so to speak—the conversation moved on.

“How is our recent batch of recruits?” Vas asked my cousin Vakrez. He was tall, handsome, but old enough that there were creases at the corners of his eyes even when he wasn’t smiling. A deep scar, shaped like a half circle, was etched in the center of his cheek.

“Fair,” Vakrez said. “Better, now they’re through the first round.”

“Is that why you’re back for a visit?” Yma asked him. The army trained closer to the Divide, outside Voa, so it had been a few hours’ journey for Vakrez to make it here.

“No. Had to deliver Kereseth,” Vakrez said, nodding to Ryzek. “The younger Kereseth, that is.”

“His skin any thicker than when you first got him?” Suzao asked. He was a short man, but he was tough as armor skin, crisscrossed with scars. “When we took him, it was touch him and—wham!—he bruises.”

The others laughed. I remembered how Akos Kereseth had looked when he was first dragged into this house, his sobbing brother at his heels, blood still dried on his hand from his first kill mark. He had not seemed weak to me.

“Not so thin-skinned,” Zeg Radix said gruffly. “Unless you’re suggesting that my brother Kalmev died so easily?”

Suzao looked away.

“I am sure,” Ryzek said smoothly, “that no one means to insult Kalmev, Zeg. My father was killed by someone who was unworthy of him, too.” He sipped his drink. “Now, before we eat, I have arranged for some entertainment for us.”

I tensed as the doors opened, sure that whatever Ryzek called “entertainment” was much worse than it sounded. But it was just a woman, dressed throat to ankle in tight, dark fabric that showed every muscle, every bony joint. Her eyes and lips were traced with some kind of pale chalk, garish.

“My sisters and I, of the planet Ogra, offer the Shotet our greetings,” the woman said, her voice raspy. “And we present to you a dance.”

At her last word, she brought her hands together in a sharp clap. All at once, the fire in the fireplace and the shifting glow from the fenzu disappeared, leaving us in darkness. Ogra, a planet wreathed in shadow, was a mystery to most in our galaxy. Ograns did not allow many visitors, and even the most sophisticated surveillance technology couldn’t penetrate their atmosphere. The most anyone knew about them was from observation of spectacles like these. For once, I was grateful for how freely Ryzek indulged in the offerings of other planets, while restricting the rest of Shotet from doing the same. Without that hypocrisy I would never have gotten to see this.

Eager, I tilted forward on my toes and waited. Tendrils of light wrapped around the Ogran dancer’s clasped hands, weaving between her fingers. When she pulled her palms apart, the orange tongues of fire from the fireplace stayed in one palm and the blueish orbs of fenzu glow stayed hovering in the other. The faint light made the chalk around her eyes and mouth stand out, and when she smiled, her teeth were fangs in the dark.

Two other dancers filed into the room behind her. They were still for a few long moments, and movement came slowly, when it did. The dancer farthest to the left tapped her breastbone, lightly, but it wasn’t the sound of skin on skin that came from the motion—it was the sound of a full-bellied drum. The next dancer moved to that off-kilter rhythm, her stomach contracting and her back rounding as her shoulders hunched. Her body found a curved shape, and then light shuddered through her skeleton, making her spine glow, every vertebra visible for a few faltering seconds.

I gasped, along with several others.

The light-handler twisted her hands, bending firelight around fenzu light like she was weaving a tapestry from them. Their glow revealed complex, almost mechanical movements in her fingers and wrists. As the rhythm from the chest-drummer changed, the light-handler joined the third, the one with glowing bones, in a lurching, stumbling dance. I tensed, watching them, not sure if I should be disturbed or amazed. Every other moment I felt like they were going to lose their balance and hit the floor, but they caught each other every time, swinging and tilting, lifting and twisting, all flashing with multicolored light.

I was breathless when the performance ended. Ryzek led us in our applause, which I joined reluctantly, feeling it unequal to what I had just seen. The light-handler sent the flames back into our fire and the glow back into our fenzu lights. The three women clasped hands and bowed for us, smiling with closed lips.

I wanted to speak to them—though I didn’t know what I could possibly say—but they were already filing out. As the third dancer made her way to the door, though, she pinched the fabric of my skirt between her thumb and forefinger. Her “sisters” stopped with her. The force of all their eyes on me at once was overwhelming—their irises were pitch-black, and took up more space than usual, I was certain. I wanted to shrivel before them.

“She is herself a small Ogra,” the third dancer said, and the bones in her fingers flickered with light, just as shadows wound around my arms like bracelets. “All clothed in darkness.”

“It is a gift,” the light-handler said.

“It is a gift,” the chest-drummer echoed.

I did not agree.

The fire in the dining room was just embers. My plate was full of half-eaten food—the shreds of roasted deadbird, pickled saltfruit, and some kind of leafy concoction dusted with spices—and my head was throbbing. I nibbled the corner of a piece of bread and listened to Uzul Zetsyvis brag about his investments.

The Zetsyvis family had been charged with the breeding and harvesting of fenzu from the forests north of Voa for almost one hundred seasons. In Shotet we used the bioluminescent insects for light more often than current-channeling devices, unlike the rest of the galaxy. It was a relic of our religious history, now waning—only the truly religious didn’t use the current casually.

Maybe because of the Zetsyvis family industry, Uzul, Yma, and Lety were highly religious, refusing to take hushflower even in medicine, which meant eschewing most medicine. They said any substance that altered a person’s “natural state,” even anesthesia, defied the current. They also wouldn’t travel by current-powered engines. They considered them to be a too-frivolous use of the current’s energy—except for the sojourn ship, of course, which they defined as a religious rite. Their glasses were all full of water instead of fermented feathergrass.

“Of course, it’s been a difficult season,” Uzul said. “At this point in our planet’s rotation, the air doesn’t get warm enough to foster fenzu growth properly, so we have to introduce roving heat systems—”

Meanwhile, on my right, Suzao and Vakrez were having some kind of tense discussion about weaponry.

“All I’m saying is—regardless of what our ancestors believed—currentblades aren’t sufficient for all forms of combat. Long-range or in-space combat, for example—”

“Any idiot can fire a currentblast,” Suzao snapped. “You want us to put our currentblades down and turn soft and doughy year by year, like the Assembly nation-planets?”

“They’re not so doughy,” Vakrez said. “Malan translates Othyrian for the Shotet news feed; he’s showed me the reports.” Most of the people in this room, being Shotet elite, spoke more than one language. Outside of this room, that was prohibited. “Things are getting tense between the oracles and the Assembly, and there are whispers the planets are choosing sides. In some cases getting ready for a greater conflict than we’ve ever seen. And who knows what kind of weapons tech they’ll have by the time that conflict happens? Do you really want us to be left behind?”

“Whispers,” Suzao scoffed. “You put too much stock in gossip, Vakrez, and always have.”

“There is a reason Ryzek wants an alliance with the Pithar, and it isn’t because he likes the ocean views,” Vakrez said. “They’ve got something we can use.”

“We’re doing just fine with Shotet mettle alone, is my point.”

“Go ahead and tell Ryzek that. I’m sure he’ll listen to you.”

Across from me, Lety’s eyes were focused on the webs of dark color that stained my skin, surging into new places every few seconds—the crook of my elbow, the rise of my collarbone, the corner of my jaw.

“What do they feel like to you?” she asked me when she caught my eye.

“I don’t know, what does any gift feel like?” I said irritably.

“Well, I just remember things. Everything. Vividly,” she said. “So my gift feels like anyone else’s … Like ringing in my ears, like energy.”

“Energy.” Or agony. “That sounds right.”

I swallowed some of the fermented feathergrass in my glass. Her face was a steady pinhole with everything spinning around it; I fought to focus on her, spilling some of the drink on my chin.

“I find your fasci—” I paused. Fascination was a difficult word to say with so much painkiller coursing through my veins. “Your curiosity about my gift a little strange.”

“People are so afraid of you,” Lety said. “I simply want to know if I should be, too.”

I was about to answer, when Ryzek stood at the end of the table, his long fingers framing his empty plate. His rise was a signal for everyone to leave, and they trickled out, Suzao first, then Zeg, then Vakrez and Malan.

But when Uzul began to move toward the door, Ryzek stopped him with a hand.

“I’d like to speak with you and your family, Uzul,” Ryzek said.

I struggled to my feet, using the table to balance. Behind me, Vas pushed a bar across the door handles, locking us in. Locking me in.

“Oh, Uzul,” Ryzek said with a faint smile. “I’m afraid tonight is going to be very difficult for you. You see, your wife told me something interesting.”

Uzul looked to Yma. Her ever-present smile was finally gone, and now she looked equal parts accusatory and afraid. I was sure she wasn’t afraid of Uzul. Even his appearance was harmless—he had a round stomach, a sign of his wealth, and feet that turned out a little when he walked, giving his gait a slight hobble.

“Yma?” Uzul said to his wife weakly.

“I didn’t have a choice,” Yma said. “I was looking for a network address, and I saw your contact history. I saw coordinates there, and I remembered you talking about the exile colony—”

The exile colony. When I was young, it was just a joke that people told, that a lot of Shotet who had met with my father’s displeasure had set up a home on another planet where they couldn’t be discovered. As I grew older, the joke became a rumor, and a serious one. Even now, the mention of it made Ryzek work his jaw like he was trying to tear off a bite of old meat. He considered the exiles, as enemies of my father and even my grandmother, to be one of the highest threats to his sovereignty that existed. Every Shotet had to be under his control, or he would never feel secure. If Uzul had contacted them, it was treason.

Ryzek pulled a chair from the table, and gestured to it. “Sit.”

Uzul did as he was told.

“Cyra,” Ryzek said to me. “Come here.”

At first I just stood by my place at the table, clutching the glass of fermented feathergrass. I clenched my jaw as my body filled with shadows, like black blood from broken vessels.

“Cyra,” Ryzek said quietly.

He didn’t need to threaten me. I would set my glass down and walk over to him and do whatever he told me. I would always do that, for as long as we both lived, or Ryzek would tell everyone what I had done to our mother. That knowledge was a stone in my stomach.

I put my glass down. I walked over to him. And when Ryzek told me to put my hands on Uzul Zetsyvis until he gave whatever information Ryzek needed to know, I did.

I felt the connection form between Uzul and me, and the temptation to force all the shadow into him, to stain him black as space and end my own agony. I could kill him if I wanted to, with just my touch. I had done it before. I wanted to do it again, to escape this, the horrible force that chewed through my nerves like acid.