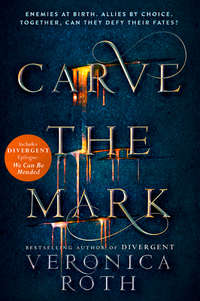

Carve the Mark

Yma and Lety were clutched together, weeping, Yma holding Lety back when she tried to lunge at me. Our eyes met as I pushed the pain and the inky darkness into her father’s body, and all I saw in her was hate.

Uzul screamed. He screamed for so long I grew numb to the sound.

“Stop!” he wailed eventually, and at Ryzek’s nod, I took my hands from his head. I stumbled back, seeing spots, and Vas’s hands pressed to my shoulders, steadying me.

“I tried to find the exiles,” Uzul said. His face was slick with sweat. “I wanted to flee Shotet, have a life free from this … tyranny. I heard they were on Zold, but the contact I found there fell through. They had nothing. So I gave up, I gave up.”

Lety was sobbing, but Yma Zetsyvis was still, her arm wrapped across her daughter’s chest.

“I believe you,” Ryzek said softly. “Your honesty is noted. Cyra will now administer your punishment.”

I willed the shadows in my body to drain out like water from a wrung rag. I willed the current to leave me and never return—blasphemy. But there was a limit to my will. At Ryzek’s stare the currentshadows spread, like he controlled them more than I did. And maybe he did.

I didn’t wait for his threats. I touched my skin to Uzul Zetsyvis’s until his screams filled all the empty spaces in my body, until Ryzek said to stop.

I SAW WHERE I was only dimly, the smooth step beneath my foot—bare now, I must have lost a shoe in the dining room—and the shifting fenzu light reflected in the floorboards and the webs of black coursing up and down my arms. My fingers looked crooked, like I had broken them, but it was just the angle at which they were all bent, digging into the air as they sometimes dug into my own palms.

I heard a muffled scream coming from somewhere in the belly of Noavek manor, and my first thought was of Eijeh Kereseth, though I had not heard his voice in months.

I had seen Eijeh only once since his arrival. It had been in passing, in a corridor near Ryzek’s office. He had been thin, and dead in the eyes. As a soldier muscled him past me, I had stared at the hollows above his collarbone, deep trenches now empty of flesh. Either Eijeh Kereseth had an iron will, or he really didn’t know how to wield his currentgift, just as he claimed. If I had to bet on one or the other, it would be the latter.

“Send for him,” Ryzek snapped at Vas. “This is what he’s for, after all.”

The top of my foot skimmed the dark wood. Vas, the only one who could touch me, was half carrying me back to my room.

“Send for who?” I mumbled, but I didn’t listen to the answer. A wave of agony enveloped me, and I thrashed in Vas’s grip as if that would help me escape it.

It didn’t work. Obviously.

He peeled his fingers away from my arms, letting me slide to the floor. I braced myself on hands and knees in my bedroom. A drop of sweat—or tears, it was hard to say—fell from my nose.

“Who—” I rasped. “Who was screaming?”

“Uzul Zetsyvis. Your gift has a lingering effect, evidently,” Vas replied.

I touched my forehead to the cool floor.

Uzul Zetsyvis had collected fenzu shells. He had showed me, once, the more colorful ones, pinned to a board in his office, labeled by harvest year. They were iridescent, multicolored, as if they held strands of the currentstream itself. He had touched them like they were the finest things in his house, which was bursting at the seams with wealth. A gentle man, and I … I had made him scream.

A while later—I didn’t know how long—the door opened again, and I saw Ryzek’s shoes, black and clean. I tried to sit up, but my arms and legs shook, so I had to settle for just turning my head to look at him. Hesitating in the hallway behind him was someone I recognized distantly, as if from a dream.

He was tall—almost as tall as my brother. And he stood like a soldier, straight-backed, like he knew himself. Despite that soldier’s posture, however, he was thin—gaunt, really, little shadows pooling under his cheekbones—and his face was again dappled with old bruises and cuts. There was a thin scar running along his jaw, ear to chin, and a white bandage wrapped around his right arm. A fresh mark, if I had to guess, still healing.

He lifted his gray eyes to mine. It was their wariness—his wariness—that made me remember who he was. Akos Kereseth, third child of the family Kereseth, now almost a grown man.

All the pain that had been building in me came rushing back at once, and I seized my head with both hands, stifling a cry. I could hardly see my brother through the haze of tears, but I tried to focus on his face, which was pale as a corpse.

There were rumors about me all throughout Shotet and Thuvhe, encouraged by Ryzek—and maybe those rumors had traveled all throughout the galaxy, since all mouths loved to chatter about the favored lines. They spoke of the agony my hands could bring, of an arm littered with kill marks from wrist to shoulder and back again, and of my mind, addled to the point of insanity. I was feared and loathed at the same time. But this version of me—this collapsing, whimpering girl—was not that person of rumor.

My face burned hot, from something other than pain: humiliation. No one was supposed to see me like this. How could Ryzek bring him here when he knew how I always felt, after … well, afterward?

I tried to choke back my anger so Ryzek wouldn’t hear it in my voice. “Why have you brought him here?”

“Let’s not delay this,” Ryzek said, and he beckoned Akos forward. They both drew closer to me, Akos’s right arm pulled close to his body, like he was trying to stay as far away from my brother as possible without disobeying him.

“Cyra, this is Akos Kereseth. Third child of the family Kereseth. Our”—Ryzek smirked—“faithful servant.”

He was referring, of course, to Akos’s fate, to die for our family. To die in service, as the Assembly feed had proclaimed two seasons ago. Akos’s mouth twisted at the reminder.

“Akos has a peculiar currentgift that I think will interest you,” Ryzek said.

He nodded to Akos, who crouched beside me, then extended his hand, palm up, for me to take.

I stared at it. I almost didn’t know what he meant by it, at first. Did he want me to hurt him? Why?

“Trust me,” Ryzek said. “You’ll like it.”

As I reached for Akos, the darkness spread beneath my skin like spilled ink. I touched my hand to his, and waited for his scream.

Instead, all the currentshadows ran backward and disappeared. And with them went my pain.

It was not like the remedy that I had swallowed earlier, which made me sick, at worst, and dulled all sensation, at best. It was like returning to the way I had been before my gift developed; no, even that had never been as quiet and as still as I felt now, with my hand on his.

“What is this?” I said to him.

His skin was rough and dry, like a pebble not quite smoothed by the tide. Yet there was some warmth in it. I stared at our joined hands.

“I interrupt the current.” His voice was surprisingly deep, but it cracked like it was supposed to at his age. “No matter what it does.”

“My sister’s gift is substantial, Kereseth,” Ryzek said. “But lately it has lost most of its usefulness because of how it incapacitates her. It seems to me that this is how you can best fulfill your fate.” He bent closer to Akos’s ear. “Of course, you should never forget who really runs this house.”

Akos didn’t move, though a look of revulsion passed over his face.

I sat back on my heels, careful to keep my palm on Akos’s, though I couldn’t look him in the eye. It was as if he had walked in on me while I was changing; he had seen more than I ever let people see.

When I stood, he stood with me. Though I was tall myself, I only came up to his nose.

“What are we supposed to do, hold hands everywhere we go?” I said. “What will people think?”

“They will think he is a servant,” Ryzek said. “Because that is what he is.”

Ryzek stepped toward me, lifting his hand. I recoiled, yanking my hand from Akos’s grasp, and flushing with black tendrils all over again.

“Do I detect ingratitude?” Ryzek asked. “Do you not appreciate the efforts I have made to ensure your comfort, what I am giving up by offering you our fated servant as a constant companion?”

“I do.” I had to be careful not to provoke him. The last thing I wanted was more of Ryzek’s memories replacing my own. “Thank you, Ryzek.”

“Of course.” Ryzek smiled. “Anything to keep my best general in prime condition.”

But he didn’t think of me as a general; I knew that. The soldiers called me “Ryzek’s Scourge,” the instrument of torment in his hand, and indeed, the way he looked at me was the same way he looked at an impressive weapon. I was just a blade to him.

I stayed still until Ryzek left, and then, when Akos and I were alone, I started pacing, from the desk to the foot of the bed, to the closed cabinets that held my clothes, back to the bed again. Only my family—and Vas—had been in this room. I didn’t like how Akos stared at everything, like he was leaving little fingerprints everywhere.

He frowned at me. “How long have you been living this way?”

“What way?” I said, more harshly than I meant to. All I could think about was how I must have looked when he saw me, cowering on the floor, streaked with tears and soaked with sweat, like some kind of wild animal.

His voice softened with pity. “Like this, keeping your suffering a secret.”

Pity, I knew, was just disrespect wrapped in kindness. I had to address it early, or it would grow unwieldy in time. My father had taught me that.

“I came into my gift when I had only lived eight seasons. To the great delight of my brother and father. We agreed that I would keep my pain private, for the good of the Noavek family. For the good of Shotet.”

Akos let out a little snort. Well, at least he was done with pity. That hadn’t taken long.

“Hold out your hand,” I said quietly. My mother had always talked quietly when she was angry. She said it made people listen. I didn’t have her light touch; I had all the subtlety of a fist to the face. But still, he listened, stretching out his hand with a resigned sigh, palm up, like he meant to relieve my pain.

I brought my right wrist to the inside of his, grabbed him under his shoulder with my left hand, and turned, sharply. It was like a dance—a shifted hand, a transfer of weight, and I was behind him, twisting his arm hard, forcing him to bend.

“I may be in pain, but I am not weak,” I whispered. He stayed still in my grasp, but I could feel the tension in his back and his arm. “You are convenient, but you are not necessary. Understand?”

I didn’t wait for a response. I released him, stepping back, my currentshadows returning with stinging pain that made my eyes water.

“Next door there’s a room with a bed in it,” I said. “Get out.”

After I heard him leave, I leaned into the bed frame, eyes closed. I didn’t want this; I didn’t want this at all.

I DIDN’T EXPECT AKOS Kereseth to return, not without being dragged. But he was at my door the next morning, a guard lingering a few paces behind him, and he had a large vial of purple-red liquid in hand.

“My lady,” he said, mocking. “I thought, since neither of us wants to maintain constant physical contact, you might try this. It’s the last of my stores.”

I straightened. When the pain was at its worst, I was just a collection of body parts, ankle and knee and elbow and spine, each working to pull me up straight. I pushed my tangled hair over one shoulder, suddenly aware of how strange I must look, still in my nightgown at noonday, a sleeve of armor around my left forearm.

“A painkiller?” I asked. “I’ve tried those. They either don’t work or they’re worse than the pain.”

“You’ve tried painkillers made from hushflower? In a country that doesn’t like to use it?” he asked me, eyebrows raised.

“Yes,” I replied, terse. “Othyrian medicines, the best available.”

“Othyrian medicines.” He clicked his tongue. “They may be the best for most people, but your problem isn’t what ‘most people’ need help with.”

“Pain is pain is pain.”

Still, he tapped my arm with the vial. “Try it. It may not get rid of your pain entirely, but it will take the edge off and it won’t have as many side effects.”

I narrowed one eye at him, then called for the guard standing in the hallway. She came at my urging, bobbing her head to me when she arrived in the doorway.

“Taste this, would you?” I said, pointing to the vial.

“You think I’m trying to poison you?” Akos said to me.

“I think it’s one of many possibilities.”

The guard took the vial, her eyes wide with fear.

“It’s fine, it’s not poison,” Akos said to her.

The guard swallowed some of the painkiller, wiping her mouth with the back of her hand. We all stood for a few seconds, waiting for something, anything, to happen. When she didn’t collapse, I took the vial from her, currentshadows surging to my fingers so they prickled and stung. She walked away as soon as I did, recoiling from me as she would have an Armored One.

The painkiller smelled malty and rotten. I gulped it down all at once, sure it would taste as disgusting as these potions usually did, but the flavor was floral and spicy. It coated my throat and pooled in my stomach, heavy.

“Should take a few minutes to set in,” he said. “You wear that thing to sleep?” He gestured to the sheath of armor around my arm. It covered me from wrist to elbow, made from the skin of an Armored One. It was scratched in places from the swipes of sharpened blades. I took it off only to bathe. “Were you expecting an attack?”

“No.” I thrust the empty vial back into his hands.

“It covers your kill marks.” He furrowed his brow. “Why would Ryzek’s Scourge want to hide her marks?”

“Don’t call me that.” I felt pressure inside my head, like someone was pushing my temples from both sides. “Never call me that.”

A cold feeling was spreading through my body, out from my center, like my blood was turning to ice. At first I thought it was just anger, but it was too physical for that—too … painless. When I looked at my arms, the shadow-stains were still there, under my skin, but they were languid.

“The painkiller worked, didn’t it,” he said.

The pain was still there, aching and burning wherever the currentshadows traveled, but it was easier to ignore. And though I was starting to feel a little drowsy, too, I didn’t mind it. Maybe I would finally get a good night’s sleep.

“Somewhat,” I admitted.

“Good,” he said. “Because I have a deal to offer you, and it relies on the painkiller being useful to you.”

“A deal?” I said. “You think you’re in a position to make deals with me?”

“Yeah, I do,” he said. “As much as you insist you don’t need my help with your pain, you want it, I know you do. And you can either try to batter me into submission to get it, or you can treat me like a person, listen to what I have to say, and maybe get my help easily. Your choice, of course, my lady.”

It was easier to think when his eyes weren’t bearing down on mine, so I stared at the lines of light coming through the window coverings, showing the city in strips. Beyond the fence that kept Noavek manor separate, people would be out walking the streets, enjoying the warmth, dust floating all around them because the earthen streets were dry.

I had begun my acquaintance with Akos in a position of weakness—literally, huddled on the floor at his feet. And I had tried to force my way back to a place of strength, but it wasn’t working; I couldn’t erase what was so obvious to anyone who looked at me: I was covered in currentshadows, and the longer I suffered because of them, the more difficult it was for me to live a life that was worth anything to me. Maybe this was my best option.

“I’ll listen,” I said.

“Okay.” He brought a hand to his head, touching his hair. It was brown, and clearly thick, judging by how his fingers knotted in it. “Last night, that … maneuver you did. You know how to fight.”

“That,” I said, “is an understatement.”

“Would you teach me, if I asked you?”

“Why? So you can keep insulting me? So you can try—and fail—to kill my brother?”

“You just assume I want to kill him?”

“Don’t you?”

He paused. “I want to get my brother home.” He spoke each word with care. “And in order to do that, in order to survive here, I have to be able to fight.”

I didn’t know what it was to love a brother that much, not anymore. And from what I had seen of Eijeh—a flimsy wreck of a person—he didn’t seem worthy of the effort. But Akos, with his soldier’s posture and his still hands, seemed certain.

“You don’t know how to fight already?” I said. “Why did Ryzek send you to my cousin Vakrez for two seasons, if not to teach you competency?”

“I’m competent. I want to be good.”

I crossed my arms. “You haven’t gotten to the part of this deal that benefits me.”

“In exchange for your instruction, I could teach you to make that painkiller you just drank,” he said. “You wouldn’t have to rely on me. Or anyone else.”

It was like he knew me, knew the one thing he could say that would tempt me the most. It wasn’t relief from pain that I wanted above all, but self-reliance. And he was offering it to me in a glass vial, in a hushflower potion.

“All right,” I said. “I’ll do it.”

Soon after that I led him down the hall, to a small room at the end with a locked door. This wing of Noavek manor wasn’t updated; the locks still took keys instead of opening at a touch or the prick of a finger, like the gene locks that opened the rooms where Ryzek spent most of his time. I fished the key out of my pocket—I had put on real clothes, loose pants and a sweater.

The room held a long countertop with shelves above and below it, packed with vials, beakers, knives, spoons, and cutting boards, and a long line of white jars marked with the Shotet symbols for iceflowers—we kept a small store of them, even hushflower, though Thuvhe had not exported any goods to Shotet in over twenty seasons, so we had to import it illegally using a third party—as well as other ingredients scavenged from across the galaxy. Pots, all a shade of warm orange-red metal, hung from a rack above the burners on the right, the largest bigger than my head and the smallest, the size of my hand.

Akos took one of the larger pots down and set it on a burner.

“Why did you learn to fight, if you could hurt with a touch?” he said. He filled a beaker with water from the spout in the wall, and dumped it in the pot. Then he lit the burner beneath it and took out a cutting board and a knife.

“It’s part of every Shotet education. We begin as children.” I hesitated for a moment before adding, “But I continued because I enjoyed it.”

“You have hushflower here?” he said, scanning the jars with his finger.

“Top right,” I said.

“But the Shotet don’t use it.”

“‘The Shotet’ don’t,” I said stiffly. “We’re the exception. We have everything here. Gloves are under the burners.”

He snorted a little. “Well, Exceptional One, you should find a way to get more. We’ll be needing it.”

“All right.” I waited a beat before asking, “No one in army training taught you to read?”

I had assumed that my cousin Vakrez had taught him more than competent fighting skills. Written language, for example. The “revelatory tongue” referred only to spoken language, not written—we all had to learn Shotet characters.

“They didn’t care about things like that,” he said. “They said ‘go’ and I went. They said ‘stop’ and I did. That was all.”

“A soft Thuvhesit boy shouldn’t complain about being made into a hard Shotet man,” I said.

“I can’t change into a Shotet,” he said. “I am Thuvhesit, and will always be.”

“That you are speaking to me in Shotet right now suggests otherwise.”

“That I’m speaking Shotet right now is a quirk of genetics,” he snapped. “Nothing more.”

I didn’t bother to argue with him. I felt certain he would change his mind, in time.

Akos reached into the jar of hushflower and took one of the blossoms out with his bare fingers. He broke a piece off one of the petals and put it in his mouth. I was too stunned to move. That amount of iceflower at that level of potency should have knocked him out instantly. He swallowed, closed his eyes for a moment, then turned back to the cutting board.

“You’re immune to them, too,” I said. “Like my currentgift.”

“No,” he said. “But their effect is not as strong, for me.”

I wondered how he had discovered that.

He turned the hushflower blossom over and pressed the flat of the blade to the place where all the petals joined. The flower broke apart, separating petal by petal. He ran the tip of the knife down the center of each petal, and they uncurled, one by one, flattening. It was like magic.

I watched him as the potion bubbled, first red with hushflower, then orange when he added the honeyed saltfruit, and brown when the sendes stalks went in, stalks only, no leaves. A dusting of jealousy powder and the whole concoction turned red again, which was nonsense, impossible. He moved the mixture to the next burner to cool, and turned toward me.

“It’s a complex art,” he said, waving a hand to encompass the vials, beakers, iceflowers, pots, everything. “Particularly the painkiller, because it uses hushflower. Prepare one element incorrectly and you could poison yourself. I hope you know how to be precise as well as brutal.”

He felt the side of the pot with the tip of his finger, just a light touch. I could not help but admire his quick movement, jerking his hand back right when the heat became too much, muscles coiling. I could already tell what school of combat he had trained in: zivatahak, school of the heart.

“You assume I’m brutal because that’s what you’ve heard,” I said. “Well, what about what I’ve heard about you? Are you thin-skinned, a coward, a fool?”

“You’re a Noavek,” he said stubbornly, folding his arms. “Brutality is in your blood.”

“I didn’t choose the blood that runs in my veins,” I replied. “Any more than you chose your fate. You and I, we’ve become what we were made to become.”

I knocked the back of my wrist against the door frame, so armor hit wood, as I left.

The next morning I woke when the painkiller wore off, just after sunrise, when the light was pale. I got out of bed the way I usually did, in fits and starts, pausing to take deep breaths like an old woman. I dressed in my training clothes, which were made of synthetic fabric from Tepes, light but loose. No one knew how to keep the body cool like the Tepessar people, whose planet was so hot no person had ever walked its surface bare-skinned.

I leaned my forehead against a wall as I braided my hair, eyes shut, fingers feeling for every strand. I didn’t brush my thick dark hair anymore, at least not the way I had as a child, so meticulous, hoping each stroke of the bristles would coax it into perfect curls. Pain had stripped me of such indulgences.

When I finished, I took a small currentblade—turned off, so the dark tendrils of current wouldn’t wrap around the sharpened metal—into the apothecary chamber down the hall where Akos had moved his bed, stood over him, and pressed the blade to his throat.

His eyes opened, then widened. He thrashed, but when I pushed harder into his skin, he went still. I smirked at him.