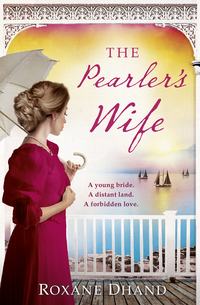

The Pearler’s Wife: A gripping historical novel of forbidden love, family secrets and a lost moment in history

Beads of sweat trickled down her worsted-clad spine, her feet protested in pools of deliquescent silk stocking, and the blood pounded hot in her cheeks. She folded her napkin carefully on her plate. ‘Would you mind very much if I give it a miss, Mrs Wallace? I don’t understand bridge at all well and am so hot in these suffocating clothes, I would prefer to take a turn on deck, to try to cool down a little before bed.’

‘You must not do that alone, Maisie. People will think you are fast. You must remember your position, as an engaged woman.’ She accented the word, giving Mr Smalley a sharp look. ‘I will forgo my game of bridge and accompany you, to safeguard your reputation. Western Australia has a very small English community and there will be gossip if you gad about by yourself. We must get you out of the habit quick smart.’

Maisie looked down at her hands. ‘No,’ she said quietly to no-one in particular but primarily to herself. She had put a smile on her face all evening until her muscles ached from the effort and she felt ill-disposed towards the loathsome Mr Smalley and his proposed game of cards.

Mrs Wallace blinked several times, very fast. ‘I beg your pardon?’

‘I may be engaged to be married but I am not about to enter a religious order and take my vows. I am quite able to take a walk by myself.’

‘Don’t be cheeky, dear. Have you no sense of propriety?’

‘I’m sorry,’ she said. ‘I shouldn’t have said that.’ Out loud.

Mrs Wallace gave her a nod. ‘Good. Now come along. I thought you wanted a stroll.’

The divide between decks was no more than a couple of wooden gates, but everyone was aware of their function: to keep the three classes separate and in their proper places.

That evening, Mrs Wallace had liquid courage pumping in her veins. ‘What would you say, Maisie, if we were to take a turn through third class?’ Her speech was a little slurred.

Have we swapped roles and I have now become the responsible adult in charge of what is right and wrong? She put a hand on Mrs Wallace’s arm. ‘I’m not sure that we are supposed to. Trespassing between the decks is not permitted. The captain was very clear on that point. Do you not remember that he said so, at dinner on the first night?’

‘Of course I do, but he didn’t mean people like us, Maisie. These third-class folk know their place – they have had centuries of observance to remind them. The comment was made for them.’

‘They weren’t at our dinner, Mrs Wallace.’

‘Don’t split hairs, dear.’ Mrs Wallace clicked open the gate that accessed the lower deck and clattered down a flight of narrow wooden stairs, with Maisie a reluctant accomplice.

The night was overcast, but every now and then the clouds parted and moonlight filtered palely across the deck. Maisie saw they weren’t the only trespassers from the upper deck: a man with a sun-mottled complexion and an excess of yellow teeth stood at the bottom of the steps, his back braced against a deck lamp. She recognised him from the first-class lounge, wearing what her mother would describe as ‘new-money clothes’, smoking a slim cigar and, by all appearances, having helped himself generously to the post-prandial drinks tray. He steadied himself on the handrail, his bony fingers clutching the smooth, rounded wood like an eagle perched on a branch.

‘Is that you, Mr Farmount?’ Puffed from the stairs, Mrs Wallace dragged air into her lungs and blinked several times.

He didn’t bow. Maisie suspected that the gesture would have toppled him over.

‘Ladies. What brings you down to the third-class deck?’

‘Stretching our legs,’ Mrs Wallace replied. ‘And yourself?’

‘Checking on my off-duty divers over there.’ He took a puff of his cigar and let a cloud of dense, blue-tinged smoke swirl up out of his open mouth.

‘What do they dive for?’ Maisie had romantic visions of Spanish galleons and buried treasure.

‘Pearl shell. They are going out to Australia to settle a bet.’ He slid his eyes in her direction and then looked away again.

‘What sort of bet?’ Maisie followed the line of his arm. She half-expected his fingernails to be filed sharp, like claws.

‘Maybe to prove a point would be a better way of describing it.’

‘I’m not certain I understand.’

Mr Farmount swayed towards them, exhaling sour gouts of cigar-tainted breath.

‘My boys are going to show that the pearl industry is better served by white divers.’

When Maisie shook her head, none the wiser, Farmount looked at her as if she were stupid. He dabbed at his face with a freckled hand. ‘The industry imports a coloured workforce. Japs, mostly. Australia wants to kick them out.’

‘And the English divers are going to help do this? To put them out of their jobs?’

‘Precisely. They’re no longer wanted.’

Maisie looked over at the group of ten or so men who were sitting under the deck lamps, playing cards for a pile of matchsticks. ‘That doesn’t sound fair.’

Mr Farmount picked a strand of tobacco off his tooth. ‘That’s not the point. The English boys are what the government wants. They’ll give those imported fellers a run for their money.’

‘Have they experience of diving for pearl shell?’

Mr Farmount waved his hand in a dismissive gesture. ‘Details, my dear. Diving is diving when all is said and done. It doesn’t matter at all what they are diving for.’

Maisie glanced across for a second time at the group of card players. One of the men, his cards held close to his chest in a neat fan, looked up from his hand and locked eyes with her. His stare didn’t waver. With legs crossed, the stub of a cigarette glowing between his teeth, she saw he was dark-haired and lean, like a panther she’d once seen in a zoo. His fingers tightened on the cards and she sensed his concentration on her face, the animalistic coiling of a predator preparing to pounce on his prey. She bowed her head for a moment then looked again at his face, a vague, undefinable sensation stirring her stomach.

Without warning, it began to rain gentle, warm drops from the dark night sky.

Mrs Wallace turned away from Mr Farmount. ‘Take my arm, dear. It’s high time we went back up and got you off to bed.’

Maisie cupped her hand under Mrs Wallace’s elbow and steered her back towards the dark flight of stairs. By the bottom step, the lamp cast a little patch of yellow light. She placed her foot in the centre of it and, for a reason she could not explain, turned back towards the card players.

Chapter 2

FEBRUARY WAS AN UGLY month in Buccaneer Bay.

The pearling magnates and town bureaucrats were crammed into a smoke-filled bar. Well oiled with drink and shiny with sweat, they nodded towards their civic leader, impatient to hear his message; it was stiflingly hot and they were not happy to have their drinking interrupted for long. It was going round that someone had set up a game later on in Asia Place and there would be the usual female attractions afterwards. The windows had been flung open but there was scant relief from the heat and humidity. One or two ran surreptitious fingers round the inside of their collars and slacked off the studded moorings. Standards of dress in the Bay had to be upheld even among groups of men. It was not the done thing to breach etiquette.

‘Gentlemen,’ the mayor began, standing atop a chair and waving his glass in a wide, embracing circle. Blair Montague was top dog in Buccaneer Bay, not only mayor but also acting president of the Pearlers’ Association. He divided his time buying and selling pearls in Asia and Europe and overseeing his business interests. A sheepdog herding its flock, his voice was hard and flat. ‘We have a delicate situation on our hands. On the very eve of a brand-new pearling season in Buccaneer Bay, our Australian government has issued a directive: we must expel all non-white labour from our fleets.’

He pulled a folded paper from his inside jacket pocket. ‘I quote what is written: White Australia will no longer tolerate the yellow-faced worker on its pearling fleet. The Japanese, the Malays and the Koepangers must go home.’

He looked down at the sweaty faces. ‘It seems our Asiatics are no match for the white-skinned Navy diver. To prove the government is right, we are to welcome a handful of English divers into the bosom of our community and employ them on our boats. There is to be no discussion.’

He watched as his words hit them as hard as a blow. They all knew what this would mean to their balance sheets.

Blair nodded. ‘I agree with your sentiments, but these men are already on their way and there is nothing we can do to stop the process. I have had to spread them among us and we will have to bear the cost of their passage. When you do the sums you will see that these flash divers will cost us five times as much as we are paying our indentured crews. They will be a cause of discontent and trouble among our workforce and the means of huge financial losses for us.’

He produced another folded paper from his pocket on which he had recorded names and details in neat columns. He had chosen wisely. The men he had selected were rugged entrepreneurs – tough, demanding individuals who had made their pearl-shell fortunes through hard-nosed dealings in a perilous industry.

Blair got down from his chair and pushed it back against the wall with his foot, his legs stiff from standing. He scanned the room and found his man amid the town’s grumbling elite, a faint smile softening his angular face. He nodded towards the door. ‘Join me outside for a jar?’

Blair found a vacant table on the narrow verandah and motioned his guest to sit. A steward appeared, his drinks tray tucked under his arm, a foot soldier at ease, awaiting orders.

‘Bring Captain Sinclair a single malt with some Apollinaris water. I’ll have my usual.’

Maitland Sinclair looked Blair straight in the eye. ‘How long have you known about this?’

Blair lounged back in a cane chair and crossed his legs. ‘Dear me,’ he said in a gravely mocking voice. ‘Did I forget to consult you?’ He reached over to the next table and stretched his fingers towards a newspaper threaded on a hinged wooden stick. Blair never sweated. There were no half-moons of damp fabric under his arms. His face and clothes were wrinkle-free. He tapped the headline with a long lean finger. ‘Look at that. Captain Scott’s reached the South Pole.’ The newspaper was dated January 1912; it was six weeks old. Something else further down caught his eye. He smoothed out the page with the back of his hand. ‘What’s the surname of that overbred English girl you’re bringing out here? Father’s a judge, didn’t you tell me?’

Maitland squinted at him, a pipe hanging from his bottom lip. The sullen line of his mouth relaxed. ‘Good memory. Judge George Porter.’

‘Seems he’s trying that big Jew murder in London.’

‘Let’s see.’ Maitland leaned forward and traced the words under the photograph with his finger. ‘Yes, that’s him.’ He flicked the photograph of Captain Scott and his sled with his nail. ‘Would be nice to escape from this bloody heat and feel the chill for once. Wet’s hardly half-through.’ He wiped his brow with a white silk handkerchief as a streak of lightning flared overhead and silhouetted the lighthouse against the stormy sky. Seconds later, a blast of thunder muffled the blow of his fist hitting the table.

‘Why didn’t you tell me about the English divers?’

‘Look, Mait, I didn’t want to tell you about the government’s directive until I’d had time to think.’ Blair pulled the paper off the wooden stick and rolled it up like a cosh. ‘This white diving thing’s a bugger.’

Maitland shook his head.

‘Stop sulking, Mait. You now know as much as I do. All you’ve got to do is help me make sure this thing fails.’

The steward arrived with the drinks and temporarily cut the conversation. Maitland stretched over to take his drink off the tray, took a sip and dabbed his lips with his handkerchief.

Blair drained his glass in two gulps without any pretence at restraint and thrust it back towards the steward. ‘Another.’

The steward nodded. When he left the table, Maitland leaned in slightly and dropped his voice to a whisper. ‘What do you want me to do?’

‘You’ve got to get everyone on board with this. The local press, all them in there.’ Blair waved his hand at the bar. ‘Even the Japanese doctor.’

‘Yes. He’s popular. He’s got gumption.’

Blair narrowed his eyes. ‘He’s got ambition. That’s different. He showboated himself through that hospital-building project. He’s a crowd manipulator.’

‘Precisely.’

Blair squeezed Maitland’s arm, his mouth thin with resolution. ‘This is up to you, Mait. I’m doing the behind-the-scenes work but now I’m handing you the rope to strangle the venture. Get all our current divers on board. Offer them advances on their pay, better percentage rewards on the shell and pearls they bring up – whatever it takes. Get the tenders and shell-openers on side. Talk to Doctor Shin and offer him a donation for his hospital but make sure he’s in our pocket. All you’ve got to do, Mait, is wind the rope of failure so tightly round those divers’ white necks that they lynch themselves. Then I can get on with flogging my pearls and turning a decent profit, and you can get on with buying yourself some class. Do we understand each other?’

Maitland held his gaze. ‘I’ve always been your man, haven’t I?’

Blair slapped his hands together, as if he were shutting a book. ‘As I have been yours. We must work together, Mait, and stamp on this bloody notion before we both lose everything we’ve built up. When those divers set foot on our jetty next month, they’re already condemned men.’

A few weeks after the mayor dropped his bombshell, Maitland Sinclair sat at the scarred wooden desk in his office and scowled at the wall. Blair’s words had been giving him headaches for what seemed like forever. The venture had to fail, but on paper he needed it to look above board. It was hot in the packing shed and he was already sweating through his shirt. He had risen early, and on his way to work had dropped by the Black Dog Hotel and eaten a substantial breakfast of fried steak, salted bacon and tinned tomatoes. There were no fresh eggs, which had made him cross. The hotel had run out and was, the Japanese proprietor apologised profusely, waiting for the next steamship from Port Fremantle to top up its larder. Maitland had sworn freely and pushed over the table, refusing to pay the bill.

Now he glanced through the open door onto the mudflats and allowed himself a moment’s distraction. His hands coiled into fists. The girl would arrive on the coastal steamer all too soon from Port Fremantle. He had cabled the steamship, and once in the Bay, she would have a bed to sleep in. What else was there to do? He shook his head to clear the concern. She was a means to an end.

Back to work. He was tallying up the costs he had incurred to take on the white diver, William Cooper. He knew nothing about him, other than he was said to be the Navy’s top man. By the time Maitland had learned that the diver was being dumped on him, there had been no time to write chummy get-to-know-you letters, and now the bloke was about to arrive. Blair was right, though. Putting white divers on the pearling luggers made no financial sense. He had personally had to pay the cost of two third-class passages from England: Cooper had insisted on bringing his own tender with him. Adding in half-wages during the two-month journey for both, he had forked out £24 just to get them to Buccaneer Bay – and he had no idea whether they would be any good at bringing up shell. It was starting to look like a very expensive exercise. He put down his pen and tamped down the tobacco in his pipe. A blob of nicotine dripped from the stem and flared onto his white trousers. He swore under his breath and hurled it to the floor.

What he did know was that Cooper would have to collect a hell of a lot of shell for Maitland to recover his expenses. He had more than a slight suspicion that he would be out of pocket, but if it meant that the government’s white-diver experiment failed, then he supposed a few quid gambled on a good cause was a reasonable investment. He would write the money off against his profits somewhere else. After all, the whole point of living in the back of beyond was not having to play by the rules. Not one official had ever bothered to come to the Bay and police what was going on. And if he managed to pick up a pearl or two along the way, well, he would make a generous donation to the Pearlers’ Association and buy himself a bit more leverage.

He swivelled on his chair and looked out at the murky water. Along the foreshore, the luggers were lined up, hauled up high on the beach by their crews to await maintenance and refits for the start of the new season. The thirty-foot ketch-rigged vessels looked spacious enough on the flat yellow sand, but once the boats were loaded up for the season there was barely room for a man to stand.

He pushed himself up from his chair and shuffled out of his office, lumbering round the back of the building, the momentary shade softening his mood. He picked his way along the crunchy shell path that snaked towards the lighthouse where the track petered out. Towering stacks of empty oil drums and wooden pallets lined his route. The stench of ozone, fish and stale urine was strong as he heaved himself up the steps towards the loading stage of his packing shed.

He heard the familiar sound of tomahawk striking shell from inside the large, corrugated-iron shed. At the entrance, it took him a few moments to adjust from the bright sunlight to the gloom of the interior. At the far end of the shed he saw a huge pile of pearl shell that two Manilamen were processing, squatting back on their haunches, sarongs tucked up between their legs as they sorted the shell into shallow floor bins according to size and condition. The gold-lipped shell sparkled in the light from the open doors as they tossed it through the air. A third man was stencilling letters onto a wooden crate destined for New York, where Maitland sold the majority of his shell to the button trade. Another man, his back to the door, sat cross-legged beside the bin containing the largest shell. Maitland watched him pick out a shell and hold it up, eyeing himself in the shining surface. He stroked the smooth surface with the long arc of his finger and then held it up against his cheek, caressing it like a lover. Something about the intimate gesture rooted Maitland to the spot. He glanced around. When he was sure they were alone, he spoke rapidly in Malay and the other man turned, the shell still pressed to his cheek. They held each other’s gaze and Maitland flicked his head towards the door. The Malay threw the shell back into the bin and scrambled to his feet.

‘I go your office,’ he stammered in English.

Maitland strolled out into the sunshine, a sly smile tugging at one corner of his mouth. The Malay followed behind, dragging his feet in the dust.

Chapter 3

THE MORNING WAS SPARKLING blue as the SS Oceanic bumped onto its moorings in Port Fremantle. Soon, Maisie’s six-week voyage from England would be a memory of deck tennis, quoits, concerts and endless meals dodging Mr Smalley’s groping fingers. On deck, a dozen Englishmen gathered by the rail. They stood quietly, facing away from Maisie, looking towards the rotted jetty stumps. Clothed in heavy dark wool suits with white celluloid collars that looked stiff and unfamiliar, most were smoking. One of the men wore his trousers short to his ankles, his fancy patterned socks on display above the toe-pinching shoes. Maisie, sitting on a deckchair next to Mrs Wallace, flexed her swollen feet in sympathy.

A small engine-driven tugboat bounced alongside the ship, jammed with men waving pale-jacketed arms in the air. They were clutching notebooks, some with cameras slung on straps round their necks. The second officer had told Maisie that newspaper reporters would come aboard that morning to the first-class deck and would, regrettably, delay their disembarkation by an hour or two.

A brass band was blaring ‘Land of Hope and Glory’ from the quayside. Maisie caught the whiff of excitement that thrummed through the crowd and leaned forward in her chair on the upper deck to watch the scene. Shading her eyes from the bright sunlight, she saw that the first of the newspapermen had climbed up the ladder and was shaking the hand of Mr Farmount. By the time the tugboat’s passengers were fully on board, Mr Farmount had the twelve Englishmen corralled and a photographer was arranging them, a few seated and the surplus standing behind. There they remained under the unrelenting sun, eyes on the camera box for some time, red patches blooming on tender exposed skin.

Maisie shaded her eyes from the blinding sun and considered for a moment retreating into the shade, until she saw that Mr Farmount had moved closer to the press party.

She patted Mrs Wallace’s arm. ‘I think Mr Farmount is about to make a speech.’

‘Of course he is, dear. It’s why the newspaper people have come. Now pipe down or we shan’t be able to hear what he says.’

Maisie pressed her lips together, her cheeks burning.

Farmount consulted his notes and thrust his redundant hand in a pocket. Maisie saw that he was nervous; his face was spotted with perspiration and his other hand was trembling. He straightened his jacket and cleared his throat.

‘Thank you all for coming,’ he began, his voice just audible against the brass band’s enthusiasm. ‘The gentlemen to my left are all ex-Royal Navy Divers. I am here as their ambassador, and also to represent Siegfried and Hammond – the largest manufacturer of diving apparatus in the world. The company is the sole contractor to the British Admiralty and the Crown Agents for the Colonial and Indian Office.’ He broke off and wiped a handkerchief across his brow.

‘Their arrival on Australian soil marks the end of an era. Our divers are here to prove, once and for all, the superiority of the Britisher over the Asiatic.’ Farmount looked up, his nerves seemingly forgotten. ‘We cannot allow one of Australia’s primary industries to be dominated by a bunch of brown-skinned foreigners! Let the Japanese, Malays and Koepangers take heed. Their stronghold over the pearling industry is about to end, and these men –’ He waved a freckly paw at the sweating, wool-clad group. ‘These men, gentlemen of the press, are the men to end it.’

His fervour ignited the crowd. Amid a flurry of enthusiastic applause, a spiky-haired reporter thrust up his hand and shouted, ‘Mr Farmount! Ray Jones, Perth Advertiser. How long do you think it will take to drive the coloured fellers out?’

Farmount glanced sideways and nodded at the divers. ‘We’ve settled on a year to do the job, but we anticipate that it won’t take that long.’

‘Well said!’ a voice yelled from the crowd.

Maisie moved in her chair, looking from Mrs Wallace to Mr Farmount and back again. She knew so little about Australia – there had been no time to research – but she did know that this felt wrong.

‘Surely they should show more respect towards the men they are trying to replace,’ she said, not knowing anything about the white dominance of the coloured population. Mrs Wallace, padded in purple gingham, was nodding vigorously and banging her cotton-gloved fingers together in enthusiastic support of Mr Farmount’s speech.

Another hand shot up. ‘Pete Ramsey, Fremantle Chronicle. Can I get the names of all these brave English blokes, sir?’

Mr Farmount turned to the group and named the twelve men in turn, the last of whom was introduced as William Cooper, the most experienced diver in the team.

‘Can we get a few words, sir?’

Craning forward for a better view, Maisie recognised the man who had pushed to the front as the panther from the card game. His hair was as black as coal and even with the sun on his face, his eyes were dark and proud. She thought again of a sleek cat, crouching in the long grass, prey between its claws, and shrank back, her heart banging against her ribcage. Its excessive beating seemed to throw her balance and she felt as if she might faint.