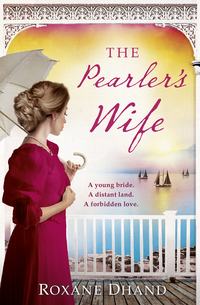

The Pearler’s Wife: A gripping historical novel of forbidden love, family secrets and a lost moment in history

With one arm draped around the diver’s neck, Mr Farmount slicked back his brilliantined hair with his free hand and wiped the excess grease down the side of his trousers. ‘William Cooper is the British Royal Navy’s finest diver. He has pioneered the use of my company’s engine-driven air compressor on his deep-sea dives, which will further prove that the day of the darky hand-pump deck-boy is done! We have brought this wonder machine with us and will use it to great effect on the luggers in Buccaneer Bay. We will show you all just what English manufactured equipment and the white diver can do.’

William Cooper stepped forward and shook the hair out of his eyes, exuding the casual assurance of someone who was used to the limelight.

Maisie fiddled with her gloves. ‘Have you heard of that diver William Cooper, Mrs Wallace?’

Mrs Wallace wedged her frame deeper into her chair and smoothed her dress over her bosom. ‘Do you not read the newspaper, Maisie?’

Maisie opened her mouth and closed it again. She knew if she were patient there would be more. Mrs Wallace was like a bottle of beer – once shaken up and the cap released, the contents couldn’t help but bubble out.

‘Mr Farmount told me he’s one of the Admiralty’s top operatives and has dived throughout the Mediterranean, wresting lost treasure from sunken ships. He’s unmarried – but has a keen eye for the ladies – and is reputed to be as tough as kangaroo meat, which is why he was wanted for this exercise. Now do be quiet, Maisie, dear. He’s going to say something.’

William Cooper flashed a brilliant smile at the reporters, and shouted to make himself heard over the music. ‘It is true. It is absolutely true what Mr Farmount has said. We are all British Royal Navy trained, and the depths in Buccaneer Bay are shallow compared to the depths we are used to. We have been given a challenge, and frankly, we can’t wait to pick up the gauntlet that has been thrown down. We want to get started right away and prove that the faith the Australian government has placed in us is not misguided.’

‘Hear! Hear!’ Mrs Wallace boomed. ‘Hear! Hear!’

Maisie wore her confusion on her face. ‘Mrs Wallace, I’m not sure I understand. I mean, just because these men are white, will they really be able to do it better than the men who have been doing it for years?’

Mrs Wallace removed her spectacles, her expression turning serious. ‘Maisie, you have a lot to learn, just as I did when I first came out here. The Australian government finds the reality of a coloured workforce unpalatable and is keen to seek a viable alternative. These English divers represent the answer to everyone’s prayers. Your future husband will be thinking these exact same thoughts and I’m sure that, as his wife, you will realise this soon enough when you are trying to staff a house with Japs, Malays and Binghis.’

‘Binghis?’

‘Aborigines. The Indigenous population. The average black fellow is reasonably honest until he takes a fancy to your gin bottle, at which point he will most likely turn into a mad savage. He could come at you with a tomahawk!’

Maisie tried not to betray her anxiety. ‘I thought that was what they used in the Americas.’

Mrs Wallace clicked her tongue. ‘Keep your smart comments to yourself, Maisie, until you know more about what you are saying. The Australian nation needs protection from these people and the Asian hordes invading in their droves from the north. All those Japanese and Malays – it simply can’t go on. Australia is a vulnerable island, Maisie. It is quite right that we try to keep our drawbridge up.’

Since that evening weeks ago, when the girl had come down to C Deck, William Cooper had been unable to put her out of his mind.

After that, sitting in the dark, night after night, he had looked up from his hand of cards and stretched his neck towards the first-class promenade deck.

He’d seen her for the very first time at the lifeboat drill. Even now, at the end of the voyage, that still bothered him. The SS Oceanic had been at sea for twenty-four hours before the passengers were shown what to do if the ship went down. Perhaps it was because he knew the sea that he found such negligence unfathomable. Cold, black water was no-one’s friend. It wouldn’t answer your cries for help or buoy you up when you knew you were sinking. He knew to respect the sea; everyone who earned his living from it did.

A good two hours had passed since the pressmen left the ship.

He leaned back against the metal chair, feeling the push of a bolt head against his spine. It was hot, holding the full day’s heat. He shifted a little to the side, easing his weight off his back, and let his hands drop loose by his sides.

Seeing her today on the deck listening to his speech, he’d felt like he was talking to her. Explaining why he’d come to Australia. He’d watched her draw in a breath, though, a cloud coming over her face at something he’d said. She pursed her lips and narrowed her eyes slightly, a frown appearing over the bridge of her nose.

William Cooper wondered where she was going. Was this her final stop? What would he say to her if ever they were to meet? What would her voice sound like? Would she even notice him?

His shirt stuck in damp patches to his back.

Maisie picked at the rumpled fabric on the chair’s armrest in the first-class lounge. ‘I know we change ships here in Port Fremantle, Mrs Wallace, but shall we move onto the coastal steamer tonight?’

‘Goodness no, dear. We shall stay in a hotel for a few days to gather our strength for the return to the north-west coast. I’m not quite sure if the coastal steamer even works on an exact timetable. Here we shall be ladies of leisure.’

Maisie dabbed at her face with the side of her hand. Although the portholes had been thrown wide open, the lounge was boiling hot and she was gently cooking inside her English wool travelling suit. She had already removed the long-line jacket but was still buttoned up to the neck in a silk blouse and tie. She parted her legs under the floor-length skirt and tried to subtly flap the fabric.

‘Haven’t we done that for six weeks already on this ship?’

‘Don’t be in too great a hurry to embrace your new life, Maisie. It might not be an exact replica of your home in England. Just make the most of your time at Port Fremantle and enjoy the cooler weather. And for goodness’ sake, dear, do stop fidgeting. If you’re that hot, go back up on deck and perhaps you’ll catch a bit of a breeze.’

It was just as hot on deck.

The sun had burned the sky to white. Maisie paused at the door of the lounge, studying him before he saw her. William Cooper was sitting on a chair, on the exact spot he’d made his address earlier on. His feet were dangling over the rail, eyes fixed on something in the water, his concentration absolute. He had taken off his jacket and rolled up his shirtsleeves. His fingers, she noticed, were long and still by his sides.

Maisie stepped back into the shade and slid into a deckchair. She dropped her bag on the deck, took out her book and tried to concentrate on the words. She could see him out of the corner of her eye, his foot swinging back and forth, rhythmic. She fanned the book wide and leaned her forehead against the smooth paper.

A hot hand clamped down on her shoulder and squashed her mouth against the page. Her throat went tight with alarm.

‘Miss Porter!’ Mr Smalley boomed. ‘I didn’t mean to startle you. The purser says we’ll be getting off soon, so I said I would come to fetch you.’

Maisie scrambled to her feet and knocked over her bag, the contents skittering across the deck. ‘Thank you, Mr Smalley. I’ll be there in a moment. Just let me …’ She fluttered a hand at the scattered items. Smalley had the grace to look slightly embarrassed before he toddled off.

William Cooper glanced sideways and flicked a strand of hair from his eyes. He stood up, scraping his chair across the polished wood, and looked directly at her. Maisie felt perspiration collecting in beads on her forehead.

He stood motionless for a second, then bent to gather her fallen items from the deck, trapping them against his side with his arm. She stared at him, confusion rearing up in her chest like a horse.

‘Forgive me,’ she said, her cheeks stained with embarrassment. ‘I am so sorry to have disturbed your reverie.’

He turned back and laughed, the skin twitching the soft edges of his lips.

‘You’re forgiven,’ he said, placing her treasures on a table. ‘For disturbing my “reverie”.’

Maisie scrabbled her possessions back into her bag, her hands trembling as she wished she could claw the words back. Why on earth did I say reverie? I sound like a nincompoop.

When she moved to rejoin Mrs Wallace in the downstairs lounge, Maisie found that her legs were rather wonky.

It took a long time to disembark, but eventually, their paperwork secured in the hand luggage, they walked down the canvas-lined gangway; hands clutching the thick rope sides, swaying on sea-habituated legs. Their cabin luggage was to follow them to the hotel but the hold luggage would be stored in a warehouse on the dock.

Mrs Wallace seemed happy to be home. ‘Welcome to Australia, dear. The hotel is scarcely a few minutes’ drive from the quay so it is hardly worth seeking out a conveyance,’ she said, pushing her damp hair from her eyes. ‘I’m sure you agree it will be good to stretch our legs.’

Mrs Wallace was set on a path and Maisie felt a stab of dismay. She had learned, often, during the six weeks of their acquaintance, that contradicting Mrs Wallace was like trying to hold back the tide. There was absolutely no point because it simply couldn’t be done.

The sun blazed down on the corrugated-iron sheds as they began their journey and there was no shade to be had. They paused where a single railway line bisected the wharf and a funny-looking little train let out occasional gasps of steam. A ferryman was tying up his boat, and other dilapidated vessels were bobbing on their moorings. Nothing looked new. She felt she had washed ashore at the end of the world.

‘Pace all right, dear? You look a bit wrung out.’

‘I’m fine, thank you, Mrs Wallace,’ Maisie managed. ‘I’m not quite used to the heat just yet.’

Mrs Wallace looked relieved and pushed on. They walked up the main street where a woman in a pale green dress was brushing the footpath to her shop and when they rounded the corner – two or three turnings further on – they stopped again. A battered sign nailed to a gum tree, handpainted in yellowing pink letters, read, ‘The Garden of Eden Guesthouse’. The house itself was half-obscured by an overgrown garden behind rusty wrought-iron gates.

‘What a dirty place,’ Maisie exclaimed, as they climbed the narrow steps to the front porch. ‘I imagined it to be white. Bleached, perhaps.’

She had also imagined a more intimate, inviting welcome to Australia. There was nothing in her future husband’s manner of address in his telegram, nor the accommodation he had arranged for her, that dispelled a deepening sense of foreboding.

The two women waited several days in Port Fremantle for the Blue Funnel coastal steamer; there would be five ports of call, dropping passengers at intervals over seven days, and then, after almost two months at sea, Maisie would meet the man she had been exiled to marry. At the third stop, Gantry Creek, Mrs Wallace would leave her for the home where she lived with her husband and seven children. Her husband had built the sheep station – apparently the size of a small country – from scratch. He was Scottish and, at just twenty-two, had panicked his grandparents with a persistent, phlegmy cough. Fearful he could be developing tuberculosis, and scared for the life of their only grandchild, they dispatched him to Australia to ensure the longevity of the Wallace line.

Maisie was fascinated by the few glimpses she had been given into Mrs Wallace’s life.

The first night, they had just finished their supper and were still sitting at the table in the dining room. She dropped a sugar lump into her coffee and gave it a swirl with her spoon. The sun was beginning to sink and glinted on the gold wedding band squeezing the flesh on Mrs Wallace’s left ring finger. ‘How did you meet your husband, Mrs Wallace? Were you already in Australia?’

Mrs Wallace leaned back in her chair, ran both hands round the square neckline of her dress and yanked it up over her cleavage. ‘No, dear. We met on the ship when I was coming over to begin my nursing in Perth. We were seated next to each other at the same table.’

Maisie propped her chin on her hand. ‘What happened?’

‘It was a very turbulent night. The ship was ploughing through the Atlantic. Do you remember how rough it was?’

Maisie nodded. She would not easily forget the enamel basin, the weak, sugary tea and the days confined to the cabin feeling wretched.

‘We were listening to the orchestra and talking a great deal. I remember – as clearly as if it were yesterday – that I was wearing a new black dress that was rather tight over the bodice and it was all covered with big shiny sequins and I had feathers in my hair. I loved that dress! Arthur leaned over to me and said I looked like an exotic princess and asked if I would take a chance on a waltz with him. He was so handsome with his hair slicked down, he made me tremble inside.’

‘And did you dance and fall in love?’

‘We danced for a bit, yes. The boat was rocking considerably, and it threw us together. Quite literally! And that was that.’

Maisie imagined the handsome Scotsman dipping down on one knee and begging for her hand in marriage. ‘Did he propose straightaway?’

‘Not precisely, dear.’ Mrs Wallace adjusted her spectacles. ‘We had only just met, but our fates were intertwined from that moment on.’

Maisie wondered idly whether there would be such a moment for her and her captain. Beyond the grubby balcony and peeling shutters of the hotel dining room, she could see the tall masts of the ships at anchor in the bay. She imagined him at the helm, singing a romantic solo of his own as he charted his course to claim her.

The next afternoon, Mrs Wallace put down her coffee cup and blotted her top lip. ‘I’m off for my nap, dear. I think you should have one too.’

‘In England, people never sleep in the afternoon,’ Maisie said.

‘That is irrelevant here. When you are married, your husband will come home for his lunch at midday and will, I am sure, lie down for an hour or so before he returns to his office. It’s a common practice and one you should adopt too. After that, you will be free to socialise.’

Maisie wasn’t certain if Mrs Wallace was implying that she would be joining him or having a private nap of her own.

‘As a young English woman and a newcomer to the town, you will be screened by the ladies, ogled by their husbands and judged by your help. You must have an At Home Day once a month during which you will invite all the resident ladies of your social circle to tea, cards, pianoforte recitals – whatever you choose to host. You must serve afternoon tea off your best china. Tea is a formal occasion, so you must produce the lightest of cakes and instruct your help how to serve them.’

Mrs Wallace delved in her mending bag and from the depths produced a wooden darning egg as well as her scissors and an assortment of threads. A tan lisle stocking lay limp on the round table by her elbow. ‘You must repay their visit on their appropriate At Home Day, leave two cards of your own and one of your husband’s. You will be expected to attend all other At Home Days besides your own; it will be seen as the epitome of impoliteness if you fail to appear. The likelihood is that you will not care for the majority of these women. The old tabbies will want to get a look at you, and all the young unmarried girls will critique your appearance and scrutinise your wardrobe and probably gossip about you too. It is very important that you are sucked into the bosom of your new life from the start, or you will find yourself very lonely indeed.’ She pushed her spectacles up her nose and squinted at the eye of her needle.

Maisie thought this sounded utterly ghastly. ‘I must confess that I am surprised, Mrs Wallace. This sounds much more formal than England.’

‘Of course it is, dear. It is all people have to hold on to. They have created a tiny replica of Home, and you must slot in and run with it.’

‘But what if no-one likes me?’ Maisie said.

Mrs Wallace began to stab her needle through the stocking. ‘You must work hard to ensure that they do. Your husband will not give up his drinking, his clubs or his gambling for you, nor should you expect him to. It is your job to adapt to him and his lifestyle. If you don’t fit in, he will simply carry on as he did in his bachelor days and leave you at home. Even though you might find yourself in a comfortable position financially, if you are isolated socially, you will be overwhelmingly alienated and unhappy.’

‘But that’s …’

‘The way it is in frontier towns, my dear. You must ensure that you succeed. You are going to need to toughen up and develop a backbone. Think of your mother. That should starch your resolve.’

A few days after their arrival in Port Fremantle, Maisie slept in well beyond breakfast.

When she woke, she saw that Mrs Wallace had made good use of the opportunity to sort through her cabin trunk. She sat up in bed, a poor effort at a smile wobbling at the edges of her mouth. Slack facial muscles were not to her mother’s taste. I do hope you are not about to cry, Maisie.

She pinched the insides of her wrists; the pain was distracting. ‘Good morning, Mrs Wallace. Did you sleep well?’

Mrs Wallace looped the wide leather handles of her handbag over a fleshy forearm and patted the contents.

‘Passably, thank you. A breakfast tray – rather desiccated, given the hour – is beside your bed if you are hungry. I thought we might attack the shops today. An indelicate question, I know, but do you have funds?’

With a quick up and down of her chin, Maisie confirmed that her parents had not cast her adrift without money.

‘Good. We must spend some time at the shops while we are here. I have had a good look through your trunk this morning. I know you will think this a dreadful invasion of your privacy, but it had to be done. You need cotton dresses to keep you dry, loose underwear and silk stockings, a wide-brimmed hat and parasol to keep the sun off your face as well as gloves to protect your hands. And you will need to do something about those dreadful shoes of yours. They are not suitable for this climate. Whatever can your mother have been thinking?’

Maisie picked a corner off a dry bread roll. ‘But Mrs Wallace, if I wear any more garments, I shall die!’

‘You cannot let your lovely white skin become tanned by the sun, dear. You must not turn brown like a coloured. That would be certain social suicide. I suggest you acquire a cotton kimono-style wrap to keep yourself cool when you are at home. You can wear it without any underclothes, provided you are alone and you keep the doors locked.’

Maisie stared.

‘And don’t forget, dear. If you are accepted wholeheartedly into the social fabric of Buccaneer Bay, you will need a range of evening clothes and ball gowns. I expect you have them already in your hold luggage or you will order them from Paris or London if you find that what you have brought is not in tune with what you need. Everyone dresses properly for dinner here, regardless of the heat.’

The day before the coastal steamer was to set sail, Maisie woke to a pain in her abdomen like a sword, skewering her to the bed. A ripple of queasiness rose from her stomach and sour saliva filled her mouth. The shared bathroom was a long way down the landing at the bottom of a splintery wooden staircase, and as she stood her legs felt achy and weak. The bedroom door had warped in the heat and she had to lean hard against it to push it open. She mistimed the manoeuvre and the door swung away from her, crashing her sideways into the wall.

‘Is everything all right, dear?’ Mrs Wallace called across the room.

‘Oh!’ Maisie said, sinking to the floor. ‘I have The Visitor and I feel very unwell.’

Her mother had always discouraged discussion of the monthly event and refused to have any sign of it brought to her attention. If she had to mention it at all, it was to be referred to as The Visitor.

She heard rapid footsteps and in a moment Mrs Wallace appeared in the doorway with her own supply of Southall’s Sanitary Towels for Ladies and hauled Maisie to her feet.

‘Come along, dear. We’ll have you fixed up in two shakes of a dingo’s paw and then you can hop back under the covers while you ride out the worst of the cramps.’ She picked up a rusty handbell from the nightstand by her bed and gave it a spirited rattle. ‘I’ll organise some morning tea with that dozy girl at the front desk. I always find a hot cup of tea does wonders when we are not at our sparkling best.’

Maisie climbed into bed and a short while later, a lumpy, dark girl with hunched shoulders and downy cheeks clattered up the stairs with the tea. She wore a faded blue dress that was too small around her hips and revealed the bulge of her suspender clips.

Mrs Wallace relieved her of the tray and set it down on a scratched wooden table – tutting loudly through her teeth – and pulled up a chair by Maisie’s bed. She administered a spoonful of Mrs Barker’s Soothing Syrup for Children in a cup of tea and swirled it round with a teaspoon.

‘I’m no Florence Nightingale, dear, but I think we need to ensure you are stocked with medical essentials before we board the coastal steamer. If you are afflicted this badly every month, you must arm yourself accordingly. I have no idea what you might be able to purchase up in your backwater of a town, but we must assume that there will be very little in the way of ladies’ supplies or medicines. You need to be prepared. Consider it a battle plan for a lifelong siege!’

Maisie reddened and sank down between the sheets.

‘Have you not organised sanitary protection for yourself before?’ Mrs Wallace leaned forward to the morning-tea tray and poured herself a cup.

Maisie shook her head, ashamed. ‘I never visit shops by myself. I rarely go out alone. Sanitary napkins appear in a drawer in my bedroom, and I’m sure the maid must keep a note of how many I use each month because the supply remains constant. I can’t think my mother would ask for such a private thing in a shop. I’m certain everything comes in the post.’

‘How does your mother think you will cope by yourself?’

Maisie shook her head and pictured the brown paper packages on the hall table in London with their plain address labels. ‘We never had that conversation.’

She found herself thinking back to a Christmas Eve when she was little. There was a large fir tree in the hallway, the topmost branches reaching almost to the third floor. Its boughs glittered with glass balls, lighted candles and small gifts wrapped in coloured paper. Underneath the spreading lower limbs were larger brown parcels with handwritten labels, tied up with curly string. On one of the lower branches she discovered a tiny teddy bear, a woolly blue scarf wrapped round its furry neck. Delighted, she reached up and tried to grab it.

‘Don’t touch!’ Her mother had swatted her hand away, pulled the bear from the branch with a tenderness Maisie had rarely seen from her and cradled it in her arms, like a baby.

Mrs Wallace rattled her teaspoon against the inside of the cup. ‘Do you know anything about your husband-to-be?’

Maisie felt the heat in her face. The shock of the memory had caught her out. ‘I know nothing about him other than that he is a sea captain. I have no idea what he looks like or even how old he is. He wrote to my parents before Christmas saying he was in a position to offer me marriage and so here I am two months later in Australia.’

Mrs Wallace looked stunned. ‘Did you not have any say in the matter?’