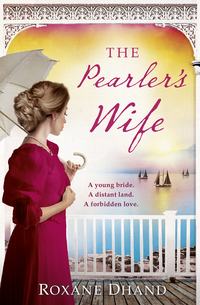

The Pearler’s Wife: A gripping historical novel of forbidden love, family secrets and a lost moment in history

Maisie shook her head. ‘I think it was all arranged before they told me. It seems as if Cousin Maitland sent over a shopping list and I was one of the items on it.’

Mrs Wallace laughed. ‘I’m sure that was not the case.’

‘No, really,’ Maisie continued. ‘In my hold luggage I have a twenty-four-place china dinner service, glassware, linens and silverware and all sorts of other things too. Mama and Father said nothing about the expense. I suspect they were glad that someone would remove me as far away from them as is geographically possible on this planet. I’m not exaggerating – I looked it up on the atlas.’

Mrs Wallace patted the back of her hand. ‘Don’t be so introspective, dear. You overthink everything. No parent would throw their child to the lions without being reasonably certain she would survive, and they would most certainly have sent you on your way with a substantial dowry. Every parent wants a good marriage for their daughter – a husband and place in society. But enough of that. On a practical level, for the monthly trial, you will find it impossible in the heat to wear the rubber protective apron you have brought with you under your dress. It will stick to you and give you prickly heat. You’ve probably had a bit of that already on the ship with all those garments you’ve been wearing.’

Maisie thought her own face must have stained as red as the counterpane on her bed, but Mrs Wallace said all this without a hint of embarrassment.

‘You are going to have to manage with those sanitary knickers you have in your trunk. They are a boon in a hot country, provided you don’t overexert yourself. We might try to find you a night tidy, though. We should be able to pick one up from the chemist here. It’s made of muslin and has a waterproof lining. It will prevent accidents on the sheets and unnecessary extra laundry for your help. I’m glad also that you have brought the metal stock box to keep the towels dry. Otherwise they will go mouldy in the wet season and I am sure you don’t want them infested with silverfish or moths. The best plan is to have a baby straightaway and have one every year for a while. That way, you won’t need supplies for years. It’s what I did.’ Mrs Wallace poured Maisie another cup of tea.

‘Does it hurt like this, having a baby?’ Maisie ventured, knowing that she would never have asked this of her mother.

‘Were you not given any indication of what to expect?’

Maisie cringed, pulled the sheet up under her chin and sank down further towards the foot of the bed. She knew the rudimentary facts of life, but her knowledge of the sexual act and its consequences was vague. As far as she knew, her parents did not undress in front of each other, and they slept in separate beds in different rooms. She hadn’t really thought about the mechanics of procreation. She supposed that her mother must have lifted her skirts at least twice and invited her father in, but specific details hadn’t seemed important. Ignorance had enabled her not to incorporate the physical reality into her romantic dream.

Mrs Wallace pushed her generously padded posterior towards the back of the chair and set about a lengthy narrative on the subject of the needs and desires of the gentleman and his insatiable ‘boneless finger’.

‘But I am sure your husband will be sensitive to your needs and will treat you with the greatest of respect. And you can always say you have a headache – it’s an acceptable excuse that no decent man would contest. I have a copy somewhere at home of the Physiology of Marriage. I’ll search it out and send it to you.’

Maisie slid down another inch beneath the sheets. ‘What is that?’

‘The last word in marital relations. Perfect for you, I would have thought, with a mother who …’ Mrs Wallace bit her lip.

‘Who what?’

Mrs Wallace refilled her teacup and took a noisy gulp.

‘Who …’ She balanced the saucer on the chair arm. ‘I believe she was rather keen on someone else for a while.’

‘Before she married my father, you mean?’

Mrs Wallace lifted the teacup and Maisie watched the blush wash over her face. ‘Exactly, dear. Now you’ll have to remind me what I was saying just now as I have lost my train of thought.’

‘Physiology of Marriage and why it will be perfect for me, given my mother.’

‘Oh yes! The newspapers here have been running advertisements for it, but you wouldn’t have found it in England, as it is an Australian publication. It is only available here via mail order. As I said, I’ll send it on to you straightaway so you will have it before your wedding night. It might make you less anxious.’ She dispensed another spoonful of syrup into Maisie’s tea. ‘Now, drink this down and have a little nap. I’m going to sit on the balcony and make a list of what you will need. When you wake, we’ll have luncheon and then we will see about stocking you up with supplies.’

Maisie reached for the syrup bottle and squinted at the label, feeling faint as she studied the lengthy list of opiates, moving the black bottle backwards and forwards in front of her face trying to bring the tiny print into focus.

She gave up and sank back against the soft pillows, eyelids heavy, and in that brief moment she could not have cared less about Maitland Sinclair and his insatiable urges.

Chapter 4

ALMOST A WEEK LATER, just before sunrise, Maisie put on a new cream dress, revelling in its floaty freshness. She lifted her arms, testing the weight of the unfamiliar, soft, feminine fabric. She’d passed over a pick of her mother’s from Peter Jones and shoved it to the bottom of her trunk. Thanks to Mrs Wallace, she now owned a wardrobe of loose-fitting clothes appropriate for the Australian climate. She went out on deck, her new shoes noisy on the planking, and settled herself into a deckchair, the familiarity of the hard wood beneath her skirts reassuring. The purpose of her dawn expedition was to see a glorious sunrise – her last at sea for a while. But the sun remained persistently hidden somewhere within an angry purple sky.

She had been aboard the coastal hopper for six days, the pace of which would have made a snail weep, and was set to arrive in Buccaneer Bay that evening. The ship inched along the flat, grey coast, which provided little of interest beyond rocks and endless scrubland. She shivered as she picked out a light winking beacon-like on the shoreline, hoping it was not a warning of danger ahead.

Mrs Wallace was no longer on board. Two days earlier, she had disembarked at Gantry Creek, in a hurry to get back to her husband, her boys and their sheep in the Pilbara.

Maisie had become uncharacteristically weepy in her arms as they said their goodbyes. ‘What will I do without you, Mrs Wallace?’

The older woman pulled Maisie to her squashy bosom and said, with benevolent tartness, ‘What on earth’s got into you today? I am two days away. There are steamers every two weeks, and we will write. Don’t whine, Maisie. It makes you look feeble.’

Maisie had clamped her jaw shut. She knew better than to make a scene.

The steamer ploughed on, making deep furrows in the turquoise sea. Lulled by the regular rolling of the boat, Maisie was rocked into dreams. Her father was wearing his judge’s wig. She was in the dock pleading for mercy. Her mother was prosecuting and demanding that she be hanged from the neck until dead. Her father placed a black cloth on his head, shook his head and removed it. The punishment was too severe, he said, and commuted the sentence to life imprisonment in a penal colony. Australia, he declared, would be the perfect place for her to live out her days. She begged them to explain what she had done, but the judge banged his gavel on the bench. It is the wish of this court.

She woke in the grip of panic and for a moment couldn’t think where she was. Voices floated up from the third-class deck. She recognised one: William Cooper, the English diver who had made the speech at Port Fremantle. The brass band had been loud but it hadn’t completely drowned him out. She was glad she hadn’t seen him since; he made her feel flustered. A huge fish leaped out of the water next to the steamer and fell back with a splash. It jumped again, dived deep and disappeared. She envied its freedom.

The arrival of a coastal steamer was apparently a big event at Buccaneer Bay. As the light began to fade and the steamer dropped anchor amid a dense woodland of naked masts, the handful of remaining passengers crowded the decks and peered out into the gloom. As the steamer lurched against its moorings, Maisie watched the commotion and scanned the waiting throng. On the wooden jetty below, a crowd had gathered – waving handkerchiefs and hats – all jostling to come on board. The men were spotlessly white, splendid in their immaculate tropical suits and solar topis. A European woman wearing an ankle-length dress was negotiating her way round a stack of boxes. Maisie couldn’t tell her age, but Mrs Wallace had been right: a hat, veil, gloves and high-ankle shoes assured that the sun would never glimpse her skin.

The boarding party surged up the gangplank like a tidal wave. Men with waxed moustaches, some with burned complexions, elbowed their way on deck. The noise jangled Maisie’s nerves and she looked around, unsure what to do. Was Maitland Sinclair in their midst pushing his way up the ramp, eager to claim his future bride? She started to panic. How would he know her? She followed the crowds into the first-class lounge, where the captain was dispensing complimentary drinks. She accepted a glass of lemonade from a steward and settled on a velvet banquette, her eyes trained on the doorway. Her heart was battering her ribcage like a parade-ground drum, her palms damp and clammy. Surely he would come soon? Or maybe he’d changed his mind and she’d travelled thousands of miles for nothing? She felt faint with misgiving.

Time passed and still he didn’t come.

In the lounge, Mr Farmount started to make a speech. She looked up and tuned in to what he was saying. She couldn’t avoid it; his voice was so loud it reverberated around the room. He was introducing the English divers to the four master pearlers who had agreed to employ them, his speech a poorly disguised sales pitch for the diving company he represented. He talked at length about a new, engine-driven air compressor, which had not previously been used on the pearling grounds of the north-west. It would transform safety on board, he said. Hands were shaken, contracts exchanged and start dates discussed. The master pearlers quizzed the Englishmen about their training, and their experience of diving at great depths. Toasts were made, backs were slapped and the drinks kept on coming. Maisie wondered how they could concentrate with so much alcohol coursing through their veins.

William Cooper was sitting by the bar, wiping his forehead with the back of his arm. She saw that there were dark damp patches under his arms and around his collar. His eyes lit up for a moment at something the barman said and she heard him laugh. It sounded joyous, and her heart dropped then. When was the last time you were really happy? She searched for the answer but it was nowhere to be found.

From feet away a voice said, ‘Cousin Maisie?’

She started and turned her face towards the voice.

He was dressed in a cream linen suit, with a spiky-leafed flower she didn’t recognise in his lapel. It was a stark contrast to the flabby outline of his jaw and the puffy pouches under his eyes. Short, bald and fair-skinned, he had a misshapen nose, ruddy flesh pitted with blackened pores, and clamped between his nicotine-stained teeth was a short-stemmed pipe.

She shot up, clutching her glass like a lifebelt, and spilt yellowish liquid down the front of her dress. ‘Cousin Maitland?’

Pipe still in his mouth, he took her hand between both of his and pumped it up and down, then dropped it just as rapidly. He rubbed his palms together and peered at her with assessing eyes. She looked for a sign of approval but there was none. Disappointment settled heavily on them both.

He didn’t introduce himself. He didn’t ask, with the touching solicitude she’d imagined, if her journey had been bearable. If she was managing in the heat or was missing her parents. She turned her thoughts to her appearance, to lighter complications and concerns.

‘I must look a mess.’ She ran a shaky hand over her hair.

He was standing so close to her she could smell his sour breath. He took hold of her arm, pinching her flesh hard through the sheer fabric.

‘Won’t matter what you look like. No-one’s going to care. Come. Everyone’s waiting.’

She would have envied his lack of concern had she not been its collateral. She could see that there was nothing about her that raised his interest; that her presence seemed to annoy him. She tried to think where she had gone wrong.

‘Waiting?’ She pulled out her handkerchief and dabbed self-consciously at the stain on her dress.

‘Yes. Waiting for you. Come on. No time like the present.’ He bedded his free hand in the middle of her back and propelled her along the passageway into the stateroom. ‘We need to get it over with. There’s nowhere for you to stay if we don’t. It’s the lay-up.’

She had not the first idea what he was talking about.

The ship’s stateroom was a bear pit, crammed with people she didn’t know and smelling foreign: of alcohol, tobacco and stale sweat. She pressed a finger across the underside of her nose and tried to force down the fear. She could sense that all eyes were upon her, triggering a hot blush on her face. She couldn’t be the centre of attention. Her mother would have whipped her for such presumption. She had been conditioned throughout her life to shun the limelight yet now all eyes were on her. Her knees began to wobble. She wanted to run, to leave as quickly as she was able. It had been the safest course at home. Frightened she would be scolded, she tucked her chin to her chest and began to apologise for her lack of manners.

The ship’s captain held up a finger, snapping off her words, and twisted the strap of his watch. He stretched his mouth in a smile and pointed at a chair.

‘If you would care to take a seat, we can make a start.’

Maisie turned to Maitland. ‘I don’t understand.’

‘Dear little Maisie. You’ve travelled miles to be my wife. All my friends are here on this ship right now. It makes perfect sense to marry with everybody present, and make a party of it.’

‘Are we not to marry in church?’

‘No need. The captain can marry us. It’s often done at sea.’ He nodded at the captain, who squeezed out another smile.

‘But we aren’t at sea.’

‘As good as.’

‘Is it legal in the eyes of God?’

Maisie started as Maitland punched the back of the chair. ‘Lord above, Maisie. Of course it’s legal. Do you think I would do anything illegal?’ He jabbed her in the ribs with his elbow. ‘Now shut up. You’re embarrassing me.’

Maisie watched him, trying to gauge what had triggered his reaction.

The captain shuffled his feet and said nothing.

Although her legs were trembling, Maisie felt she had to say, ‘I should like to put on my wedding dress.’

‘What for?’

‘I’ve brought it thousands of miles for this occasion. I’d like to wear it on my wedding day. The dress I’m wearing is crumpled and stained and I should like to change out if it.’

A shadow of irritation crossed his face and Maisie saw him clench his fist. Instinctively she stepped back, and ducked her face once more into her chest.

The captain tapped the glass face of his watch. ‘Are we able to proceed, or does the lady need a moment?’

‘She’s fine. She doesn’t need to dress up.’

The captain checked his paperwork. ‘Who are the bridesmaids?’

‘Miss Locke said she’d stand in.’ He indicated the woman Maisie had seen on the gangplank.

Maisie smiled across at the elegantly clad stranger. ‘Are there no other ladies here?’

Maitland’s lips tightened. ‘Mostly in Perth. They go south for the Wet. It’s too bloody uncomfortable for most females at this time of year. They’ll flitter back in March, give or take.’

She tried to unravel her disquiet as, wearing a stained dress and with tears not far from surfacing, Maisie promised to love and obey Maitland for the rest of her life, her spirits as low as the hemline of her dress.

The party was in full swing by the time it was dark.

Maisie slipped away to her cabin. Lit only by the overhead lamp, the shadows dimmed the horror of her situation. No-one noticed she had left the wedding party. The event had not been about celebrating a marriage. Maitland had barked his responses during the ceremony, as if he were commanding a fleet of warships; she had responded in a wavering treble that Mrs Wallace would have despised.

Her husband – she shivered at the title – was now enveloped in a wave of backslapping and ribald well-wishing. She sank down onto the bunk, wondering where her great hope for happiness had gone. She lifted the lid on her trunk and fingered the princess gown of white duchesse satin that she would never wear. Her trousseau had been handmade in London and had cost a great deal of money. She ran her hand over the dress’s silky fabric, which had been embroidered with pearls – a most appropriate and clever touch, the dressmaker said, being associated with brides and weddings and the profession of her future husband and all. For Maisie, though, they represented far more than that; they were her freedom.

Everything screamed at her that this marriage was wrong.

The fabric slipped through her fingers like sand. The outfit she was to wear for her reception was of chiffon satin in the fashionable ‘ashes of roses’ shade with an overdress of silk and gold net. It was the most beautiful thing she had ever owned and he had cheated her out of wearing it. The only time expense had ever been lavished upon her, and it had gone to waste. She replaced the dress in her trunk and packed away the last of her things, wishing she could load it onto another ship and sail back the way she had come.

There was a tap on the cabin door. Maisie jumped up and clutched the neck of her dress, her heart stuttering. Was this Maitland, come to claim his prize?

‘It’s the porter, Miss. May I collect your cabin luggage?’

‘Yes, of course,’ she rasped, and coughed in an attempt to ease the pressure clogging her throat. ‘Give me a moment.’

She took a final look around the hot, brown box that had been her home for eight days, and opened the door. She followed the porter out onto the deck, which was piled high with baggage and crates of drink. From the bar, she could hear the plonk plonk of an untuned piano and, in the distance, a train whistle. She found that surprising. She hadn’t expected a locomotive in Buccaneer Bay.

Maitland hadn’t bothered with private transport for his bride. Normally, he told her, he would have walked home, as it was only half a mile over the jetty. She’d had a long day though and might be glad to take the steam-tram. He helped her onto the open carriage and squeezed her onto the last vacant bench, wedged between the window and an elderly man of significant girth. Maitland slumped down in the corner opposite and closed his eyes. The tram shuddered to life and soon they were rattling over its rails across the wooden jetty towards the lighthouse.

Maisie leaned forward and tapped his arm. ‘Tell me about your life here,’ she said.

He opened his eyes and cracked his knuckles, one by one. ‘Nothing to tell.’

‘But I’d really like to know what to expect.’

He looked at her once and turned away, his foot banging up and down on the steam-tram’s floor.

Theirs was the first stop. He stood up and prodded her shoulder with the stem of his pipe. ‘Here we are. This is where we get off.’

The single-storey house was on the edge of town. In contrast to the tall grey townhouse where she had grown up in London, this was low – a squat white rectangle, one of the long sides facing the sea. Beyond that, it was too dark to see.

There were three steps up to the verandah. She put one foot on the bottom step and clutched the handrail. Maitland nudged her up towards the front door. ‘Home, sweet home,’ he said.

Maisie worked the gloves in her hands, hoping the torque of the twisted fabric would give her strength. ‘It’s a bit too dark to really appreciate the house, Maitland, and it has been a very long day.’ She thought of Mrs Wallace. ‘I have a dreadful headache and I’d really just like to go to bed.’

He didn’t seem to register her remark. He struck a match and flared a carbide light.

The smell was too strong: an overwhelming reek of garlic mixed with damp. Maisie’s nostrils flared at the sting of the smoke.

‘Maitland?’ She shuffled her feet. It had been hours since she last used the ship’s facilities and her bladder was stretched tight, like her nerves.

‘What?’

‘Might you show me where I can tidy myself?’

A jagged streak of lightning illuminated a wide verandah, which ran the length of the house. He took a half-step towards her, his huge hand extended. She shrank back against the doorjamb, fearful that he might touch her.

‘Maitland?’ Her voice was small.

Something in her tone reeled him in. ‘The bathroom is at the back,’ he said. ‘I’ll show you.’

He didn’t understand the euphemism. Hardly more than a rudimentary shack tacked onto the back of the bungalow, the bathroom housed a stained tin bath and shallow basin sunk into the top of a wooden table. A small woodchip water heater sat on the floor beside a large enamel jug. Two taps were connected to the heater – one stretched over the bath and the other was attached to the end of a long metal pipe, running the length of the wall and coming to a halt over the basin. A single shelf over the sink provided the only storage space. It was cluttered with his own things. He had pushed nothing aside to make room for her in his life.

‘This is the bathroom, Maitland, but what I need is the lavatory. Might you show me where that is, please?’

The toilet was outside, housed in its own separate cubicle abutting the back fence, fifty yards from the house. A crushed-shell path, lined with upturned glass bottles sunk deep in the soil, led to it from the back door.

Maitland waved a fleshy hand. ‘There’s your lavatory, Maisie. It’s out the back so you won’t be disturbed when the shitcan collector comes to empty the dunny in the early hours.’

The obscenity slapped her in the face, like a blow. ‘Do you have a lantern I might borrow?’

‘No, I don’t. I piss off the verandah at night.’

He watched her pick her way down the path.

‘Watch out for snakes and spiders,’ he called after her. ‘Lots of them bite.’

The toilet was housed in a galvanised-iron hut. Squares of paper, threaded on a string, were nailed to the wall. She had no words to describe the smell. She covered her mouth with her handkerchief and hurried back to the house, the hem of her dress trailing through the thick, dark earth.

Maitland hadn’t moved from the back door. ‘Drink before bed?’ He waggled a bottle at her.

Maisie was dry-mouthed, her heart thumping so hard she wondered if he could see it through her dress. This is it. Coarse and without appeal, the man repulsed her. She had spent all her life dreaming of Snow White’s handsome prince who would kiss her gently awake from her sleepy existence. He would kneel at her feet, hand pressed to his heart, and beg her to be his bride. The reality was that she had married a fat, ugly toad.

Mrs Wallace had not painted a romantic, loving picture of the marriage act. If he was a good man, she said, he would coax her, his frightened bride, with kind words and understanding. Otherwise, among a lot of talk about sheep and animals, things would have to be borne. She sank onto a kitchen chair with shaking knees and picked at the neck of her dress. ‘Perhaps I might,’ she said.

‘You’ll have to get up. The drinks are next door.’