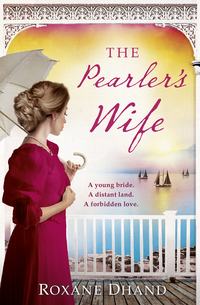

The Pearler’s Wife: A gripping historical novel of forbidden love, family secrets and a lost moment in history

She followed him down the passage, their footsteps echoing on the floorboards. A pile of unopened letters lay on a polished wooden table and, somewhere in the house, a clock chimed the hour. He stood in front of a side table, and over his shoulder said, ‘What’s your poison?’

‘Sherry?’ she replied, both hands locked on her handbag.

‘No can do. Gin, brandy, whisky, champagne or wine.’

‘Gin, then.’ Her voice was high and thin.

He turned towards her and held out a glass. ‘Quick nightcap and then let’s get off to bed.’

For the second time that day, Maisie was taken to a room she had no desire to enter. It was a small box room whose walls and ceiling were covered with beige hessian. It was intolerably hot and smelled of damp.

‘This is your room. It’s adjacent to my own,’ Maitland explained, lighting another carbide lamp. ‘You’ll be all right in here. There’s an empty drawer for your things in the dressing table but not much space in the wardrobe. You’ll have to manage. The bathroom is down the verandah on the right, if you’ve lost your sense of direction. I’ll be able to hear when you’ve finished in there.’ He stood in the doorway and seemed to hesitate. ‘I’ll probably be gone in the morning before you’re up, so just have a look round and sort yourself out. Good night.’ He shut the door behind him.

Alone among his clothes, she sat on the bed, quailing in the near dark. Though her parents had separate rooms, she had imagined a shared bed for her wedding night. Maybe Maitland was preparing to receive her on the other side of the door and his bachelor room would eventually become theirs? An image of him undressing came into her head, but she squeezed her eyes shut to block it out and tried not to panic. After a while she opened her eyes and looked around. Her trunk was not there. She was without friends, possessions or courage. She undressed and folded her clothes neatly into piles on a chair, shoes side by side underneath, through years of habit. The bed was low, covered with a single sheet, tucked in tightly at the corners like a parcel. She peeled back an edge and got in, dressed only in her shift. A few moments later she thought she heard Maitland close a door along the passage. The sound of whispering and then a deep cry. Her heart quickened and sweat trickled down her neck. She strained her ears listening for footsteps and stared at the wooden handle on her door, waiting for it to turn. This is it, she thought, the absolute edge of the cliff.

She lay on her back, eyes open in the darkness, and stared at the knob for most of the night, scarcely blinking, but it never moved.

Chapter 5

THE NEXT MORNING, SHE was startled awake by the smash and splintering of crockery. She lay absolutely still, rigid, her eyes wide, waiting with panic for the door to burst open and Maitland to appear, demanding his husband’s dues.

‘Knock, knock.’ The voice was unfamiliar, certainly not Maitland’s.

She was too scared to sit up, and so sank down dragging the sheets to her chin, her pulse jumping in her throat.

A Chinese man with a coffee-coloured face, his teeth shining even whiter than the dazzling singlet he wore below it, peered round her door. His gums looked blue against the shiny white enamel. Maisie twisted the gaping neckline of her nightgown closed between her thumb and forefinger.

Pinned to the bed by his enquiring gaze, she pulled the sheets more tightly around her. ‘Who are you?’

A half-smile hovered at his mouth. ‘Cook-houseboy, Mem. I everything here.’

‘Do you live in this house?’ She shrank back against the pillow, her stomach contracting. Maitland hadn’t mentioned servants, though she had realised there must be some. ‘What’s your name?’

‘Duc, Mem.’

‘What do you want?’ She tightened the sheet round her neck.

‘Bossman say me bring you cuppa tea.’

She willed herself calm. ‘That would be welcome.’

‘You okey-dokey, Mem?’

She dipped her chin. ‘Is Captain Sinclair here, Duc?’

‘Boss? No, he gone working. He come back afternoon or night time. Maybe if.’

She sat up from the pillows and elbowed her way up the headboard. ‘Maybe if?’

‘Seven o’clock. Maybe if eight.’ He seemed to nod and shake his head at the same time, leaving Maisie with no idea what he meant.

‘What time is it?’

He gave her a look, which made her feel stupid. ‘’Bout morning-tea time.’

‘Has my trunk arrived from the steamer?’

He put his head on one side and wobbled it again, grinning like a madman. She could see he hadn’t understood her question.

‘Big black box.’ She drew a rectangle in the air with both hands.

Duc pulled his mouth wide. ‘Yes. Him arrived. I bring for you?’

‘Tea first. Then you can move the black box.’

The mouth widened. ‘You get up and go verandah. I bring tea. You want eat?’

She couldn’t remember when she’d last eaten. ‘Maybe something small?’

‘I go see what’s what.’ He put his hands together and bowed.

She half-expected him to reverse out of the room. For the first time in days, she almost smiled.

Duc carried the tea tray as if he were carrying the crown jewels on a velvet cushion, his arms stretched out and reverent. When he saw her, his face lit up. He dropped the tray on a side table and bent at the waist, paying homage as if she were a minor royal. Clay tea things and a plate of scones rattled together, sloshing sugar and milk onto the tray cloth. Maisie wondered about him, supposing the smashed crockery that had woken her had been his handiwork. She picked up a sugar-crusted cake and took a bite. It was as dry as the Sahara.

‘Is there any butter?’

‘No. Him butter come in tin. Very oily.’ He shook his head to one side.

‘Milk?’

‘Milk him cow gone.’

Maisie had trouble with this one. Did they have a cow that had gone away? Or died? Or did they have a milk source that had run out? She would have to try harder. ‘Jam, then?’

‘No, him all used up. Poof.’ Duc threw his hands in the air.

Maisie shifted in her seat.

Duc missed nothing. ‘You not comfy in boss fella’s house? You want I bring more something?’

‘I’m fine, thank you. Does the captain have a maid? A girl who comes in to help you?’

‘Oh no, Mem. No girls.’

Maisie looked at him. ‘No girls?’

‘No. Just him and me here, Mem.’

Maisie drank her pot of tea and washed down the rock-hard scones, which were stale enough to endanger teeth. She had only intended to eat one but had allowed herself to become distracted by her new surroundings. In the daylight she could see that the house was built on concrete legs, and from the shady west-facing verandah she looked down onto a stretch of sand alive with activity. The tide was out and it seemed as if an army of tea-coloured locusts was stripping the beached sailing boats of their contents. Coils of rope, baskets and lengths of anchor chain were being lugged up the sand. Sails were taken down from the riggings and dragged up the dunes where they were spread out for inspection across the high ground.

She shifted her gaze towards the lighthouse, which was as clean and bright as tooth powder. Next to it was a collection of iron sheds and warehouses. Two men were separate from the rest, deep in conversation. The shorter of the two was waving his arm at the task force on the beach. The other, she saw, was William Cooper – the tall English diver from the steamer – his dark head framed by the brilliant blue sky. Something tugged within her and she stared, her chest tightening as she took in the tilt of his head, the set of his shoulders. Even from this distance she could see that his skin was glossy with sweat. It glistened on his face like sunlight on water, and she could almost feel his body heat. She watched him twist off his boots and socks, and fold his trousers in neat pleats to the knee. He looked as if he was going to walk down to the water’s edge and paddle in the sea.

He patted his trouser pocket and pulled out the makings of a cigarette. The process made her frown. She knew she had seen him do it before but she couldn’t remember when.

Duc shuffled into view, his big toes straddling a Y-shaped strap on flat, slappy shoes. ‘You all done tea, Mem?’

Maisie tore her gaze from the figure on the foreshore and tried not to stare at Duc’s feet. She had never seen footwear like it. ‘Yes, thank you, Duc.’

She drained the last drop of lukewarm tea from her cup and rose from the chair. Her dress, the same dress she had worn for her marriage ceremony the day before, clung determinedly to her skin. She pulled at the neckline and flapped it up and down, trying to find some respite from the stifling heat.

‘Perhaps you could show me round the house?’

Duc beamed, his eyes sparking with what she thought was happiness.

Maitland’s bungalow – he had named it Turbine after a winning racehorse he had once backed – was a large oblong. Elaborate white fretwork surrounded wide latticed verandahs framing the house. The bungalow was set away from the acre-block housing she would learn was the ‘English’ part of town, and Maisie couldn’t help but wonder why he had built his house so far from the centre of things. At the front of the house, Turbine’s lush green lawns rolled out to the edge of a blood-red cliff that overlooked the ocean. They had no neighbours.

The bungalow was designed to be airy. Duc explained that the boss fella’s house had been built to follow the construction lines of a ship.

‘This housie builded by them Jap fellas.’

‘I’m sorry?’

‘Them Jappy fellas in Asia Place. Before him government say bye-bye to best workers.’ Maisie let his remark pass. She had been force-fed a diet of racist extremism since she boarded the steamship to Port Fremantle almost two months ago and was still struggling to digest the bigotry.

‘Mem Tuan. You listen?’

‘Yes. I’m listening. Tuan?’

‘Means boss. Them Jappy fellas build things good and use same wood for lugger boat. So him deck become verandah, inside boat is inside bit of house and sails on boat is big blow shutters.’

Duc was speaking a language she couldn’t comprehend, and she found herself mirroring his expression, stretching her mouth wide in a mirthless grin till her jaw ached with effort. She waved at steel cables that crossed over the roof like rigid string, anchored to the ground by fastenings sunk deep into cement.

‘Is for big-blow windies, Mem. Keep house on spot.’

She pointed at the metal-capped cement pillars beyond the verandah.

‘Hims is for creepy-crawlies and snakes and eaty ants.’

‘You eat ants?’

Duc rolled his eyes. ‘No eaty ants, theys eaty house. We no eat-im.’ As they continued the tour of the house she pointed, he explained, and neither comprehended the other. She thought that the house perfectly reflected her husband: flat and stretched sideways rather than up.

The dining room was next to the kitchen at one end of the west verandah. The walls were covered with framed pictures of hunting scenes – slaughtered deer, tigers and elephants immortalised in their final moments. Huntsmen and hounds posing by their bleeding quarry. She imagined she could hear the call of hunting horns, and tried not to look.

At right angles, the verandah widened to accommodate the lounge furniture, which, Duc explained, was made of cane imported from Singapore. At the far end of the same verandah was a long, partitioned space.

‘This, Mem,’ Duc paused, waving his arms like a policeman, ‘is mosquito room. Where you and boss have sleep. Afternoon time.’

Maisie steadied herself on the back of a chair. So, this is when it would happen. The consummation of her marriage would be this afternoon – in the mosquito room – with Duc listening in.

Duc explained that the quasi-dormitory area was enclosed by fine steel mesh to keep out the biting insects. Full-length iron shutters protected the space from the elements.

‘And do you have a room in the house, Duc?’

‘I’s live at back near to boss fella’s room.’

Maisie was shown a further small verandah at the back of the bungalow that faced the garden, which Duc told her was his space, or words to that effect. At the back was also a small shuttered area the boss used as a second home-based office, and a large storeroom, which housed an impressive larder of canned food.

‘The three of us will be totally self-sufficient if the sky falls in!’ She laughed.

Duc looked at her with a broad grin, his eyes wide with hope.

‘What you say you teach me cook, Mem, so we okey-dokey when sky falls in?’

Chapter 6

THE SEAFARER’S REST HOTEL, built of iron and wood and overlaid with latticework, sat on a rise at the Japanese end of Royal Avenue, its elevated position giving it a good vantage point over the rest of the town. Buccaneer Bay had no high street in the traditional town-planning sense. There was no nucleus to the collection of buildings that had grown up behind the coastal sand dunes. As far as Cooper could tell, its only excuse for existence was that its inhabitants all shared the same unshakeable belief that there was a fortune to be made from pearl shell and another from the occasional treasure within. It was why he, too, was there.

It was ‘lay-up’ in Buccaneer Bay, a season of unrestrained madness. The lugger crews had lived and worked for nine months of the year in conditions in which even the most placid dog would have savaged its handler – and school was now out. Captain Sinclair had billeted both of his new employees, William Cooper and John Butcher, in the Seafarer’s, and the rent would cripple them until they could get out to sea and start hauling the pearl shell. The Englishmen found themselves hunkering down among men of every nationality who were steadfastly working their way through their pay. Drinking or gambling were the preferred nightly pastimes. There was little else to do.

Cooper paused now on the doorstep of the hotel and lowered himself gingerly onto the pale cane seat. His head ached in pulsating waves. The previous evening was a queasy blur. Between sunset and sun-up, he had held centre stage in the bar among Filipino, Koepanger and Malay residents, playing poker and matching their drinking, glass for intoxicating glass. Early in the evening, he had accepted a glass of potato-gin from a middle-aged Filipino man everybody called Slippery Sid.

Taking an eye-watering sip of the noxious liquor, Cooper leaned forward. ‘How many luggers are in this place, Sid?’

‘Mebbe more than three hundred.’

‘Does each one have a different owner?’

‘Nope. Some mebbe two, mebbe three. Big Tuan boss Mayor, he has lots, mebbe twenty.’

‘Captain Sinclair has how many?’

Sid took a swig of gin and held up three fingers.

‘How many men on each lugger?’

Sid explained that each lugger held two divers: a number-one diver – usually Japanese – and a trial diver, who was less experienced than the principal. They dived in turns. The diver had a man on board who tended his equipment, which made a total of three diving-related people. A common crew comprised the cook, four men to man the air pumps in shifts throughout the day, and the shell-opener, swelling the number to nine. Sometimes the owner-captain worked on board too. So, as far as Cooper could make out, there were generally nine or ten people on a lugger.

‘Does Captain Sinclair go out to sea?’

‘Him’s no sea legs.’

Cooper chopped at his windpipe and contorted his face. ‘Is the diving dangerous?’

Sid laughed. ‘You’s a scaredy-cat?’

Cooper shook his head. ‘No. The diving I’m used to is much more dangerous than here.’

‘Japanese dive best.’

‘Why?’

‘Have lotsa guts.’

‘And the best crews?’

‘All mix-up. Then no fighting.’

‘And do the Aborigines work on the boats?’

‘He no work on boats. White man don’t like blackfella.’

‘Why not?’ Cooper knew that imported labour was an issue in Buccaneer Bay, but not to use the abundant local workforce seemed like lunacy.

‘Blackfella scared of diving gear.’

‘So, the crews do not originate from here.’

‘All crew come work for three years then go home again. All very snug.’

Somewhere close to midnight, Cooper fell asleep over a glass of rum. Someone shook his shoulder and hefted him up the stairs to his balconied second-floor room, and he had woken the next morning at nine o’clock, slumped across the edge of the mattress, one leg tucked underneath him, still drunk.

He squinted at his watch. Captain Sinclair wanted him at his office before ten. The initial meeting with the captain on the steamship had made him jumpy. He’d been expecting a big welcome party, along the lines of the fanfare at Port Fremantle, but the captain had barely acknowledged him and had completely blanked John Butcher. Cooper had accepted the four-page contract from his poker-faced employer but had refused to sign it unread. The captain’s pale grey eyes had not been friendly. Perhaps Cooper was misreading it. After all, the man could not have known of Cooper’s attraction to the woman he’d watched the captain wed or that his bride looked like she’d made a dreadful mistake.

Cooper leaned back in the wicker chair and began to roll a cigarette, booze-shaky fingers making heavy work of the task. He licked the sticky edge of the cigarette paper and placed one end of the slim tube, pointed like the sharpened lead of a pencil, between his lips and lit up. He shook out the match, inhaled deeply and crossed his legs, shutting his eyes against the glare of the morning sun.

‘The view isn’t up to much, is it?’ a young-sounding female voice said.

Cooper cranked open his eyes, his roll-your-own smoke dangling from his lip.

‘Black mud and luggers. That’s all you can see during the lay-up.’

‘I wasn’t really looking at the view.’ He struggled to his feet.

‘I’m Dorothea Montague.’ She held out a gloved hand.

Cooper looked into the girl’s face. Dark hair piled up under a hat, round blue eyes, her mouth wide and soft. ‘William Cooper.’

‘I know who you are. My father is the mayor. We’ve been anticipating your arrival with great enthusiasm.’

‘We are all excited to be here,’ he batted back. ‘And keen to get started lifting shell off the ocean floor.’

‘A bit of a wait then for you, I’m afraid. Until the Wet’s over.’

‘Wet?’

‘Gosh, I always forget that Britishers from England don’t know what that means.’ She giggled. ‘It’s the time from November to March when the threat of cyclones keeps the fleets and crews onshore. Everyone gets drunk all the time and we have lots of parties. It’s great fun. And the repairs are done to the luggers. I expect you will be given some jobs to do. The paid workers are expected to muck in.’

‘Are not all Britishers from Britain?’ he queried.

‘No, silly boy. We are all Britishers in Buccaneer Bay. White people. Don’t you see?’

‘Yes, I do see. Thank you.’ Although he didn’t. He stole a glance at his watch. ‘Please don’t think me rude but I have to be at Captain Sinclair’s office before ten o’clock.’

‘Oh goodness. That’s right at the other end of town. Would you like me to give you a ride in my buggy?’

‘Would your father be happy for you to ride with a stranger?’

‘Of course. White people have to stick together, and we don’t go in for that chaperone Victorian nonsense that goes on in England. There aren’t enough women, silly boy. It’s no trouble, and I could call on the new Mrs Sinclair. She arrived last night and I heard her to be about my age.’

‘Yes, she is.’

The blue eyes expanded. ‘You know her?’

‘I’ve seen her. We travelled on the same ship from England.’ Cooper thought of the slight, blonde-haired girl with her pearl-white skin, and wiped a handkerchief over his forehead. Oh yes! He’d seen her walking on deck with an older woman he’d assumed was her mother. Last night she had married Captain Sinclair in the most bizarre wedding ceremony he’d ever witnessed. She is now his, he told himself, but the realisation gave him no joy.

Miss Montague twirled her parasol, shading pale skin. ‘You should buy a hat. Your skin will really darken with the sun, and you don’t want people mistaking you for a coloured. That would be suicide, socially. Our people won’t invite you to anything if you’re all brown.’ She pointed at a horse trap tethered to a rail under the hotel’s awning. ‘Shall we go? The sulky is just there.’

He was sweltering and nauseous with a hangover beating a call to temperance in his skull. Without altogether thinking it through, Cooper accepted the offer and followed her out. He regretted it seconds later.

Miss Montague, he learned, had no mother. Of course, she corrected herself, she did have a mother once but she died of neglect. Or incompetence. No-one really knew the truth of the matter. Her Mama had developed an infection from a cut and went to see the white doctor, at the government hospital. Everybody said she should have gone to the Japanese doctor but her Dada wouldn’t hear of it. Dada said that Asian people were inferior to white people and he wouldn’t fall so low as to allow his wife to be treated by an immigrant. But the white doctor was busy with the divers who needed to be passed fit to work – even though some of them weren’t – and there was lots of paperwork to fill in. So, he forgot about her Mama, and the infection spread and Mama died. Now Miss Montague was alone with darling Dada, who still hated the Asians, the mixed-race people, the poor whites and the Aborigines. Dada was thrilled that the white divers had arrived to swell their number. He had said so at breakfast.

They clattered down the backstreets past a maze of whitewashed iron-and-timber constructions and houses so jammed together that a stray lit match would have torched the lot. Rows of shops with fronts opening straight onto the road were cluttered with cheap merchandise, and everything for sale was being peddled by bawling tradesmen. It reeked of spicy food, fish, frying onions and the sickening odour of insanitation. Cooper tried to breathe through his mouth as they slowed for a corner, his ears ringing with horses’ hooves and the echo of underprivilege.

He craned his neck. ‘What’s going on over there, Miss Montague?’

A line of Aboriginal men was approaching, each one barefoot, the whole pageant trudging one behind the other in a dejected convoy. At the head of the column a white policeman in a heavy twill uniform shouldered a rifle, whistling idly, keeping himself company. The black men behind him, each wearing nothing but a loincloth, were skeletally thin, their ribs sticking out like toast racks. They were tethered together by steel neck chains.

Miss Montague halted the horse and turned to her companion. ‘Those are the Abos who spread the white shell-grit on the roads. You should see them later on when they’ve finished for the day. They get covered in white dust and gleam in the dark like ghosts. It’s terribly spooky!’

‘Why are they chained up?’

‘There’s only one warder for all the prisoners. How else is he going to control them?’

Cooper didn’t understand. ‘But why are there so many of them?’

‘I think someone once calculated that you need fifty men to build a road, so they try to keep the numbers up.’

‘What did they do?’

She shook up the reins. ‘Killing cattle, mainly. The Abos are quite docile really, until they’re hungry or full of drink. Then it’s a different story. But I think they have quite a nice life as prisoners. Dada says some of them get themselves caught on purpose. They are fed three times a day and the gaoler’s wife cooks them treats from time to time. They get two hours off at lunchtime and then a swim in the creek after work to get the dust off.’

‘Are neck chains used for European prisoners?’