Commodore Paul Jones

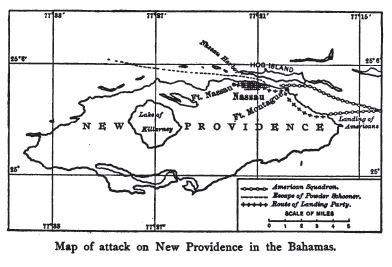

Preparations for attack were quickly made. Commodore Hopkins, having impressed some local schooners, loaded them with two hundred and fifty marines from the squadron, under the command of Captain Samuel Nichols, the ranking officer of the corps, and fifty seamen under the command of Lieutenant Thomas Weaver of the Cabot, and on March 2d the transports with this attacking force were dispatched to New Providence.3 They were convoyed by the Providence and the Wasp, and a landing was effected under the cover of these two ships of war. Unfortunately, however, some of the other larger vessels got under way at the same time, and their appearance alarmed the town.

It never seems to have occurred to any one but Jones that the west exit from the harbor should be guarded by stationing two of the smaller vessels off the channel to close it while the rest of the squadron took care of the eastern end. It seems probable from his correspondence that he ventured upon the suggestion, for he specifically referred in condemnatory terms to the failure to do so. At any rate, if he did suggest it, and from his known capacity it is extremely likely that the obvious precaution would have occurred to him, his suggestion was disregarded, and the western pass from the harbor was left open-a fatal mistake.

The point where the expedition landed without opposition was some four and a half miles from Fort Montague. It was a bright Sunday morning when the first American naval brigade took up its march under Captain Nichols' orders. The men advanced steadily, and, though they were met by a discharge of cannon from Fort Montague, they captured the works by assault without loss, the militia garrison flying precipitately before the American advance. The marines behaved with great spirit on this occasion, as they have ever done. Instead of promptly moving down upon the other fort, however, they contented themselves during that day with their bloodless achievement, and not until the next morning did they advance to complete the capture of the place.

The inhabitants of the island were in a state of panic, and when the marines and sailors marched up to attack Fort Nassau they found it empty of any garrison except Governor Brown, who opened the gates and formally surrendered it to the Americans. During the confusion of the night Brown seems to have preserved his presence of mind, and rightly divining that the powder would be the most precious of all the munitions of warfare in his charge, he had caused a schooner which lay in the harbor to be loaded with one hundred and fifty barrels, the limit of its capacity, and before daybreak she set sail and made good her escape through the unguarded western passage. A dreadful misfortune that, which would not have occurred had Jones been in command.

However, a large quantity of munitions of war of great value to the struggling colonies fell into the hands of Hopkins' men, including eighty-eight cannon, ranging in size from 9- to 36-pounders, fifteen large mortars, over eleven thousand round shot, and twenty precious casks of powder. The Americans behaved with great credit in this conquest. None of the inhabitants of the island were harmed, nor was their property touched. It was a noble commentary on some of the British forays along our own coast. Hopkins impressed a sloop, promising to pay for its use and return it when he was through with it, which promise was faithfully kept, and the sloop was loaded with the stores, etc., which had been captured.

His own ships were also heavily laden with these military stores, the Alfred in particular being so overweighted that it was almost impossible to fight her main-deck guns, so near were they to the waterline, except in the most favorable circumstances of wind and weather.

Taking Governor Brown, who was afterward exchanged for General Lord Stirling, and one or two other officials of importance as hostages on board his fleet, Hopkins set sail for home on the 17th of March. He had done his work expeditiously and well, but through want of precaution which had been suggested by Jones, he had failed in part when his success might have been complete. Still, he was bringing supplies of great value, and his handsome achievement was an auspicious beginning of naval operations. The squadron pursued its way toward the United Colonies without any adventures or happenings worthy of chronicle until the 4th of April, when off the east end of Long Island they captured the schooner Hawk, carrying six small guns. On the 5th of April the bomb vessel Bolton, eight guns, forty-eight men, filled with stores of arms and powder, was captured without loss.

On the 6th, shortly after midnight, the night being dark, the wind gentle, the sea smooth, and the ships very much scattered, swashing along close-hauled on the starboard tack between Block Island and the Rhode Island coast, they made out a large ship, under easy sail, coming down the wind toward the squadron. It was the British sloop of war Glasgow, twenty guns and one hundred and fifty men, commanded by Captain Tyringham Howe. She was accompanied by a small tender, subsequently captured. The nearest ships of the American squadron luffed up to have a closer look at the stranger, the men being sent to quarters in preparation for any emergency. By half after two in the morning the brig Cabot had come within a short distance of her. The stranger now hauled her wind, and Captain John Burroughs Hopkins, the son of the commodore, immediately hailed her. Upon ascertaining who and what she was he promptly poured in a broadside from his small guns, which was at once returned by the formidable battery of the Glasgow. The unequal conflict was kept up with great spirit for a few moments, but the Cabot alone was no match for the heavy English corvette, and after a loss of four killed and several wounded, including the captain severely, the Cabot, greatly damaged in hull and rigging, fell away, and her place was taken by the Alfred, still an unequal match for the English vessel, but more nearly approaching her size and capacity.

The Andrea Doria now got within range and joined in the battle. For some three hours in the night the ships sailed side by side, hotly engaged. After a time the Columbus, Captain Whipple, which had been farthest to leeward, succeeded in crossing the stern of the Glasgow, and raked her as she was passing. The aim of the Americans was poor, and instead of smashing her stern in and doing the damage which might have been anticipated, the shot flew high and, beyond cutting the Englishman up aloft, did no appreciable damage. The Providence, which was very badly handled, managed to get in long range on the lee quarter of the Glasgow and opened an occasional and ineffective fire upon her. But the bulk of the fighting on the part of the Americans was done by the Alfred.

Captain Howe maneuvered and fought his vessel with the greatest skill. During the course of the action a lucky shot from the Glasgow carried away the wheel ropes of the Alfred, and before the relieving tackles could be manned and the damage repaired the American frigate broached to and was severely raked several times before she could be got under command. At daybreak Captain Howe, who had fought a most gallant fight against overwhelming odds, perceived the hopelessness of continuing the combat, and, having easily obtained a commanding lead on the pursuing Americans, put his helm up and ran away before the wind for Newport.

Hopkins followed him for a short distance, keeping up a fire from his bow-chasers, but his deep-laden merchant vessels were no match in speed for the swift-sailing English sloop of war, and, as with every moment his little squadron with its precious cargo was drawing nearer the English ships stationed at Newport, some of which had already heard the firing and were preparing to get under way, Hopkins hauled his wind, tacked and beat up for New London, where he arrived on the 8th of April with his entire squadron and the prizes they had taken, with the exception of the Hawk, recaptured.

The loss on the Glasgow was one man killed and three wounded; on the American squadron, ten killed and fourteen wounded, the loss being confined mainly to the Alfred and the Cabot, the Columbus having but one man wounded. During this action Paul Jones was stationed in command of the main battery of the Alfred. He had nothing whatever to do with the maneuvers of the ships, and was in no way responsible for the escape of the Glasgow and the failure of the American force to capture her.

The action did not reflect credit on the American arms. The Glasgow, being a regular cruiser and of much heavier armament than any of the American ships, was more than a match for any of them singly, though taken together, if the personnel of the American squadron had been equal to, or if it even approximated, that of the British ship, the latter would have been captured without difficulty. The gun practice of the Americans was very poor, which is not surprising. With the exception of a very few of the officers, none of the Americans had ever been in action, and they knew little about the fine art of hitting a mark, especially at night. They had had no exercise in target practice and but little in concerted fleet evolution. There seems to have been no lack of courage except in the case of the captain of the Providence, who was court-martialed for incapacity and cowardice, and dismissed from the service. Hopkins' judgment in withdrawing from the pursuit for the reasons stated can not be questioned, neither can he be justly charged with the radical deficiency of the squadron, though he was made to suffer for it.

While the Glasgow escaped, she did not get off scot free. She was badly cut up in the hull, had ten shot through her mainmast, fifty-two through her mizzen staysail, one hundred and ten through her mainsail, and eighty-eight through her foresail. Her royal yards were carried away, many of her spars badly wounded, and her rigging cut to pieces. This catalogue tells the story. The Americans in their excitement and inexperience had fired high, and their shot had gone over their mark. The British defense had been a most gallant one, and the first attack between the ships of the two navies had been a decided triumph for the English.

Paul Jones' conduct in the main battery of the Alfred had been entirely satisfactory to his superior officers. He, with the other officers of that ship, was commended, and subsequent events showed that he still held the confidence of the commodore.

CHAPTER III

THE CRUISE OF THE PROVIDENCE

The British fleet having left Newport in the interim, on the 24th of April, 1776, the American squadron got under way from New London for Providence, Rhode Island. The ships were in bad condition; sickness had broken out among their crews, and no less than two hundred and two men out of a total of perhaps eight hundred and fifty-at best an insufficient complement-were left ill at New London. Their places were in a measure supplied by one hundred and seventy soldiers, lent to the squadron by General Washington, who had happened to pass through New London, en route to New York, on the day after Hopkins' arrival. There was a pleasant interview between the two commanders, and it was then that Jones caught his first glimpse of the great leader.

The voyage to New London was made without incident, except that the unfortunate Alfred grounded off Fisher's Island, and had to lighten ship before she could be floated. This delayed her passage so that she did not arrive at Newport until the 28th of April. The health of the squadron was not appreciably bettered by the change, for over one hundred additional men fell ill. Many of the seamen had been enlisted for the cruise only, and they now received their discharge, so that the crews of the already undermanned ships were so depleted from these causes that it would be impossible for them to put to sea. Washington, who was hard pressed for men, and had troubles of his own, demanded the immediate return to New York of the soldiers he had lent to the fleet. The captain of the Providence being under orders for a court-martial for his conduct, on the 10th of May Hopkins appointed John Paul Jones to the command of the Providence.

The appointment is an evidence of the esteem in which Jones was held by his commanding officer, and is a testimony to the confidence which was felt in his ability and skill; for he alone, out of all the officers in the squadron, was chosen for important sea service at this time. Having no blank commissions by him, Hopkins made out the new commission on the back of Jones' original commission as first lieutenant. It is a matter of interest to note that he was the first officer promoted to command rank from a lieutenancy in the American navy. His first orders directed him to take Washington's borrowed men to New York. After spending a brief time in hurriedly overhauling the brig and preparing her for the voyage, Jones set sail for New York, which he reached on the 18th of May, after thirty-six hours. Having returned the men, Jones remained at New York in accordance with his orders until he could enlist a crew, which he presently succeeded in doing. Thereafter, under supplemental orders, he ran over to New London, took on board such of the men left there who were sufficiently recovered to be able to resume their duties, and came back and reported with them to the commander-in-chief at Providence. He had performed his duties, routine though they were, expeditiously and properly.

He now received instructions thoroughly to overhaul and fit the Providence for active cruising. She was hove down, had her bottom scraped, and was entirely refitted and provisioned under Jones's skillful and practical direction. Her crew was exercised constantly at small arms and great guns, and every effort made to put her in first-class condition. In spite of the limited means at hand, she became a model little war vessel. On June 10th a sloop of war belonging to the enemy appeared off the bay, and in obedience to a signal from the commodore Jones made sail to engage. Before he caught sight of the vessel she sought safety in flight. On the 13th of June the Providence was ordered to Newburyport, Massachusetts, to convoy a number of merchant vessels loaded with coal for Philadelphia. Before entering upon this important duty, however, Jones was directed to accompany the tender Fly, loaded with cannon, toward New York, and, after seeing her safely into the Sound, convoy some merchant vessels from Stonington to Newport.

There were a number of the enemy's war vessels cruising in these frequented waters, and the carrying out of Jones' simple orders was by no means an easy task; but by address and skill, and that careful watchfulness which even then formed a part of his character, he succeeded in executing all his duties without losing a single vessel under his charge. He had one or two exciting encounters with English war ships, the details of which are unfortunately not preserved. In one instance, by boldly interposing the Providence between the British frigate Cerberus and a colonial brigantine loaded with military stores from Hispaniola, he diverted the attention of the frigate to his own vessel, and drew her away from the pursuit of the helpless merchantman, which thereby effected her escape. Then the Providence, a swift little brig admirably handled, easily succeeded in shaking off her pursuer, although she had allowed the frigate to come within gunshot range. The brigantine whose escape Jones had thus assured was purchased into the naval service and renamed the Hampden.

The coal fleet had assembled at Boston instead of Newburyport, and in pursuance of his original orders Jones brought them safely to the capes of the Delaware on the 1st of August. The run to Philadelphia was soon made, and Hopkins' appointment, under which he was acting, was ratified by the Congress, and the commission of captain was given him, dated the 8th of August, 1776.

Hitherto Jones, like all the others engaged in the war, had been a subject of England, a colonist in rebellion against the crown. By the Declaration of Independence he had become a citizen of the United States engaged in maintaining the independence and securing the liberty of his adopted country. The change was most agreeable to him. It added a dignity and value to his commission which could not fail to be acceptable to a man of his temperament. It was pleasant to him also to have the confidence of his commander-in-chief, which had been shown in the appointment to the command of the Providence, justified by the government in the commission which had been issued to him.

Jones had made choice of his course of action in the struggle between kingdom and colony deliberately, not carried away by any enthusiasm of the moment, but moved by the most generous sentiments of liberty and independence. He had much at stake, and he was embarked in that particular profession fraught with peculiar dangers not incident to the life of a soldier. It must have been, therefore, with the greatest satisfaction that he perceived opportunities opening before him in that cause to which he had devoted himself, and in that service of which he was a master. A foreigner with but scant acquaintance and little influence in America, he had to make his way by sheer merit. The value of what has been subsequently called "a political pull" with the Congress was as well known then as it is now, and nearly as much used, too. He practically had none. Nevertheless, his foot was already upon that ladder upon which he intended to mount to the highest round eventually. He was not destined to realize his ambition, however, without a heartbreaking struggle against uncalled-for restraint, and a continued protest against active injustice which tried his very soul.

It was first proposed by the Marine Committee that he return to New England and assume command of the Hampden, but he wisely preferred to remain in the Providence for the time being. He thoroughly knew the ship and the crew, over which he had gained that ascendency he always enjoyed with those who sailed under his command. Not so much by mistaken kindness or indulgence did he win the devotion of his men-for he was ever a stern and severe, though by no means a merciless, disciplinarian-but because of his undoubted courage, brilliant seamanship, splendid audacity, and uniform success. There is an attraction about these qualities which is exercised perhaps more powerfully upon seamen than upon any other class. The profession of a sailor is one in which immediate decision, address, resource, and courage are more in evidence than in any other. The seaman in an emergency has but little time for reflection, and in the hour of peril, when the demand is made upon him, he must choose the right course instantly-as it were by instinct.

With large discretion in his orders, which were practically to cruise at pleasure and destroy the enemy's commerce, the Providence left the Delaware on the 21st of August. In the first week of the cruise she captured the brigs Sea Nymph, Favorite, and Britannia; the first two laden with rum, sugar, etc., and the last a whaler. These rich prizes were all manned and sent in.

On the morning of the 1st of September, being in the latitude of the Bermudas, five vessels were sighted to leeward. The sea was moderately smooth, with a fresh breeze blowing at the time, and the Providence immediately ran off toward the strangers to investigate. It appeared to the observers on Jones' brig that the largest was an East Indiaman and the others ordinary merchant vessels. They were in error, however, in their conclusions, for a nearer approach disclosed the fact that the supposed East Indiaman was a frigate of twenty-eight guns, called the Solebay. Jones immediately hauled his wind and clapped on sail. The frigate, which had endeavored to conceal her force with the hope of enticing the Providence under her guns, at once made sail in pursuit. The Providence was a smart goer, and so was the Solebay. The two vessels settled down for a long chase. On the wind it became painfully evident that the frigate had the heels of the brig. With burning anxiety Jones and his officers saw the latter gradually closing with them. Shot from her bow-chasers, as she came within range, rushed through the air at the little American sloop of war, which now hoisted her colors and returned the fire. Seeing this, the Solebay set an American ensign, and fired one or two guns to leeward in token of amity, but Jones was not to be taken in by any transparent ruse of this character. He held on, grimly determined. As the Solebay drew nearer she ceased firing, confident in her ability to capture the chase, for which, indeed, there appeared no escape.

An ordinary seaman, even though a brave man, would probably have given up the game in his mind, though his devotion to duty would have compelled him to continue the fight until actually overhauled, but Jones had no idea of being captured then. Already a plan of escape had developed in his fertile brain. Communicating his intentions to his officers, he completed his preparations, and only awaited the favorable moment for action. The Solebay had crept up to within one hundred yards of the lee quarter of the Providence. If the frigate yawed and delivered a broadside the brig would be sunk or crippled and captured. Now was the time, if ever, to put his plan in operation. If the maneuver failed, it would be all up with the Americans. As usual, Jones boldly staked all on the issue of the moment. As a preliminary the helm had been put slightly a-weather, and the brig allowed to fall off to leeward a little, so bringing the Solebay almost dead astern-if anything, a little to windward. In anticipation of close action, as Jones had imagined, the English captain had loaded his guns with grape shot, which, of course, would only be effective at short range. Should the Englishman get the Providence under his broadside, a well-aimed discharge of grape would clear her decks and enable him to capture the handsome brig without appreciably damaging her.

From his knowledge of the qualities of the Providence, Jones felt sure that going free-that is, with the wind aft, or on the quarter-he could run away from his pursuer. The men, of course, had been sent to their stations long since. The six 4-pounders, which constituted the lee battery, were quietly manned, the guns being double-shotted with grape and solid shot. The studding sails-light sails calculated to give a great increase in the spread of canvas to augment the speed of the ship in a light breeze, which could be used to advantage going free and in moderate winds-were brought out and prepared for immediate use. Everything having been made ready, and the men cautioned to pay strict attention to orders, and to execute them with the greatest promptitude and celerity, Jones suddenly put his helm hard up.

The handy Providence spun around on her heel like a top, and in a trice was standing boldly across the forefoot of the onrushing English frigate. When she lay squarely athwart the bows of the Solebay Jones gave the order to fire, and the little battery of 4-pounders barked out its gallant salute and poured its solid shot and grape into the eyes of the frigate. In the confusion of the moment, owing to the suddenness of the unexpected maneuver, and the raking he had received, the English captain lost his head. Before he could realize what had happened, the Providence, partially concealed by the smoke from her own guns, had drawn past him, and, covered with great wide-reaching clouds of light canvas by the nimble fingers of her anxious crew, was ripping through the water at a great rate at a right angle to her former direction.

When the Solebay, rapidly forging ahead, crossed the stern of the saucy American a few moments after, she delivered a broadside, which at that range, as the guns were loaded with grape shot, did little damage to the brig and harmed no one. The distance was too great and the guns were badly aimed. By the time the Solebay had emulated the maneuvers of the Providence and had run off, the latter had gained so great a lead that her escape was practically effected. The English frigate proved to be unable to outfoot the American brig on this course, and after firing upward of a hundred shot at her the Solebay gave over the pursuit. This escape has ever been counted one of the most daring and subtle pieces of seamanship and skill among the many with which the records of the American navy abound. As subsequent events proved, the failure to capture Jones was most unfortunate on the part of the English.