Commodore Paul Jones

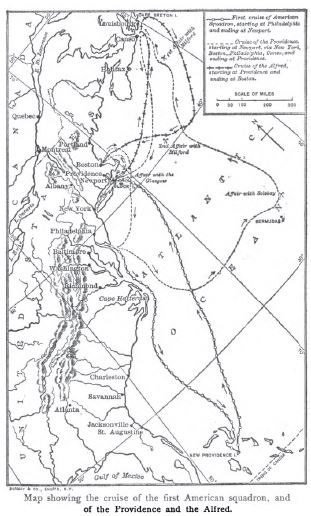

Jones now shaped his course for the Banks of Newfoundland, to break up the fishing industry and let the British know that ravaging the coast, which they had begun, was a game at which two could play. On the 16th and 17th of the month he ran into a heavy gale, so severe in character that he was forced to strike his guns into the hold on account of the rolling of the brig. The gale abated on the 19th, and on the 20th of September, the day being pleasant, the Providence was hove to and the men were preparing to enjoy a day of rest and amusement, fishing for cod, when in the morning two sail appeared to windward. As Jones was preparing to beat up and investigate them, they saved him that trouble by changing their course and running down toward him. They proved to be a merchant ship and a British frigate, the Milford, 32.

Jones kept the Providence under easy canvas until he learned the force of the enemy, and then made all sail to escape. Finding that he was very much faster than his pursuer, he amused himself during one whole day by ranging ahead and then checking his speed until the frigate would get almost within range, when he would run off again and repeat the performance. It was naturally most tantalizing to the officers of the Milford, and they vented their wrath in futile broadsides whenever there appeared the least possibility of reaching the Providence. After causing the enemy to expend a large quantity of powder and shot, having tired of the game, Jones contemptuously discharged a musket at them and sailed away.

On the 21st of September he appeared off the island of Canso, one of the principal fishing depots of the Grand Banks. He sent his boat in that night to gain information, and on the 22d he anchored in the harbor. There were three fishing schooners there, one of which he burned, one he scuttled, and the third, called the Ebenezer, he loaded with the fish taken from the two he had destroyed, and manned as a prize. After replenishing his wood and water, on the 23d he sailed up to Isle Madame, having learned that the fishing fleet was lying there dismantled for the winter. Beating to and fro with the Providence off the island, on that same evening he sent an expedition of twenty-five men in a shallop which he had captured at Canso, accompanied by a fully manned boat from the Providence. Both crews were heavily armed. The expedition captured the fishing fleet of nine vessels without loss. The crews of most of them, numbering some three hundred men, were ashore at the time, and the vessels were dismantled. Jones promised that if the men ashore would help to refit the vessels he desired to take with him as prizes, he would leave them a sufficient number of boats to enable them to regain their homes. By his ready address he actually persuaded them to comply with his request, and the unfortunate Englishmen labored assiduously to get the ships ready for sea.

On the 25th of September their preparations were completed, but a violent autumn gale blew up, and their situation became one of great peril. The Providence, anchored in Great St. Peter Channel, rode it out with two anchors down to a long scope of cable. The ship Alexander and the schooner Sea Flower, which were heavily laden with valuable plunder, had also reached the same channel. The Alexander succeeded in making an anchorage under a point of rocks which sheltered her, and enabled her to sustain the shock of the gale unharmed. The Sea Flower was driven on the lee shore, and, being hopelessly wrecked, was scuttled and fired the next day. The Ebenezer, loaded with fish from Canso, was also wrecked. The gale had abated about noon, when, after burning the ship Adventure, dismantled and in ballast, and leaving a brig and two small schooners to enable the English seamen to reach home, the Providence, accompanied by the Alexander and the brigs Kingston Packet and Success, got under way for home. On the 27th the Providence, in spite of the fact that she was now very short-handed on account of the several prizes she had manned, chased two armed transports apparently bound in for Quebec, which managed to make good their escape. The little squadron resumed its course, and arrived safely at Rhode Island without further mishap on the 7th of October.

On this remarkable cruise Jones had captured sixteen vessels, eight of which he manned and sent in as prizes, destroying five of the remainder, and generously leaving three for the unfortunate fishermen to reach their homes. He had carried out his orders to sink, burn, destroy, and capture with characteristic thoroughness, but without needless cruelty and oppression. He burned no dwelling houses, and turned no non-combatants out of their homes in the middle of winter, as Mowatt had done at Falmouth. He had entirely broken up the fishery at Canso, had escaped by the exercise of the highest seamanship from one British frigate, and had led another a merry dance in impotent pursuit. Property belonging to the enemy had been destroyed to the value of perhaps a million of dollars in round numbers, not to speak of the effect upon their pride by the bold cruising of the little brig of twelve 4-pound guns and seventy men.

CHAPTER IV

THE CRUISE OF THE ALFRED

When his countrymen heard the story of this daring and successful cruise, Jones immediately became the most famous officer of the new navy. The éclat he had gained by his brilliant voyage at once raised him from a more or less obscure position, and gave him a great reputation in the eyes of his countrymen, a reputation he did not thereafter lose. But Jones was not a man to live upon a reputation. He had scarcely arrived at Providence before he busied himself with plans for another undertaking. He had learned from prisoners taken on his last cruise that there were a number of American prisoners, at various places, who were undergoing hard labor in the coal mines of Cape Breton Island, and he conceived the bold design of freeing them if possible.

We are here introduced to one striking characteristic, not the least noble among many, of this great man. The appeal of the prisoner always profoundly touched his heart. The freedom of his nature, his own passionate love for liberty and independence, the heritage of his Scotch hills perhaps, ever made him anxious and solicitous about those who languished in captivity. It was but the working out of that spirit which compelled him to relinquish his participation in the lucrative slave trade. In all his public actions, he kept before him as one of his principal objects the release of such of his countrymen as were undergoing the horrors of British prisons.

The suggested enterprise found favor in the mind of Commodore Hopkins, who forthwith assigned Jones to the command of a squadron comprising the Alfred, the Providence, and the brigantine Hampden. Jones hoisted his flag on board the Alfred and hastened his preparations for departure. He found the greatest difficulty in manning his little squadron, and finally, in despair of getting a sufficient crew to man them all, he determined to set sail with the Alfred and the Hampden only, the latter vessel being commanded by Captain Hoysted Hacker. He received his orders on the 22d of October, and on the 27th the two vessels got under way from Providence. The wind was blowing fresh at the time, and Hacker, who seems to have been an indifferent sailor, ran the Hampden on a ledge of rock, where she was so badly wrecked as to be unseaworthy. Jones put back to his anchorage, and, having transferred the crew of the Hampden to the Providence, set sail on the 2d of November.

Both vessels were very short-handed. The Alfred, whose proper complement was about three hundred, which had sailed from Philadelphia with two hundred and thirty-five, now could muster no more than one hundred and fifty all told. The two vessels were short of water, provisions, munitions, and everything else that goes to make up a ship of war. Jones made up for all this deficiency by his own personality.

On the evening of the first day out the two vessels anchored in Tarpauling Cove, near Nantucket. There they found a Rhode Island privateer at anchor. In accordance with the orders of the commodore, Jones searched her for deserters, and from her took four men on board the Alfred. He was afterward sued in the sum of ten thousand pounds for this action, but, though the commodore, as he stated, abandoned him in his defense, nothing came of the suit.

On the 3d of November, by skillful and successful maneuvering, the two ships passed through the heavy British fleet off Block Island, and squared away for the old cruising ground on the Grand Banks. In addition to the release of the prisoners there was another object in the cruise. A squadron of merchant vessels loaded with coal for the British army in New York was about to leave Louisburg under convoy. Jones determined to intercept them if possible.

On the 13th, off Cape Canso again, the Alfred encountered the British armed transport Mellish, of ten guns, having on board one hundred and fifty soldiers. After a trifling resistance she was captured. She was loaded with arms, munitions of war, military supplies, and ten thousand suits of winter clothing, destined for Sir Guy Carleton's army in Canada. She was the most valuable prize which had yet fallen into the hands of the Americans. The warm clothing, especially, would be a godsend to the ragged, naked army of Washington. Of so much importance was this prize that Jones determined not to lose sight of her, and to convoy her into the harbor himself. Putting a prize crew on board, he gave instructions that she was to be scuttled if there appeared any danger of her recapture.

About this time two other vessels were captured, one of which was a large fishing vessel, from which he was able to replenish his meager store of provisions. On the 14th of November a severe gale blew up from the northwest, accompanied by a violent snowstorm. Captain Hacker bore away to the southward before the storm and parted company during the night, returning incontinently to Newport. The weather continued execrable. Amid blinding snowstorms and fierce winter gales the Alfred and her prizes beat up along the desolate iron-bound shore. Jones again entered the harbor of Canso, and, finding a large English transport laden with provisions for the army aground on a shoal near the mouth of the harbor, sent a boat party which set her on fire. Seeing an immense warehouse filled with oil and material for whale and cod fisheries, the boats made a sudden dash for the shore, and, applying a torch to the building, it was soon consumed.

Beating off the shore, still accompanied by his prizes, he continued up the coast of Cape Breton toward Louisburg, looking for the coal fleet. It was his good fortune to run across it in a dense fog. It consisted of a number of vessels under the convoy of the frigate Flora, a ship which would have made short work of him if she could have run across him. Favored by the impenetrable fog, with great address and hardihood Jones succeeded in capturing no less than three of the convoy, and escaped unnoticed with his prizes.

Two days afterward he came across a heavily armed British privateer from Liverpool, which he took after a slight resistance. But now, when he attempted to make Louisburg to carry out his design of levying on the place and releasing the prisoners, he found that the harbor was closed by masses of ice, and that it was impossible to effect a landing. Indeed, his ships were in a perilous condition already. He had manned no less than six prizes, which had reduced his short crew almost to a prohibitive degree. On board the Alfred he had over one hundred and fifty prisoners, a number greatly in excess of his own men; his water casks were nearly empty, and his provisions were exhausted. He had six prizes with him, one of exceptional value. Nothing could be gained by lingering on the coast, and he decided, therefore, to return.

The little squadron, under convoy of the Alfred and the armed privateer, which he had manned and placed under the command of Lieutenant Saunders, made its way toward the south in the fierce winter weather. Off St. George's Bank they again encountered the Milford. It was late in the afternoon when her topsails rose above the horizon. The wind was blowing fresh from the northwest; the Alfred and her prizes were on the starboard tack, the enemy was to windward. From his previous experience Jones was able fairly to estimate the speed of the Milford. A careful examination convinced him that it would be impossible for the latter to close with his ships before nightfall. He therefore placed the Alfred and the privateer between the English frigate lasking down upon them and the rest of his ships, and continued his course. He then signaled the prizes, with the exception of the privateer, that they should disregard any orders or signals which he might give in the night, and hold on as they were.

The prizes were slow sailers, and, as the slowest necessarily set the pace for the whole squadron, the Milford gradually overhauled them. At the close of the short winter day, when the night fell and the darkness rendered sight of the pursued impossible, Jones showed a set of lantern signals, and, hanging a top light on the Alfred, right where it would be seen by the Englishmen, at midnight, followed by the privateer, he changed his course directly away from the prizes. The Milford promptly altered her course and pursued the light. The prizes, in obedience to their orders, held on as they were. At daybreak the prizes were nowhere to be seen, and the Milford was booming along after the privateer and the Alfred.

To run was no part of Paul Jones' desires, and he determined to make a closer inspection of the Milford, with a view to engaging if a possibility of capturing her presented itself; so he bore up and headed for the oncoming British frigate. The privateer did the same. A nearer view, however, developed the strength of the enemy, and convinced him that it would be madness to attempt to engage with the Alfred and the privateer in the condition he then was, so he hauled aboard his port tacks once more, and, signaling to the privateer, stood off again. For some reason-Jones imagined that it was caused by a mistaken idea of the strength of the Milford-Saunders signaled to Jones that the Milford was of inferior force, and disregarding his orders foolishly ran down under her lee from a position of perfect safety, and was captured without a blow. The lack of proper subordination in the nascent navy of the United States brought about many disasters, and this was one of them. Jones characterized this as an act of folly; it is difficult to dismiss it thus mildly. I would fain do no man an injustice, but if a man wanted to be a traitor that is the way he would act. Jones' own account of this adventure, which follows, is of deep interest:

"This led the Milford entirely out of the way of the prizes, and particularly the clothing ship, Mellish, for they were all out of sight in the morning. I had now to get out of the difficulty in the best way I could. In the morning we again tacked, and as the Milford did not make much appearance I was unwilling to quit her without a certainty of her superior force. She was out of shot, on the lee quarter, and as I could only see her bow, I ordered the letter of marque, Lieutenant Saunders, that held a much better wind than the Alfred, to drop slowly astern, until he could discover by a view of the enemy's side whether she was of superior or inferior force, and to make a signal accordingly. On seeing Mr. Saunders drop astern, the Milford wore suddenly and crowded sail toward the northeast. This raised in me such doubts as determined me to wear also, and give chase. Mr. Saunders steered by the wind, while the Milford went lasking, and the Alfred followed her with a pressed sail, so that Mr. Saunders was soon almost hull down to windward. At last the Milford tacked again, but I did not tack the Alfred till I had the enemy's side fairly open, and could plainly see her force. I then tacked about ten o'clock. The Alfred being too light to be steered by the wind, I bore away two points, while the Milford steered close by the wind, to gain the Alfred's wake; and by that means he dropped astern, notwithstanding his superior sailing. The weather, too, which became exceedingly squally, enabled me to outdo the Milford by carrying more sail. I began to be under no apprehension from the enemy's superiority, for there was every appearance of a severe gale, which really took place in the night. To my great surprise, however, Mr. Saunders, toward four o'clock, bore down on the Milford, made the signal of her inferior force, ran under her lee, and was taken!"

With the exception of one small vessel, which was recaptured, the prizes all arrived safely, the precious Mellish finally reaching the harbor of Dartmouth. The Alfred dropped anchor at Boston, December 15, 1776. The news of the captured clothing reached Washington and gladdened his heart-and the hearts of his troops as well-on the eve of the battle of Trenton.

The reward for this brilliant and successful cruise, the splendid results of which had been brought about by the most meager means, was an order relieving him of the command of the Alfred and assigning him to the Providence again. When he arrived at Philadelphia the next spring he found that by an act of Congress, on the 10th of October, 1776, which had created a number of captains in the navy, he, who had been first on the list of lieutenants, and therefore the sixth ranking sea officer, was now made the eighteenth captain. He was passed over by men who had no claim whatever to superiority on the score of their service to the Commonwealth, which had been inconsiderable or nothing at all. Indeed, there was no man in the country who by merit or achievement was entitled to precede him, except possibly Nicholas Biddle.

If the friendless Scotsman had commanded more influence, more political prestige, so that he might have been rewarded for his auspicious services by placing him at the head of the navy, I venture to believe that some glorious chapters in our marine history would have been written.

CHAPTER V

SUPERSEDED IN RANK-PROTESTS VAINLY AGAINST THE INJUSTICE-ORDERED TO COMMAND THE RANGER-HOISTS FIRST AMERICAN FLAG

The period between the termination of his last cruise and his assignment to his next important command was employed by Jones in vigorous and proper protests against the arbitrary action of Congress, which had deprived him of that position on the navy list which was his just due, were either merit, date of commission, or quality of service considered. To the ordinary citizen the question may appear of little interest, but to the professional soldier or sailor it is of the first importance. Indeed, it is impossible to conceive of properly maintaining an army or navy without regular promotion, definitive station, and adequate reward of merit. To feel that rank is temporary and position is at the will of unreasonable and irresponsible direction is to undermine service.

The same injustice drove John Stark, of New Hampshire, to resign the service with the pithy observation that an officer who could not protect his own rights was unfit to be trusted with those of his country. It did not prevent his winning the fight at Bennington, though. The same treatment caused Daniel Morgan to seek that retirement from which he was only drawn forth by his country's peril to win the Battle of the Cowpens. And, lastly, it was the same treatment which, in part at least, made Arnold a traitor. Then, as ever, Congress was continually meddling with matters of purely military administration, to the very great detriment of the service.

Jones has been censured as a jealous stickler for rank, a quibbler about petty distinctions in trying times. Such criticisms proceed from ignorance. If there were nothing else, rank means opportunity. The range of prospective enterprises is greater the higher the rank. The little Scotsman was properly tenacious of his prerogatives-we could not admire him if he were not so-and naturally exasperated by the arbitrary course of Congress, against which he protested with all the vehemence of his passionate, fiery, and-it must be confessed-somewhat irritable nature. On this subject he thus wrote to the Marine Board at Philadelphia:

"I am now to inform you that by a letter from Commodore Hopkins, dated on board the Warren, January 14, 1777, which came to my hands a day or two ago, I am superseded in the command of the Alfred, in favour of Captain Hinman, and ordered back to the sloop in Providence River. Whether this order doth or doth not supersede also your orders to me of the 10th ult. you can best determine; however, as I undertook the late expedition at his (Commodore Hopkins') request, from a principle of humanity, I mean not now to make a difficulty about trifles, especially when the good of the service is to be consulted. As I am unconscious of any neglect of duty or misconduct, since my appointment at the first as eldest lieutenant of the navy, I can not suppose that you have intended to set me aside in favour of any man who did not at that time bear a captain's commission, unless, indeed, that man, by exerting his superior abilities, hath rendered or can render more important services to America. Those who stepped forth at the first, in ships altogether unfit for war, were generally considered as frantic rather than wise men, for it must be remembered that almost everything then made against them. And although the success in the affair with the Glasgow was not equal to what it might have been, yet the blame ought not to be general. The principal or principals in command alone are culpable, and the other officers, while they stand unimpeached, have their full merit. There were, it is true, divers persons, from misrepresentation, put into commission at the beginning, without fit qualification, and perhaps the number may have been increased by later appointments; but it follows not that the gentleman or man of merit should be neglected or overlooked on their account. None other than a gentleman, as well as a seaman both in theory and practice, is qualified to support the character of a commission officer in the navy; nor is any man fit to command a ship of war who is not also capable of communicating his ideas on paper, in language that becomes his rank. If this be admitted, the foregoing operations will be sufficiently clear; but if further proof is required it can easily be produced.

"When I entered into the service I was not actuated by motives of self-interest. I stepped forth as a free citizen of the world, in defense of the violated rights of mankind, and not in search of riches, whereof, I thank God, I inherit a sufficiency; but I should prove my degeneracy were I not in the highest degree tenacious of my rank and seniority. As a gentleman I can yield this point up only to persons of superior abilities and superior merit, and under such persons it would be my highest ambition to learn. As this is the first time of my having expressed the least anxiety on my own account, I must entreat your patience until I account to you for the reason which hath given me this freedom of sentiment. It seems that Captain Hinman's commission is No. 1, and that, in consequence, he who was at first my junior officer by eight, hath expressed himself as my senior officer in a manner which doth himself no honour, and which doth me signal injury. There are also in the navy persons who have not shown me fair play after the service I have rendered them. I have even been blamed for the civilities which I have shown to my prisoners, at the request of one of whom I herein inclose an appeal, which I must beg leave to lay before Congress. Could you see the appellant's accomplished lady, and the innocents their children, arguments in their behalf would be unnecessary. As the base-minded only are capable of inconsistencies, you will not blame my free soul, which can never stoop where I can not also esteem. Could I, which I never can, bear to be superseded, I should indeed deserve your contempt and total neglect. I am therefore to entreat you to employ me in the most enterprising and active service, accountable to your honourable board only for my conduct, and connected as much as possible with gentlemen and men of good sense."

The letter does credit to his head and heart alike. Matter and manner are both admirable. In it he is at his best, and one paragraph shows that the generous sympathy he ever felt for a prisoner could even be extended to the enemies of his country, so that as far as he personally was concerned they should suffer no needless hardship in captivity. Considered as the production of a man whose life from boyhood had been mainly spent upon the sea in trading ships and slavers, with their limited opportunities for polite learning, and an entire absence of that refined society without which education rarely rises to the point of culture, the form and substance of Jones' letters are surprising. Of this and of most of the letters hereafter to be quoted only words of approbation may be used. A just yet modest appreciation of his own dignity, a proper and resolute determination to maintain it, a total failure to truckle to great men, an absence of sycophancy and hypocrisy, a clear insight into the requirements of a gentleman and an effortless rising to his own high standard without unpleasant self-assertion, are found in his correspondence. Considering the humble source from which he sprang, his words, written and spoken, equally with his deeds, indicate his rare qualities.