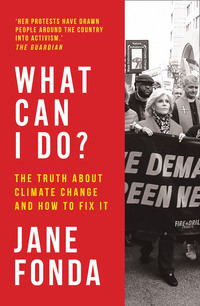

What Can I Do?

ALSO BY JANE FONDA

Jane Fonda’s Workout Book

Women Coming of Age (with Mignon McCarthy)

Jane Fonda’s New Workout & Weight-Loss Program

My Life So Far

Prime Time

Being a Teen: Everything Teen Girls & Boys Should Know About Relationships, Sex, Love, Health, Identity & More

Copyright

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2020

Copyright © Jane Fonda 2020

Jane Fonda asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Photograph Credits Pages 16, 161: courtesy of Jane Fonda; pages 79, 99, 214: courtesy of Madeline Carretero; pages 71, 82, 85, 86, 90, 91, 111: courtesy of Liz Gorman; page 324: courtesy of Vanessa Vadim; other photographs courtesy of Greenpeace/Tim Aubry

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

100% of the author’s net proceeds from What Can I Do? will go to Greenpeace

Ebook Edition © September 2020 ISBN: 9780008404611

Note to Readers

This ebook contains the following accessibility features which, if supported by your device, can be accessed via your ereader/accessibility settings:

Change of font size and line height

Change of background and font colours

Change of font

Change justification

Text to speech

Page numbers taken from the following print edition: ISBN 9780008404581

When I was young, I thought activism was a sprint,

and I worked around the clock, hoping for quick change.

When I was older, I learned activism is a marathon,

and I learned to pace myself.

At eighty-two, I realize it is neither sprint nor marathon;

it is a relay race. The most important thing we adults can do now

is join and support the next generation of climate activists

ready to lead the movement.

It is to them that I dedicate this book.

Contents

COVER

ALSO BY JANE FONDA

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

NOTE TO READERS

DEDICATION

CHAPTER ONE

The Wake-Up Call

CHAPTER TWO

The Launch

CHAPTER THREE

The Green New Deal

CHAPTER FOUR

Oceans and Climate Change

CHAPTER FIVE

Women and Climate Change

CHAPTER SIX

War, the Military, and Climate Change

CHAPTER SEVEN

Environmental Justice

CHAPTER EIGHT

Water and Climate Change

CHAPTER NINE

Plastics

CHAPTER TEN

Food, Agriculture, and Climate Change

CHAPTER ELEVEN

Climate, Migration, and Human Rights

CHAPTER TWELVE

Jobs and a Just Transition

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

Health and Climate Change

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

Forests and Climate Change

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

Holding the Fossil Fuel Industry Accountable

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

Stop the Money Pipeline

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

Fire Drill Fridays: Going Forward

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

APPENDIX A: AN INTRODUCTION TO UNDERSTANDING THE CLIMATE EMERGENCY

APPENDIX B: CIVIL DISOBEDIENCE

GREENPEACE NONVIOLENCE GUIDELINES

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

Jane sits with Annie at Greenpeace USA’s headquarters in Washington, D.C., at the very first Fire Drill Fridays planning meeting in September.

CHAPTER ONE

The Wake-Up Call

During Labor Day weekend in 2019, I was in Big Sur with my pals Catherine Keener and Rosanna Arquette. I have a history with Big Sur dating back to 1961, when I first ventured there by myself in search of Henry Miller. I had just read a pamphlet he wrote, To Paint Is to Love Again, and I wanted to meet him and talk. He wasn’t there, but I ended up spending a week at the hot springs (later to become Esalen), and it was transformative.

Now here I was once again in need of transformation. I’ve been an environmental activist since the 1970s, installing a windmill at my ranch in 1978 and solar heating and electricity in my Santa Monica home in 1981, speaking at rallies, attending Greenpeace marches in both the United States and Canada, and later getting an electric car, stopping my use of single-use plastic, recycling, and cutting back on red meat. But I was still ill at ease. Existential angst? I had just learned that there are 2.9 billion fewer birds in North America than there were in 1970; I knew that sea turtles are strangling from tumors caused by pollution in the oceans; whales are found dead with fifty pounds of plastic in their bellies; polar bears are starving; 93 percent of children worldwide are breathing polluted air that is endangering their health; and untold numbers of people were living in the midst of oil wells and refineries that were causing them major health problems. But I hadn’t really focused on what the scientists were saying.* I knew we needed to reduce fossil fuel use and invest in clean energy alternatives, fast, but these things remained a disturbing reality sitting out there somewhere, removed from me. I hadn’t taken it in and metabolized it. Instead, I would wonder if perhaps humankind deserved the fate it had created. I remembered what E. O. Wilson said decades ago, which I paraphrase: God granted the gift of intelligence to the wrong species. It should have gone to non-meat-eating creatures with no thumbs such as whales and dolphins. I agreed. Just get rid of us Homo sapiens ASAP and things will restore themselves.

But all the while, I knew this fatalist thinking was a cop-out, and I didn’t like myself for it. I’d be reminded of the recent birth of my grandson, and my two older grandkids, and the many people out there fighting for a better planet. No, fatalism couldn’t be for me. Yet I was compartmentalizing my grief rather than letting it into my heart.

Catherine Keener reminded me recently how, on the five-hour drive to Big Sur, she would go on an hourly rant: What can I do? Tell me what to do! Where are the leaders? I need someone to tell me what to do! I felt impotent, angry with myself for my inability to give her the answers she needed because I felt the same way. What can I do?

The very morning we left for Big Sur, I’d received an advance copy of Naomi Klein’s new book, On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New Deal. All my life, the exact book I needed without even knowing it had come to me at the perfect time and changed my trajectory. Here it was again. I began reading it the next day, and a quarter of the way through I was shaking with intensity.

Over time, I’ve asked myself what it was about Naomi’s book that so affected me. One was the way she wrote about Greta Thunberg, the sixteen-year-old Swedish activist who, in 2018, started a movement called Fridays for Future that had inspired school strikes for climate action around the world, involving millions of students. I knew about Greta. A lot had been written about her, including that she was on the autism spectrum. But until Naomi, I hadn’t understood what that had to do with the power of her connection to the climate crisis and the way she communicated about it. Naomi explained that unlike the rest of us, people with Asperger’s don’t look around and take cues about how to behave and feel from the people they see. They receive information pure and direct. If they study the science of climate change as Greta, a self-described science nerd, did, they aren’t able to read the stark facts, feel scared for a while, and then go about business as usual. When Greta, with her unfiltered focus, her inability to compartmentalize or cope with cognitive dissonance, read the science showing disaster was looming, she didn’t believe it at first. “It can’t be true, because, if it were, nobody would be speaking of anything else. All people would be doing is trying to figure out how to fix it.” But when she realized the science was true and nobody was behaving as they should in a crisis, she became traumatized. She stopped speaking and eating.

Reading this was like a kick in my stomach. I knew that what Greta had seen was the truth, that, as she said, we should be behaving as if our house were on fire, as if we were in a crisis, because we are. The brave, young student was exhorting us to get out of our comfort zone and do something. Learning this about Greta permitted me to take the science into my own body. This was the second thing in Naomi’s book that changed me: the clarity with which she conveyed what the scientists were saying in the 2018 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Virtually unanimously, the scientists make clear that given the worsening disasters we’re already seeing, and the additional warming that is already baked in because we didn’t act forty years ago, we don’t stand a chance at changing course in time without profound, systemic economic and social change, and they say, as of 2020, we have a brief ten years before the tipping point is reached. Ten years to reduce fossil fuel emissions roughly in half and then reduce to net zero by 2050 to avoid uncontrollable unraveling of the natural life-support system.

But the scientists also believe that we have the technology to make the transition in time to clean, renewable energy and that the most important factor in whether we can pull off what’s needed will be collective actions taken by social movements on an unprecedented scale. Social movements. In my fifty years of activism, I’d been part of social movements that changed policy. For instance, in 1972 and 1973, Tom Hayden, my second husband, and I launched the Indochina Peace Campaign, and together with scores of activists we crisscrossed the country educating the people whom the then president Richard Nixon described as the Silent Majority about the Vietnam War, the Pentagon Papers, and the need to cut the funding that was shoring up the government the United States had installed in South Vietnam that was keeping the war going. Especially because the just-released Pentagon Papers revealed that a succession of administrations had known we couldn’t win. The Pentagon Papers were to the Vietnam War what I think the IPCC 2018 report was to the climate crisis: irrefutable proof of lying and deceit on the part of people in power. In the end, the aid was cut, our client government collapsed, and the Vietnam War ended. Yes, I had experienced the effectiveness of mobilizing and organizing with a clear strategy and authoritative documents to back us up.

The third thing in Naomi’s book that struck me was how she explained the Green New Deal (GND). When Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Senator Ed Markey introduced the Green New Deal resolution in 2019, I thought including issues like low-carbon jobs and environmental and economic justice in a document about climate was taking it too far and would easily be dismissed by the right as a leftist wish list. But Naomi’s book made me understand justice is at the heart of solving what led to the climate crisis. The Green New Deal beckons us into a future where everyone can see a place for themselves.

When you’re famous, there are so many ways to lift issues and amplify voices. God knows I’ve done it before to varying degrees of success. But what can I do? What’s the right way to use my platform now, when things are getting worse fast?

Naomi’s book made clear that right now is the last possible moment in history when changing course can mean saving lives and species on an unimaginable scale. A true civilizational responsibility rests on our shoulders!

I knew what I needed to do, and I felt it so strongly I was quivering all over.

“I’m going to move to Washington, D.C., for a year and camp out in front of the White House to protest climate change,” I told Rosanna and Catherine over dinner at the Post Ranch Inn. “If Greta can do it, so can I.”

There, I’d said it to my pals, and now I couldn’t back out.

Being brave, gung ho gals, Catherine and Rosanna were all for it and pledged to join me when they could. Over the next few days we hiked, and I kept reading Naomi’s book. I felt more strongly that if I got the word out, others would join me. It had happened before during the later years of the Vietnam War. At night I lay in bed trying to remember where I’d stored my sleeping bag and bivy sack that have seen me through downpours and blizzards at fourteen thousand feet. I’ve done a lot of camping in my life and had all the right equipment, but I’d never camped in a city. Where will I poop and pee? I wondered. I’m way older now and have to get up during the night more often. Rosanna, Catherine, and I studied maps of D.C. trying to pick a spot where I would set up, but I realized I didn’t want a lonely vigil. What would be the point of that? I needed expert help to plan this. That’s when I tried to call Annie Leonard, the director of Greenpeace USA, because they were fearless supporters of big actions and, while I wasn’t certain, I felt my action might become big. I paced in front of Rosanna’s house, trying to get a phone signal, when I finally managed to reach her.

“Annie, it’s Jane Fonda here, do you have a minute? I have an idea and I need your advice.”

Annie assured me she did, so I rushed on. “I’m reading Naomi’s book, and I’ve decided to move to Washington for a year and camp out in front of the White House. I want to start in three weeks. Can you help me figure it out?” See, I’m someone who, when she gets an idea, is 100 percent ready to take a leap of faith and just do it. In fact, leaps of faith are my only form of exercise these days.

There was a rather long silence on Annie’s end, and then she said, “Well, Jane, that’s so wonderful and I’m blown away that you’re ready to put yourself out there like that, but, see, you can’t camp overnight in Washington anymore. It’s been made illegal after Occupy Wall Street camped there and more so in the current anti-protest climate in D.C. But let’s figure out what is possible.” She offered to set up a conference call with her, Bill McKibben, co-founder of 350.org, Naomi, the environmental lawyer Jay Halfon, and me. Time was of the essence, so Annie and I arranged to do the conference call the next day.

That day, Catherine, Rosanna, and I were visiting Esalen, the retreat center perched on twenty-seven acres of cliffs overlooking the Pacific. I figured Esalen would have decent reception for the conference call, and it felt appropriate that this possibly defining call would happen there. Generations of people seeking transformation often find themselves at Esalen, and the power it holds to create change is very much about its topography. It’s edgy. The sea off Big Sur is where the Arctic current meets the warm Pacific current. Land and sea touch each other at the base of jagged cliffs. It’s all the sharp edges and fierce winds, I think, that encourage people to break with their pasts, to look beyond dogma, and to examine new ways to be effective in the world. I remembered arriving there, a young woman in my midtwenties, the same age as many of the activists now driving the movement to stop climate change. Big Sur’s wild nature, those cliffs, was an important part of my transformation from child of the buttoned-up 1950s to someone who wanted to shake off the “good girl” shackles of my youth. In that way, it seemed right that I found myself in Esalen at this moment when I was rethinking how I could work to serve something larger than myself.

Turns out there was very poor cell phone service, but there was a bright red old-fashioned outdoor phone booth and a place where I could gather an hour’s worth of quarters.

Bill McKibben suggested that because camping was no longer permitted, perhaps a once-a-week protest that involved civil disobedience would be a better idea. Fridays had been claimed by Greta Thunberg and the student climate strikers, but the youth had also called on adults to join them. “Maybe you could do an action on Fridays as well.” Bill referenced what Randall Robinson, executive director of TransAfrica, had done in the mid-1980s, marching in front of the South African embassy in D.C. every day, committing civil disobedience by sitting down in the middle of Massachusetts Avenue, calling for freeing Nelson Mandela and ending apartheid in South Africa. “It was a very successful protest,” Bill said. In the beginning there were ten to twenty people, which grew to hundreds, and it spread nationwide until, in 1986, the first antiapartheid bill was passed in Congress.

Annie agreed, noting how important civil disobedience on behalf of climate has become. “For forty years, we’ve been polite, we’ve shared the science, we’ve petitioned, we’ve marched, rallied, written, pleaded. We’ve used all the levers of democracy available to us, and our elected representatives haven’t listened. Now we have to do more, step it up. Risk arrest if that is what it takes. It’s the fossil fuel industry who’ve led us to this. It’s time to be bold. Science demands it. Morality demands it. The moment demands it.”

Yes!

I dropped in more quarters and tried to breathe, not just because it was getting really hot in the phone booth, but because I could feel in my body that this was right. I was ready for this. I’d been getting ready for this my whole adult life … a weekly action that culminated in nonviolent civil disobedience. And I wouldn’t have to worry about pooping.

I wanted to start in a few weeks, so we decided I should go to D.C. as soon as possible to work out details and meet with some key environmental groups, including the student climate strikers, to get their input and buy-in. I began planning for the maximum time I could spend in D.C. before I had to get ready to film our seventh and last season of Grace and Frankie on January 27, 2020. It added up to four months, fourteen Fridays.

I started a list of the bare essentials I’d have to bring. I asked Debi Karolewski, who began assisting me in the early 1980s, to come with me. I knew I’d need my little dog Tulea, a fifteen-year-old Coton de Tulear. I couldn’t imagine being without her for four months. I also knew how sad I’d be to not see my two-and-a-half-month-old grandson, Leon, for that long.

I went about canceling everything on my schedule. Fortunately, I hadn’t booked any acting jobs during that time, but that also meant I had no source of income except a number of speaking gigs I had contracted for, and I soon realized they could sue me if I canceled them. Also, five of them were in and around Los Angeles with Lily Tomlin, and that would mean taking airplanes to and from Washington. Here I am, trying to reduce my carbon footprint, speaking out against fossil fuels, yet I’d be flying.

I spoke with Annie and several others about this contradiction. We weighed not flying against the possible good I could do in the climate movement by carrying out the Friday actions, and we concluded that the actions were more important. In the process of discussing this, I came to realize that as important as our individual lifestyle decisions are, they cannot be brought to scale in time to get us to where we need to be by 2030. I realized the importance of progress and not perfection. It’s structural change, new policies, that we need to focus on while at the same time continuing our individual commitments to the planet. Maybe the Friday actions would help bring about that policy change.

On September 27, en route to the Los Angeles airport with Debi, my little Tulea had a seizure. Tulea had already been diagnosed with an age-related enlarged heart and damaged heart valve. My own heart sank as I came to grips with the fact that I’d have to leave her behind. I conjured up the image of Greta. You have to leave your comfort zone. I left. It wasn’t easy.

Over ten days, the essential core team came together with Annie’s guidance. She brought in DC Action Lab, which handles logistics for all the big actions in D.C. Samantha “Sam” Miller with that organization has probably trained ten thousand people in civil disobedience and getting arrested.

In turn, Sam brought in our digital team, including Vy Vu, a young Vietnamese artist and student, to do our weekly topic-focused posters. Vy had to design the posters at night, after work, and at breakneck speed. When I first spoke to her by phone, I asked where she came from in Vietnam. “Hanoi,” she replied. “Oh,” I said, “I’ve been there a few times.” And she asked, “Really? How come you went there?” I loved it. There was no reason Vy should know all I had done in the 1970s to oppose the Vietnam War, decades before she was born, or for her to know that because of my trip to Vietnam in 1972, in some political circles they still refer to me as Hanoi Jane.

With just fourteen days to go, my team still didn’t have a name for the action. We had assembled on an emergency basis to come up with one, but after more than an hour of throwing out different ideas, we finally gave up and decided to reconvene the next day. As we were packing up to go home, Greg, the soundman from the documentary film company that had been shooting our work, capturing the process, took off his headphones and said, “What about Fire Drill Fridays?” We all looked at each other and burst out laughing. That was it!

As with all subsequent ones, the first big meeting in D.C. was convened in the Greenpeace office, and about a dozen people were there representing the Sunrise Movement, Friends of the Earth, Climate Action Network, Hip Hop Caucus, Oil Change International, and, of course, Greenpeace. It was critical to get broad movement participation and buy-in. I laid out my vision.