What Can I Do?

In the cell with me were Vasser, Sandra, Medea, and Wendy Fields. I knew that Vasser’s father was nervous about her risking arrest, and I was happy and proud that she felt empowered by her decision to do it. Karen, Annie, Maddy, and the other women were in the next cell over.

While I did wall squats (hey, you gotta seize the opportunity when you can), we talked about climate’s connection to many things, from democracy to war to health, and I got more ideas for upcoming teach-ins.

Turned out that both Medea and Sandra had known my ex the late Tom Hayden. Sandra told me that back in 1965, students at the University of Michigan had been protesting the escalation of America’s involvement in the Vietnam War and of military research being done on campus. Tom, who was the editor of The Michigan Daily at the time, and three thousand other protesters took over Angell Hall, a kind of hallowed place on campus. All night long they held seminars and gave speeches about the history and culture of Vietnam and about Lyndon Johnson’s bombing campaign. And right then and there, it was labeled a teach-in, a new concept. Instead of a walkout or a sit-in, this was a teach-in. Soon the idea of teach-ins spread to other schools.

“In 2015, fifty years after that original teach-in,” Sandra recounted, “Tom and I were invited back to a teach-in on climate change. It was held in the same hall as the original teach-in, Angell Hall. I believe that was Tom’s last big speech before he died.”

This story brought up so many emotions for me. I thought about the fact that next Thursday we would have our first teach-in. I was happy for that link to Tom. I missed Tom and wished he could be with us now to guide and advise us. Strategy was always Tom’s strength. I wondered what he’d think about me being in this jail cell with Sandra and Medea following civil disobedience. I know he would have loved the fact that my step-granddaughter was in there with me. He always favored cross-generational organizing.

To be truthful, though, I had been privately wondering if I could have gotten up the nerve to move to D.C. and launch the Fire Drill Fridays were Tom still alive. I had always been in awe of his fierce intelligence and broad movement-building experience, always feeling myself the student to his teacher. Had he been the least bit skeptical of my idea, which he often was for reasons that sometimes felt arbitrary and personal, I might well have backed off. But then again … maybe not. I was also aware of how much more confident I had grown in the thirty years since Tom and I divorced. Maybe I would have been capable of laughing it off as part of Tom’s quirky ego that could no longer intimidate me.

After three hours or so, people started to be processed out, but I was unable to see who went first. An officer came to talk to Medea about the fact that this was her third arrest of the year and that they were considering keeping her overnight. Instead, they gave her a court date to appear before a judge and let her go, telling her that if she had another arrest before her court date, she would definitely spend a night or two in jail. I was learning the rules that would come in handy in the coming months.

I was one of the last to be released, and as I sat in the cell alone, I had time to reflect on this action that we had hurriedly pulled together based on my sense of urgency the month before. I felt proud that we had done this. I loved the voices we included in this launch: respect for the native land, for youth, and for science. A good beginning but not nearly enough. There was so much more I wanted to learn about all the different topics we planned on covering. Where would we be a month from now? Two months from now? I was ready for that!

About four hours after we were brought into the cell, I was thumb printed, paid my $50 fine, and got my possessions back. Out I went into the glaring sunshine, where I saw the team, plus Debi, my assistant, Annie, Maddy, and Karen, all clapping and cheering and offering chips, tangerines, and water. I was surprised to see that people had waited, but Sam explained that this is what’s called jail support. I hadn’t expected it, all those people there to hug me and thank me for being willing to get arrested for the cause made it different and special. And for every one of our fourteen Fridays that involved arrests, rain or shine or frigid weather, jail support was always there, and in time, when I could no longer risk arrest, I would be part of it myself.

That day cemented for me how important it was to work across movements, to bring together people who work on democracy and women’s issues, indigenous issues, antiracism, peace, labor, and more. It’s not just a matter of good movement manners. We didn’t need to do that; we could have just started this on our own. But taking the time to engage people across movements makes us stronger. There is a saying: “If you want to go fast, go alone; if you want to go far, go together.” The more I was learning about the climate crisis, the more I knew that building a community was how we would grow the army that was needed to change the way this country does business—literally, and for the long haul.

As I thanked everyone for sticking around and started to leave, a Fox TV reporter showed up and stuck a mic in my face while his camera rolled.

“Why have you done this, gone to jail?” he asked with an edge in his voice.

“To get you to cover climate,” I replied, and got into a waiting car.

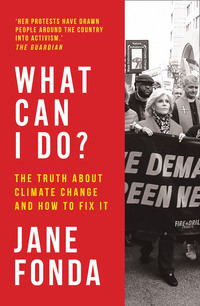

Sam Waterston gets arrested for the first time.

CHAPTER THREE

The Green New Deal

I was bleary-eyed the morning after our launch, but when I looked at my iPhone, I realized Fire Drill Friday had gone viral. Ira reported later that there were 8,670 press articles online, on TV, and in print with amazing images of the entire thing, especially my arrest in my red coat. People had been calling and texting me from all over to congratulate me and thank me for standing up for the planet. I thought, Oh my God, what’s happening?

I did twelve more interviews that week, and we had another four-thousand-plus stories in the media … all around the world. And while all this was going on, I had to study up on the Green New Deal, the focus of the next week’s first teach-in on Thursday and Fire Drill Friday, when I’d be joined by my friend the actor Sam Waterston and two high-profile experts on the Green New Deal. At my age, the whole livestreaming thing was foreign, and I was nervous.

Wednesday morning, one of the experts let me know that his young daughter was ill and he wouldn’t be able to come, and Wednesday afternoon the other one told Greenpeace that she was too ill to attend. Clearly Sam and I couldn’t hold a teach-in on the Green New Deal by ourselves. I went into meditation mode to quiet my growing panic. Was it always going to be this dicey?

Fortunately, Greenpeace got a Thursday morning commitment from a young activist, Joanna Zhu, a fellow within the Sunrise Movement’s political department who, though not a full-on Green New Deal expert, knew enough to explain it to our teach-in audience.

The Teach-In

I arrived at the Greenpeace conference room, which we were using as the digital teach-in set, early Thursday evening. Firas had suggested that the teach-ins have a homey vibe, so I had rented furniture online and created a comfortable sitting area with couch, chairs, and coffee table in a corner of the conference room. I made sure Naomi’s book was prominently displayed on the coffee table, pilfered some plants from staff desks to dress up the side tables, and arranged the Fire Drill Friday and Green New Deal posters appropriately. It was the first time I’d seen everything all put together, and I must say the effect worked pretty well. The documentary crew was there to film, and Carla, with the digital team, set up an iPhone on a tripod to livestream the whole thing.

Because there was no teleprompter, I had note cards for the opening and closing, as I would for every subsequent teach-in, with questions for the guests and additional points I wanted to make if there was time.

At 7:00 p.m. sharp, Carla counted down, 3, 2, 1, and off we went.

“The Green New Deal is not a policy or even a bundle of policies,” I said. Talking to the tiny camera on a tripod about six feet away felt funny. It was hard to believe that that little camera could potentially be the eyes and ears of tens of thousands of interested people from around the world, which, as it turned out, it would become.

I was so jacked up that I introduced Sam Waterston as Sol Bergstein, which is the name of his character in Grace and Frankie, and was momentarily confused when Sam kept saying, “No, Jane. I’m not Sol Bergstein.”

“The Green New Deal is a framework,” I said, “an integrated, systemic response to the multiple crises of climate, of democracy, and of equality.”

When I had finished my opening, I asked Joanna to explain the Green New Deal to us. She spoke for a minute instead of five and then turned to me. My heart sank. OMG, that’s it? I was going to have to wing it.

The three of us did a pretty decent job describing what the Green New Deal is, but let me just summarize it here so we’re all on the same page.

THE GREEN NEW DEAL

The Green New Deal details the steps our country needs to take to prevent the most severe impacts of a changing climate. Introduced by Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Senator Ed Markey in February 2019, the Green New Deal warns that for us to survive and to avoid huge climate catastrophes, we must prevent global temperatures from rising 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) above preindustrial levels. This requires a 40 to 60 percent reduction in global carbon emissions by 2030—in a decade—and then further reduction to net zero by 2050.

As the country that has produced 20 percent of these emissions through 2014, the United States must lead on this issue. We have the capital and the technology to show the world how to transform our way of life to one that is healthy and sustainable for all. The Green New Deal describes a ten-year mobilization to save the planet, where the government funds thousands of good-paying jobs that will bring clean water and clean air and access to nature and to healthy food for all of our citizens while establishing renewable, zero-emission energy sources to power our economy.

This is why having “New Deal” in the title makes sense. To tackle such large issues that affect so many people, the effort is similar to the New Deal and World War II, dire times when the federal government rose to the challenge. We need just that kind of effort to head off climate catastrophe. And the Green New Deal shows us the way.

Much like the New Deal, the Green New Deal begins with jobs, good ones: retrofitting and upgrading buildings for maximum energy efficiency; updating water quality and conservation; remediating toxic waste dumps; and generally increasing efficiency, safety, affordability, comfort, and durability. As with the jobs created under the New Deal in the 1930s, people would be trained in skills that would be in demand in the new economy created by the transition off fossil fuels. The work to be done is local, and the local communities will be the ones that benefit from these changes. While polluting industries are phased out, other sustainable industries will replace them, spurring economic development.

The changes wouldn’t just come in the cities either. The Green New Deal would also work with farmers and ranchers to remove pollution and greenhouse gas emissions from the agricultural sector by investing in electric cars and trucks, farm machinery, buses, and high-speed rail. The GND supports family farming, invests in sustainable land use practices, and restores the natural ecosystems through proven low-tech solutions that increase soil carbon storage and clean up hazardous waste sites.

The genius of the Green New Deal is its inclusiveness. It doesn’t just focus on greenhouse gas emissions. Vulnerable communities including indigenous peoples, communities of color, poor and low-income workers, and people who live in rural communities are the primary victims of pollution and extraction of natural resources; under the Green New Deal they would be the beneficiaries. The GND jobs program would focus on opportunities for workers affected by the transition off fossil fuels and training and advancing the right of all workers to organize, unionize, and collectively bargain would be guaranteed, and the overseas transfer of jobs and pollution would be stopped.

Truthfully, I was originally upset that the resolution seemed to go far beyond climate. But the more I learned, the more I realized it couldn’t be any other way. We can’t just move to green energy and leave it at that. The transition to a fossil-free world must be framed in such a way that people and communities that have been most directly harmed by the old energy system can be made whole and given agency over their energy delivery systems. Had there been a Green New Deal in place in early January 2020, COVID-19 would have been much easier to contain and our health-care system much more resilient.

With Fire Drill Fridays, I wanted people to see the climate crisis as a chance to create a world of new possibilities for fairness, prosperity, and good health. If enough people demand it, just as they did with the original New Deal, we can make it happen. This will mean the climate movement has to stretch in a few ways.

First, the conventional nature/wildlife conservation people need to widen their perspective on “environment.” Environments where fossil fuels—coal, oil, and gas—are drilled and processed may be industrialized and polluted, but they are environments nonetheless. Many people in the United States never see these communities on the front line of the fossil fuel economy. Too often they are out of sight and out of mind. Through the Fire Drill Fridays platform we were creating, I wanted to use my celebrity to make the real impacts of fossil fuels visible to everyone. To pass a Green New Deal, the environmental movement must unite and grow to include people who hadn’t considered their environment something they had the power to change.

Second, the climate movement needs to approach fossil fuels from two sides: using less and making less. See, when it comes to efforts to reduce fossil fuel emissions—which are the primary driver of the climate crisis—environmentalists and elected leaders have historically focused on the demand side, meaning they support approaches to reduce the demand for fossil fuels with new green sustainable energy, electric vehicles, and energy conservation. Those are all great, and we need them all, but to add up to enough emissions reductions to keep below that crucial goal of 1.5 degrees Celsius, we also need to reduce the supply of fossil fuels being extracted, pumped, and fracked. Without a reduction in fossil fuels at both ends, it is easy for people to look around at the growing number of solar panels and electric vehicles and think the problem is being solved while being unaware of what’s happening to people different from them in environments they may never be exposed to. To pass a Green New Deal, the traditional environmental movement must grow to include issues beyond conventional conservation and wildlife concerns and include people who might be very different from themselves. That’s how we will build a movement big enough to win and ensure we leave no one behind.

Critics say shifting away from fossil fuels will wreck the economy, but many experts see enormous potential to create jobs and stimulate the economy through a Green New Deal. The Stanford University professor Mark Jacobson, in his study published in the journal One Earth, described how going 100 percent green could pay for itself in seven years. Revamping power grids and remaking transportation, manufacturing, and other systems to run on wind, solar, and hydro power would cost $73 trillion. But, Jacobson says, that would be offset by annual savings of almost $11 trillion. Jacobson claims in his paper that studies among at least eleven independent research groups have found that transitioning to 100 percent renewable energy in one or all energy sectors, while keeping the electricity and/or heat grids stable at a reasonable cost, is possible.

During our livestream, I asked Joanna what she would say to the critics who call the Green New Deal a “wish list for the far left”? I liked her response: “It isn’t just a wish list; it’s a to-do list. It’s our statement of intent.”

Cities around the United States are already moving to implement certain aspects of a Green New Deal, eliminating fossil fuels from their electricity systems, moving to electrify mass transit vehicles, and requiring new homes to have electric heat pumps. These are great signs of progress, but without the power and resources of the federal government we can’t scale it up fast enough. Hence, it’s too late for moderation.

I said, “Forty years ago, Shell and Exxon’s own scientists warned them that what they were spewing into the atmosphere had the potential to cause irreversible damage. Had they not lied and hid that from the public, we could have had a moderate, incremental transition to renewable energy.”

“Yes, and I am a moderate and I am here and that’s the reason,” Sam said. “Because the time to do this in a gradual and moderate way is past, so a moderate person wants to hurry up because that’s the only available choice now.”

Sam turned and looked directly into the camera. “So, whatever your temperament is, whatever your inclination is, this is the definition of moderation now, taking these different kinds of very bold steps. What looks like radical today is actually moderation, given the size of the problem itself and the time we have left in which to slow it down.”

Sam Waterston speaks.

Sam added, “The insidious thing about this is that the catastrophe is being experienced differently in different places and that makes it possible for a privileged person like me to deny that it’s happening. ‘I’m okay. There’s a little trouble over there maybe, but we’re all right.’ But what we need to do is exercise our empathy and our imaginations. We have to be able to see ourselves in the typhoon victims in Japan and people that are being driven out of their homes because of climate change in Latin America. We have to see that their problem is our problem. This isn’t just altruism. It’s enlightened self-interest.”

“Right,” I said. “And because of the heat already baked in, it’s going to get worse before it begins to slow down. Hence, one of the things that the Green New Deal talks about is doing everything we can to prepare for the really challenging emergencies that are going to happen no matter what we do. And a country whose people feel safe and respected, people who are paid a decent wage, communities that know they are not considered sacrifice zones, are going to be much more able to withstand what’s going to come at them in terms of extreme weather. The Green New Deal will grow resilience in people and in communities.” Five months later, the coronavirus provided a tragic lesson on the importance of being prepared.

I was exhausted by the effort it took to make our first teach-in work in spite of the challenge of having two of us non-experts in the Green New Deal. I fled home to my hotel room and fell into a deep sleep.

The Rally

The next morning was the second Fire Drill Friday, and it was a very different scene from the prior week. The rally area was overflowing with press, paparazzi, and more people.

Onstage I opened with a brief history of the 1930s New Deal, because I wanted to remind people of this country’s ability to rise to the occasion when faced with a monumental crisis.

“Make no mistake, change is coming, by disaster or by design,” I said. “The Green New Deal provides the design to bring us all into a sustainable future.”

Most of our speakers that day were young, and it wasn’t until I heard them that I realized the extent to which many are traumatized by the prospect that the future they will inherit may well border on unlivable and are resentful that they must sacrifice their time, their educations, their chosen professions even, to fight for a future. I was reminded how the Green New Deal gives these young people, specifically, a vision of that future worth fighting for.

The first person to speak, Abigail Leedy, was an eighteen-year-old organizer with the Sunrise Movement. She told the crowd that a month earlier she found out she’d been accepted to college on a day when she was part of a sit-in at a congressman’s office to demand that he support the Green New Deal. When she thought about what was happening to the climate, how the world was on fire, she decided she had to forgo college to fight full-time for a Green New Deal.

She spoke from personal experience about how, in her hometown of Philadelphia, summers now are the hottest on record, and the school district canceled classes for six days in her senior year because the temperatures were so high it feared it was not safe for the students to be inside the un-air-conditioned classrooms.

WE’VE DONE IT BEFORE: THE NEW DEAL

The monumental circumstances that created the original New Deal came about at a time of tremendous social unrest when the Great Depression threw a quarter of the population out of work. It was a time of labor protests, social protests, and riots about economic insecurity and inequality. People demanded that the government step in to alleviate these hardships.

The Depression was also a time of environmental collapse and mass migration. Fossil fuel companies encouraged midwestern farmers to shift to mechanized plowing, which disrupted native grasses that held the topsoil in place. When drought hit the region in the 1930s, high wind and choking dust killed livestock, and crops failed on the overplowed land, forcing 2.5 million people to flee. My father, Henry Fonda, starred in the movie The Grapes of Wrath about that crisis.

Angry, organized citizens, workers, and farmers made their demands known to Roosevelt, and what he said to them is important for us to keep in mind today. He said, “I agree with you. Now go out and make me do it.” Pressure from citizens made him do it, and in order to lift the country out of its deep suffering, the president launched the New Deal.

In his first hundred days after he was sworn in as president, Roosevelt created government programs that put many millions of people to work in hundreds of public projects all across the country.

The Civilian Conservation Corps employed three million young men to restore the Great Plains; the Works Progress Administration hired millions to construct public buildings and roads like the dams and waterworks that brought power to the South through the Tennessee Valley Authority. This massive outlay of money for the public good built America’s middle class.

It wasn’t perfect. In order to get southern Democrats to support it, Roosevelt cut African Americans out of much of the New Deal, and women were largely ignored. We must learn from those mistakes and do better going forward. But the New Deal got so much right, and we benefit from that today.

The rich and powerful hated the New Deal because it set a precedent for the federal government to play a central role in the economic and social affairs of the nation. It was criticized as fascist or socialist; bankers tried to overthrow Roosevelt. Big Business, Big Railroads, Big Banks ranted and raved against it, but there were millions in the streets demanding that Roosevelt do even more because it was helping them, and because of that it succeeded.