What Can I Do?

We spent a long time discussing who we were targeting with these actions. Climate deniers? Conservatives? Independents? Activists? And we decided we needed to aim for people who acknowledge there’s a man-made crisis; who support the climate movement and are thinking about maybe doing more but don’t know what that could be; who are confused, paralyzed, or tilting toward hedonism or fatalism. Hedonism being the thinking that because everything’s going to hell anyway, I might as well eat, drink, and tune out with shopping or debauchery. Fatalism being the thinking that I had started to tilt toward prior to Labor Day: Humans have done so much harm we don’t deserve to survive.

The bulk of the meeting was spent defining our demands and calls to action. We whittled it down to the three essential demands without which we will never meet the Paris Agreement on climate goals in a sustainable, fair way.

SUPPORT THE GREEN NEW DEAL

NO NEW FOSSIL FUEL EXTRACTION

PHASE OUT EXISTING FOSSIL FUELS WITH A JUST TRANSITION TO CLEAN RENEWABLE ENERGY

We decided our calls to action would be the following:

VOTE:

Vote for the climate in every election up and down the ballot. Vote for candidates who are in favor of a Green New Deal and a bold and responsible transition from fossil fuels to clean renewables.

VOICE:

Make your voice heard. Initiate conversations about climate with your family and colleagues. Tell your candidates or elected officials that climate can’t wait. Call them, sign petitions, and go to their town halls. Write letters to the editor of your local paper. Divest from fossil fuel companies and invest in a sustainable future.

USE YOUR FEET—WITH OTHERS!

Join an organization working for real climate solutions. We are stronger together than we are alone! Join marches, do outreach, recruit friends to join. Show up for the communities on the front lines of the fossil fuel economy. Show up for ALL OF US. Listen to communities most impacted by climate change, and if you can, put your body on the line wherever people are fighting on the front lines. Start by joining a student climate strike or Fire Drill Friday action in your own community!

After reading Naomi’s book, I recognized that there was so much more that I wanted to know and wanted to bring to a bigger audience. People needed to know what was really happening! I suggested weekly teach-ins before each rally, each one focusing on a different aspect of the climate crisis and featuring experts, scientists, and activists. Karen Nussbaum said rallies weren’t ideal places for teach-ins but we could hold them the evening before, maybe in a theater in D.C., and film them.

Karen is a labor movement activist who has been my friend since the early 1970s, when she was an organizer with Tom and me in the Indochina Peace Campaign. She is the founder of Working America, the community-outreach arm of the AFL-CIO, on whose board I sit, and in the 1980s she founded 9to5: National Association of Working Women. It was she who inspired me to make the film 9 to 5. Karen was here to help us find ways to bring more of the labor movement into collaboration with the climate movement; in addition, her husband, Ira Arlook, had agreed to serve as the press coordinator for our weekly actions.

That was when Carla Aronsohn on our digital team asked, “Well, why not do the teach-ins digitally. We’re setting up your website, and we can do them livestreamed and archive them on your site.” And that is how our Thursday evening teach-ins came to be.

In the days following, I had an important meeting with eight of the leading D.C. student climate strikers, ranging from fourteen to twenty-three years old, from the Sunrise Movement, U.S. Climate Strikes, Zero Hour, and Fridays for Future. Yes, the youth in these organizations had called upon adults to step up and join the fight for their future, but an aging movie star bopping in from Hollywood whose action would likely get a lot of attention on their Friday? I needed and wanted their blessings.

It was a real learning experience. I was amazed at the students’ depth of passion, organizing smarts, and sensitivity to the need to center vulnerable communities and indigenous peoples. Even the youngest wasn’t afraid to correct me if she felt I was on the wrong path. It soon became clear that they welcomed this addition to their school strikes, but there were many things we had to iron out with them before my first action, which was only ten days away. Would students stand with me for that action? Who should it be? Sebastian Medina-Tayac and his seventeen-year-old sister, Jansikwe, are members of the Piscataway Indian Nation on whose land we would hold our actions at the Capitol. It was decided Jansi would open by welcoming us to her people’s land. Jerome Foster II, a seventeen-year-old African American student and founder and director of OneMillionOfUs, which is mobilizing a new generation of young people to register to vote, has been climate striking every Friday for a year in front of the White House. He would march from the White House to join us at 11:00 a.m. and speak.

Things were coming together. It was no longer one person’s idea. It was taking shape and evolving into a team effort, and other organizations were feeling included and heard. In fact, it felt meant to be.

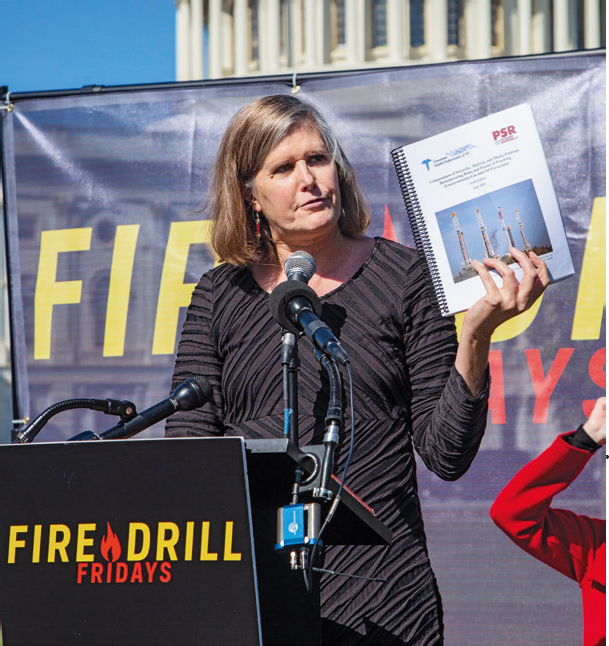

Jane speaks at the first Fire Drill Friday, holding up a copy of Naomi Klein’s book On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New Deal.

CHAPTER TWO

The Launch

It was a beautiful day. On the morning of October 11, 2019, we all gathered in the United Methodist building near the Capitol for a pre-rally briefing. I wore the red coat I had bought on sale a few days before at Neiman’s and a black-and-white-checked cap to hide the two inches of gray hair I was letting grow in. Hair epiphanies have always accompanied my life transformations, and going gray felt right for my new (and maybe final) turning point. Little did I know that the red coat would become a popular Halloween costume a few weeks later and a pop culture totem.

I was scared and I hadn’t slept. It’s that fear: What if I give a party and no one comes? We thought it would work, but none of us were certain if this weekly action would actually gain traction and make a difference.

The core team was all there plus two of the speakers and about a dozen activists who wanted to engage in civil disobedience with me and risk arrest, like Karen Nussbaum, Annie Leonard, and Steve Kretzmann, director of Oil Change International. My step-granddaughter, Vasser Turner Seydel, showed up in a bright red sweater. I had filmed her birth and now here she was, twenty-four years old and ready to risk arrest with Grandma Jane. I was moved and impressed.

I greeted people as they came into the somewhat cramped room filled with a long, oak refectory table running down the middle and sturdy chairs that reminded me of the furniture at Emma Willard, my old boarding school.

Jane stands with Naomi Klein, at the morning briefing ahead of the launch of Fire Drill Friday on October 11.

At 9:30, Sam, our head of logistics, quieted us all down and began the briefing that she would do for every subsequent Fire Drill, explaining where we would go when we left the building, who would speak when, where we’d commit the civil disobedience, and what to expect if we were arrested. At her direction, everyone planning to risk arrest took off their jewelry and made sure we had $50 and an up-to-date photo ID on us. If they didn’t have the $50, we gave it to them. I saw Dr. Sandra Steingraber, a distinguished scholar in residence at Ithaca College and a biologist who would be speaking at the rally, taking off her necklace. Ah, no ordinary scholar, she’s risking arrest! How cool!

Then Firas Nasr, from our digital team, told us that because we’d be putting our bodies on the line, we’d best get into our bodies, and he took us through a brief meditation, bringing us inward, which I needed to calm my nerves. That was followed by three from-the-gut martial arts shouts to ground us. It worked.

Flanked by the speakers and friends holding the Fire Drill Friday signs with our three demands, I stepped out into the warm, welcoming day. I felt tears running down my cheeks. Here we go.

We were met by a phalanx of television cameras and photographers, walking backward as they filmed us marching and chanting. There were more of them than there were of us. The interviews Ira had arranged for me to do with big media outlets had clearly generated attention.

As we crossed the intersection between the Supreme Court and the Capitol, their majestic columns and curves spoke to me of history and of moral authority. Would that the goings-on inside right then matched these imposing facades. The impressive buildings added to the feeling that our little group was ragtag and inconsequential. Our chants lacked confidence, and there weren’t enough of us to make a lot of noise anyway. At the stage where our banner was erected, I could see our supporters. Sparse. Fifty at most. Well, it was a start, and hopefully the media coverage and our livestream of the rally would expand our reach.

I welcomed people and thanked them for coming. “I’d like all of you to think about this,” I said. Good. My voice felt strong. “The same toxic ideology that took this land from people who already lived here, that kidnapped people from Africa, turning them into slaves to work that stolen land, and justified it by saying that those kidnapped and displaced people were not human beings, cut down the forests, and exhausted the natural world just as it did the people. This foundational, extractive ideology of commodification is the same one that has brought us the human-driven climate change that we’re facing today.” And with that, I invited Jansikwe Medina-Tayac to come up and welcome us to her people’s land.

The size of the crowd at the launch.

Jansikwe Medina-Tayac kicks things off at the first Fire Drill Friday.

Jansi, with her long curly hair and blue jeans, stepped from behind the banner to the mic. I was glad that we had already spent time together. Without the young climate activists who had been striking every Friday supporting us, these actions would not have worked out. Giving them this platform was proof of our unity.

“Hello, everyone, my name is Jansikwe. I am seventeen years old, and I am a member of the Piscataway Indian Nation.” Her voice was strong and confident. “Our traditional territory spans all the way from the Potomac River down to the Chesapeake Bay. I’m here not only to welcome you to this space, but to remind you that indigenous people have been fighting for this earth since the early 1600s. We are the original protectors of this earth and its indigenous ways of life.”

As I listened to this young indigenous woman, I marveled at how remarkable it is that despite all that European colonizers have done to the original inhabitants of this land, many are still willing to offer welcome, advice, and guidance about how we must live in relationship with nature and each other. In the course of the fourteen Fire Drill Fridays, I would learn so much more about the critical role indigenous peoples play in fighting climate change and how disproportionately impacted they are by fossil fuel extraction.

“We need to recognize and change the system that encourages us to take and take and never give back,” said Jansikwe. “Native kids in places like Standing Rock should not have to take time off from school to fight for their lives. We need every person, every helping hand, every heart in the world, to come together and help end this attack on our planet.” She stepped off the platform to rejoin her mother and brother.

Because this was the launch, I wanted to take this opportunity to explain why I had moved to D.C. to hold these actions.

“So much is happening in the news. There’s so much noise, right? We have to ensure that the climate crisis remains front and center, and that’s why we’re here.” I spoke about how Naomi Klein’s book, Greta Thunberg, and the student climate strikers had inspired me to get out of my comfort zone. “So the question for the rest of us is, what are we willing to give up? What time and energy will we devote to it? What sacrifices will we make?

“I’m standing with the young people. I want to help lift their message. Greta Thunberg said we have to behave like we’re in a crisis. Our house is on fire. And so we’re calling these rallies Fire Drill Fridays.

“Every Friday for the next four months at 11:00 a.m., we’re going to be right here. And every Friday, we’re going to focus on a different aspect of the climate crisis.”

I listed our demands: Pass a Green New Deal, stop fossil fuel expansion immediately, phase out fossil fuels as soon as possible but definitely within thirty years, secure a fair deal for workers and communities most impacted by this transition. Our other mission was education. Each Friday we would invite scientists, experts, and people from frontline communities along with celebrities to focus on a different aspect of the climate crisis. “We need to understand that at least 97 percent of the world’s climate scientists agree that we are facing a drastic emergency, that it is man-made, that we have a little over a decade before the tipping point is reached. Ten years to reduce fossil fuel emissions roughly in half and then reduce to net zero by 2050. There aren’t two sides to this story.”

When I was done, I brought up seventeen-year-old Jerome Foster, who startled me with his command of the stage. Clearly, he was accustomed to speaking at rallies. I had spoken at many myself over my years of activism, but not on a regular basis, and of late my throat had had a tendency to close up at rallies, making it difficult for me to project. I knew I had to be careful, warm up my voice, and not overdo the chants.

Jerome focused on the need for unity. “Change can only happen with unity. Change can only happen when everyone is at the table, because only in the cracks of division can corruption seep in, and only in the cracks of division can pollution seep in. We are a part of one earth, one pale-blue dot that’s in the middle of an endless sea of blackness. What we’re saying is that we must act as such, we must act as if we are one people, one planet, and one globally interconnected nation.” Then he exhorted people to vote and to write to their elected officials, and he led us in a chant:

Jerome Foster at the first Fire Drill Friday.

Take it to the polls!

Take it to the streets!

Take it to the polls!

Take it to the streets!

Next, Sandra Steingraber, the biologist and scholar, took the mic. She described how fracking “swung a wrecking ball at our climate system” and how it exhumed the life buried deep in the earth thousands of years ago to quell our unquenchable thirst for oil.

“Diatoms and sea lilies and squid. We blow up a cemetery of prehistoric sea creatures that we rename fossil fuels in order to light their bodies on fire in the crematoria we call power plants and internal combustion engines,” Professor Steingraber said.

A brilliant mind, Professor Steingraber illuminated connections to bring a fresh focus on the destruction inherent in the way we live. It was hard to hear her list all that we had lost and what we’d be losing in the near future. Fracking destroys our drinking water and discharges dozens of carcinogens into our atmosphere. The carbon released by the oil it collects destabilizes our oceans, our food supply, and our water supply, sending millions of climate migrants in search of safety.

“We are losing the world’s fish stocks and coral reefs,” she said. “We are losing insects, pollinators, and reliable rainfall. Failed harvests are driving migration crises across the globe. Does that sound like a smart energy system to you? No, it’s primitive and crude. Crude as in crude oil.”

The other crude effect of fracking goes mostly unnoticed, she pointed out. Energy companies sell off the by-products of fracking to chemical companies to make the single-use plastics that are choking our ocean life and often end up burned in incinerators—adding to climate change and pollution.

The passion I heard in her voice came from personal experience. Forty years ago, when she was just twenty, she was diagnosed with a rare cancer that her doctor said was likely caused by environmental carcinogens. Immediately she decided to become a public health research scientist instead of a doctor, but at that moment she wasn’t sure she’d live long enough to realize any of her dreams.

“Like any teenager, I had felt immortal. After the diagnosis, the future was uncertain and, if it existed at all, was full of dread and suffering,” she said. “So my message to youth today is, I get it. When you say that your future has been stolen and held hostage by the actions of others, I understand. When you see grown-ups all around you carrying on as if everything is still fine and there is no catastrophe, I know that unbearable feeling, too. We’ve all become cancer patients now.”

Dr. Steingraber’s speech was a revelation: The bodies of marine animals that died 400 million years ago are being weaponized to destroy the bodies of sea creatures living in our oceans now.

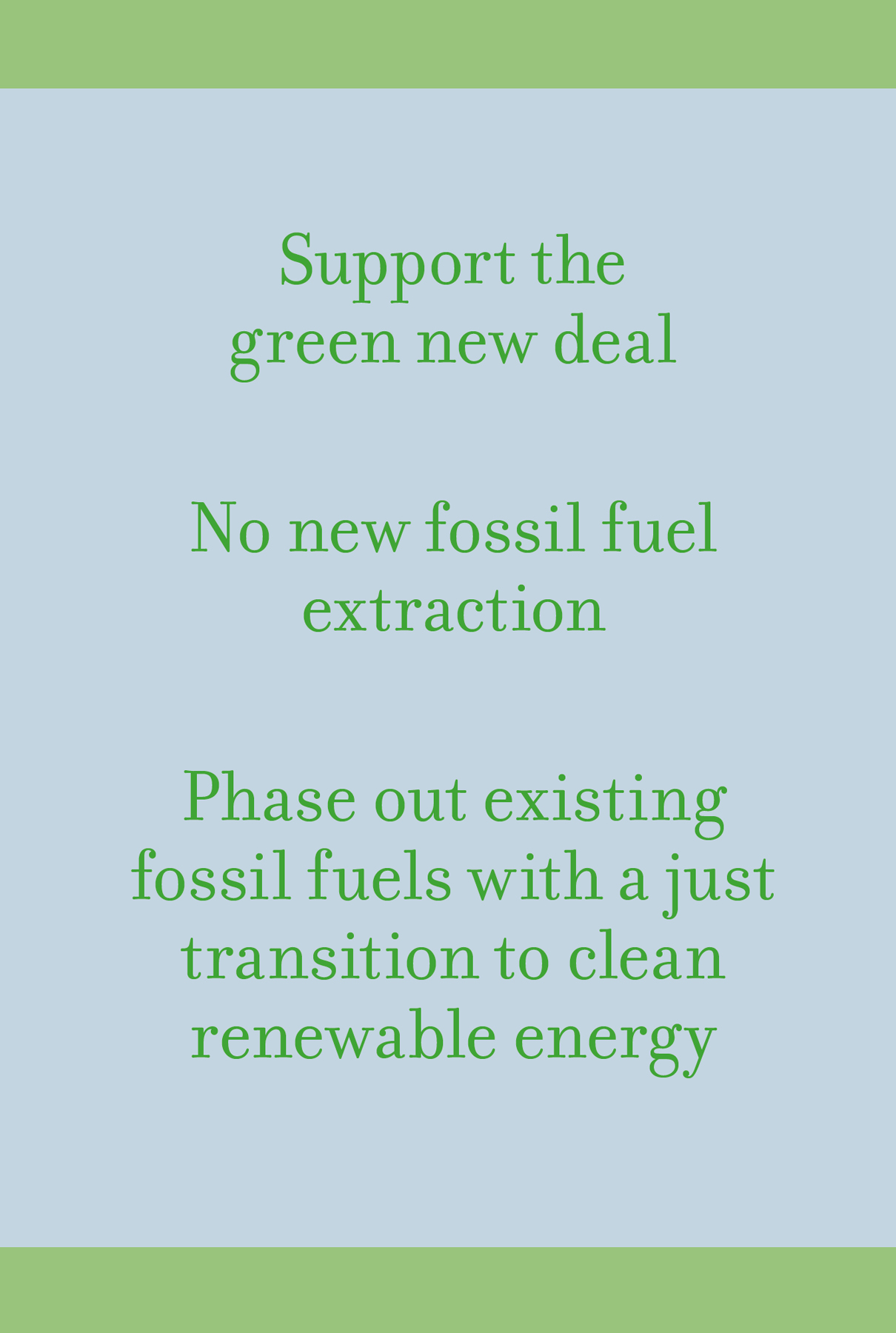

Sandra Steingraber speaks.

I hadn’t made that connection. Nor the fact that making plastics was a way for oil companies to use the chemical industry to deal with their waste disposal, thereby creating the horrendous waste problem the rest of the world is trying to solve. What an interesting woman, Sandra Steingraber. A biologist, an activist with the creative instincts of a poet who, despite the dangers she described, left us with a message of hope, the same one her adoptive mom had given her when she started her battle with cancer: “Don’t let them bury you until you’re dead.”

“Friends, I am here today with science in my hands, with love in my heart for the whole sunlit planet and all of those who walk its surface, and with a cancer survivor’s fierce determination to fight for life, no matter what the odds,” she said. “The fossil fuel industry will not bury us. We will live to bury them.”

I found her speech so profound, so striking. The imagery she used to stir the crowd to action stayed with me a long time after she finished. As soon as she left the podium, I asked her for a copy of her remarkable speech, because I knew I’d read it again.

When the rally was over at noon, we marched behind the big “Fire Drill Friday” banner, chanting,

Tell me what democracy looks like!

This is what democracy looks like!

The seas are rising and so are we!

The group risks arrest at the launch.

We marched past a line of police cars toward the Capitol steps, the press in front of us walking backward, occasionally tripping and running into things. The line of about ten police officers standing on the steps began to move to the side to make room for us. They were well practiced. There were around sixteen of us who mounted the steps and turned around to face the small crowd and media people, which was being pushed back by another line of police. “Move back, people. Move all the way back.”

And soon there was a wide distance between those of us risking arrest and the others, though we all kept chanting. My step-granddaughter, Vasser, was right next to me along with Carroll Muffett, director of the Center for International Environmental Law; Steve Kretzmann, director of Oil Change International; Wendy Fields, director of Democracy Initiative; Medea Benjamin with CODEPINK; the twenty-four-year-old climate activist Sebastian Medina-Tayac; Annie Leonard, director of Greenpeace USA; the Greenpeace staffer Madeline Carretero; and Sandra, the poetic biologist.

The head police officer gave us the first warning that we must leave or risk arrest. We kept chanting. Then a second warning. A few people left, but we kept chanting. The final warning, and that was it. One at a time, officers secured our hands behind our backs with white plastic zip ties. They hurt.

Annie Leonard and Maddy Carretero get arrested on the Capitol steps.

I wasn’t scared. I had been arrested before, but this was my first arrest for civil disobedience. In 1970, I had been arrested in the Cleveland airport returning from Canada, where I had just begun a national speaking tour about the atrocities of the Vietnam War.

Back then, the arresting officer told me the Nixon White House had ordered my arrest. The police took my notebooks and my address book and dozens of little plastic bags containing the vitamins I took with each meal. The charge was drug smuggling. I was put in a cell with a woman in the throes of drug withdrawal. I didn’t know what was going to happen to me.

This time was different. I stood chanting on the steps of the Capitol, energized. I was doing what I had wanted: putting my body on the line and aligning myself fully, body and spirit, with my values. I felt empowered. The people around me seemed to feel the same. As each of us was taken by an officer to the waiting vans, people cheered, clapped, and chanted in support. It felt good.

Jane Fonda gets arrested. Behind her stand Annie Leonard and Maddy Carretero.

When I arrived, several women were already sitting in a row on one side in the back of the van, which was divided in two. Even though I’m strong, it was a high step up with nothing to hold on to and my hands cuffed behind my back. The officer helped by boosting me up by my behind, and I flashed onto a scene in the sixth season of Grace and Frankie when Peter Gallagher had to help me into an SUV the same way because Grace is too old to do it on her own. Oh, well, Fonda. This is your new reality.

It took an inordinate amount of time before we finally arrived at the police station, where we were off-loaded and taken inside. There, we were searched, and everything we weren’t wearing, including glasses that weren’t prescription, identification, and money, was put in a clear plastic bag and marked with our name. Given what we were committing civil disobedience for, the extensive use of plastic was glaring. My red coat was so new I hadn’t yet realized it had real pockets that had to be unstitched open. Hence, my money and driver’s license were in my bra, which the officers seemed to find amusing. They had to release me from the cuffs so I could get them.

The thin white plastic handcuffs were cut off, tossed, and replaced by thicker black ones that screwed into place and were apparently recycled after use. Then we were led into another room containing two cells, each painted hospital green, each with a sleek metal slab of a bed/bench and an all-metal toilet. There was nothing that could be removed or broken off. No sharp corners.