The Stones of Venice, Volume 2 (of 3)

§ XV. But the severity which is so marked in the pulpit at Torcello is still more striking in the raised seats and episcopal throne which occupy the curve of the apse. The arrangement at first somewhat recalls to the mind that of the Roman amphitheatres; the flight of steps which lead up to the central throne divides the curve of the continuous steps or seats (it appears in the first three ranges questionable which were intended, for they seem too high for the one, and too low and close for the other), exactly as in an amphitheatre the stairs for access intersect the sweeping ranges of seats. But in the very rudeness of this arrangement, and especially in the want of all appliances of comfort (for the whole is of marble, and the arms of the central throne are not for convenience, but for distinction, and to separate it more conspicuously from the undivided seats), there is a dignity which no furniture of stalls nor carving of canopies ever could attain, and well worth the contemplation of the Protestant, both as sternly significative of an episcopal authority which in the early days of the Church was never disputed, and as dependent for all its impressiveness on the utter absence of any expression either of pride or self-indulgence.

§ XVI. But there is one more circumstance which we ought to remember as giving peculiar significance to the position which the episcopal throne occupies in this island church, namely, that in the minds of all early Christians the Church itself was most frequently symbolized under the image of a ship, of which the bishop was the pilot. Consider the force which this symbol would assume in the imaginations of men to whom the spiritual Church had become an ark of refuge in the midst of a destruction hardly less terrible than that from which the eight souls were saved of old, a destruction in which the wrath of man had become as broad as the earth and as merciless as the sea, and who saw the actual and literal edifice of the Church raised up, itself like an ark in the midst of the waters. No marvel if with the surf of the Adriatic rolling between them and the shores of their birth, from which they were separated for ever, they should have looked upon each other as the disciples did when the storm came down on the Tiberias Lake, and have yielded ready and loving obedience to those who ruled them in His name, who had there rebuked the winds and commanded stillness to the sea. And if the stranger would yet learn in what spirit it was that the dominion of Venice was begun, and in what strength she went forth conquering and to conquer, let him not seek to estimate the wealth of her arsenals or number of her armies, nor look upon the pageantry of her palaces, nor enter into the secrets of her councils; but let him ascend the highest tier of the stern ledges that sweep round the altar of Torcello, and then, looking as the pilot did of old along the marble ribs of the goodly temple ship, let him repeople its veined deck with the shadows of its dead mariners, and strive to feel in himself the strength of heart that was kindled within them, when first, after the pillars of it had settled in the sand, and the roof of it had been closed against the angry sky that was still reddened by the fires of their homesteads,—first, within the shelter of its knitted walls, amidst the murmur of the waste of waves and the beating of the wings of the sea-birds round the rock that was strange to them,—rose that ancient hymn, in the power of their gathered voices:

The sea is His, and He made it:And His hands prepared the dry land.CHAPTER III.

MURANO

§ I. The decay of the city of Venice is, in many respects, like that of an outwearied and aged human frame; the cause of its decrepitude is indeed at the heart, but the outward appearances of it are first at the extremities. In the centre of the city there are still places where some evidence of vitality remains, and where, with kind closing of the eyes to signs, too manifest even there, of distress and declining fortune, the stranger may succeed in imagining, for a little while, what must have been the aspect of Venice in her prime. But this lingering pulsation has not force enough any more to penetrate into the suburbs and outskirts of the city; the frost of death has there seized upon it irrevocably, and the grasp of mortal disease is marked daily by the increasing breadth of its belt of ruin. Nowhere is this seen more grievously than along the great north-eastern boundary, once occupied by the smaller palaces of the Venetians, built for pleasure or repose; the nobler piles along the grand canal being reserved for the pomp and business of daily life. To such smaller palaces some garden ground was commonly attached, opening to the water-side; and, in front of these villas and gardens, the lagoon was wont to be covered in the evening by gondolas: the space of it between this part of the city and the island group of Murano being to Venice, in her time of power, what its parks are to London; only gondolas were used instead of carriages, and the crowd of the population did not come out till towards sunset, and prolonged their pleasures far into the night, company answering to company with alternate singing.

§ II. If, knowing this custom of the Venetians, and with a vision in his mind of summer palaces lining the shore, and myrtle gardens sloping to the sea, the traveller now seeks this suburb of Venice, he will be strangely and sadly surprised to find a new but perfectly desolate quay, about a mile in length, extending from the arsenal to the Sacca della Misericordia, in front of a line of miserable houses built in the course of the last sixty or eighty years, yet already tottering to their ruin; and not less to find that the principal object in the view which these houses (built partly in front and partly on the ruins of the ancient palaces) now command is a dead brick wall, about a quarter of a mile across the water, interrupted only by a kind of white lodge, the cheerfulness of which prospect is not enhanced by his finding that this wall encloses the principal public cemetery of Venice. He may, perhaps, marvel for a few moments at the singular taste of the old Venetians in taking their pleasure under a churchyard wall: but, on further inquiry, he will find that the building on the island, like those on the shore, is recent, that it stands on the ruins of the Church of St. Cristoforo della Pace; and that with a singular, because unintended, moral, the modern Venetians have replaced the Peace of the Christ-bearer by the Peace of Death, and where they once went, as the sun set daily, to their pleasure, now go, as the sun sets to each of them for ever, to their graves.

§ III. Yet the power of Nature cannot be shortened by the folly, nor her beauty altogether saddened by the misery, of man. The broad tides still ebb and flow brightly about the island of the dead, and the linked conclave of the Alps know no decline from their old pre-eminence, nor stoop from their golden thrones in the circle of the horizon. So lovely is the scene still, in spite of all its injuries, that we shall find ourselves drawn there again and again at evening out of the narrow canals and streets of the city, to watch the wreaths of the sea-mists weaving themselves like mourning veils around the mountains far away, and listen to the green waves as they fret and sigh along the cemetery shore.

§ IV. But it is morning now: we have a hard day’s work to do at Murano, and our boat shoots swiftly from beneath the last bridge of Venice, and brings us out into the open sea and sky.

The pure cumuli of cloud lie crowded and leaning against one another, rank beyond rank, far over the shining water, each cut away at its foundation by a level line, trenchant and clear, till they sink to the horizon like a flight of marble steps, except where the mountains meet them, and are lost in them, barred across by the grey terraces of those cloud foundations, and reduced into one crestless bank of blue, spotted here and there with strange flakes of wan, aerial, greenish light, strewed upon them like snow. And underneath is the long dark line of the mainland, fringed with low trees; and then the wide-waving surface of the burnished lagoon trembling slowly, and shaking out into forked bands of lengthening light the images of the towers of cloud above. To the north, there is first the great cemetery wall, then the long stray buildings of Murano, and the island villages beyond, glittering in intense crystalline vermilion, like so much jewellery scattered on a mirror, their towers poised apparently in the air a little above the horizon, and their reflections, as sharp and vivid and substantial as themselves, thrown on the vacancy between them and the sea. And thus the villages seem standing on the air; and, to the east, there is a cluster of ships that seem sailing on the land; for the sandy line of the Lido stretches itself between us and them, and we can see the tall white sails moving beyond it, but not the sea, only there is a sense of the great sea being indeed there, and a solemn strength of gleaming light in sky above.

§ V. The most discordant feature in the whole scene is the cloud which hovers above the glass furnaces of Murano; but this we may not regret, as it is one of the last signs left of human exertion among the ruinous villages which surround us. The silent gliding of the gondola brings it nearer to us every moment; we pass the cemetery, and a deep sea-channel which separates it from Murano, and finally enter a narrow water-street, with a paved footpath on each side, raised three or four feet above the canal, and forming a kind of quay between the water and the doors of the houses. These latter are, for the most part, low, but built with massy doors and windows of marble or Istrian stone, square-set and barred with iron; buildings evidently once of no mean order, though now inhabited only by the poor. Here and there an ogee window of the fourteenth century, or a doorway deeply enriched with cable mouldings, shows itself in the midst of more ordinary features; and several houses, consisting of one story only carried on square pillars, forming a short arcade along the quay, have windows sustained on shafts of red Verona marble, of singular grace and delicacy. All now in vain: little care is there for their delicacy or grace among the rough fishermen sauntering on the quay with their jackets hanging loose from their shoulders, jacket and cap and hair all of the same dark-greenish sea-grey. But there is some life in the scene, more than is usual in Venice: the women are sitting at their doors knitting busily, and various workmen of the glass-houses sifting glass dust upon the pavement, and strange cries coming from one side of the canal to the other, and ringing far along the crowded water, from venders of figs and grapes, and gourds and shell-fish; cries partly descriptive of the eatables in question, but interspersed with others of a character unintelligible in proportion to their violence, and fortunately so if we may judge by a sentence which is stencilled in black, within a garland, on the whitewashed walls of nearly every other house in the street, but which, how often soever written, no one seems to regard: “Bestemme non più. Lodate Gesù.”

§ VI. We push our way on between large barges laden with fresh water from Fusina, in round white tubs seven feet across, and complicated boats full of all manner of nets that look as if they could never be disentangled, hanging from their masts and over their sides; and presently pass under a bridge with the lion of St. Mark on its archivolt, and another on a pillar at the end of the parapet, a small red lion with much of the puppy in his face, looking vacantly up into the air (in passing we may note that, instead of feathers, his wings are covered with hair, and in several other points the manner of his sculpture is not uninteresting). Presently the canal turns a little to the left, and thereupon becomes more quiet, the main bustle of the water-street being usually confined to the first straight reach of it, some quarter of a mile long, the Cheapside of Murano. We pass a considerable church on the left, St. Pietro, and a little square opposite to it with a few acacia trees, and then find our boat suddenly seized by a strong green eddy, and whirled into the tide-way of one of the main channels of the lagoon, which divides the town of Murano into two parts by a deep stream some fifty yards over, crossed only by one wooden bridge. We let ourselves drift some way down the current, looking at the low line of cottages on the other side of it, hardly knowing if there be more cheerfulness or melancholy in the way the sunshine glows on their ruinous but whitewashed walls, and sparkles on the rushing of the green water by the grass-grown quay. It needs a strong stroke of the oar to bring us into the mouth of another quiet canal on the farther side of the tide-way, and we are still somewhat giddy when we run the head of the gondola into the sand on the left-hand side of this more sluggish stream, and land under the east end of the Church of San Donato, the “Matrice” or “Mother” Church of Murano.

§ VII. It stands, it and the heavy campanile detached from it a few yards, in a small triangular field of somewhat fresher grass than is usual near Venice, traversed by a paved walk with green mosaic of short grass between the rude squares of its stones, bounded on one side by ruinous garden walls, on another by a line of low cottages, on the third, the base of the triangle, by the shallow canal from which we have just landed. Near the point of the triangular space is a simple well, bearing date 1502; in its widest part, between the canal and campanile, is a four-square hollow pillar, each side formed by a separate slab of stone, to which the iron hasps are still attached that once secured the Venetian standard.

The cathedral itself occupies the northern angle of the field, encumbered with modern buildings, small outhouse-like chapels, and wastes of white wall with blank square windows, and itself utterly defaced in the whole body of it, nothing but the apse having been spared; the original plan is only discoverable by careful examination, and even then but partially. The whole impression and effect of the building are irretrievably lost, but the fragments of it are still most precious.

We must first briefly state what is known of its history.

§ VIII. The legends of the Romish Church, though generally more insipid and less varied than those of Paganism, deserve audience from us on this ground, if on no other, that they have once been sincerely believed by good men, and have had no ineffective agency in the foundation of the existent European mind. The reader must not therefore accuse me of trifling, when I record for him the first piece of information I have been able to collect respecting the cathedral of Murano: namely, that the emperor Otho the Great, being overtaken by a storm on the Adriatic, vowed, if he were preserved, to build and dedicate a church to the Virgin, in whatever place might be most pleasing to her; that the storm thereupon abated; and the Virgin appearing to Otho in a dream showed him, covered with red lilies, that very triangular field on which we were but now standing, amidst the ragged weeds and shattered pavement. The emperor obeyed the vision; and the church was consecrated on the 15th of August, 957.

§ IX. Whatever degree of credence we may feel disposed to attach to this piece of history, there is no question that a church was built on this spot before the close of the tenth century: since in the year 999 we find the incumbent of the Basilica (note this word, it is of some importance) di Santa Maria Plebania di Murano taking an oath of obedience to the Bishop of the Altinat church, and engaging at the same time to give the said bishop his dinner on the Domenica in Albis, when the prelate held a confirmation in the mother church, as it was then commonly called, of Murano. From this period, for more than a century, I can find no records of any alterations made in the fabric of the church, but there exist very full details of the quarrels which arose between its incumbents and those of San Stefano, San Cipriano, San Salvatore, and the other churches of Murano, touching the due obedience which their less numerous or less ancient brotherhoods owed to St. Mary’s.

These differences seem to have been renewed at the election of every new abbot by each of the fraternities, and must have been growing serious when the patriarch of Grado, Henry Dandolo, interfered in 1102, and, in order to seal a peace between the two principal opponents, ordered that the abbot of St. Stephen’s should be present at the service in St. Mary’s on the night of the Epiphany, and that the abbot of St. Mary’s should visit him of St. Stephen’s on St. Stephen’s day; and that then the two abbots “should eat apples and drink good wine together, in peace and charity.”10

§ X. But even this kindly effort seems to have been without result: the irritated pride of the antagonists remained unsoothed by the love-feast of St. Stephen’s day; and the breach continued to widen until the abbot of St. Mary’s obtained a timely accession to his authority in the year 1125. The Doge Domenico Michele, having in the second crusade secured such substantial advantages for the Venetians as might well counterbalance the loss of part of their trade with the East, crowned his successes by obtaining possession in Cephalonia of the body of St. Donato, bishop of Eurœa; which treasure he having presented on his return to the Murano basilica, that church was thenceforward called the church of Sts. Mary and Donato. Nor was the body of the saint its only acquisition: St. Donato’s principal achievement had been the destruction of a terrible dragon in Epirus; Michele brought home the bones of the dragon as well as of the saint; the latter were put in a marble sarcophagus, and the former hung up over the high altar.

§ XI. But the clergy of St. Stefano were indomitable. At the very moment when their adversaries had received this formidable accession of strength, they had the audacity “ad onta de’ replicati giuramenti, e dell’inveterata consuetudine,”11 to refuse to continue in the obedience which they had vowed to their mother church. The matter was tried in a provincial council; the votaries of St. Stephen were condemned, and remained quiet for about twenty years, in wholesome dread of the authority conferred on the abbot of St. Donate, by the Pope’s legate, to suspend any o the clergy of the island from their office if they refused submission. In 1172, however, they appealed to Pope Alexander III, and were condemned again: and we find the struggle renewed at every promising opportunity, during the course of the 12th and 13th centuries; until at last, finding St. Donate and the dragon together too strong for him, the abbot of St. Stefano “discovered” in his church the bodies of two hundred martyrs at once!—a discovery, it is to be remembered, in some sort equivalent in those days to that of California in ours. The inscription, however, on the façade of the church, recorded it with quiet dignity:– “MCCCLXXIV. a di XIV. di Aprile. Furono trovati nella presente chiesa del protomartire San Stefano, duecento e più corpi de’ Santi Martiri, dal Ven. Prete Matteo Fradello, piovano della chiesa.”12 Corner, who gives this inscription, which no longer exists, goes on to explain with infinite gravity, that the bodies in question, “being of infantile form and stature, are reported by tradition to have belonged to those fortunate innocents who suffered martyrdom under King Herod; but that when, or by whom, the church was enriched with so vast a treasure, is not manifested by any document.”13

§ XII. The issue of the struggle is not to our present purpose. We have already arrived at the fourteenth century without finding record of any effort made by the clergy of St. Mary’s to maintain their influence by restoring or beautifying their basilica; which is the only point at present of importance to us. That great alterations were made in it at the time of the acquisition of the body of St. Donato is however highly probable, the mosaic pavement of the interior, which bears its date inscribed, 1140, being probably the last of the additions. I believe that no part of the ancient church can be shown to be of more recent date than this; and I shall not occupy the reader’s time by any inquiry respecting the epochs or authors of the destructive modern restorations; the wreck of the old fabric, breaking out beneath them here and there, is generally distinguishable from them at a glance; and it is enough for the reader to know that none of these truly ancient fragments can be assigned to a more recent date than 1140, and that some of them may with probability be looked upon as remains of the shell of the first church, erected in the course of the latter half of the tenth century. We shall perhaps obtain some further reason for this belief as we examine these remains themselves.

§ XIII. Of the body of the church, unhappily, they are few and obscure; but the general form and extent of the building, as shown in the plan, Plate I. fig. 2, are determined, first, by the breadth of the uninjured east end D E; secondly, by some remains of the original brickwork of the clerestory, and in all probability of the side walls also, though these have been refaced; and finally by the series of nave shafts, which are still perfect. The doors A and B may or may not be in their original positions; there must of course have been always, as now, a principal entrance at the west end. The ground plan is composed, like that of Torcello, of nave and aisles only, but the clerestory has transepts extending as far as the outer wall of the aisles. The semicircular apse, thrown out in the centre of the east end, is now the chief feature of interest in the church, though the nave shafts and the eastern extremities of the aisles, outside, are also portions of the original building; the latter having been modernized in the interior, it cannot now be ascertained whether, as is probable, the aisles had once round ends as well as the choir. The spaces F G form small chapels, of which G has a straight terminal wall behind its altar, and F a curved one, marked by the dotted line; the partitions which divide these chapels from the presbytery are also indicated by dotted lines, being modern work.

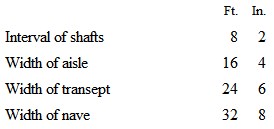

§ XIV. The plan is drawn carefully to scale, but the relation in which its proportions are disposed can hardly be appreciated by the eye. The width of the nave from shaft to opposite shaft is 32 feet 8 inches: of the aisles, from the shaft to the wall, 16 feet 2 inches, or allowing 2 inches for the thickness of the modern wainscot, 16 feet 4 inches, half the breadth of the nave exactly. The intervals between the shafts are exactly one fourth of the width of the nave, or 8 feet 2 inches, and the distance between the great piers which form the pseudo-transept is 24 feet 6 inches, exactly three times the interval of the shafts. So the four distances are accurately in arithmetical proportion; i.e.

The shafts average 5 feet 4 inches in circumference, as near the base as they can be got at, being covered with wood; and the broadest sides of the main piers are 4 feet 7 inches wide, their narrowest sides 3 feet 6 inches. The distance a c from the outmost angle of these piers to the beginning of the curve of the apse is 25 feet, and from that point the apse is nearly semicircular, but it is so encumbered with renaissance fittings that its form cannot be ascertained with perfect accuracy. It is roofed by a concha, or semi-dome; and the external arrangement of its walls provides for the security of this dome by what is, in fact, a system of buttresses as effective and definite as that of any of the northern churches, although the buttresses are obtained entirely by adaptations of the Roman shaft and arch, the lower story being formed by a thick mass of wall lightened by ordinary semicircular round-headed niches, like those used so extensively afterwards in renaissance architecture, each niche flanked by a pair of shafts standing clear of the wall, and bearing deeply moulded arches thrown over the niche. The wall with its pillars thus forms a series of massy buttresses (as seen in the ground plan), on the top of which is an open gallery, backed by a thinner wall, and roofed by arches whose shafts are set above the pairs of shafts below. On the heads of these arches rests the roof. We have, therefore, externally a heptagonal apse, chiefly of rough and common brick, only with marble shafts and a few marble ornaments; but for that very reason all the more interesting, because it shows us what may be done, and what was done, with materials such as are now at our own command; and because in its proportions, and in the use of the few ornaments it possesses, it displays a delicacy of feeling rendered doubly notable by the roughness of the work in which laws so subtle are observed, and with which so thoughtful ornamentation is associated.