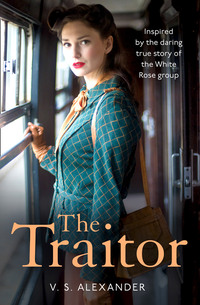

The Traitor

Hans’s father, Robert, was arrested in August for making a derogatory remark about Hitler and was sentenced to four months in prison after being turned in by a woman in his office. Still, Hans went about his medical duties in September and October in his usual careful way, but I could tell he was seething inside about his father’s arrest, as was Alex for a different reason. He went into a period of withdrawal and mourning after Sina’s death. The two of them were like pots about to boil over on a hot stove.

Hans was so stubborn about his resistance to the Reich that he wouldn’t sign a petition for his father’s clemency hearing that his mother had sent along in a letter. His pride was too great to give in to Hitler. He was even so bold as to tell me that he wondered why people feared prison, and, by logical extension, its outcome—death. When he was younger, he had been imprisoned for participating in youth groups that weren’t sanctioned by the Nazis. According to Hans, prison could be a time for reflection, self-assessment, even a religious awakening.

As we struggled through the short days and the long nights of October, we learned that we would be leaving Russia soon. This news depressed Alex because he had grown fond of our homeland, as I had. He promised to keep Russian mud on his boots and confessed that he had kept his vow never to shoot a Russian or a German soldier because he wanted no part of killing.

After we left Gzhatsk, Willi and Hubert met up with us at our assembly point in Vyazma on the thirtieth of October. Despite the reunion, Alex’s sadness at leaving was palpable; his face was sallow, drawn, and careworn, and he moped about like a lost puppy. He told me one day that he suspected that Sina and her children had been imprisoned after the farm had burned. I wanted to tell him what happened, but I feared for both of our lives if the truth came out.

On the first of November, we left Russia for Germany. I was eager to be home, but also anxious because I faced an uncertain future in nursing. My traveling companion, Greta, sensed my reluctance to talk and spent her time flirting with men or gossiping with the other women.

“Did you hear about their adventures?” she asked me one day as we chugged toward Poland.

“Whose adventures?” Of course, she was baiting me with her question.

She flicked at her index finger with her thumb and smiled coyly at me. Her lips were painted flame red, lipstick and powder never far from reach in her leather purse. Men, smoking, and drinking were her weaknesses, but loyalty to her friends, especially those in the Reich, was her strength. The cigarettes and other contraband she obtained so easily led me to believe that she was well acquainted with those in high places in the black market.

“You know who,” she said and pouted. “You spent a lot of time with them.”

I knew perfectly well she was referring to Alex and Hans, but I was determined not to give her the pleasure of prying into my business. She pulled down the window, lit a cigarette with a flourish, and watched as flecks of ash and smoke fluttered away on the wind. The compartment air mixed with the telltale odor of burned tobacco and the cool freshness of the Russian steppe.

“In Gzhatsk, they got into a fight with a few men from the Party,” Greta said. “It was an ugly scene and fists were thrown. They got out of that scrap without being arrested—they must know how to evade the law.” She laughed.

She took another drag and absentmindedly pulled brown specs of tobacco from her pink tongue. Her lips left a bright red smudge around the end of the cigarette.

“How do you know they were in a fight?” I asked.

“People see things,” she said, and leaned forward in her seat as if she was telling me a secret. “And people talk. I’d be careful of the company you keep. I’ve heard they read books they shouldn’t.”

My lips quivered, and I hoped I hadn’t given away my irritation, let alone my annoyance at the implication that the “company” I kept was less than desirable, perhaps even traitorous.

“And they skipped the delousing line in Vyazma to go shopping.” She inhaled and blew the smoke toward my face, but the wind whipped it away. “Now they have a samovar for hot tea anytime they want it. Quite a luxury to spend your hard-earned medic money on.”

We had all gone through the delousing process before boarding the train, but I didn’t recall seeing the men there. Had they gone on a spending spree instead? “It’s none of my business what they do,” I said.

“Ah, but it is your business.” Her lips curled into a cagey smile. “It’s the Reich’s business … everything is the Reich’s business—if we are to win this war.”

I picked up my biology book and ignored her while she finished her cigarette. Greta soon wandered off to find a more personable companion. I read the rest of the evening, before going to bed.

A few days later, at the Polish border, we stopped at the gate. I had a clear view from my opened compartment window on the left side of the train.

Three army guards herded shabbily dressed Russian prisoners into a nearby field. One by one, the guards kicked, spit on, and smashed their rifle butts into the prisoners’ backs.

In a split second, Hans, Willi, and Alex leapt from the car behind me and assaulted the soldiers.

“You son of a bitch,” Willi screamed over the commotion while pummeling one of the guards on the back with his fists. He ripped the rifle from the man’s shoulder and threw it on the ground.

“Keep your hands off them, bastards,” Alex yelled as he confronted another.

Hans, for his part, shoved one of the guards to the ground and kept him pinned there with his foot.

The train stopped only briefly, and by the time the dumbfounded guards knew what had hit them, the cars had started to roll again.

Hans, Alex, and Willi darted for their compartment door as the guards regrouped. I looked back as my three friends, in running turns, clasped the railing and hoisted themselves aboard. Willi was the last in, and, in a final act of defiance, turned round and saluted the guards with his finger.

I took a deep breath and leaned back in my seat. As I feared, Greta had witnessed the incident from another car. When she took her seat across from me, she shot me a look that reinforced her “be careful of the company you keep” attitude. She said nothing, but her furrowed brows and constricted facial muscles revealed all I needed to know about what she’d seen. I was sure she might report them to the SS when we arrived in Munich.

Berlin was only a blur from the train window, a dark and somber city as gray as the autumn weather, its buildings slick and spotted black with rain.

My mother and father welcomed me after I arrived in Munich. While I waited for classes to begin, I pondered what to do with my life. My parents had moved in January of 1940, a little more than a year after Kristallnacht, to a smaller apartment in Schwabing near Leopoldstrasse. This came about for two reasons: The house was closer to the university, where my father felt I belonged, and the rent was cheaper—he had taken a pay cut in his new position as a retail clerk for a German pharmacist.

Many students lived in the district, so the housing turnover was great, making it easier for my parents to find a new apartment, although the building wasn’t as nice as the one we had moved out of. My parents lived on the third floor of a nineteenth-century wood-and-stone structure that had been covered later with white stucco.

Despite settling back into a strained familiarity with my mother and father, I never mentioned the atrocity near the camp. I knew they would be better off not knowing, if the SS knocked on their door. In the Reich, your grandmother was as likely to turn you in as your grandson. Everyone in Germany had that fear—even Nazis knew they had to watch their step.

Since Kristallnacht, my father had kept to himself, preferring to keep his personal and business life private and away from Nazi eyes. My mother suffered under his recalcitrance, and the days and nights of laughter and dance had disappeared. I couldn’t wait to find another living arrangement, paying my own way, allowing me to be on my own and away from my father’s strict silence.

When I did speak of Russia, I told my parents about the happy times with Sina and Alex, my feelings for the country, and my reluctance to continue nursing as a profession, an outgrowth of my experiences at the Front. After seeing the horrors of war firsthand, I told my father that I didn’t have the stomach for it. He strongly suggested I continue in the profession, telling me he wanted a “better life for his grandchildren” than he had given his daughter. The job security would be better than other courses of study, he said. I was touched by his concern for my future, but still undecided. My tales of the Russian Front left my parents wistful, but, like me, caught in the middle of a war. There was no going back to a devastated Russia. Our only choice was to accept what was happening in Hitler’s Germany.

On a Saturday of the break between classes, I met up with my friend Lisa Kolbe, who had been continuing her art and music studies at the university. We decided to visit the Haus der Deutschen Kunst, for it had been many years since I had visited a museum.

Since my parents had moved, Lisa and I hadn’t seen as much of each other as we used to, although we did run into each other occasionally at the Café Luitpold. The trip to the museum was more suited to Lisa’s tastes than mine, but I was happy to do anything to get out of the apartment rather than look through rain-spattered windows on a cold and windy day.

“I can’t be a doctor in the Reich, and I’ve had my fill of nursing,” I complained to Lisa as we climbed the steps to the museum and took shelter under its massive portico on Prinzregentenstrasse near the Englischer Garten. We had met near the Odeonsplatz in the center of Munich, where the memorial to the fallen Nazis of Hitler’s failed Putsch had been erected at the Feldherrnhalle. Walking quickly through the rain, we bypassed the east side of the Feldherrnhalle, with its massive Gothic arches and stone lions, where Germans were required to honor the “martyrs” by giving the Nazi salute, or face arrest.

We shook the rain from our umbrellas and coats and stepped past the museum’s massive doors. The monumental size of the building, one of the first in Hitler’s architectural plan for the Reich, always awed me with its huge galleries, long halls, and tall ceilings with recessed lighting. A solemn woman, wearing a gray suit with a Party pin tacked to it, hair tied back in a bun, took our trappings and handed us our coat check tickets.

“I think you should do what makes you happy,” Lisa announced as we proceeded to the first gallery. “Biology is a good major. Sophie Scholl is studying biology and philosophy.” She was referring to Hans’s sister, whom Lisa had befriended at the university, but I’d not met.

The thought of changing my life’s direction unsettled me, but perhaps Lisa was right. My head whirled as I listened to my internal arguments: obey my father or do what instinct told me was best for me. Since returning from Russia, I’d been haunted by nightmares of the vilest kind: large, festering wounds; severed limbs; decapitations; soldiers with the cruelest injuries; and, the vision I feared most, the slaughter of Sina, her children, and the other Russians. Those horrors played in my mind at night, conjured by my fevered brain. Often I got only a few hours of sleep.

“You look tired,” Lisa said, and smoothed her silvery-blonde hair behind her ears. Her locks had grown longer in the months since I’d seen her, but she looked healthy and pretty in her impish way, her demeanor seemingly unaffected by the war. We walked into the first gallery, where the lighting accentuated her intense blue eyes, upturned mouth, and cheeky smile.

“Still tripe,” she whispered to me as she viewed the artworks and spread her arms in a wide circle. “Goebbels can spout off all day about the ‘triumph of German art,’ but it’s still boring as hell.”

I surveyed the gallery and concluded that Lisa was right despite my limited knowledge about sculpture and painting. The monumental sculptures of naked men shaking hands in comradeship, the boring and classically carved busts that sat like severed heads on pedestals, left me cold and unmoved as if I were standing in a mausoleum rather than a museum. Nothing about the pedestrian Bavarian landscapes, the massive paintings of bucolic German farmers pitching hay, or the tastefully composed female nudes generated an emotion in me. We continued on to an equally boring room.

“We’ve been through a lot,” Lisa said as she observed the paintings, including one of Hitler in battle armor. “Do you remember how excited we were when we first became members of the Young Girls League?”

“Yes, we thought the world would be different and good,” I said.

We sat on one of the tufted benches in the center of the gallery and stared at the grotesque caricature of Hitler attired in gleaming silver, carrying a Nazi flag in his right hand while astride a black horse. It was propaganda at its best—not art—mythologizing, romanticizing a demon who appeared unshakable, invincible.

I shook my head and said, “We were wrong.”

“And then those monotonous stints in the League of German Girls and the Reichsarbeitsdienst,” Lisa said. “Imagine us working on farms and then me teaching children music and art—and you volunteering as a nurse’s aide.” She laughed and flexed her right arm. “At least we got some exercise on the farm.”

“Monotonous is right.” I thought back to the endless days and nights, it seemed, of work, National Socialist stories, home parties to discuss German culture and arts as long as the topics fit the Party’s requirements; days and nights of rules and regulations: no smoking, no makeup, no sexual relations. No, no, no.

“Tell me about Russia,” Lisa said as she looked toward the opposite end of the gallery, where a couple of uniformed soldiers passed through another chamber.

Lisa was my best friend in Munich, but I didn’t want to burden her with my nightmares. I felt somewhat guilty about keeping her in the dark, but my horrible secret had to remain buried. “There’s not much to tell,” I pretended. “Russia was fascinating—wonderful, in fact—the work was depressing and exhausting.” Someday, I knew I’d reveal what I had seen; otherwise, I wouldn’t be able to live with myself.

As if reading my thoughts, Lisa responded, “When the time is right, you’ll tell me … when you’re ready.” She sighed. “Remember how excited we were when our teacher took us to the Degenerate Art exhibit? The president of the Reichskammer called it an ‘exorcism of evil.’ More people attended that exhibit than you’d ever see here. You could drive a Panzer through these galleries and not hit anyone.”

I recalled my feelings on that day in late July 1937 as we toured the narrow, arcaded rooms of the Residenz near the Hofgarten, where the Degenerate Art exhibit had been hastily housed. What a difference from the museum we sat in now! That day we were greeted by the stark wooden figure of the crucified Christ as we climbed the stairs to the first room. His tortured face, the crown of thorns thrusting out from his head, the ribs painfully showing through his emaciated skin, the wound in his side spurting a brown plug of blood, horrified us, but forced us to imagine the pain He had endured. A piece of wood, ugly, yet so supremely powerful in its carving, elicited emotions in us from compassion to revulsion for His suffering.

Our art teacher, Herr Lange, a zealous Nazi, had laughed so hard at the “perverted spectacle” that he’d taken off his horn-rimmed glasses to wipe away tears. A black-coated SS officer, who also happened to be in attendance, congratulated Herr Lange on his good taste and championed him to “teach these young minds a thing or two about good art.” I’d looked at Lisa, and we silently communicated our displeasure at the officer’s remarks. Of course, we couldn’t say anything in opposition to the Reich, or even roll our eyes at the effrontery and stupidity of the SS man and our teacher. I found the art fascinating and many of the pictures touched my emotions with their raw power, particularly the expressive and colorful landscapes, and the arching composition and expressive painting of Franz Marc’s Two Cats, Blue and Yellow.

The exhibit with its abstract forms and geometric landscapes, its misfit subjects, nearly all denigrated with Nazi slogans labeling the art as “effrontery,” “filth for filth’s sake,” blaming the Jew and the Negro for the “racial idea of degenerate art,” sent shock waves through the crowds. One slogan painted on the wall excoriated the artists with the words They had four years’ time—four years to adjust their artistic styles to conform to Hitler’s ideals—four years to cleanse their souls and change their way of thinking.

Many Germans snickered and laughed their way through the exhibit, and I wondered if this response was a true indication of their feelings or a nervous reaction masking their shame. But many held on to their hats or purses and, like sad dogs, skulked their way through the rooms, their blank faces reflecting a deeper despair. They knew. They knew and could do nothing about it.

Lisa nudged me from my reflection and I wondered what I, or we, had done to necessitate such a gesture. I looked at her and she responded by rolling her eyes and flicking her head backward. I glanced to my side and caught sight of a man who had taken a seat behind us on the double-rowed bench. His broad shoulders and muscular back pushed against his jacket and although I only got a glimpse of his face, I judged him to be handsome.

“Yes, this art is wonderful,” I said to Lisa, and with a hurried look acknowledged her cue. “I’m so glad you brought me here.”

“Let’s move on to the next gallery,” Lisa added, and rose from her seat.

A finger tapped my right shoulder. Taken aback, I flinched but turned to face the man. He looked vaguely familiar, bringing up the disconcerting feeling one has of trying to remember an acquaintance from the past. He was handsome with a strong, angular chin, dimpled cheeks, and wide-set blue eyes. Most German women would have considered him an ideal Aryan husband.

Lisa stopped, rooted to her spot on the marble floor.

“Pardon me,” he asked in a charming baritone voice, “do you know where the Josef Thorak sculpture Kameradschaft might be?”

I was of no help because I had little interest in the boring art. Lisa’s mouth narrowed and her blue eyes flashed under her almost white eyebrows. “I don’t know how you could’ve missed it,” she said. “It’s in the gallery behind us, with the other large sculptural nudes.” She pointed to the last room we had been in.

He laughed halfheartedly and smiled. “I’m sorry to have bothered you.” He turned to go but halted, looked back, and said. “Have we met? I believe I’ve seen you both before.”

Suddenly, it struck me who he was; the intelligent, cunning, smile gave him away—I remembered his face from that disturbing day—he had talked to us in November 1938 during Kristallnacht, the day after the destruction.

“On the morning after the synagogues were burned, if I’m not mistaken,” I said. “You stood behind us … and then disappeared.” I recalled the electric jolt of attraction that I felt at the time—one I’d thought he’d sensed as well.

His already dazzling smile brightened and he skirted the bench. “Of course,” he said, and put a finger to his temple as if attempting to recall the memory. “And other times as well … long ago at the Degenerate Art exhibit … and at Café Luitpold.” He walked closer and stopped within an arm’s length of me. “You both have coffee there sometimes? Am I right?”

An uncomfortable, nerves-taut tingle prickled over me. Clearly, he knew much more about us than we knew about him. Lisa stood rigidly by my side, exhibiting the same unease.

“I’m sorry,” he said and bowed slightly. “I’m Garrick Adler. I shouldn’t have been so forward, but it’s rare that I’m in a museum and I found myself wandering—a bit lost.”

He held out his hand, and I shook it, his grip firm and warm.

Garrick approached Lisa and with some reluctance, she shook his hand and said, “You seem to know a lot about us, and we know nothing about you.”

He sat next to me on the bench and encouraged Lisa to sit to his right. “I can remedy that quickly,” he said as Lisa took her seat. “It’s wonderful to sit between two such lovely ladies.”

I cringed. My assessment that he had a wife or many girlfriends apparently had been wrong. “Flattery is unnecessary, Herr Adler. We’re in no need of it.”

Lisa nodded and smiled through clenched teeth, showing her impatience and ready willingness to withdraw from Garrick’s company.

“I’m sure you’d like the Arno Breker sculptures,” Lisa said after her smile settled. “We can guide you to them on our way out.”

“Isn’t he the Führer’s favorite?” Garrick asked in a voice overflowing with sincerity.

“Yes,” Lisa replied, “and he’s fond of Adolf Ziegler’s female nudes as well.”

He swiped his fingers through the voluminous wave of hair flowing away from the part on his head. “Oh, I’ve seen them … very nice.” His eyes glazed a bit in a thoughtful look. “Was your teacher Herr Lange? I must have been a year or two ahead of you, but I could swear I saw you at the Degenerate Art exhibit.”

“So, what do you do?” I asked, trying to steer the conversation away from us. Lisa exhaled and sank against the bench.

“I work for the Reich insurance agency here in Munich. Pretty boring, really, but it makes me feel I’m doing some good for people—keeping those who are ill from falling into poverty and despair.”

“Just like Clara Barton,” Lisa said.

Blood rose to my face.

Garrick jerked his head toward her. “What?”

“Nothing,” Lisa said.

When he turned back to me, rage smoldered in his eyes but subsided as he spoke. “I’ve taken enough of your time—I should be going if I want to see the Thorak sculpture.” He got up from the bench.

Lisa tapped her wristwatch. “We should be going too.”

“Before I leave … I don’t believe I’ve gotten your names.”

“Natalya Petrovich,” I said, “and Lisa Kolbe.”

“It was a pleasure to see you again,” he said and started to raise his hand in the Nazi salute. Instead, his arm fell to his side as if shame, or some other emotion, had caused him to reconsider. “Perhaps I’ll see you at the café.” He walked around the bench and into the gallery behind us.

I scowled at Lisa after he left. “Clara Barton? It probably wasn’t smart to needle him.”

“It was intended as a jab,” Lisa replied. “I doubt if he even knows who she was. I wish you hadn’t given him our names.”

“Why not? It would only make him suspicious if we didn’t.”

“Make something up. He’d never know.”

I shook my head in amazement at her paranoia, but perhaps she was right; we didn’t know Garrick Adler. But why was Lisa so concerned about giving her name? If anything, I was the one who needed to watch what I said after what I’d seen in Russia. “Why don’t you want your name known?”

She shook her head.

“Do you recall seeing Garrick when I was at the Front?” I asked.

“I’ve never seen him, other than after that terrible night in 1938. If he’s seen us, he was spying. We need to be cautious—I don’t trust anyone who can overhear a conversation.”

We left the gallery and strolled through the building until we were back at the entrance. We put on our coats, gathered our umbrellas, and stepped out on the portico. The wind whipped around the stone columns in a cold blast. The rain had slowed to a drizzle, but the gusts rendered the umbrellas useless.

Apparently, Garrick had had his fill of the museum, for I spotted him a block ahead of us, his build and long stride unmistakable.

“It seems he’s headed my way toward Schwabing,” I said. “I’ll see where he goes.”