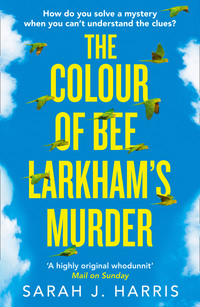

The Colour of Bee Larkham’s Murder

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

Copyright © Sarah J. Harris 2018

Cover design: Claire Ward © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Cover photograph @ Shutterstock.com

Sarah J. Harris asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008256371

Ebook Edition © May 2018 ISBN: 9780008256388

Version: 2018-11-28

Dedication

For Darren, James and Luke

Love also to Mum, Dad and Rachel

Epigraph

‘I could tell you my adventures – beginning from this morning,’ said Alice a little timidly: ‘but it’s no use going back to yesterday, because I was a different person then.’

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll

synaesthesia

noun

1. physiology a sensation experienced in a part of the body other than the part stimulated

2. psychology the subjective sensation of a sense other than the one being stimulated. For example, a sound may evoke sensations of colour

Collins English Dictionary

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

1. Tuesday (Bottle Green): Afternoon

2. Tuesday (Bottle Green): Still That Afternoon

3. Tuesday (Bottle Green): Evening

4. Tuesday (Bottle Green): Still That Evening

5. 17 January, 7.02 A.M.: Blood Orange Attacks Brilliant Blue And Violet Circles on canvas

6. Tuesday (Bottle Green): Later That Evening

7. Wednesday (Toothpaste White): Morning

8. Wednesday (Toothpaste White): Later That Morning

9. Mum’s Story

10. Wednesday (Toothpaste White): Afternoon

11. Wednesday (Toothpaste White): Still That Afternoon

12. Wednesday (Toothpaste White): Still That Afternoon

13. Wednesday (Toothpaste White): Later That Afternoon

14. 18 January, 6.50 A.M.: Marmalade With Cobalt Blue And Crimson Stars on paper

15. 18 January, 3.31 P.M.: Sky Blue Meets Cool Blue on canvas

16. Nan’s Story

17. Wednesday (Toothpaste White): Evening

18. 18 January, 9.02 P.M.: Out With The Old And In With The New on paper

19. Wednesday (Toothpaste White): Later That Evening

20. Thursday (Apple Green): Morning

21. 19 January, 3.18 P.M.: Award-Winning Sky Blue on paper

22. 22 January, 7.02 A.M.: Pandemonium on canvas

23. Thursday (Apple Green): Afternoon

24. 22 January: Dirty Sap Circles on paper

25. 27 January, 4.30 P.M.: Blue Teal And Fir Tree Green on canvas

26. Thursday (Apple Green): Still That Afternoon

27. Thursday (Apple Green): Still That Afternoon

28. 28 January, 5.03 P.M.: Sky Blue Saving Blue Teal on paper

29. Thursday (Apple Green): Still That Afternoon

30. 6 February, 10.04 A.M.: Sky Blue With Muddy Ochre, Cool Blue And Sapphire on canvas

31. 8 February, 9.13 A.M.: Finding Blue Teal Ruined By Aluminium Giggles on paper

32. Thursday (Apple Green): Later That Afternoon

33. 12 February, 7.39 P.M.: Glittering Neon Tubes Harassed By Scratchy Red on canvas

34. Friday (Indigo Blue): Morning

35. 13 February, 8.22 A.M.: Parakeets Disturbed on paper

36. Friday (Indigo Blue): Still That Morning

37. 12 March, 2.23 P.M.: Parakeets Feeding Babies on canvas

38. 24 March, 7.02 P.M.: The Death on paper

39. Friday (Indigo Blue): Afternoon

40. 31 March, 8.01 A.M.: Baby Parakeets on paper

41. Friday (Indigo Blue): Evening

42. 5 April, 1.32 P.M.: Blue Teal Mist Paints Over Sky Blue on paper

43. 6 April, 5.13 P.M.: Sky Blue Paints Over Cool Blue on paper

44. Saturday (Turquoise): Morning

45. Interview: Saturday 16 April, 10.30 A.M.

46. Interview: Saturday 16 April, 10.43 A.M.

47. Interview: Saturday 16 April, 11.01 A.M.

48. Interview: Saturday 16 April, 11.23 A.M.

49. Interview: Saturday 16 April, 11.39 A.M.

50. Interview: Saturday 16 April, 12.15 P.M.

51. Interview: Saturday 16 April, 2 P.M.

52. Interview: Saturday 16 April, 3.10 P.M.

53. Interview: Saturday 16 April, 3.43 P.M.

54. Interview: Saturday 16 April, 4.10 P.M.

55. Interview: Saturday 16 April, 4.24 P.M.

56. Dad’s Story

57. Sunday (Apricot): Morning

58. Sunday (Apricot): Afternoon

59. Monday (Scarlet): Morning

60. Monday (Scarlet): Afternoon

61. Monday (Scarlet): Later That Afternoon

62. Monday (Scarlet): Still That Afternoon

63. Tuesday (Bottle Green): Morning

64. Tuesday (Bottle Green): Afternoon

65. Tuesday (Bottle Green): Later That Afternoon

Epilogue: Three Months Later

References

Acknowledgements

Discover more

About the Author

About the Publisher

TUESDAY (BOTTLE GREEN)

Afternoon

BEE LARKHAM’S MURDER WAS ice blue crystals with glittery edges and jagged, silver icicles.

That’s what I told the first officer we met at the police station, before Dad could stop me. I wanted to confess and get it over and done with. But he can’t have understood what I said or he forgot to pass on the message to his colleague who’s interviewing me now.

This man’s asked me questions for the last five minutes and twenty-two seconds that have nothing to do with what happened to my neighbour, Bee Larkham, on Friday night.

He says he’s a detective, but I’m not 100 per cent convinced. He’s wearing a white shirt and grey trousers instead of a uniform and we’re sitting on stained crimson sofas, surrounded by cream-coloured walls. A mirror’s on the wall to my left and a camera’s fixed in the right-hand corner of the ceiling.

They don’t interrogate criminals in here, not adult ones anyway. Toys sit on a shelf, along with an old Top Gear annual and a battered copy of the first Harry Potter book that looks like some kid tried to eat it. If this is supposed to put me at ease, it’s not working. The one-armed clown is definitely giving me the evil eye.

Would you describe yourself as happy at school, Jasper?

Are you friends with any Year Eleven boys?

Do you know anything about boys visiting Bee Larkham’s house for music lessons?

Did Miss Larkham ask you to deliver messages or gifts to any boys, for example Lucas Drury?

Do you understand what condoms are used for?

The last question’s funny. I’m tempted to tell the detective that condom wrappers look like sparkly sweets, but I recently learnt the correct answer.

It’s SEX: a bubble gum pink word with a naughty lilac tint.

Again, what does that have to do with Bee and me?

Before the interview began, this man told us his name was Richard Chamberlain.

Like the actor, he said.

I haven’t got a clue who the actor Richard Chamberlain is. Maybe he’s from one of Dad’s favourite US detective TV shows – Criminal Minds or CSI. I don’t know the colour of that actor’s voice, but this Richard Chamberlain’s voice is rusty chrome orange.

I’m trying to ignore his shade, which mixes unpleasantly with Dad’s muddy ochre and hurts my eyes.

This morning, Dad got a phone call asking if he could bring me down to the station to answer some questions about Bee Larkham – the father of one of her young, male music students has made some serious allegations against her. His colleagues plan to interview her too, to get her side of the story.

I wasn’t in any trouble, Dad stressed, but I knew he was worried.

He came up with the idea of us taking in my notebooks and paintings. We would tell the police that I stand at my bedroom window with binoculars, watching the parakeets nesting in Bee Larkham’s oak tree. And about how I keep a record of everything I see out of my window.

It’s important the police think we’re cooperating, Jasper, and not attempting to hide anything.

I didn’t want to take any chances, so I stacked seventeen key paintings and eight boxes of notebooks – all filed correctly, their boxes labelled in date order – by the front door.

I hated the thought of them all together in one confined dark place: the boot of Dad’s car. What if the car crashed and burst into flames? My records would be destroyed. I helpfully suggested we divided the boxes and travelled in two separate taxis to the police station, like members of the Royal Family who aren’t allowed to travel together on one plane.

Dad vetoed this and muttered: ‘It might be a good thing if these boxes did go up in flames.’

I screamed glistening aquamarine clouds with sharp white edges at Dad until he promised never to harm my notebooks or paintings. But the damage was done and I couldn’t shake his threat or the colours out of my head; they mixed spitefully behind my eyes. I couldn’t bear to look at Dad or think about the terrible things he was capable of doing.

What he had done already.

Returning to the den in the corner of my bedroom, I rubbed the buttons on Mum’s cardigan until I felt calmer. When I crawled out again twenty-nine minutes later, Dad had packed the car without me. He’d replaced some of my numbered boxes containing records of the people on this street with much older ones from the loft.

You’ve made a mistake, I told him. These are my notebooks from years ago, listing Star Wars characters and merchandise.

Dad said not to worry; the police would probably still be interested in the range of my work and the selection of notebooks could help distract them.

I disliked his explanation. Worse still, when I looked closer in the boot, I realized he’d put box number four on top of box number six.

‘Number four’s carrot orange and sneaky!’ I said. ‘It can’t go on top of dusky pink and friendly number six. They don’t even remotely belong together! How can you not know that by now?’

I wanted to add: Why can’t you see what I can see?

There was no point, there never is. Dad’s blind to a lot of things, particularly involving me. When I was little it was always Mum who understood my colours. But Mum’s gone now and Dad doesn’t want to know.

He let me go back inside so I could spin on the chair in the kitchen rather than run to my den again. We didn’t have time, but we both knew I had to avoid more upset. I felt like an actor, walking around in the shoes belonging to me – Jasper Wishart – ever since the night Bee Larkham …

I couldn’t go there. Not yet.

I had to get the long, snaky ticker tape in my head in order. It had tangled up, with vital bits damaged or jumbled together. I couldn’t figure out how to rejig what had happened back into place.

Being late freaked me out even more. Dad said it’d be OK and not to worry, but that’s what he says whenever we get late-payment reminders for our electricity bills. I’m not sure I can trust his judgement any more.

After I’d double-checked my boxes were settled in the boot, we made sure our seat belts were fastened, because people are thirty times more likely to be thrown from a vehicle if they’re not wearing one.

When we finally arrived, we were fifteen minutes and forty-three seconds late. The desk sergeant told us this wasn’t a problem and we should take a seat, a detective would see us soon.

The desk sergeant’s voice was light copper. I tried not to giggle at the irony. No one else in the police station would understand the joke, apart from Dad, who wouldn’t laugh. He doesn’t find my colours funny.

I longed to fly around the waiting room like a parakeet. Instead, I folded my arms tight and pretended I was a normal thirteen-year-old boy. I stared at my watch. Counting.

Five minutes, fourteen seconds.

The door beeped open, light greyish turquoise circles, and a man in a grey suit came out and shook Dad’s hand without glancing at me.

‘Hello, Detective,’ Dad said. ‘Are you in charge of the investigation into Bee and these boys?’

The man took Dad aside and spoke quietly in muted grey-white lines. He didn’t talk to me or stare.

I overheard Dad tell the detective he doubted I could help because I don’t recognize people’s faces. Something to do with my profound learning difficulties, Dad suspected. He’ll get that assessed at some point.

Did the detective still want to go ahead with the interview? It could be a waste of everyone’s time.

‘Jasper sees colours and shapes for all sounds too, but that’s not much use to anyone either,’ Dad added.

How dare he say that? It’s useful to me because the distinctive colour of people’s voices helps me recognize them. Plus, it’s not just useful, it’s wonderful – something Dad will never understand.

My life is a thrilling kaleidoscope of colours only I can see.

When I look out of my bedroom window, chaffinches serenade me with sugar-mouse pink trills from the treetops and indignant blackbirds create light turquoise lines that make me laugh.

When I lie in bed on Saturday mornings, Dad bombards me with electric greens, deep violets and unripe raspberries from the radio in the kitchen.

I’m glad I’m not like most other teenage boys because I get to see the world in its full multi-coloured glory. I can’t tell people’s faces apart, but I see the colour of sounds and that is so much better.

I was desperate to tell this police officer that while he and Dad can see hundreds of colours, I see millions.

But there are also terrible colours in this world that no one should ever have to witness. Since Friday night I haven’t been able to get some of these ugly tints out of my head, however hard I try.

I longed to disobey Dad and tell this detective that whenever I close my eyes at night the palette becomes even more vivid, more brutal.

That’s because I can’t stop seeing the colour of murder.

TUESDAY (BOTTLE GREEN)

Still That Afternoon

BEFORE WE CAME TO the station, Dad had instructed me to avoid talking about Friday night; I had to stick to what we’d discussed. But when we got there, he was the first person to divert from the plan, not me. Even though they were on the other side of the waiting room, I could hear him firing question after question at the police officer.

‘Is this a formal interview?’ he asked. ‘About young boys visiting Bee’s house?’

Low murmurs rippled from the detective, grey-white noise in the background that floated away as if it didn’t want to draw attention to itself.

‘Oh, OK. Not formal, but a first account about Bee and her relationship with Lucas Drury in particular? That’s it? I’ve tried to explain to Jasper what you might want to ask him, but it’s difficult for someone like him.’

Grey-white lines turned into fluffy clouds and drifted off.

‘Have you tried to get hold of Bee yet?’ Dad went on.

More muted coloured murmurs as the detective’s head moved up and down – something about the police not being able to locate her yet for questioning.

What was a First Account? Why was I really here?

I looked from one man to the other but discovered no clues stamped on their faces. Did Dad and the detective want me to talk about my first impression of Bee Larkham’s voice?

Sky blue.

My memory of our first meeting?

I have a feeling we’re going to be great friends.

Or did they want to know about her first threat?

Do this for me tonight or I won’t let you watch the parakeets from my bedroom window ever again. I’ll stop feeding them unless you do exactly as I say.

I wanted Dad to explain what they were discussing, but he had to fetch the boxes from the car. While we waited, I watched the light dove-grey tapping of my foot and felt the detective’s eyes slice like a knife through my forehead and into my brain as if he knew every detail from beginning to end. The whole ghastly coloured story with no edits.

The waiting room walls closed in on me. I couldn’t breathe. I couldn’t hear anything or see any colours. I forgot the story I had to tell, the one Dad and me had rehearsed for hours at home. Instead, I walked over to the detective, took a deep breath, and began to confess while I had the chance. He remained silent as I told him all about the ring-necked parakeets nesting in Bee Larkham’s oak tree.

They’re incredibly intelligent and musically colourful like a vibrant orchestra. They’ve already got me into trouble with the police and our neighbours but are still my favourite birds in the world.

More importantly I said very loudly and clearly: ‘Ice blue crystals with glittery edges and jagged, silver icicles.’

I didn’t have time to explain these were the colours and shapes of Bee’s screams on Friday night because Dad returned, carrying the first two boxes.

‘Don’t talk without me here, Jasper,’ he said. ‘Sit back down over there.’

A deep line appeared between his eyes. He was annoyed or angry or anxious because I’d launched into the story without him. Dad needn’t have worried. I’d spent three minutes and twenty-three seconds describing the parakeets and their glorious colours, but hadn’t got to the part about hurting Bee Larkham with the sharp, glinty knife and all the blood yet.

Dad’s left eye twitched as he turned to the man in the suit. ‘Art’s his favourite subject at school. He’ll get carried away talking about colours and painting if you let him.’

His muddy ochre voice transmitted a secret warning to me:

Keep quiet or someone will carry you away to a different world.

I returned to the bright orange plastic chair while the detective punched silver coin-shaped numbers into the door panel and disappeared. Dad came back and forth with boxes. I unfolded my arms in case Light Copper thought I looked defensive and had something to hide.

Dad always says that first impressions are important:

Focus on a person’s face and make eye contact otherwise you’ll look shifty.

If this is too difficult, fake eye contact by staring above a person’s eyebrows.

Try to act normal.

Don’t flap your arms.

Don’t rock.

Don’t go on about your colours.

Don’t tell anyone what you did to Bee Larkham.

Remember, that’s not the reason they want to speak to us today.

I was sure I’d impressed the detective. I’d told him the absolute truth. Well, 66 per cent of it. I hadn’t told him everything. I didn’t want to think about the missing 34 per cent.

After three minutes and fifteen seconds, the desk sergeant buzzed us through the door. Dad heaved the boxes into a small room.

A man in a white shirt entered ten seconds later. He looked at me and then up at the camera.

‘Hello, Jasper. Thank you for coming here today. For the record, I’m DC Richard Chamberlain. Also present is Jasper’s father, Ed Wishart. It’s Tuesday the 12 of April and we’re here to discuss an allegation made against your neighbour Bee Larkham.’

His voice was a gross shade of rusty chrome orange.

‘What was your name again?’ I said, shuddering.

‘Richard Chamberlain – like the actor,’ he replied. ‘My one and only claim to fame. Shall we get started?’

We sat opposite each other on the sofas, me shuffling almost off the edge to avoid the vomit-looking stain and Dad yanking me backwards with a hard grip.

My heart had dropped like a huge, glass lift. This wasn’t the first detective I’d met in the waiting room who listened carefully and only spoke in reassuring white-grey murmurs.

This was Rusty Chrome Orange, possibly named after a mysterious actor from some American TV crime show.

I took an instant dislike to him due to:

1. His colour (obviously)

2. He talked about dumb actors and claimed to be famous

3. He stared directly at me

Without warning, he launched into a series of baffling questions about school, my friends and teachers, gifts for boys and condom wrappers that can be disguised as sparkly sweets. But his questions were all wrong from the start – and they haven’t improved.