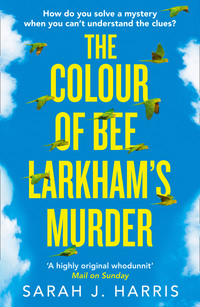

The Colour of Bee Larkham’s Murder

Where’s the grey suited man from the waiting room?

‘I don’t want to be rude, but I hate your colour and I don’t want to talk to you.’

‘Jasper! We discussed this, Son – about being polite and respectful when you answer questions.’

‘Yes, but perhaps the police officer who had grey-white whispers can come back? He seemed to get me. I don’t want Richard Chamberlain like the actor. I want the first detective from the waiting room.’

Silence.

People say silence is golden. They’re wrong. It’s no colour at all.

Rusty Chrome Orange speaks again. ‘That was me, Jasper, in the waiting room. You talked to me about colours and parakeets.’

‘What?’

He picks up his notebook. ‘Ice blue crystals with glittery edges and jagged, silver icicles. You also said that parakeets are incredibly intelligent.’

I glance at Dad to verify Rusty Chrome Orange’s story.

His head moves up and down. ‘You were speaking to DC Chamberlain while I got the boxes from the car.’

I can scarcely believe it. I can’t look at Dad or the detective from the waiting room who has morphed into Richard Chamberlain aka Rusty Chrome Orange. I stare at the grey jacket lying next to the detective on the sofa. He’s taken it off. I didn’t notice him carry the jacket in here.

‘Oh.’ I can’t think of anything else to say. Oh is a small word, exactly how I feel.

Tiny. Insignificant.

Oh. A colour that people can’t see.

‘Sorry, I forgot.’ It’s a lie, of course, but a useful one. Like Sorry, I didn’t see you. I trot it out at least once a day when I don’t recognize someone I’m supposed to.

‘I did try to warn you,’ Dad’s muddy ochre voice says to Richard Chamberlain. ‘He doesn’t recognize me if I turn up at his school unexpectedly.’

He’s right.

I don’t remember Dad’s face.

Richard Chamberlain’s face.

Anyone’s face.

I see them, yet I don’t. Not as complete pictures.

I close my eyes. I hear the muddy ochre of Dad’s voice, but can’t draw together the image of his face in my mind. I couldn’t pick him out of a line-up of men wearing blue jeans and blue shirts – his usual uniform. Is that what Dad’s got on today? I can’t remember. I haven’t paid enough attention.

When he speaks, the rusty chrome orange of Richard Chamberlain’s voice pummels my eyeballs, but if he walked up to me in the street I wouldn’t be able to recognize him unless I’d memorized a distinctive detail: the make of his watch, a hat, socks featuring a character like Homer Simpson or the colour of his voice. Those are the kinds of things I look for first, rather than hair colour or styles that change whenever people run their hands over their heads.

I open my eyes again. None of the usual clues helped me today. Rusty Chrome Orange wasn’t wearing unusual clothes. He tricked me by taking off his grey jacket and whispered, which disguised the genuine colour of his voice with white and grey lines.

Whispers are always frustrating for me because they completely change the hues of people’s voices. Coughs and colds play the same mean trick, which is really sneaky too.

More colourless silence.

It lasts longer than before. I count ten teeth with my tongue before Richard Chamberlain clears his throat, creating an offensive ochre shade.

‘You’ve gone to town on this,’ he says, pointing at my boxes as I perch with one buttock hovering in mid-air over the fried egg-shaped splodge on the sofa.

I sigh. ‘We didn’t go to town. We came straight here otherwise we’d have been even later.’

‘Okaaaaaaaay.’ The rusty chrome orange stretches into an equally unpleasant brownish mud colour.

Richard Chamberlain – call me Richard – clarifies that he’s surprised by how many notebooks I keep and stresses there was no need to bring so many today. He only wants to know if anything I’ve seen might help the investigation.

Before Dad can stop me, I pull out the crucial notebook from box number six and turn to 22 January. This isn’t the true beginning, but it’s an incredibly important day in the sequence of events that followed:

7.02 a.m.

Parakeets land in the oak tree at 20 Vincent Gardens.

Happy, bright pink and sapphire showers with golden droplets.

7.06 a.m.

Man wearing cabbage green pyjamas opens upstairs window of house next to Bee Larkham’s. Shouts prickly tomato red words at parakeets. Clue: Number 22 belongs to David Gilbert.

‘Can we skip forwards?’ Rusty Chrome Orange interrupts, setting my teeth on edge. ‘I’m not sure this is getting us anywhere.’

I sigh. We’re back to where we started, with Rusty Chrome Orange asking the wrong questions again.

If he were a proper detective, he’d have asked me to rewind and start even earlier, from the day it all began: 17 January.

The day Bee Larkham moved into our street.

I guess I understand Rusty Chrome Orange’s impatience. It’s been four days since her murder and he still doesn’t seem to realize she’s dead, but he needs to follow the correct order. I try again with my entry from 22 January, since this part is clear in my head. It’s not confused at all:

8.29 a.m.

Cherry Cords with a dog barking yellow French fries talks to Dad on street. Smoking Black Duffle Coat Man arrives but I don’t hear him speak.

Cherry Cords threatens to kill parakeets using a shotgun. The colour of his trousers, the dull red, grainy voice and the dog give me clues – this must be David Gilbert from number 22.

I don’t know the colour of Black Duffle Coat Man’s voice. I double-check his identity later and Dad says it was Ollie Watkins. I haven’t spoken to him before. He moved back to the street a couple of weeks ago to look after his mum, Lily Watkins, who is dying of cancer at number 18.

I pause and wait for Rusty Chrome Orange to catch up because this is the first sign a murder’s going to happen on our street. But he’s hitting his knee with a pen and has missed the vital clue.

Tap, tap, tap.

A light brown sound with flaky blue-black edges.

I ignore the irritating colour and jump ahead by nine minutes.

8.38 a.m.

Set off for school with Dad, worrying about David Gilbert. He’s lived on our street as long as Mrs Watkins. I ask Dad why he mentioned the shotgun. Dad says he’s a retired gamekeeper and still goes pheasant and partridge shooting every year.

Why oh why isn’t someone trying to stop the potential murderer, David Gilbert?

9.02 a.m.

Arrive at school. Late. Dad tells me not to worry. He’s sorry. Shouldn’t have mentioned David Gilbert’s hobby and former occupation. Forget about it.

9.06 a.m.

Must save parakeets. Concentrate on potential future murderer, David Gilbert from number 22. Dial 999 on my mobile phone in toilet and report death threat.

9.08 a.m.

Operator says—

‘Let’s take a break there, Jasper,’ Rusty Chrome Orange interrupts. ‘I think we should cover this. I can see from our log, this was one of a number of 999 calls you’ve made to the police recently.’ He stops talking and starts again. ‘These calls weren’t emergencies. Unnecessary 999 calls take up police resources, which could be used for proper emergencies. They waste police time.’

Who is this idiot? He’s wasting my time right now, when I could be watching over my parakeets. Maybe the actor Richard Chamberlain is brighter.

‘Of course it was necessary. It was an emergency that day. Don’t you see? I was reporting an imminent threat to life. One you should have taken more seriously if you’d wanted to stop a murder.’

‘Jasper—’ Dad starts.

‘That’s OK.’ Rusty Chrome Orange holds up his hand like he’s directing traffic.

I hope he’s better at that than interviewing me about serious crimes.

‘Your dad’s already explained you suspect someone on your street has killed a few parakeets that nest in Miss Larkham’s front garden.’

‘I know twelve parakeets are dead. Thirteen, if you count the baby parakeet, which died on 24 March, but that was an accident. The other deaths were definitely deliberate.’

Rusty Chrome Orange’s head bounces up and down. ‘I understand you’ve found recent events hard to come to terms with.’

‘Yes,’ I confirm. ‘Murder upsets me.’

‘Stop it, Jasper!’ Dad warns.

Rusty Chrome Orange stops cars again with his hand. ‘It’s OK, Mr Wishart. I can handle this.’

He leans towards me and I almost fall off the cushions to escape from him.

‘Don’t worry, Jasper. We can certainly discuss your concerns about the death of the parakeets. But first, I’d like to talk about your friends: Bee Larkham and Lucas Drury.’

Where did the Metropolitan Police find this man? Is he the last human survivor of a zombie apocalypse? Honestly, I thought this was what we were talking about before he changed the subject abruptly and brought up the massacre of my parakeets.

I should give him another chance, I suppose, even though he’s stupid enough to think Lucas and me are friends. We’ve never been friends. We were Bee Larkham’s friends. Her willing accomplices.

I try again to make him understand. ‘Ice blue crystals with glittery edges and jagged, silver icicles.’ I emphasize the icicles because that’s important. It’s the one thing about Friday night that sticks in my mind. The rest is too blurry; too many blanks and curly question marks, but the icicles’ jagged points remind me of the knife.

‘You’ve told me that twice already, but I’m afraid artists’ colours don’t mean a lot to me,’ Rusty Chrome Orange says. ‘Look, I’m sorry if I’ve confused you. Let’s be clear, none of the boys we’re speaking to are in any trouble or danger. We’re trying to establish a few background facts before we track down Miss Larkham and speak to her ourselves.’

I’m attempting to tell him he’ll never be able to speak to Bee Larkham, but he’s not interested. His voice grates like nails down a blackboard.

‘I want to go home.’

‘Please, Jasper. Concentrate. It’s not for much longer.’ Dad’s muddy ochre has a yellowish pleading tone.

‘I can’t do this. I’m too young. I can’t do this. I’m too young.’

I speak loudly, but Dad doesn’t hear.

‘Jasper’s hardly an ideal witness in your investigation,’ he says. ‘There must be other boys at his school who can assist you? Boys who don’t have as many special needs?’

I need to go home. That’s my special need. My tummy’s hurting. No one’s listening. They never do. It’s like I don’t exist. Maybe I’ve melted away beneath my fingertips into nothing.

‘I understand your concerns, Mr Wishart. I’ll raise them at our case meeting this week, but we need to look closer at Jasper’s relationship with Miss Larkham and Lucas Drury. We believe he may have information that could assist our inquiries. He may have made notes of important times and dates in their alleged relationship.’

‘I doubt it.’

A fluttering of pale lemon.

One of my notebooks protests against Dad’s probing fingers.

‘Look at this entry. The people going in and out of Bee’s house have only basic details: Black Blazer enters, Pale Blue Coat leaves, etc. Jasper has no sense of what they look like, even if they’re teenagers or adults. I doubt he’d be able to identify Lucas or any other boy.’

Dad flicks through my notepad.

‘Most of Jasper’s entries don’t even record people. They’re his sightings of the parakeets nesting in Bee’s tree and other birds. He’s a keen ornithologist.’

Rusty Chrome Orange’s hand dips into a box and pulls out a steel blue notebook with a white rabbit on the front.

‘That’s not right,’ I say, surprised. ‘The rabbit doesn’t belong there.’

‘OK, sorry,’ Rusty Chrome Orange says.

The white rabbit notebook returns to its hiding place in the box.

‘Look at this notebook,’ Dad says, holding up another. ‘It’s all about his colours. How’s that interesting to you? To anyone?’

I want to scream and kick and flap.

Dad doesn’t see my difference in a good, winning-the-X- Factor-kind-of-way. He doesn’t look for the colours we might have in common, only those that set us apart.

I need to hold on. I have to focus on the colour I love most in the world: cobalt blue.

That’s all I’ve got left of Mum – the colour of her voice – but after Bee Larkham moved into our street the shade became diluted. It happened gradually and I never noticed until it was too late.

‘Take me home!’ I say. ‘Now! Now! Now!’

The colour and ragged shape of my voice shocks me. It’s usually cool blue, a lighter shade than Mum’s cobalt blue. Today it looks strange. Is it actually a darker shade than Mum’s? More greyish? I can’t remember. I need to remember her. I want to paint her voice.

‘I have to leave!’

It’s too late. Her colour’s slipping from my grasp, sand through my fingertips. I plaster my hands to my eyes. I want to keep the cobalt blue, vivid, reassuring, behind my eyelids.

Rub, rub, rub.

I want her cardigan. I forgot to bring one of the buttons to rub because I was concentrating on making sure my boxes were correctly ordered.

I glance across the room and the back of my neck prickles. Rusty Chrome Orange told me the mirror was ornamental, like the ship picture on the far wall. He insisted there’s no one behind it, but I can’t trust his colour.

Someone is standing behind the mirror, scrutinizing my face, my mannerisms and laughing at my mix-ups. There are three strangers sitting on crimson sofas on this side of the mirror.

I don’t recognize any of them.

The smallest, the one with dark blond hair who is rocking backwards and forwards, opens his mouth and screams.

Pale blue with violet-tinged vertical lines.

He vomits on the sofa.

Dad’s silent. He doesn’t flick on Radio 2 or tap his fingers on the steering wheel. I guess it’s not surprising, considering the whole embarrassing vomit thing. He’s still angry with me even though Rusty Chrome Orange said not to worry. Lots of kids throw up in that room; the police service employs someone to scrape up their sick. Dad says that’s the deadbeat career I’ll end up with if I don’t work harder to control myself.

The sofa had definitely seen a lot of sick action. What does Rusty Chrome Orange expect when he hangs a trippy mirror on the wall? One minute you think you’re alone and the next you’re surrounded by strangers.

He showed me behind the mirror after I’d calmed down; it was a normal wall.

No hidden window into another room.

No hidden recording devices.

I attempt to block out the dark colours and harsh shapes of the lorries and cars rumbling past. Dad hasn’t said a word since he turned on the engine, marmalade orange with pithy yellow spikes. Maybe he’s not angry with me. Maybe he’s thinking about Bee Larkham.

He knows we both need time to think about what’s happened – me without distractions of unnecessary colours and shapes, him without me banging on about my colours and shapes.

I should try to make him feel better, considering everything he’s done for me. He hasn’t forced me to come out of my den over the last three days except to visit the police station. He rang my school yesterday and said I had a bad tummy ache. At least that wasn’t a lie.

‘Don’t worry, Dad,’ I say finally. ‘I think we did it.’

‘We did what?’ he asks, without glancing back.

‘We got away with murder. Richard Chamberlain – like the actor – knows nothing.’

Dad spits out a yellowish cat-puke word.

I hate swearing. He knows I hate swearing.

He’s getting back at me for throwing up over Rusty Chrome Orange’s sofa.

‘I’m sorry, Jasper. I shouldn’t have used that word. Have you understood anything I’ve told you? Is that what you think’s happened?’

I screw my eyes tightly shut and curl into a ball beneath the seat belt.

Yes, I do. Think. That’s What Happened Back There.

Despite his repeated warnings to keep quiet, I tried to confess. Honestly I did, because I’m very, very sorry about what happened in the kitchen at 20 Vincent Gardens. I deserve to be punished.

Rusty Chrome Orange wouldn’t listen. I doubt he’s going to start looking for Bee Larkham’s body.

Which gives me time.

Time to protect the surviving parakeets. I need longer, around four days until the young begin to abandon the nests in Bee Larkham’s oak tree and eaves and fly far, far away from the dangers lurking on our street.

But I can’t leave.

I can’t ignore the colours any more.

I have to face the truth. I have to remember what happened the night I murdered Bee Larkham.

TUESDAY (BOTTLE GREEN)

Evening

LYING IN BED THAT night, I trace my index finger over the ring-necked parakeet photographs in my Encyclopaedia of Birds. The adult male parakeet is easily identifiable because of the pink-and-black ring around its neck. Females also have these rings, but they’re similar shades of green to their bodies and harder to pick out.

Twelve deaths in total.

Bee Larkham didn’t tell me how many males versus females were slaughtered before she died. I must start a new census before it’s too late. Before the nests are abandoned.

After we got home from the police station, Dad didn’t ask if I felt up to afternoon lessons. While he made cheese toasties and looked for painkillers for my tummy, I grabbed my half-empty bag of seed. I managed to get to the hallway before he stopped me.

Don’t go over to Bee Larkham’s house to feed the parakeets.

Promise?

Don’t put pieces of apple on the ground in our front garden for the birds. It’ll attract rats.

Promise?

No more 999 calls.

Promise?

It’s a pinkish grey word with curly edges, which always gives me a strange, achy feeling inside my tummy – not on the outside where it currently burns like dry ice and looks like a half-open mouth.

I agreed, but had my fingers crossed behind my back, which means it didn’t count. Someone has to feed the parakeets because Bee Larkham can’t do it any more.

Dad doesn’t realize it yet, but Bee Larkham’s house is already attempting to grab attention. The six bird feeders in her front garden have been empty since Friday night. She hasn’t strung up any monkey nuts or put out plates of sliced apple and suet. Bee Larkham didn’t turn on her music to full blast as usual. The parakeets weren’t serenaded and the neighbours didn’t complain about the noise. Earlier today, she didn’t open her front door to the piano and guitar pupils who are allocated forty-five-minute slots after school from 4 p.m. onwards. The house has remained dark and silent since Friday – the Indigo Blue day Bee Larkham died.

I know these Important Facts because I barricaded myself in my bedroom after Dad stopped me leaving the house to feed the parakeets. At first, I concentrated on painting Mum’s voice, but the shades were off. The colours were uncooperative and churlish. That’s the way Dad describes me.

Difficult.

He said he was working from home for the rest of the day, but I could see the colour of the television downstairs while I painted. Half an hour later, when Mum’s true cobalt blue refused to reveal itself and the black-and-silver stripes of the TV became too distracting, I had abandoned my tubes of blue paints and stood at the window with my binoculars.

As usual, I had kept a record of all the relevant activity and used a fresh cornflower blue notebook. I started it especially because it seemed like the right thing to do – to keep my ‘after’ notes separate and uncontaminated from the ‘before’ notes.

3.35 p.m. – Male parakeet flies into branches, berries in beak.

4.02 p.m. – Bee’s piano lesson. Kingfisher Blue Coat Boy two minutes late. Runs up path. Looks at empty bird feeders. Bangs cardboard box colour on door. Door doesn’t open. Kingfisher Blue Coat Boy walks down street.

4.11 p.m. – Five young parakeets together on branch.

4.45 p.m. – Bee’s guitar lesson. Sea Green Coat Boy taps lighter, dusty brown. Door doesn’t open. Sea Green Coat Boy gets back into black car.

Bee Larkham also had an unexpected appointment that wasn’t on her usual teaching schedule.

5.41 p.m. – Dark Blue Baseball Cap Man.

Bang, bang, bang.

‘Open the door, Bee! We need to talk!’ Clouds of dirty brown with charcoal edges.

I was tempted to lean out of my window and shout: Go away and take your clouds with you!

Of course, I couldn’t. I was too afraid of the Dark Blue Baseball Cap Man. I wasn’t sure if I’d seen him before, but knew I didn’t like his colours. Or his baseball cap.

I had scanned the tree with my binoculars. The parakeets remained hidden in the highest branches; even the youngest didn’t draw attention by squawking noisily. Clever birds.

5.43 p.m. – Dark Blue Baseball Cap Man walks backwards down path, staring up at Bee’s bedroom window. Turns around—

The pen had fallen from my hand, making droplets of light, flinty brown on the green carpet. I dived into my den and buried myself beneath the blankets. I stayed in the dark, warm cocoon, running my fingers around the buttons on Mum’s cardigan and smelling the rose scent.

Finally, I crawled out and peeped outside my window. The Dark Blue Baseball Cap Man had gone. 6.14 p.m. I know, because I had double-checked on both my watch and the bedside clock. It’s important to be precise about the details.

I have to record the rest now, one hour and forty-two minutes later at 7.56 p.m., otherwise I’ll never be able to sleep, knowing my records are incomplete. I pick up the blue fountain pen I keep at the side of my bed and start the sentence again. It looks better that way, when my handwriting isn’t panicking and attempting to run off the page. I write:

5.43 p.m. – Dark Blue Baseball Cap Man walks backwards down path, staring up at Bee’s bedroom window. Turns around and sees me watching him with binoculars. He strides towards our house.

?????????????????????????????????

6.14 p.m. – Dark Blue Baseball Cap Man gone.

What happened while I hid for thirty-one minutes in my den? I can’t answer the thirty-three question marks I’ve jotted down.

Did the Dark Blue Baseball Cap Man plan to confront me about my snooping then change his mind? I didn’t hear Dad open the front door. I’d stuck my hands over my ears and sung Taylor Swift’s ‘Bad Blood’ loudly. Still, I’d have heard, wouldn’t I? I’d have seen dark brown shapes, the rapping on our front door.

I’d have heard the colour of voices.

I update my notes:

Who was Dark Blue Baseball Cap Man and what did he want with Bee Larkham?

TUESDAY (BOTTLE GREEN)

Still That Evening