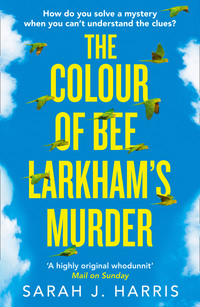

The Colour of Bee Larkham’s Murder

AFTER UPDATING MY RECORDS, I push the notebook beneath my pillow and return to tracing my finger over the male parakeet photo. I don’t want to think about the Dark Blue Baseball Cap Man. I may get nightmares again and they hurt my tummy even when I’ve taken Dad’s painkillers.

I don’t want to think about the blood either, but I can’t help worrying. It hasn’t gone away. Dad’s probably stuffed the knife and my clothes from Friday night behind the lawnmower in the shed at the bottom of our garden. That’s where he hides the sneaky contraband he thinks I don’t know about – emergency packets of cigarettes even though he’s supposed to have given up smoking.

‘Everything OK in here?’ Muddy ochre.

The encyclopaedia tries to escape off my duvet. I manage to catch it in time, ramming my elbow on the pillow to protect my notes. Dad mustn’t find out I’m continuing to make records; I’m keeping secrets. He won’t like to hear about the things I’m remembering.

It’s 7.59 p.m. Dad’s come to say goodnight earlier than usual. A new episode of Criminal Minds must be about to begin on TV.

‘It’s been a tough day, but it’s over now,’ he says. ‘I don’t want you to get worked up about the police. I’ve spoken to DC Chamberlain this evening and taken care of everything. Bee’s someone else’s problem now, not ours.’

I concentrate on the parakeet photos.

‘What about her body?’

Dad sucks in his breath with smoky ochre wisps. ‘We’ve been through this a million times. I sorted everything with Bee. You can stop worrying about her.’

‘But—’

‘Look, I’m telling you she’s not going to bother either of us again. I promise you.’

Silence. No colour.

‘Jasper? Are you still with me?’

‘Yeah. Still here.’ Unfortunately. I wish I wasn’t. I wish I could be a parakeet snuggled deep in the nest in the oak tree over the road. I bet it’s cosy. It used to be a woodpeckers’ nest after the squirrels left, but the parakeets took over the old drey. They always force out other nesting birds like nuthatches, David Gilbert said.

‘Jasper. Look at me and focus on my face. Concentrate on what I’m about to say.’

Don’t want to.

I drag my gaze away from the book in case Dad tries to take that away as well as the bag of seed. I pull his features into a concise picture inside my head – the blue-grey eyes, largish nose and thin lips. I close my eyes and the image vanishes again like I’d never drawn it.

‘Open your eyes, Jasper.’

I do as I’m told and Dad reappears as if by magic. His voice helps. Muddy ochre.

‘I’ve told you already, the police aren’t going to find Bee’s body because there’s no body to find.’

Now it’s my turn to make a funny sucking in colour with my breath. It’s a darker, steelier blue than before.

He’s trying to distance us both from what happened in Bee Larkham’s kitchen on Friday night. Maybe he thinks Rusty Chrome Orange has bugged my bedroom. He could have planted listening devices throughout the whole house. The police do that all the time on Law & Order.

I picture a dark van parked outside our house – two men inside, headphones clamped to their ears, listening to Dad and me talking, hoping we’ll let slip something incriminating about Bee Larkham.

I have to stick to our story.

There is no body.

I repeat the words under my breath.

The police can’t find Bee Larkham’s body if they don’t look for the body and the police aren’t looking for the body, dense Rusty Chrome Orange has proven that. He’s trampled over the Hansel-and-Gretel-style trail of crumbs I left for him, never noticing they lead to the back door of Bee Larkham’s house. They continue into her kitchen and stop abruptly.

I don’t know where the crumbs reappear. Dad hasn’t told me what happened after I fled the scene. Her body could rot for months before it’s found.

If it’s ever found.

There’s no body to find.

‘OK, Dad. If you’re sure about this?’

‘I am. Stay away from Bee’s house and stop talking about her. I don’t want to hear you mention her name again. I want you to forget about her and forget what happened between the two of you on Friday night. No good can come from talking about it.’

I move my head up and down.

Dad’s supposed to know best because he says he’s older and wiser than me. The problem is, whatever Dad claims, it still feels wrong.

I pull out a photo from beneath the book on my bedside table. It’s a new one. Not new, as in someone just took a picture of Mum, which would be impossible. She died when I was nine. I wasn’t allowed to go to the funeral because Dad said I’d find it too upsetting. I haven’t seen this photo before – not in the albums or in his bedside drawer. I found it at the back of the filing cabinet in his study.

I stare at the six people standing in a line. ‘Which one’s Mum?’

‘What?’ Dad’s checking his watch. I’m keeping him from important FBI business. The plots are complicated. He’ll never catch up.

‘Which one’s my mum?’ I repeat. ‘In this photo?’

‘Let me see that.’

I hold the picture up but don’t let him take it off me. He might leave a smudgy fingerprint, which would ruin it.

‘God, I haven’t seen that photo in years. Where did you find it?’

‘Er, um.’ I don’t want to admit I’ve been rummaging in his filing cabinet again and the drawers in his study.

After the parakeets and painting, my next favourite hobby is rooting through all Dad’s stuff when he’s not around.

‘It was stuck behind another photo in the album.’ It’s only a small lie in the grand scheme of things.

Dad’s eyebrows join together at the centre. ‘Wow. This brings back memories. It’s Nan’s seventy-fifth birthday party.’

Interesting, but he hasn’t answered my question.

‘Which woman is Mum?’

He sighs, smooth light ochre button shapes. ‘You honestly don’t know?’

‘I’m tired. I can’t concentrate properly.’ It’s that useful lie again, a trusty friend, like dusky pink number six.

‘She’s that one,’ he says, pointing. ‘At the far right of the photograph.’

‘She’s the woman in the blue blouse with her arms around that boy’s shoulders.’ I repeat it to myself to help memorize her position in the photo.

‘Your shoulders. She’s hugging you. You’re both smiling at the camera.’

I stare at the strangers’ faces.

‘Who’s that?’ I point at another woman, further along. She’s also wearing a blue top, which is confusing.

‘That was your nan. She passed away a month …’ His muddy ochre voice trails away.

I finish the sentence for him. ‘A month after Mum died. Her heart stopped beating from the grief and shock of losing her only daughter.’

Dad inhales sharply. ‘Yes.’ His word’s a jagged arrow, whistling through the air.

I bat away his unprovoked attack. ‘She knew she couldn’t replace Mum. That would have been impossible.’

‘Of course she couldn’t replace Mum. You can’t replace people, like possessions. Life doesn’t work like that, Jasper. You understand that, right?’

Deep down, he must know he’s a liar, but I don’t want to think about that now.

‘What colour was Mum’s voice?’ I say, changing the subject.

Dad checks his watch again. He should have pressed ‘pause’ on the remote before he came up to say goodnight. He’s missed six minutes and twenty-nine seconds of Criminal Minds. A serial killer has probably struck already.

‘You know what colour she was. It’s the colour you always say she was.’

‘Cobalt blue.’ I pinch my eyes shut, the way I did in the police station. It doesn’t work. I open my eyes and stare at my paintings. I’ve lined them up under the windowsill, below my binoculars. They stare back accusingly.

‘Mum’s cobalt blue. That’s what I want to remember about her. Shimmering ribbons of cobalt blue.’

‘That’s her colour,’ Dad says. ‘Blue.’

‘Was she? Was she definitely cobalt blue?’

His shoulders rise and fall. ‘I have no idea. When Mum spoke, I saw …’

‘What?’ I bite my lip, waiting. ‘What did you see?’

‘Just Mum. No colour. She looked normal to me. The way she looked normal to everyone else. Everyone apart from you, Jasper.’

He turns away, but I can’t let Mum’s colour go.

‘I used to talk about Mum being cobalt blue when I was little?’ I press. ‘I never mentioned another shade of blue? Like cerulean?’

‘Let’s not do this now. It’s late. You’re tired. I’m beat too.’

He means he doesn’t want to talk about my colours again. He wants me to pretend I see the world like he does, monochrome and muted. Normal.

‘This is important. I have to know I’m right.’ I kick off the duvet, which is strangling my feet.

‘What am I thinking? Of course she was cobalt blue.’ Dad’s voice is light enough to be swept away by a gentle summer breeze. ‘Don’t get het up about this before bedtime. You need to go to sleep. It’s school tomorrow and I’ve got work. I can’t take another day off. You have to stop thinking about Bee and start concentrating on school. Your stomach looks a lot better, but you need to get your head straight. OK?’

He comes back, leans down and kisses my forehead. ‘Good night, Jasper.’

Four large strides and Dad’s at the door. He closes it to the usual gap of exactly three inches.

He’s told yet another lie.

This isn’t a good night. Far from it.

I wait until I hear the dark maroon creak of the leather armchair in the sitting room before I leap out of bed and snatch up the paintings of Mum’s voice again.

Her exact shade of cobalt blue doesn’t come ready-mixed in a tube. It has to be created. I’ve tried to change the tint by adding white and mixed in black to alter the shade, but everything I attempt is wrong.

If these pieces of art are misleading me, are my other paintings a series of lies too? I sift through the boxes in my wardrobe and retrieve all the paintings from the day Bee Larkham first arrived and onwards. There are seventy-seven in total, which I sort into categories: the parakeets; other bird songs; Bee’s music lessons; everyday sounds.

I’m not worried about these pictures. Their colours can’t harm me.

Not like the voices, which I arrange into separate piles to study their colours in more detail: Bee Larkham. Dad. Lucas Drury. The neighbours.

All the main players.

I painted them to help remember their faces.

Some paintings refuse to get into order. The colours of conversations bleed into each other and transform into completely different hues.

That’s when I finally see what was never clear before. It’s where my problems began and it’s why I can’t get Mum’s voice 100 per cent right: I no longer know which voice colours are right and true, which are tricking me and which are downright liars.

I need to start again. I’ll never know what happened unless I get them right. Until I sort the good colours from the bad.

I wet a large brush and mix cadmium yellow with alizarin crimson paint on my palette.

I feel calmer and stronger. I’m in control. I’m going to paint this story from the beginning – from 17 January – the day it began. My first painting is called: Blood Orange Attacks Brilliant Blue and Violet Circles on canvas.

I will force the colours to tell the truth.

One brushstroke at a time.

17 JANUARY, 7.02 A.M.

Blood Orange Attacks Brilliant Blue And Violet Circles on canvas

THE GRATING BLOOD ORANGE tinged with sickly pinks demanded my undivided attention as three magpies argued noisily with an unidentified bird in the oak tree of number 20’s overgrown front garden. The house had been empty since we’d moved in ten months ago and various species of birds had staked claims to the trees and foliage.

I watched the magpies spitefully flutter and fight through the binoculars Dad had bought me for Christmas. Normally, I used them to spot the birds making colours in Richmond Park during our Sunday afternoon walks: the lesser spotted woodpeckers, chiffchaffs and jays. I couldn’t see what bird the magpies argued with, but I already respected it. Although outnumbered, it bravely held its ground. The bird remained hidden behind a branch, its voice colour drowned out by new, spiky ginger brown shapes.

A large blue van had pulled up outside the house, but the magpies didn’t break off from their vicious attack. A man wearing jeans and a navy blue sweatshirt climbed out and walked up the path to the front door. I thought just one man heaved furniture to and from the van, until I saw two men in jeans and navy sweatshirts carrying a chest of drawers.

I didn’t pay too much attention because two more magpies had landed in the tree. The three bullies had called for backup.

Then, something extraordinary: a parakeet shrieked at the magpies – brilliant blue and violet circles with jade cores – and soared into the sky.

Come back!

I opened my mouth to shout, but my throat was dry with excitement and no words came out. I’d only ever seen parakeets in Richmond Park, never here on my street.

I put my binoculars down and made a note of the parakeet in my light turquoise notebook, where I recorded all the birds I spotted in the park and on our street. I didn’t bother with the magpies. I’ve always disliked their pushy colours.

Across the road, the men continued with their work. Backwards and forwards. They lugged mattresses and boxes out of the house and squeezed them into the back of the van.

I scanned the branches with my binoculars, but I couldn’t spot the parakeet in the trees further down the road. The magpies had flown off too, proving the pointlessness of their territorial battle.

I continued to watch the tree, furious I may have missed another glimpse of the parakeet. When Dad told me it was time for school, I wouldn’t budge from the window. He tried to pull me away, but I screamed until my nose bled down my chest. I didn’t have a clean white shirt because Dad had forgotten to put a wash on again, so we agreed I could stay off school while he worked on a new app design in the study.

Long after the men’s unpleasant-coloured shouts and the sharp yellow spines of the van’s revving engine had died away, the street remained strangely quiet. I didn’t hear the colour of a single chaffinch or sparrow, a car horn beeping or a door slamming.

Maybe I blocked out other noises as I stood guard at the window. I focused on the tree in the front garden of 20 Vincent Gardens, not the house, but I don’t think anyone went in or out. Nothing happened.

It was the calm before the storm; the whole street waited with bated breath for the parakeet to return.

THAT EVENING, 9.34 P.M.

Carnival Of The Animals With A Touch Of Muddy Ochre on canvas

The windows of 20 Vincent Gardens swung open and loud music poured out, like a long, windy snake trailing across the road and up to my bedroom, tap-tapping on the window. Tap-tapping on all the windows in the street.

I’m here. Notice me.

The colours arrived with a bang and drifted into each other’s business, disrupting everything.

Some might call them a nuisance. They certainly did that night and in the weeks and months to come.

The glossy, deep magenta cello; the dazzling bright electric dots of the piano and the flute’s light pink circles with flecks of crimson formally announced that someone new had arrived on the street.

A person as well as a parakeet. They wanted to be seen. They loved loud, bright music as much as me.

Later, much later, I discovered this glorious music was called The Carnival of the Animals. Fourteen movements by Camille Saint-Saëns, a French Romantic composer, who wrote music for animals: kangaroos, elephants and tortoises. I loved the colours of Aviary, birds of the jungle, the most, but that evening was the turn of the Royal Lion.

As soon as the colours started, I jumped off my bed and raced to the window, tearing open the curtains. A woman with long blonde hair held a glass while she threw herself around the sitting room. She danced like me, not caring if anyone else watched. Not caring if she spilt her drink.

Whirling, twirling, she wrapped herself in a brightly coloured shawl of shimmering musical colours, hugging it close to her body.

The colours overlapped and faded in and out of each other on a transparent screen in front of my eyes. If I reached out, it felt like I could almost touch them.

‘Jasper! Turn it downnnnnnnnn …’

The last word was long and drawn out because the sentence never finished, like a lot of Dad’s sentences when he talks to me.

He walked towards me, but I couldn’t turn around. The pulsating music pushed absolutely everything out of my mind. Our house could have burnt to the ground and I wouldn’t have shifted voluntarily.

I thought it was the most perfect combination of colours I’d ever seen. I was wrong, of course. Much better was to come when the pandemonium of parakeets arrived. But I couldn’t know that then.

I focused my binoculars on the house opposite. The colourful music had squeezed out most of the furniture from the sitting room. The sofa, a small table and chairs were pushed up against the walls by the side of a piano. A green beanbag remained, along with an iPod on a stand.

I recognized the dark brown curtains and greyish-white nets that usually hung at the windows folded neatly into squares and placed on the table. They’d been sacked, made redundant.

‘Good God.’ Dad snatched the binoculars off me. ‘What will people think? You mustn’t do that, Jasper. No one likes a spy.’

I didn’t bother to ask what people would think. I’d given up trying to guess the answer to that particular puzzle long ago.

Normally Dad’s grabby hands would have outraged me – it’s rude to snatch. That’s one of the rules he’s taught me. I didn’t remind him because the depth of colours had transfixed me.

They dazzled against the whiteness of the woman’s arms in the background as she waltzed around and around, her floral dressing gown flapping open as if she’d been caught in a sudden breeze.

I couldn’t pull my gaze away to look at Dad.

He was about to explain what I’d done wrong when the music stopped.

‘No! Wait!’ I cried.

The colours vanished as fast as the parakeet from the oak tree. They didn’t drift off or melt away. Gone. Like a TV switched off. But then …

A FEW MINUTES LATER, 9.39 P.M.

Martian Music And Warm, Buttery Toast on canvas

The woman must have heard my shout.

She darted across the room to the beanbag. Bigger, bolder, glittering neon sounds belted out from the iPod.

Martian music.

These colours are alien visitors that only I can understand – colours that people like Dad don’t know exist. They don’t look like they belong in the real world. They only exist in my head – impossible to describe, let alone paint.

Silver, emerald green, violet blue and yellow simultaneously, but somehow not those colours at all.

‘She likes her house music, doesn’t she?’ Dad said. ‘The neighbours will be thrilled.’

It sounded like a question, but I had no answer. I didn’t know who ‘she’ was or what ‘she’ was doing at 20 Vincent Gardens.

Dad’s other choice of words was accurate for once. I was thrilled, along with all the neighbours. Not only did ‘she’ like dancing and loud classical music, she loved Martian music even more.

I sensed we could be friends. Great friends.

‘This won’t go down well,’ he said. ‘She’s already wound up David by parking directly outside his house.’

‘Who is she?’ I asked. ‘Why doesn’t she have any proper clothes? Why did the men take away her furniture in a van?’

Dad didn’t answer. He watched her wild dancing, throwing her hair from side to side. I think he felt sorry for her because she couldn’t afford furniture or curtains. She wore a slippery bright floral dressing gown, which kept wriggling down her shoulders and falling open at the waist. It felt wrong to look at her bare, alien-like skin, with or without binoculars.

This wasn’t the elderly woman Dad said used to live here. This ‘she’ – The Woman With No Name – didn’t remind me of an old person. At all. I don’t normally pay too much attention to hair, but hers was long and blonde and swinging. She moved gracefully around the room, twirling like a ballet dancer or a composer, conducting an orchestra of colour.

‘Who is she?’ I repeated.

‘I don’t know for sure,’ he replied. ‘Pauline Larkham died in a home a few months back. This woman could be a friend or a niece or something. Or maybe she’s the long-lost daughter. I don’t know her name. She’d be about the right age. David mentioned her a while ago. Said she never bothered to come back for Mrs Larkham’s funeral.’

This was news to me. I didn’t know the old woman who used to live over the road was called Pauline Larkham or that she’d died in a new home. Maybe she didn’t like this one much.

‘Well, which one is this woman? Is she a friend or a niece or a long-lost daughter who didn’t come back for the funeral and doesn’t have a name?’

Dad was infuriating. He didn’t grasp the importance of getting the facts straight. I knew one woman couldn’t be two or three people at the same time. She was either someone’s friend or someone had lost her and needed help finding her again.

‘I don’t know, Jasper. Do you want me to ask her for you?’ He fiddled with the strap of the binoculars, which made me itch to snatch them back before he scuffed the leather. ‘It would be neighbourly of us to welcome her to our street, don’t you think? To help her find her feet?’

I stared out of the window, confused. It was obvious where her feet were and she didn’t need his help finding them. She flitted about on the tips of her toes.

I didn’t want to point out the stupidity of his question. Instead of concentrating on her feet, he should have run out of our house and up the path to hers. I could have watched from the window because it was too soon to meet her in person. I hadn’t had time to prepare for the conversation.

Too late!

A man walked up the path to 20 Vincent Gardens, wearing dark trousers and a dark top. I guessed he was a thrilled neighbour, welcoming the new arrival to our street.

He banged hard on the door. Irregular circles of mahogany brown.

The music stopped abruptly.

I instantly disliked this visitor. He’d prevented Dad from introducing himself to The Woman With No Name. Worse still, he’d disrupted her palette of colours.

‘Uh-oh,’ Dad said.

‘Uh-oh.’ I agreed; this man looked like bad news.

The Woman With No Name tied up her dressing gown. Hard. Like she was fastening a parcel at Christmas to deliver to the Post Office. Fifteen seconds later, she appeared at the front door. Her mouth opened wide as if she’d sat down in a dentist’s chair. She took a step backwards, further away from the door. Maybe he wasn’t a thrilled neighbour after all. I didn’t like the way he’d made her mouth change into an ‘O’ shape.

‘Why is she walking backwards?’ I asked. ‘Has he frightened her? Should we call the police?’