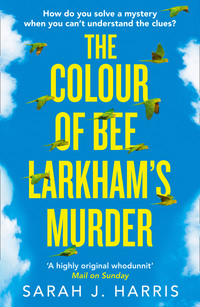

The Colour of Bee Larkham’s Murder

Mrs Thompson and me are always on the same wavelength. She understands patterns and the need for order. I want to tell her there’s a slit in my tummy, like a mouth. As I stand and push my chair back, it opens and closes again; the pain makes silver, pointy stars dance on my skin.

Don’t tell anyone what you did to Bee Larkham.

Keep your mouth shut.

I leave the classroom without replying because I don’t want to lie. I can do it to other people, but not to Mrs Thompson. The truth is, I don’t know how I got hurt. I can’t remember what happened to my tummy. I only recall parts of Friday night. My brain’s blocked out the rest. It’s fuzzy and no distinct colour becomes clear.

My best guess?

I accidentally slashed myself with the knife when I murdered Bee Larkham.

A hand stretches out from the bundle of black trousers and black blazers travelling down the corridor. It thrusts me against the wall. To be honest, I’m surprised I’ve made it this far without being caught.

The boy’s face is indistinguishable from The Blazers accompanying him. I concentrate on his hand instead. It has a telephone number written in blue biro on the skin. Would Lucas Drury’s dad pick up if I rang it? Or his younger brother Lee? Lee used to have electric guitar lessons with Bee Larkham. I enjoyed the range of his colours.

‘Don’t worry,’ I say. ‘I didn’t tell the police anything about you and Bee yesterday, I promise. They only asked me about school friends and condoms.’

‘Are you having a laugh?’ The boy’s face looms at me, his voice a dark nutmeg brown. ‘Why are you talking about bees and condoms?’

I flinch at the spiky turmeric swear word that follows.

‘I, I, don’t know anything,’ I stutter.

The biro hand doesn’t belong to Lucas Drury; his voice is the wrong colour. I have no idea who this is. His shade is similar to lots of boys’ voices in this school. Dull brown, not interesting enough to paint.

I look up and down the corridor, hoping to see someone who isn’t wearing a uniform. I draw a blank. I wish Mrs Thompson would appear, but she’s probably at her desk, marking books. She’s hardworking like that and dead brainy and organized.

‘Damn right you don’t know anything.’ The boy’s hand dives into my blazer pocket and pulls out my £5 note. It’s as if he knew exactly where to find it. How is that possible?

‘That’s mine,’ I whisper.

‘Pardon?’ Biro Hand’s face looms closer. Pasty and acne-scarred.

I hadn’t noticed those details before. I glance away, my eyes pierced by daggers. I need the money to buy seed from the pet shop for the parakeets, but I can’t find my voice. I can’t tell Biro Hand anything.

‘Think of this as a retard tax. It’s money you owe me for getting in my way.’ He pats my pockets down again. ‘Let’s see. Nah. Thought not. As if you’d have condoms! You couldn’t even get a pity shag.’

He pockets my money, whistling yellow-brown spiralling lines and returns to The Blazers. The gang has swelled in size. Their giggles and taunts are thunderclouds of dark grey with streaks of cabbage green.

I don’t try to stop him. No point. He’s twice my size and I won’t be able to wrestle my money off him. Now what am I going to do? I’ve got less than half a bag of seed hidden somewhere at home and no more cash left. I can’t borrow money from Dad; he’ll ask what I want it for.

I can’t admit I’m planning to disobey him and feed the parakeets. I’ll head back to Bee Larkham’s house while he’s working late. Well, technically not her house. Her front garden. I’m not brave enough to go inside. I’m afraid of what I might find.

I walk down the corridor, away from Biro Hand. Too slow. Within seconds, he’s caught up with me again. This time he puts his hand on my shoulder, making me jump. I don’t look at him. His pockmarks make me think of moon craters. If I stare at them, they’ll swallow me up and I won’t be able to climb out again.

‘I don’t have another five-pound note,’ I say.

‘I don’t want your money, Jasper.’ He hisses whitish, almost translucent lines. I can’t identify the true colour. I look down at his right hand. It doesn’t have a phone number written on it.

This isn’t Biro Hand.

He whispers in my ear: ‘I want to know what you’ve told the police about me and Bee Larkham.’

I don’t need to study his face or ask him to raise his voice so I can see the genuine shade. Lucas Drury.

This is the boy at the centre of everything, whose voice is blue teal when he’s not whispering.

It was Bee Larkham’s favourite colour; she liked it far more than my cool blue.

Another uncomfortable truth that revealed itself to me when I least expected it.

‘I know you were at the police station yesterday, Jasper,’ he says quietly. ‘There’s no point denying it. My dad called a copper for an update. He said you came in for a chat with your dad.’

Light Copper makes me laugh, but it could have been Rusty Chrome Orange.

‘This isn’t funny, you idiot. My dad’s gone ballistic.’

‘You told me that last week. You said you were pulling the duvet over his eyes.’

‘The wool, you idiot, and he worked it out. He found my Facebook password and guessed BL is Bee Larkham. He got straight on to the police on Saturday morning and claimed Bee’s a paedophile: a serial offender who preys on young boys. My two sons. Probably more victims. Those were his exact words.’

I breathe out cool blue with white circles. ‘Was he right? Was Bee Larkham a paedophile who preyed on young boys including Lee?’

‘Of course not,’ he says louder. ‘She was in love with me. No one else, but … Never mind about that now. We don’t have time. We’re both in trouble. We have to—’

The bluish green is cut off by shiny conker brown.

‘Lucas! What are you doing? Hurry up!’

Lucas glances over his shoulder as two boys approach. They look like identical twins and must be his friends. They’re not smiling. I’m not sure about Lucas. I haven’t looked at him since he grabbed me. His hand drops from my shoulder as if it’s been burnt.

‘I have to go, Jasper. I’ll meet you in the usual place at lunchtime, OK? We need to get our stories straight before either of us speaks to the police again. Deal?’

I move my head up and down because I agree with him about straight lines and straight stories.

Those are the stories we both need to tell, but I’m not a total fool. Lucas Drury has to go first. He owes me that after everything I had to do for him and Bee Larkham.

MUM’s STORY

THIS IS MUM’S STRAIGHT story, not mine. I was only three or four. I sat with her in the back garden of our house in Plymouth on a late summer evening. Dad wasn’t there. He was with the Royal Marines in Afghanistan or Iraq. I’m not sure which country. No matter. We didn’t need him in the picture when we had each other.

The grass felt warm beneath our bare feet. I don’t remember wriggling my toes in the sunburnt yellow grass, but that’s what Mum said we both did while we played with my red pick-up truck. It had come to rescue the battered yellow car that crashed into Mum’s foot and overturned.

She told me this story over and over again because I was too young to remember it actually happening. She remembered it for me and it became our favourite bedtime story.

‘What’s that?’ I asked.

‘Do you mean the starlings? Look, they’re the noisy birds in the tree over there.’

‘No. I don’t mean those birds. They’re reddish pink. I mean the other sound. Short blue lines.’

A robin hopped out of the hedge, chirping. ‘That one,’ I exclaimed. ‘That’s the colour. A short blue line with moving lemon bits.’

‘You see colours?’ Mum asked. ‘When you hear sounds?’

I said yes, of course I did. Didn’t everyone?

Mum kissed the top of my head over and over again.

‘Not everyone,’ she said, when we finally stopped laughing. ‘Not everyone understands the wonderful way we both see the colour of sounds, Jasper. Which is a shame. A shame for them, not for us, because we share an amazing gift.’

We ran through a list of things, starting with noises we could hear in the back garden like a lawnmower, a car revving, an aeroplane passing overhead and radio music blasting out of a neighbour’s window. I told Mum the colours I saw for every sound.

Lawnmower: shiny silver

Car revving: orange

Aeroplane: light, almost see-through green

Radio: pink

We moved on to other things. The sound of the fan Mum had put in my bedroom to help keep me cool at night (grey and white with flashes of dark ink blue).

Dogs barking: yellow or red

Cats meowing: soft violet blue

Dad laughing: a muddy, yellowish brown

Kettle boiling: silver and yellow bubbles

We talked and talked about my colours and I’d never looked happier, Mum said. My smile stretched from ear to ear.

We could have chatted and played forever, but Mum said it was late and time to have a bath and get changed into my dinosaur pyjamas.

‘Roar!’ I shouted. ‘What colour are dinosaurs’ roars?’

We both decided they were probably shades of purple because that’s the coloured sound my T-Rex made whenever you squeezed his tummy.

Mum swung me up and I settled into my favourite position on her hip.

‘Thank you for letting me into your secret, Jasper,’ she said. ‘Now can I tell you something?’

‘Yes!’ I shouted. ‘T-Rex wants to hear too!’

‘For me, the starlings are bluish green, the robin is bright yellow and the kettle boiling is dark grey with orange bubbles.’ She kissed me quickly on my cheek. ‘Daddy doesn’t like me talking about the colours, so when he gets home you don’t need to tell him about yours either. He’ll be sad he can’t see the world like us, Jasper. Not everyone’s built the same. We’re the lucky ones.’

She was right, but my luck eventually ran out. When Mum died, I lost the one person in my life who could see the world like me.

She loved hearing about my different hues and discovering how they compared to hers.

My colours miss her. They long to be shared with someone who appreciates them as much as I do. But I still have to talk about the shades I see – even to Dad – because a part of Mum lives on through them.

That’s my straight story.

I hate the ending but I can’t change it.

WEDNESDAY (TOOTHPASTE WHITE)

Afternoon

‘IT’S THIS WAY TO the science lab, thicko.’ A hand grabs my collar and hauls me back as I dash out of the dining hall. ‘Lucas said you might make a run for it after lunch. He needs a word.’

I’ll call this boy X.

His evil twin, Y, hovers in the background in case I’m a secret ninja who can kick-box his way out of any situation.

I’m not and I can’t.

They don’t touch me – that would be assault. I’m silently escorted down the corridor. X walks in front and Y behind. No one notices I’m being taken against my will because I’m not screaming. That would be pointless. I doubt anyone would help. Not even the girls who walk past. Especially them. They’d probably laugh buttercup yellow.

When we reach the science lab, Y opens the door and pushes me inside. A boy’s perched on the bench. His lip is cut and there’s a pale green bruise on his cheek and a long, red mark on his hand.

It could be Lucas Drury. Lucas Drury after a fight with a tornado, which has messed up his hair, split his lip and scratched his hand. I didn’t look at his face when we spoke in the corridor earlier, so I can’t know for sure this is the same boy. I don’t say anything. It’s safer that way.

‘Did anyone follow you here?’ His voice is quiet and low. A dark greenish blue colour. Lucas Drury’s colour.

‘Dunno,’ Y says. ‘Don’t think so.’

‘Then what the hell are you looking at? Get out!’ Blue teal.

It’s definitely him.

X and Y’s shoulders go up and down. They slam the door behind them.

I shudder, not only at the unpleasant squashed beetle colour of ‘hell’, but also at the worrying development. I had no idea spies were here at school and on our street – people like David Gilbert who could search for damaging evidence about Bee Larkham and me.

Now I’m certain of one thing: there are spies everywhere.

I gaze at Lucas Drury. He’s trembling with rage at what I’ve done, all the mistakes I’ve made. I rub Mum’s button in my pocket harder as he strides towards me. He’s going to pin me against the wall, like last time. Instinctively, I move backwards. My head is slap bang in the middle of the periodic table poster again. Thulium is on my left, rubidium on my right.

He stops in front of me. ‘Tell me everything.’

I can’t. I don’t want to think about that. I turn my head to look at the poster.

Mendelevium, Nobelium, Ytterbium, Thulium.

‘Hurry up, Jasper. Before someone finds us in here. We need to agree what we tell the police before they question us both again.’

‘Rusty Chrome Orange,’ I say, before I can stop myself.

‘What?’

‘He’s a detective like the famous actor, Richard Chamberlain,’ I blurt out.

‘Wait. You’re confusing me. Who have you spoken to?’

‘Richard Chamberlain wanted a First Account about Bee Larkham, whatever that means. He didn’t explain.’

‘What did he ask you? Did he mention me?’

I reel off the weird questions about Year Eleven boys and Bee Larkham and condoms.

‘What did you tell him?’

‘I told him about the death of my parakeets and my neighbour, David Gilbert, who’s a bird killer, but he wasn’t interested.’

‘Fuck the parakeets, Jasper.’

My scalp prickles at the sharp, ugly-coloured word.

‘Jasper! Open your eyes! You can’t pretend this isn’t happening. This is real. For both of us.’

I don’t want to open my eyes. I don’t want this to be real. I want to shut out the unpleasant colours.

‘I’m not interested in the parakeets and neither are the police. Lee got scared last week and coughed up to Dad about other letters he found in our bedroom. He told him you pass me stuff at school and spy on Bee with binoculars. That makes you a witness in all this.’

He’s lying. I wasn’t spying on Bee Larkham. I was watching her oak tree and making notes of who visited her house and the neighbours’ houses. I thought that would help me build a case against David Gilbert.

‘Please, Jasper. Concentrate. What did you tell the detective about Bee and me? Did you say you’d seen me visiting? Through your binoculars? That you’d seen us together, you know that time …’

Uncomfortable colours nudge around the corners of my brain. I daren’t let them in. Finally, I open my eyes and avoid looking at Lucas. He sounds like Dad. I hate him for that.

Concentrate. Act normal. Don’t flap your arms like a parakeet.

I can’t ever tell him that while he broke a grown-up woman’s heart into millions of tiny, sharp silver pieces, I did something far, far worse to her on Friday night.

Something unforgivable.

‘I didn’t tell Richard Chamberlain, like the actor, anything about you and Bee Larkham.’ That’s the truth. ‘I warned him about the death threats to my parakeets, but my notebooks were out of order. He told me to stop making 999 calls. They waste police time. I screamed and threw up all over his sofa.’

‘Great. Well done. Whatever you’re talking about. Weirdo.’

He punches my arm, not hard. It doesn’t make me cry. Not like when the bigger boys do it after school.

‘Listen, Jasper. I’m denying absolutely everything. The police have nothing, just what Lee thinks he knows and Dad’s suspicions after he found some messages and pics from Bee on Facebook. That’s all. I’m sticking to my story that the note you delivered last week was a prank. It was a dumb girl at school having a laugh.’

‘A prank,’ I repeat.

‘Yes, a prank. Bee didn’t sign the letter with her name. She used initials as usual. They’ve got no proof unless you tell them she gave it to you. You haven’t done that, have you, Jasper?’

‘I didn’t tell the detective anything.’

‘You see. No proof. Dad says the police haven’t been able to get hold of Bee yet and they won’t be able to analyse her handwriting because I ate the letter.’

‘You. Ate. The Letter.’

‘Yup. I tried to make a joke of it when Dad waved it in my face. I grabbed it off him, chewed it up and washed it down with a glass of water before he could pull it out of my mouth. Dad didn’t laugh.’ He touches his split lip. ‘He didn’t find it funny when I refused to tell the police anything about Bee at the weekend.’

‘What did it taste like? The letter, I mean?’

‘You’re missing the point, Jasper. I ate it because I needed to get rid of the evidence. I had to protect Bee. Without that note, Dad has nothing concrete. Nothing that proves we were ever together.’

‘I’m glad you ate it.’ I’m still curious what it tasted like, but Lucas isn’t interested in sharing the details.

‘You have to deny everything too, if they speak to you again,’ he continues. ‘Say the note was from some random girl at school. You don’t know her name. You found it stuffed in your bag or dropped on the pavement outside your house. Or talk gobbledegook about parakeets again to throw them off the scent. Just don’t tell the police the truth about the letters or the time you …’ He stops.

I can’t look at him.

I don’t want to think about that.

I want to be absorbed into the periodic table and create a chemical explosion that annihilates me, Lucas Drury and Bee Larkham and all the putrid colours we created together.

Bang!

Bright flashing lights, splintering acrid yellows and oranges.

I rub Mum’s button harder in my pocket.

‘Look at me, Jasper,’ Lucas says. ‘You have to do this for me. You have to fix this mess because it’s your fault. My dad’s threatening Bee with all kinds of things. She could lose her job and go to prison, all because you cocked up. It’s over between us, but she needs cash from her music lessons more than ever right now.’

He curls up his fist. I close my eyes and wait for him to punch me. I deserve to be hit because I’ve hurt Bee Larkham far worse than his dad ever could. I deserve to go to prison. Maybe this is a trick and Lucas has already guessed what I’ve done.

Maybe her death is written all over my face.

Nothing happens.

I look up. Lucas has walked over to the window.

‘Life sucks,’ he says, wiping a tear from his face. ‘I wish I could go back in time. I’d change everything.’

I agree about time travelling. My life totally and utterly sucks too. I want him to stop crying. Then I’ll pretend I never saw anything; he’ll pretend he never did anything. We’ll both pretend we haven’t seen anything or done anything or know anything about each other.

Most importantly, we’ll both pretend we don’t know anything about Bee Larkham or what went horribly wrong last week.

‘What am I going to do?’ Lucas asks, running his hands over his face. ‘I don’t know what to do.’

I have absolutely no idea. If we were both in a swimming pool, I couldn’t throw Lucas a life buoy because I’m drowning too. I can’t help myself, let alone him.

Lucas doesn’t wait for my non-existent advice.

‘I’m only fifteen. I can’t do it. We were careful – we used protection.’ He looks back at me. ‘Do you think the baby’s even mine?’

WEDNESDAY (TOOTHPASTE WHITE)

Still That Afternoon

WE SPLIT UP LIKE an apple sliced down the middle, spitting out its shiny black pips. I suggested Lucas left the science lab first to prevent any spies reporting our clandestine meeting to the head teacher or police. I waited four minutes, fourteen seconds before heading straight to medical, the only possible destination.

I vomited as soon as I walked in, before the nurse had time to stand up from behind her desk let alone pass a paper bowl. That made me feel even worse, because lately I’ve caused a lot of sick-clearing-up work for people.

I make trouble everywhere I go.

The nurse and me have been arguing for the last five minutes, her dark marigold versus my cool blue.

I can’t let you go home alone. I have to get hold of your dad first.

Dad has an important meeting and can’t be disturbed.

I’ll try again.

He’ll have his phone turned off. I have a key. I can let myself in. I do it all the time. I have neighbours who look out for me.

That’s a lie, but it’s highly unlikely she knows anyone who lives on my street.

I want to hide in my den, away from the accusing windows of Bee Larkham’s house until the bright colours stabbing my brain no longer flash.

I need to get rid of the picture in my head of the baby inside Bee Larkham’s tummy, the baby I killed when I killed Bee Larkham. I’d murdered two people that day, not one like I thought.

I can’t tell the nurse, of course. She’s trying Dad’s number again. My voice is a higher pitch, a whiter, flakier blue.

My tummy hurts. I’ll tell Dad to take me to the doctor’s this evening. We’ll get a sick note. Medicine. I promise.

Bad, horrible thoughts chase each other around my head and make me want to claw at the hole in my tummy while she leaves another message on Dad’s mobile. I can’t get a doctor’s note to fix those feelings.

The truth is, I can’t confess to the nurse. Words jam in my mouth; random thoughts are lodged in my brain. Some can’t get out and others won’t own up to what they’ve done and reveal their true colours.

She won’t understand, how could she?

Her phone rings bubble gum pink and she starts talking again.

I have to get to my den and burrow beneath the blankets. I’ll close my eyes and wrap Mum’s cardigan around me and pretend she’s lying next to me, talking about the colours and shapes she sees when she listens to classical music alone at night while Dad’s away.

The nurse puts the phone down. ‘Wait here, Jasper. A pupil with asthma needs me right away. I’ll find a teaching assistant to stay with you until your dad gets here.’

I do as I’m told.

The door closes and I wait twenty seconds.

I don’t do as I’m told.

I run.

I don’t know how I’ve managed to arrive here. Not at this terrible point in my life, aged thirteen years, four months, twenty-seven days and five hours. I mean the physical journey to my house after running through the school gates – the roads crossed and people passed. I’m grateful my legs kept marching like soldiers rescuing a wounded comrade from behind enemy lines. They moved without me shouting orders.

They carried me all the way back here, to Pembroke Avenue, where I finally stop and catch my breath. My breath is short, ragged lines of sharp blue. My hand and knee throb. A quick inspection reveals I’ve torn my trousers. There’s blood on my knee and a graze on my palm. My tummy’s on fire with pointy silver stars.