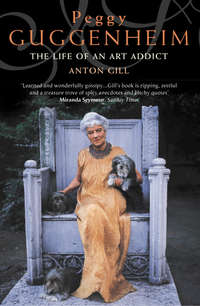

Peggy Guggenheim: The Life of an Art Addict

The hotel had begun to lose money even before Stewart’s death, and Hilton and he believed this was because the Gentile clientele didn’t like the admission of Jews. It wasn’t uncommon for expensive hotels, clubs and even restaurants to refuse admission to Jews in those days, and Saratoga was a major resort for the wealthy. It isn’t clear whether the Seligman family actually went to the hotel in the summer of 1877, or whether they were forewarned: it seems highly unlikely that they would not have booked beforehand. It is possible that Joseph arrived with his family and his baggage in the knowledge that he would provoke a rejection. If so, the humiliation he received must have been half expected. Whatever the truth of the matter, they were rebuffed.

There was a storm in the press, and a furious exchange of letters. Seligman sued Hilton. The liberal elements in society took up Joseph’s cause. But Hilton stuck to his guns: he didn’t like Jews, and they were bad for business. The courts did not find in favour of Seligman, and several other hotels in the Adirondacks, emboldened by Hilton’s move, also introduced a ‘no-Jews’ policy. The only satisfaction Joseph could derive from the affair was the successful boycott of the largest New York department store, also formerly owned by Stewart and now managed by Hilton, which closed as a result. The effect of the case on Joseph was profound: he never recovered from it, perceiving it as the ultimate rejection by a society he had striven all his life to belong to, and into which he had put so much. He died at the end of March 1879, in his sixtieth year. A sad postscript is the resignation as late as 1893 by Jesse Seligman from the Union League Club, his favourite, which his brothers Joseph and William had also been involved in, when, extraordinarily, Jesse’s son Theodore was refused membership on anti-Semitic grounds. Like his older brother, Jesse found that New York was soured for him, and that he had never been truly accepted, even after forty-odd years in the city. He died a year later, leaving $30 million.

While Joseph had sought a wife back home in Germany, and married his cousin Babet, his younger brother James married into one of New York’s oldest and most established Jewish families. The Contents, originally of Dutch-German stock, had been in America since the late eighteenth century. To marry one of them was to gain an entrée into the best circles of Jewish New York society; but that society was small and closed. Despite wealth and respectability, the Jewish élite remained in an unofficial ghetto, without walls or other tangible demarcations to fence it off, but no less real for all that – and it may be that it was one which they did not choose to leave. A disinclination by Gentiles to marry into it was matched by a disinclination to marry out, and even if such a thing had been possible, it would have meant social anathema for the couple involved. The inevitable result was inbreeding. Cousins married cousins, and their children intermarried, so that within a couple of generations physical and psychological problems inevitably occurred.

The Contents looked down on just about everybody, although James was not the first German parvenu to marry one of them. On 4 December 1851, in the presence of Rabbis Isaacs and Merzbacher, he took the hand of Rosa Content. He was twenty-seven, and she was a slender, dark girl of seventeen. They hadn’t known each other long, and didn’t know each other well.

James was easy-going, but he knew the value of money and he was careful with it. Peggy, his granddaughter, describes him as ‘a very modest man who refused to spend money on himself’. Rosa was far from easy-going, and very extravagant. From the first she felt that she had married beneath her, and the wealth the marriage brought did little to mollify her. Throughout her life she would trade on her superiority: she habitually referred to her husband’s family as ‘the peddlers’. The couple’s English butler was also called James. Rosa would call him ‘James’ at all times, and in his presence would refer to her husband as ‘Jim’. This calculated humiliation caused James Seligman great hurt. He wasn’t a good dancer; she was. ‘Germans are so heavy on their feet,’ she complained.

Still, he must have loved her, at least at first, because he indulged her as far as he could bear to, compensating for the expense by stinting himself. His nature led him to take the line of least resistance, and although it was never a happy one, for some time the union worked reasonably well, producing eight children. One of them, Florette, born in 1870, went on to marry Benjamin Guggenheim and become the mother of Peggy.

With time Rosa became increasingly eccentric. As they grew up, the children were not allowed to bring their friends home, on the grounds that they would be of a lower social order ‘and probably germy’. Rosa didn’t like children anyway, not least her own, and her horror of germs was such that she had a habit of spraying everything with Lysol, a practice Florette and Peggy would inherit. She also began to spend more and more of her time shopping. Eventually, James took a mistress. As a result of this, Rosa would astonish shop assistants by asking them out of the blue, and with a dark expression in her eyes, ‘When do you think my husband last slept with me?’

In the end, James could stand it no more and moved out of the family home and into the Hotel Netherland. There he spent his remaining years, and became something of an eccentric himself. He had a horror of new technology, and always had an assistant place his telephone calls. He lived to be ninety-two, and when he died in 1916 he was the oldest member of the New York Stock Exchange. A reporter who interviewed him for the New York Times in his rooms at the Netherland on the occasion of his eighty-eighth birthday found an

old gentleman clad in black, with snow-white, flowing locks and [a] long, spare, white beard, deeply immersed in the contents of a newspaper, his slippered feet extended before him on a velvet hassock. Perched upon his shoulder was a bright yellow canary bird, which sang at intervals, and it fluttered between its open cage and its master.

Rosa, having herself moved to a hotel in the latter part of her life, predeceased her husband, dying of pneumonia at the end of 1907. Peggy remembered her as her ‘crazy grandmother’.

Although Peggy’s Guggenheim uncles and aunts were, with the possible exceptions of her own father and her uncle William, what one might call solid citizens, it is hardly surprising, given their background and their mother’s inbred genes, that the same cannot be said for her Seligman relatives. Despite James’s injection of new blood, despite their tuition as children by the novelist Horatio Alger (though the fact that he’d been sacked by the Unitarian Church for tampering with choirboys may not have helped), Peggy’s Seligman uncles and aunts were all, in her own words, ‘very eccentric’. Unlike her Guggenheim uncles, none of the children of James and Rosa Seligman achieved anything much. They lived on their incomes and lived out their lives. But what lives they were, as Peggy wrote:

One of my favorite aunts was an incurable soprano. If you happened to meet her on the corner of Fifth Avenue while waiting for a bus, she would open her mouth wide and sing scales trying to make you do as much. She wore her hat hanging off the back of her head or tilted over one ear. A rose was always stuck in her hair. Long hatpins emerged dangerously, not from her hat, but from her hair. Her trailing dresses swept up the dust of the streets. She invariably wore a feather boa. She was an excellent cook and made beautiful tomato jelly. Whenever she wasn’t at the piano, she could be found in the kitchen or reading the ticker-tape. She was an inveterate gambler. She had a strange complex about germs and was forever wiping the furniture with Lysol. But she had such extraordinary charm that I really loved her. I cannot say her husband felt as much. After he had fought with her for over thirty years, he tried to kill her and one of her sons by hitting them with a golf club. Not succeeding, he rushed to the reservoir where he drowned himself with heavy weights tied to his feet.

Another aunt, who resembled an elephant more than a human being, at a late age in life conceived the idea that she had had a love affair with an apothecary. Although this was completely imaginary, she felt so much remorse that she became melancholic and had to be put in a nursing home.

There is much more along these lines in Peggy’s autobiography, and there are interesting indications of her own personality in the characters. The operatic Frances was also a good cook and read the ticker-tape, as well as having a mania for Lysol; the morose Adeline’s lover was entirely a figment of her imagination. But the list by no means ends there. Peggy’s uncle Washington Seligman lived principally on whiskey, and charcoal and ice cubes, which he kept in the zinc-lined pockets of a specially-designed waistcoat. This hideous diet was apparently dictated by chronic indigestion, but notwithstanding that and his black teeth, he maintained a mistress in his room in the family house, and threatened to commit suicide if ever the talk turned to her eviction. He was also an inveterate gambler. In the end, in 1912, he did kill himself, not because of the girlfriend, but because he was unable to bear the pain of his indigestion any longer. His father James Seligman, then eighty-eight years old, showed a certain tenderness but shocked the congregation when he walked up the aisle at the funeral service with his late son’s mistress on his arm. Washington’s death was followed by another suicide: a second cousin, Jesse II, shot first his wife, for presumed infidelity, and then himself. Yet another relative, Peggy’s second cousin Joseph Seligman II (old Joseph’s grandson), committed suicide at about the same time because he couldn’t cope with being Jewish. This is a measure of how much strain the Jewish society-within-a-society was under, striving for acceptance from without and riddled with snobbery within.

James’s next two sons were Samuel, who was so obsessed with cleanliness that he spent all day bathing; and Eugene, who was so bright that he was ready for Columbia Law School at eleven, but put it off until fourteen in order to avoid being conspicuous. He graduated with high honours and practised the law subsequently; but he was so mean, a trait he shared with many of his siblings, that he would constantly arrive in their houses unannounced at mealtimes in order to freeload. By way of recompense, he would delight the children of the house after the meal by arranging a line of chairs and then wriggling along them, an act which he called ‘The Snake’.

The remaining brothers were Jefferson and DeWitt. Jefferson married Julia Wormser, a cultivated woman who took Peggy to the opera when she was little, but he neglected his wife and soon left her to live alone in a small hotel apartment on East 60th Street. There he devoted himself to showgirls, or rather, to clothing them. He bought armfuls of dresses and coats from Klein’s Department Store and kept them in the wardrobes in his rooms. When his nieces visited him, he’d invite them to take their pick; on at least one occasion his sister Florette helped herself, saying, ‘I don’t see why I shouldn’t have some too.’ Jefferson had further interesting traits: he considered shaking hands insanitary and advocated kissing instead, and he was a firm believer in the beneficial effects of plenty of fruit and ginger. Every day he would turn up at the Seligman offices (none of James’s sons contributed significantly to the family business) and distribute them to everyone, starting with the partners and working down to the office boys. DeWitt, Peggy’s own favourite, took a law degree but never practised, preferring instead to devote his time to the writing of unactable plays, none of which was ever produced, in which the characters, brought by their creator into impossibly complicated situations, are all invariably blown up at the end – the only way DeWitt could cut through the Gordian knot of his entanglements.

Of the eight children, the ones closest to normality were arguably Samuel, DeWitt and Peggy’s mother Florette. Florette’s eccentricities were slight but palpable. She shared the family trait of meanness, and had a habit of repeating certain words and phrases three times. On occasion she would wear three cloaks, or three wristwatches. There are stories of Florette which sound apocryphal: stopped for driving down a one-way street the wrong way, she told the policeman: ‘But I was only going one way, one way, one way.’ Another time she told a milliner that she wanted a hat ‘with a feather, a feather, a feather’, and was given one with three. Her habit of triple repetition used to drive her husband Ben mad.

A picture emerges of a wan figure, in love with her handsome husband but unable to reach him, and only secure in the strict confines of the society she’d been brought up in, acknowledging its mores and happy not to move outside its social calendar or its topics of conversation. On the other hand, she had the strength to live with her unhappiness over her husband’s infidelities, and to carry on alone for the twenty-five years she survived him, especially in the difficult few years of belt-tightening that followed his death, before her own father’s death rescued her financially. Then at least Florette had shown herself capable of adapting, though nothing in her upbringing had prepared her to fend for herself without the help of servants in even the simplest domestic matters, such as bedmaking, cleaning and cooking. Nor could she pass on any such skills to her daughters. In more important matters of upbringing, too, neither she nor Ben was a good parent; but Ben had been spoilt, and Florette had been given no good example of motherhood. In her eyes, probably the most successful daughter of the three she bore her husband was the oldest, Benita, who conformed to her ideal. Perhaps Benita would succeed in her marriage where Florette had failed in hers.

If Ben and she had been able to be happier together, the story would have been different. Ben, coming from a less strait-laced background, and himself more relaxed than his brothers, might have been able to liberate Florette from the constraints of her upbringing; but by the time he met her it was too late for that, and in any case theirs was a marriage of powerful families as much as of two individuals. Almost as soon as they had set up home together, Ben resumed his philandering. So it was a suffocatingly well-heeled, desperately genteel, and very unhappy world into which Peggy was born.

CHAPTER 4 Growing Up

‘Not only was my childhood excessively lonely and sad,’ Peggy wrote, ‘but it was also filled with torments.’ And again: ‘My childhood was excessively unhappy. I have no pleasant memories of any kind. It seems to me now that it was one long protracted agony.’

She was born on 26 August 1898 at the family home, which was then an apartment in the Hotel Majestic on West 69th Street, New York City. Her parents gave her the name Marguerite, not a family name, but not a Jewish one either, and disguised their disappointment that she was not a son. The Guggenheims had a habit of bearing daughters, to the extent that there was already some mild worry about the future of the surname.

Marguerite would have had a ‘Baby’s Record’ book similar to her younger sister Hazel’s, which is still extant. From it we learn that baby’s first gifts included $500 from Grandpa Seligman, and diamond buttons and a bracelet from his wife. Aunts Fanny and Angie provided a perambulator. Hazel’s nurse was Nellie Mullen, and her first teacher (in 1909) was Mrs Hartmann, who commented, ‘a very clever child’. Baby Hazel’s first word was ‘Papa’. Older sister Marguerite gave her a music box for her first birthday.

Peggy – as she soon became, via her father’s pet name for her of ‘Maggie’ – was the second child. Her sister Benita was nearly three years old, and as soon as Peggy was able to focus emotionally, she settled her affections on Benita, rather than her remote mother and her frequently absent father.

‘She was the great love of my early life. In fact of my entire immature life. But maybe that has never ended,’ Peggy wrote getting on for fifty years later in her autobiography. It’s difficult not to suspect her motives here, because although she and her younger sister both claimed to be rivals for the affection and attention of their older sister, as they did for the affection and attention of their father, it is probably true to say that Ben and Benita provided no more than a focus for a rivalry that was innate between the younger sisters. Both Peggy and Hazel were highly individualistic, both chose unconventional paths through life, and each always wanted to outdo the other – Hazel, as the younger of the two, forcing the rivalry more than Peggy. They were never close. Hazel suffered not only from being the younger, but from having less talent for self-publicity.

Both came to hanker for what the father and the elder sister represented: Ben was a typical absentee father, especially for Hazel, who had not even reached adolescence when he died, and as time went on his increasingly rare and brief visits to the family home, accompanied by presents and an exotic sense of travel, made him a more glamorous figure in their eyes than if he had been a humdrum, day-to-day, office-bound kind of father. Benita took on the standard role of adored older sister. She was more docile and conventional than either of her younger siblings, able to slip uncomplainingly and even gladly into the milieu her mother was at home in. Perhaps that, too, was an object of admiration and even envy for the younger two. There was something else as well: both Ben and Benita died young. A martyr’s death, in these cases through heroism in a shipwreck, and through a striving for motherhood, can attract acolytes. But there are also simpler explanations. Peggy was four and a half when Hazel was born, and ‘I was fiendishly jealous of her’.

Within a year of Peggy’s birth the family had moved out of the Majestic and into a ‘proper’ home. Ben had not yet split with his brothers, the Guggenheim fortunes were riding high, and, with little of the financial caution most of his brothers had learned from their father, he set up his family in style at 15 East 72nd Street, near Central Park. Not only was it an expensive place – Rockefellers, Stillmans, and President Grant’s widow were neighbours – but Ben had it completely redesigned and renovated in the best late-nineteenth-century taste.

Peggy revisited the house with her daughter Pegeen when she returned to America from Europe, after a prolonged absence, in 1941. Her Aunt Cora, to whom it was rented in 1911, still lived there, and Pegeen all but let Peggy down when they were admitted by the butler. As Peggy tells it, ‘When we were in the elevator, my daughter of sixteen, who was accompanying me, suddenly burst out with, “Mama, you lived in this house when you were a little girl?” I modestly replied “Yes,” and to convince her added, “This is where Hazel was born.” My daughter gave me a surprised look and concluded with this statement: “Mama, how you have come down in the world.” From then on the butler, who was ushering us upstairs, looked upon me with suspicion and rarely admitted me to the house. However, my memories alone warranted my admission.’

The house is still there, with its imposing façade. When Peggy lived in it, you entered through a glazed door to a porch, from which further glazed doors led to what Peggy called a ‘small’ lobby, though it had a fountain, dominated by a stuffed bald eagle which her father, strictly against the law, had shot at the family’s summer retreat in the Adirondacks. The eagle had its heraldic broken chains at its feet, which showed either that Ben had a keen sense of irony, or none whatsoever.

The vestibule, marble-clad, contained a marble staircase which led to the piano nobile, where a large dining room ‘with panels and six indifferent tapestries’ looked southwards, while to the rear there was a small conservatory. The main floor also contained a reception room dominated by another tapestry, of Alexander the Great, and here it was that Peggy’s mother gave a weekly tea-party for the other ladies of the New York Jewish haute volée. Peggy, forced to attend these functions as a child and already feeling rebellion stirring within her, found them excruciatingly boring. This is not hard to understand, because the conversation, informed by the participants’ obsession with social standing and correctness, was always about which people were on or off the visiting list, the quality of one’s silver – it should be heavy but not look heavy – the quality but lack of ostentation of one’s dress, what jewels to wear, what colleges were really acceptable for one’s sons (Harvard and Columbia yes, Princeton no), and so on. Also important was whom to marry, and whom not to. You couldn’t marry a Gimbel or a Straus, because they were ‘storekeepers’. At the same time, because Gimbel’s and Macy’s were great rivals, no Gimbel ever married a Straus either. Then there was the question of the ‘old’ New York Jewish families and the ‘new’ ones – approximately pre- and post-1880 – a stratified snobbery which mirrored the English concept of ‘old’ and ‘new’ money, and which still exists today. The Guggenheims, arriving in New York relatively late, after the older Jewish clans had already formed their group, had to contend with this despite their wealth.

The chronicler of Jewish New York of the time, Stephen Birmingham, paints a telling picture of this closed society:

In the evenings the families entertained each other at dinners large and small. The women were particularly concerned about what was ‘fashionable’, and why shouldn’t they have been? Many of them had been born poor and in another country, and now found themselves stepping out of a cocoon and into a new and lovely light. They felt like prima donnas, and now that their husbands were becoming men of such substance, they wanted to be guilty of no false steps in their new land. They wanted desperately to be a part of their period, and as much as said so. Beadwork was fashionable. One had to do it. It was the era of the ‘Turkish corner’, and the ladies sewed scratchy little beaded covers for toss pillows. At one dinner party, while the ladies were discussing what was fashionable and what was not, Marcus Goldman rose a little stiffly from the table, folded his heavy damask napkin beside his plate, and said, ‘Money is always fashionable’, and stalked out of the room.

In her reaction to all this, shared with her father who, significantly, not only got out of it, but returned to a much more relaxed Europe, specifically France, Peggy’s individualistic nature found itself – and she was a rebel too, though a reluctant one. Hers was a mixed nature and a mixed nurture: she was born into a nouveau riche bourgeoisie, but she had peasant roots. She never succeeded in shaking off either influence, though she had more success with the former, which was imposed, than with the latter, which was inborn.

The first floor of the house contained a further grand room – a Louis XVI ‘parlor’, complete with mirrors and more tapestries. Even the furniture was covered in fake tapestry material, and every window in the house was draped with claustrophobic lace curtains in the German manner. Reading between the lines of Peggy’s reminiscences, one can sense the repugnance she felt even as she wrote her descriptions almost half a century later. The parlour also contained a bearskin rug, whose snarling, open red mouth still contained its teeth and a plaster replica of its tongue, which kept breaking off, giving the head a ‘revolting appearance’. The teeth worked loose from time to time as well, and had to be glued back in.

But this room and this floor contained poignant memories for Peggy. Apart from the moth-eaten bearskin, ‘There was also a grand piano. One night I remember hiding under this piano and weeping in the dark. My father had banished me from the table because, at the tender age of seven, I had said to him, “Papa, you must have a mistress as you stay out so many nights.”’ This innocent but perceptive remark was undoubtedly true, and in its precocious directness it gives a foretaste of the person Peggy was going to grow up to be. But there is another, pleasanter memory, which is described with keenly remembered yearning: ‘The center of the house was surmounted by a glass dome that admitted the daylight. At night it was lit by a suspended lamp. Around this was a large circular winding staircase. It commenced on the reception floor and ended on the fourth floor where I lived. I recall the exact tune which my father had invented and which he whistled to lure me when he came home at night and ascended the stairs on foot. I adored my father and rushed to meet him.’