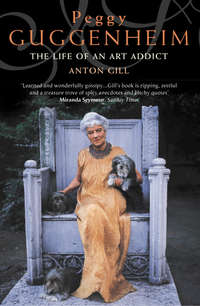

Peggy Guggenheim: The Life of an Art Addict

The same year, her grandfather James Seligman died, and with what he willed Florette the family’s fortunes improved. They moved to 270 Park Avenue, near the corner of 48th Street. Here Peggy’s wild streak led her into more trouble: ‘My mother permitted me to choose furniture for my bedroom, and I was allowed to charge it to her. But unfortunately I disobeyed her and went shopping on the sacred Day of Atonement, the great Jewish holiday Yom Kippur. I had been expressly warned not to do this and I was heavily punished for my sin.’ Her mother refused to pay for the furniture. Benita bailed her out, and not only that, she stood her a makeover at Elizabeth Arden.

The United States entered the First World War in April 1917, but before that Peggy had already been supporting the war effort. She began knitting socks for soldiers, and the activity became an obsession. She took her knitting with her wherever she went, even to dinner and to the theatre. Before his death, her aged Seligman grandfather had complained at the expense of all the wool she bought. On a vacation to Canada she missed most of the scenery because she sat in the back of the car and knitted. Her attention was distracted only twice: by the nice Canadian soldiers in Quebec, and on the way home when, as Jews, the family was refused more than overnight accommodation (obligatory by law) at a Vermont hotel.

Peggy took an official war job in 1918. Her duty was to advise and help newly-recruited young officers to buy uniforms and equipment at the best rate – a job for which her family contacts made her eminently suitable. She shared it with a close schoolfriend, who dropped out owing to illness. Peggy took on her workload, and with what was becoming typical application – anything to keep away from those suffocating salons – she overworked herself into a nervous breakdown. It’s more than possible that her imagination cued the thought that some of the young men she was equipping would never return. Sent to a ‘psychologist’, she told him she thought she was losing her mind. ‘Do you think you have a mind to lose?’ quipped the doctor, who evidently had not yet read the recently translated works of Freud. But Peggy provided a serious comment on the encounter, which gives a significant key to the future workings of her mind: ‘Funny as his reply was, I think my [concern] was quite legitimate. I used to pick up every match I found and stayed awake at night worrying about the houses that would burn because I had neglected to pick up some particular match. Let me add that all these had been lit, but I feared there might be one virgin among them.’

Florette asked her late father’s nurse, a Miss Holbrook, to look after her disturbed daughter. Slowly, this sensible woman weaned Peggy off what had become a fantasy-identification with Dostoevsky’s Raskolnikov, and brought her back to what passes for most of us as normal. During this psychological rite of passage, however, Peggy had – if she can be believed – become engaged to a pilot yet to be transferred overseas. But she adds: ‘I had several fiancés during the war as we were always entertaining soldiers and sailors.’

Peggy turned twenty in August 1918, and two and a half months later the war came to an end. New York society settled back with relief. The fight was over, the danger was past, and the USA was much too far away from the carnage to have suffered any physical damage. Except for the bereaved families of the fallen, the distant European war seemed unreal – an awful event, better forgotten; and Jewish Germans were most anxious that no taint of the Kaiser should attach to their names.

In one more year Peggy would reach her majority. Then she could really spread her wings.

CHAPTER 5 Harold and Lucile

Although there wasn’t a general penchant for marrying well-placed Englishmen among the Guggenheim girls, several did manage it. There was a pronounced anglophilia in some branches of the family. Uncle Solomon adored Great Britain. He went grouse-shooting in Scotland and set up his aristocratic elder son-in-law as a beef farmer in Sussex by giving his daughter Eleanor what she later described as a ‘useful little cheque’. Eleanor married Arthur Stuart, the Earl Castle Stewart (the family seat was in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland, until it was blown up by the IRA in 1973), and lived most of her life in England, a pillar of the Women’s Institute and a great contrast to her cousin Peggy, though one of her sons recalls that she had even less time for Hazel. Solomon’s daughter Barbara married Robert J. Lawson-Johnston, who, though brought up as an American citizen, had been born in Edinburgh (he was the son of the founder of the company that makes Bovril) and educated at Eton. Their son Peter was later raised to the captaincy of the Solomon Guggenheim concerns by his mother’s cousin Harry.

Uncle Solomon’s third daughter, Gertrude, also lived in England, in a house specially built for her by her father – Windyridge in Sussex, where Eleanor’s son Simon now lives – though few concessions were made for her in its design. Gertrude was disabled and well below average height. She gave her life to good works; during the Second World War she took in evacuees, and she habitually made it possible for underprivileged children from London’s East End to take summer holidays with her in the country. ‘She used to take them through the millpond to get the lice off them,’ her nephew Patrick, Earl Castle Stewart, remembers.

This love of Britain and Ireland was partly motivated by a desire to disguise Jewish mainland European peasant antecedents, and went along with the desire to assimilate, to cease to be the target of anti-Semitism, against which no amount of wealth was proof. Within the society in which Peggy grew up, the marriage one made was crucial. It’s probable that Florette and Ben, though less conventional than Ben’s brothers, wished for similar marriages to those their cousins had made, for their three daughters. And Peggy and Hazel did grow up to feel a great affection for England.

But marriage was the last thing on Peggy’s mind in 1918, and already she was showing signs of having no intention of following her mother and older sister into the social round of the New York Jewish upper crust. One influence in particular must have made Florette shudder, yet it was one which profoundly shaped Peggy’s thinking, though she was never overtly political, at least until her middle years. Religious belief never played any role in her life whatsoever.

After her couple of years at the Jacoby School were over, Peggy was at a loose end. Her active mind had been stimulated in a way which could never now be satisfied by the narrow bounds of the society into which she had been born, and she took private courses in economics, history and Italian. Through them she met a teacher called Lucile Kohn.

Kohn was Peggy’s first mentor. In her mid-thirties by 1918, she had initially been a supporter of the Democratic President Woodrow Wilson, but, becoming disaffected with him during his second term of office, she had embraced the Socialist cause. Kohn may have seen a disciple in the rebellious teenager before her, a poor little rich girl from a conservative background; but if she did, she sought to persuade by example rather than by proselytisation. Kohn was a pragmatic Socialist, believing that Socialism was the only way to improve the lot of humankind. Peggy was not an immediate convert, but Lucile planted seeds in her mind which would grow and bear fruit in the future, though not in the way the teacher imagined. Later on, when Peggy had come into her inheritance and moved to Europe, she sent Kohn ‘countless $100s’. Kohn was the first of many individuals whose talent Peggy thought worth supporting for a greater or lesser period of their lives, and Peggy’s subsidy changed Kohn’s life more than Kohn’s influence changed hers, for it enabled her to devote herself to her chosen cause full-time. ‘As I look back over my long life (ninety years) I list the few people who made a tremendous change in my life,’ Kohn wrote to Peggy in 1973, ‘– a change for the better – and Peggy Guggenheim is one of the four.’ She told Virginia Dortch, ‘I really think we learned and felt together that people like the Guggenheims had an obligation to improve the world.’ This was an obligation to which the Guggenheims responded through a number of foundations and trusts set up when the various family fortunes had been made.

Peggy was politically influenced by Kohn, but still she didn’t know what to do with herself. Together with a desire for education had come a desire to work, to occupy her life positively. She had had a run of boyfriends – whom, as we’ve seen, she called ‘fiancés’ – during the war, but she was dismissive of them. Benita’s marriage in 1919 to an American airman, Edward Mayer, who had just returned from Italy – a marriage of which Florette disapproved because Mayer did not come from the right background and had only a modest fortune – only affected Peggy in the sense that she felt abandoned by her sister. She disliked Mayer, and is profoundly unkind about him in her autobiography, though she was a witness at the City Hall wedding, together with a lifelong friend, also called Peggy (who would later marry Hazel’s second husband after his divorce and one of the most traumatic episodes in the entire Guggenheim family story). Benita and Edward, who seems to have been, if anything, rather strait-laced, had a successful marriage, marred only by Benita’s inability to have children. The marriage ended only with Benita’s untimely death in 1927, following another unsuccessful pregnancy. Edward was even blamed for this, since it was felt that Benita should not have been permitted to try again for a child.

An outlet for Peggy’s energies still didn’t suggest itself, and in the summer of 1919, passing her twenty-first birthday, she came into the money she was due to inherit from her father. The timing was good, for it was seven years since Ben’s death, and it had taken her Guggenheim uncles exactly that long to sort out his affairs. Half of the inheritance had to be maintained as capital in trust. The uncles sensibly suggested that the entire amount be absorbed into the Trust Fund, and Peggy just as sensibly agreed, with the result that her capital yielded an income of about $22,500 a year – not bad in those days, even for a ‘poor’ Guggenheim.

Hitherto in 1919, apart from Benita’s wedding, the only major excitement had been winning first prize at the Westchester Kennel Club dog show with the family Pekinese, Twinkle – one of the first of many small dogs that Peggy would keep throughout her life. Now, things could really take off. Above all, she was legally independent, and could free herself of her mother’s influence – much to Florette’s distress.

Peggy decided to embark on a grand tour of North America, taking as her companion a female cousin of Edward Mayer. They travelled to Niagara Falls, and thence to Chicago and on to Yellowstone National Park. After that they spent time in California, visiting the nascent Hollywood, which didn’t impress her: she dismissed the film industry people she met as ‘quite mad’. Then they dipped into Mexico, before travelling north along the west coast all the way to Canada. From there they returned to Chicago, where they rendezvoused with a demobbed airman, Harold Wessel, whom Peggy described as her fiancé. He introduced her to his family, whom she proceeded, perhaps deliberately, to insult, telling them with typical forthrightness that she found Chicago, and them, very provincial. As she prepared to leave on the train to New York, Wessel broke off the engagement, which didn’t cause Peggy distress. She probably only became engaged to him to copy Benita, and was relieved to get out of it.

Peggy’s allusions to fiancés and boyfriends and romantic – though still platonic – attachments are frequent and insistent enough to make one suspect that she was either protesting too much or trying to prove to herself that she was genuinely attractive to the opposite sex. If that were the case, the cause is not far to seek. All three sisters had been very pretty children, but while Benita and Hazel grew into beautiful women, Benita with a placid temperament, Hazel with an unruly and scatterbrained one, Peggy lost the early delicacy of her looks. With her lively eyes and a personality to match, her long, slim arms and legs, and her too-delicate ankles, her attractiveness was not in doubt; but she had one very serious flaw: she had inherited the Guggenheim potato nose. Now she decided to have something done about it.

Plastic surgery wasn’t perfected until the Second World War, was in its infancy early in 1920, when Peggy went to a surgeon in Cincinnati who specialised in improving people’s appearances. She had set her heart on a nose that would be ‘tip-tilted like a flower’, an idea she’d got partly from her younger sister’s pretty nose and partly from reading Tennyson’s Idylls of the King:

Lightly was her slender noseTip-tilted like the petal of a flower.

Unfortunately the surgeon, though he was able to offer her a choice of noses from a selection of plaster models, wasn’t up to the job. After working on his patient for some time he stopped. Peggy was only under local anaesthetic, which wasn’t enough to prevent her from suffering great pain, so when the surgeon told her he was unable to give her the nose she’d chosen after all, she told him to stop, patch up what he’d done, and leave things as they were.

According to Peggy, the result was worse than the original, but to judge by the photographs taken of her in Paris by Man Ray only four years later, the nose is not as offensive as she makes it sound, though in the years which followed it coarsened, and she was careful to avoid being photographed in profile. She made light of the whole experience, which was brave of her, given that she also tells us that her new nose behaved like a barometer, swelling up and glowing at the approach of bad weather. It is hard to judge from ‘before’ and ‘after’ pictures whether the surgeon actually altered her nose all that much. Its shape was inherited by her son Sindbad. One person who knew her well in later life wonders if the whole story of the nose job wasn’t an invention, but this seems unlikely. Peggy was obsessed with the shape of her nose, and with the idea that because of it she was ugly. It has been said that she was still thinking of having a fresh operation late in life, though her nose never impeded her sex life (something which was extremely important to her); and by the 1950s, when cosmetic surgery was much safer and more predictable, she had moved on emotionally and psychologically from serious concern about such things.

People were cruel about Peggy’s nose throughout her life. In the thirties Nigel Henderson, the son of her friend Wyn, said that she reminded him of W.C. Fields, and the same resemblance was called to mind by Gore Vidal decades later. The painter Theodoros Stamos said, ‘She didn’t have a nose – she had an eggplant,’ and the artist Charles Seliger, full of sympathy and regard for Peggy, remembered that when he met her in the 1940s her nose was red, sore-looking and sunburnt: ‘You could hardly imagine anyone wanting to go to bed with her, to put it cruelly.’ Peggy’s heavy drinking during the 1920s, thirties and early forties didn’t help. And however much she made light of what she regarded as an impediment, there is no doubt that the shape of her nose reinforced her low self-esteem.

Notwithstanding his failure, the surgeon relieved her of about $1000 for the operation. Bored and in need of consolation, Peggy took a friend to French Lick, Indiana, and proceeded to gamble away another $1000 before returning to New York, still with little or no idea of what to do with herself, though some of the seeds Lucile Kohn had planted were showing signs of sprouting. Margaret C. Anderson, founder-editor of the then six-year-old Little Review, perhaps prompted by Kohn, approached her for money and an introduction to one of her moneyed uncles. Peggy didn’t help with cash, but sent Anderson off to Jefferson Seligman, in the hope that even if she didn’t get the $500 she sought, she might at least get a coat out of the uncle.

The Little Review was one of the most important and long-lived of the literary and arts magazines that flourished in the first half of the twentieth century, before most of them were superseded by television. It moved home in the course of its fifteen-year life from Chicago to San Francisco, thence to New York, and finally to Paris, publishing many of the great names of contemporary literature, including T.S. Eliot, W.B. Yeats, William Carlos Williams, Ford Madox Ford and Amy Lowell. Ezra Pound was its foreign editor from 1917 to 1919, and its major claim to fame was its serialisation, beginning in 1918, of James Joyce’s Ulysses. It may seem odd that Peggy was not keener to associate herself with a review which was concerned with so many of the people and ideas she was soon to embrace; but it wasn’t long before she became involved, albeit tangentially, with the literary world.

Needing above all to work, and to meet people outside her immediate social circle, Peggy took a job with her own dentist as a temporary nurse-cum-receptionist, filling in for the regular girl who was off sick. The work came to an end when the proper nurse returned, much to Florette’s relief; she hadn’t liked the idea of her friends and acquaintances discovering that one of her daughters was working as a dental nurse. Florette’s relief was, however, short-lived. Peggy now took a much more significant, though unpaid, job, as a clerk in an avant-garde bookshop, the Sunwise Turn, not far from home, in the Yale Club Building on 44th Street. The bookshop was run by Madge Jenison and Mary Mowbray Clarke. Clarke was the dominant partner, and ran the store as a kind of club. She only sold books she believed in, and literati and artists were constantly dropping in and staying to talk. Peggy quickly found that here was a society to which she wanted to belong.

She’d got the job through her cousin Harold Loeb, seven years her senior, who had injected $5000 into the Sunwise Turn when it ran into financial difficulties, and was now a partner in the enterprise. Harold was the son of Peggy’s aunt Rose Guggenheim and her first husband, Albert Loeb, whose brother James was the founder of the Loeb Classical Library.

Harold inherited a strong literary inclination. He joined the great exodus of young Americans to Europe in the early 1920s, published three novels and an autobiography, and founded and ran, first from Rome and then from Berlin, a short-lived but immensely important arts and literature magazine called Broom, which published, inter alia, the works of Sherwood Anderson, Malcolm Cowley, Hart Crane, John Dos Passos and Gertrude Stein. Aimed at an American readership, Broom also ran reproductions of works by such artists as Grosz, Kandinsky, Klee, Matisse and Picasso, all then little-known in the New World, and many of whom were still struggling for recognition in the Old. It was always a struggle to keep Broom afloat, and at the outset Harold appealed to his uncle Simon for funds. This may not have been tactful. Harold belonged to another ‘poor’ Guggenheim branch – his mother had been left only $500,000 by her father. Uncle Simon had given him a well-paid job with the family concern as soon as he graduated from Princeton, but a life in business had not suited Harold at all and he had left to become, to all intents and purposes, a bohemian. His request was frostily rejected: ‘I have since discussed with all your uncles the question of the endowment you wished for Broom, and I am reluctantly obliged to inform you we decided we would not care to make you any advances whatsoever. Our feeling is that Broom is essentially a magazine for a rich man with a hobby … I am sorry that you are not in an enterprise that would show a profit at an earlier date.’

Harold had already left for Europe, where his uncle’s letter reached him. He replied sharply: ‘From what little I know of your early career, it seems to me that you have more than once chosen the daring and visionary to the safety-first alternative …’ He did not get a reply.

The biographer Matthew Josephson was an associate editor of Broom as a young man, and a recollection in his memoirs provides an interesting footnote to this contretemps:

The curious thing about this episode is that a while later those same hard-boiled Guggenheim uncles of his wound up by imitating their poor relation Harold Loeb, and becoming patrons of the arts on a gigantic scale. Beginning in 1924, Uncle Simon donated some $18 million to the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation [named for one of his sons who had died of pneumonia in 1922 aged seventeen] which provided fellowships for hundreds of artists and writers, including quite a number of contributors to Broom whom Simon Guggenheim had formerly been unable to understand.

Broom ceased publication in 1924, and it was then that Harold went to Paris to work on his first novel. There he met the young Ernest Hemingway. Hemingway had had a few stories and poems published, but was still feeling his way as a writer. He was ambitious and insecure. What started as a friendship developed into rivalry and ended in unpleasant schism.

The bottom line is that Hemingway was envious of Loeb, who was both better educated and richer than he was. Loeb could and did outbox the boastful Hemingway, and he was a better tennis player. He also had more success with women, and at the time it looked as if he would outstrip Hemingway as a writer. When a party was made up to go to the running of the bulls in Pamplona, which Hemingway had attended before, and on which he held himself to be an expert, Loeb actually grappled a bull, was lifted aloft as he gripped the animal’s horns, then managed to disengage successfully, landing on his feet, eyeglasses still securely on his nose. The crowd roared their approval.

Hemingway, whose association with bulls was limited to talking about them and watching them die (something Loeb found distasteful), couldn’t forgive the perceived humiliation – the more so since Harold was making headway with Lady Duff Twysden, whom Hemingway had also hoped to impress.

Loeb did not set out to needle Hemingway, but the younger man’s resentment ran deep, and spilled out in his first novel, The Sun Also Rises (1926), in which a number of those present on the Pamplona trip in the summer of 1925 are cruelly portrayed; but none more so than Loeb, who appears in the book as Robert Cohn. Written in hot blood – Hemingway finished the novel in late September 1925 – The Sun Also Rises appears today so anti-Semitic (even when one allows for a period when anti-Semitism was, in certain circles, semi-acceptable) as to beggar belief. The real focus for Hemingway’s hatred of Cohn lies in the fact that he was in all ways bested by Loeb. Loeb rose above it, but never in his long life (he died in 1974) got over the betrayal.

The extent to which Hemingway caused offence is best described by Matthew Josephson:

After The Sun Also Rises came out, Harold said no more about Hemingway. Their friendship was ruptured. It seemed that in completing his story of the so-called ‘Lost Generation’, the young novelist had painted his circle of friends in Paris from life … there were at least six of [the novel’s] characters who recognised themselves in its pages and set off in search of the author in order to settle accounts with him, according to the reminiscences of James Charters [Jimmie the Barman], a retired English pugilist who was Hemingway’s favorite barman in Paris …

I had paused for a moment at the bar of the Dôme for an apéritif, and stood beside a tall slender woman who was also having something and who engaged me in conversation, at once informed and reserved. She had a rather long face, auburn hair, and wore an old green felt hat that came down over her eyes; moreover, she was dressed in tweeds and talked with an English accent. We were soon joined by a handsome but tired-looking Englishman whom she called ‘Mike’, evidently her companion. They drank steadily, chatted with me, and then asked me to go along with them to Jimmy’s Bar near the Place de l’Odéon, a place that had acquired some fame during my absence from France. In a relaxed way we carried on a light conversation, having three or four drinks and feeling ourselves all the more charming for that. Then Laurence Vail came into the bar and hailed the lady as ‘Duff’. At this, I began to recall having heard about certain people in Paris who were supposed to be the models of Hemingway’s ‘lost ones’; the very accent of their speech, the way they downed a drink (‘Drink-up-cheerio’), and the bantering manner with its undertone of depression. It was all there.