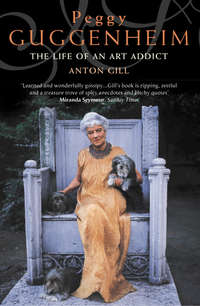

Peggy Guggenheim: The Life of an Art Addict

Peggy accepted this new proposal, but decided only to buy a hat, not a new outfit, for the ceremony, just in case there was another hitch; and there was what looked like a final hiccup when Gertrude rang Peggy on the morning of the wedding to tell her, ‘He’s off.’ Peggy took this to mean that Laurence had done a bunk, but his mother only meant that he was on his way.

The civil ceremony took place at the town hall of the sixteenth arrondissement on 10 March 1922. Later there was a party at the Plaza-Athénée, attended by a mixed bag from four different backgrounds: Florette invited a phalanx of Seligman cousins and friends from the Right Bank; Gertrude asked members of her set, the old-established American community; Peggy asked her new friends, mainly drawn from the circle of suitors she had established with Fira Benenson – one of whom, Boris Dembo, wept at the thought that he was not marrying Peggy himself; Laurence’s guests were a motley band of poor expatriate American writers and artists along with his French friends.

After a champagne reception at the Plaza, the party moved on, collecting all manner of people as it passed various bars on the way to the Boeuf-sur-le-Toît and Prunier’s. The next morning Peggy, the worse for wear, was visited by Proust’s doctor, who gave her a ’flu injection.

She awoke to find herself disappointed in marriage. Her disaffection was reinforced at lunch with her mother. Florette asked loudly about the finer points of the wedding night, drawing attention to the smell of Lysol Peggy had about her, making the waiters prick up their ears. This caused Peggy some embarrassment, but Florette approved of her daughter’s inherited belief in the curative and disinfectant properties of Lysol, especially in getting rid of the nasty smells and risks of infection that sex involved.

Before the honeymoon, Florette brought Peggy a passport in her new name. As a married woman, Peggy was now on Laurence’s passport, but with this independent one she could run away if Laurence became too much for her. This action of Florette’s may have been prompted by Peggy herself, since Laurence had already, even before the wedding, begun to show a less attractive side. When drunk, which he often was, he could become violent. He would make scenes in restaurants, smash bottles, wreck furniture in hotel rooms and attack Peggy physically. The worst of this was yet to come. Although there is no excuse for Laurence’s extravagant behaviour, Peggy sometimes consciously taunted him into it, knowing exactly how to provoke an angry reaction. It was one way of satirising the male dominance she instinctively despised, and she deployed it often in her life, despite the violence she brought on herself. At this stage, however, no one could have accused Peggy of not indulging him. He was so depressed at the thought of being separated from Clotilde that Peggy suggested his sister should join them in Capri, where they were to spend most of their honeymoon. But when Peggy also suggested that she bring along her Russian teacher, Jacques Schiffrin, Laurence refused.

En route to Capri, the newlyweds stopped in Rome, where Peggy’s cousin Harold Loeb was running his magazine Broom. Laurence had already published one or two pieces in it, and Harold now asked him for a poem. Laurence had already taken against the Guggenheim family, specifically the brothers who controlled the family firm, and was to remark that he would happily throw them all over a cliff. His dislike was probably prompted by the fact that Peggy’s capital was carefully protected; but it found an outlet in the poem he submitted:

Old men and little birdsToo early in the morningMake squeaks.

Little birds are more brazen;Primly, they dip their feet in puddles.Old men have delicate feet.

Old men have delicate bowels,Little birds are careless,Near love of neitherIs sweet.

Little birds chirp, chirp, chirp, chirup;Old men tell stories, tell stories;Both die too late.

When the piece appeared in the September 1922 edition of Broom, it provoked a querulous reaction from Peggy’s cousin Edmond. Loeb calmed him down, but Laurence felt a flicker of grim satisfaction.

Peggy and Laurence, bare-legged and besandaled to underline their contempt for anything bourgeois, proceeded on their expensive honeymoon. Privately, Peggy continued to nurse her sexual and personal disaffection with marriage; but at least getting married had achieved one goal for both of them: independence from their families.

Capri in the early 1920s was a beautiful and still isolated place, a resort for the rich and the eccentric. Here a young French nobleman consorted with the goatherd he had adopted as his boyfriend, had educated, and introduced to opium; here lived the German industrialist Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach in a magnificent mansion; and here too, more modestly, lived the Compton Mackenzies. An old lady, reputed to have been the lover of a former Queen of Sweden, sold coral in the streets; and during the season before Peggy’s arrival Luisa Casati, an exotic figure who became the mistress of the poet, womaniser and war hero Gabriele d’Annunzio, had wandered the island in the company of a pet leopard. Casati owned a palace in Venice, the Palazzo Venier dei Leoni, which thirty years later would become Peggy’s final home.

Despite the exotic nature of the place, Peggy didn’t enjoy it much, since her style was cramped by the presence of Clotilde. If Laurence’s mother had accepted Peggy – though Peggy was never allowed to address her as anything other than ‘Mrs Vail’ – Clotilde was not going to relinquish one iota of her hold over her brother. It was humiliating to be treated as the unwelcome third person on one’s own honeymoon, and as Peggy put it, ‘[Clotilde] always made me feel that I had stepped by mistake into a room that had long since been occupied by another tenant, and that I should either hide in a corner or back out politely.’ Peggy also, despite her own ambitions in that direction, found her sister-in-law’s libertinage shocking. She was also envious of it. To make matters worse, Clotilde’s lovers drove Laurence into a jealous frenzy. Clotilde was three or four years older than Peggy, more attractive and more worldly. She delighted in making Peggy feel inferior, but resented Peggy’s wealth. Peggy quickly came to realise what a weapon her money was.

She had enough obduracy not to let herself be undermined by the Vails’ snobbery and anti-Semitism. At the end of the summer they left Capri, travelling to St Moritz via Arezzo, San Sepolcro, Venice, Florence and Milan. By then the two sisters-in-law seem to have come to some kind of accommodation. Laurence and Peggy played tennis together so well that they won a tournament, and they seemed, if not passionately in love, at least genuinely fond of one another. Nevertheless, when the autumn came, Peggy left for New York for a long-arranged visit to Benita, while Laurence took Clotilde off on a tour of the Pays-Basque on a motorbike which Benita had given him as a wedding present.

In New York, Peggy arranged for the publication of Laurence’s short work Piri and I, and had an enjoyable time with her sister despite the jealousy she still felt for Benita’s husband.

Before she returned to Europe and her own husband, she discovered that she was pregnant.

CHAPTER 8 Laurence, Motherhood and ‘Bohemia’

At the end of 1922 Peggy returned to Europe with her Aunt Irene. Laurence was at Southampton to meet the ship. The couple were delighted to see one another again, and Laurence behaved himself right through a visit to Peggy’s cousin Eleanor in Sussex, where she lived with her cattle-farmer husband, the Earl Castle Stewart. But the Vails were an ill-matched pair, and no sooner were they back in Paris than they began to quarrel. Laurence had boundless energy and great, if misused, intelligence. He would invite anyone he met on the street, including whores and clochards, to parties, he would spend up to three days on binges, and he was deeply frustrated by Peggy’s apparently placid nature.

Peggy, however, knew exactly how to provoke him, and frequently did so. She was still in touch with her former teacher Jacques Schiffrin, and had advanced him money to help set up his imprint Les éditions de la Pléiade. When she told Laurence she was in love with Schiffrin he went berserk, smashing an inkpot and the telephone in their suite in the Hôtel Lutétia, where they were living. The splattered ink ruined the wallpaper, which had to be replaced, and Peggy had to engage a man to remove ink from the carpets and floors, which took weeks. There is nevertheless a hint of enjoyment in Peggy’s recounting of the story, as if this were all part and parcel of the anarchic, artistic life she believed she was living. And she retaliated in a way which was calculated to stir up Laurence further, by reminding him that it was she who held the purse-strings. Through that she controlled the relationship. Laurence was too weak to break free, and revenged himself for his humiliation by harping on Peggy’s lack of finesse, education and sophistication. In fact Peggy, a natural autodidact, was continuing to educate herself through the artists and writers she came into contact with, though it was a slow process, and her real relationship with the artistic life of Paris was not to come until much later.

Peggy had an acute perception of both the situation and her husband’s character:

Laurence was very violent and he liked to show off. He was an exhibitionist, so that most of his scenes were made in public. He also enjoyed breaking up everything in the house. He particularly liked throwing my shoes out of the window, breaking crockery and smashing mirrors and attacking chandeliers. Fights went on for hours, sometimes days, once even for two weeks. I should have fought back. He wanted me to, but all I did was weep. That annoyed him more than anything. When our fights worked up to a grand finale he would rub jam in my hair. But what I hated most was being knocked down in the streets, or having things thrown in restaurants. Once he held me down under water in the bathtub until I felt I was going to drown. I am sure I was very irritating but Laurence was used to making scenes, and he had had Clotilde as an audience for years. She always reacted immediately if there was going to be a fight. She got nervous and frightened, and that was what Laurence wanted. Someone should have told him not to be such an ass. Djuna tried it once in Weber’s restaurant and it worked like magic. He immediately renounced the grand act he was about to put on.

These tantrums often got Laurence into trouble with the police, but it was a mania that stayed with him for most of his life. In 1951 he got into a row in the dining room of the Hotel Continental in Milan with a friend of Peggy, Carla Mazzoli. As Maurice Cardiff, who knew Peggy and was there at the time, remembers: ‘When he had worked himself into what seemed a simulated rather than genuine frenzy, he left the table to return with a pot of jam he had taken from the restaurant kitchen. Dipping his finger into the pot he tried, unsuccessfully, for we all intervened, to rub the jam into Carla’s hair.’

Ample reasons for his pique at Peggy’s behaviour can be found in Laurence’s novel Murder! Murder!. Written in the closing years of the marriage, it is an account of the near-hysterical relationship between its protagonists, Martin Asp and his wife Polly (in Vail’s unpublished memoir Here Goes, Peggy appears under the equally thin guise of Pidgeon Peggenheim). Even allowing for the prevalent anti-Semitism of the time, the novel is particularly unpleasant about the Jews, and though at its most extravagant it shows the influence of Lautréamont’s Maldoror, the 1868 novel which had such a profound effect on the Surrealists, and describes a man possessed of a singularly nasty imagination, it nevertheless also displays a rather dutiful attempt to ‘horrify the bourgeoisie’. But while the book is honest, and skilfully exposes some of Peggy’s less attractive traits, such as an obsession with the details of petty spending, and an obstinate, ingrained selfishness, a huge resentment is apparent. Laurence (in the character of Martin Asp) describes how his sleeping wife’s lips ‘move as she dreams of sums’, and says ‘it makes her nervous to follow one train of thought for any length of time. She goes in for action. She tries to reckon out how much money she has spent on tips since the first of June.’

In their own recollections, each partner paints the other in darker colours than they deserve, but one longer passage from the novel can be quoted without comment (except to express the hope that some of it is meant ironically) to complement that quoted above from Peggy’s autobiography:

Suddenly, even while I speak and drink, my brain expands, parts, opens. It will be a great thing, the great thing I shall do – a very great thing. A little later, when I am kindly drunk, I shall, magnanimously, fundamentally, make it up with my young wife. It will be a great thing – this making up. For we have been quarrelling for nearly fifty hours.

Forty-six hours ago I had been reading one of my poems to a friend. Now it is not often that I thus hazard friendship. On this occasion, however, the friend had particularly insisted. Three times I met his odd request with fairly firm refusals. The fourth, I weakened. Too much false modesty, I argued, is bad for the morale; I may suddenly feel modest. And why not, just this once, give myself a treat? Besides, my friend might not ask a fifth time.

And now to Poll. Since Sunday noon she had been reading a novel of Dostoyevsky. She had read 114 pages on Saturday, 148 on Sunday, 124 on Monday, on this day, Tuesday, 96. Still the night was young. She was in form. She might still break her record.

Meanwhile, disrespectful of these facts, I settled myself in my chair, happily began reciting:

Some who believe in GodTake pills.

Some patient womenLean perhaps with stout hopePerhaps behind their hungry featuresHopeless …

It was at this moment that I became aware of a loud continuous whisper. I glanced up. Polly was leaning over her book, her lips were moving. My recital, it was evident, interfered with her concentration; still, by murmuring the words quite loud, she could manage not to hear me. She still hoped, if not to achieve a record, to equal her daily average of 130 pages.

Abruptly, I stopped reciting. My silence, I thought, will certainly move her to repentance and confusion. I was mistaken. Now, unimpeded by my own gloating voice, I could hear the words of the immortal Russian …

Suddenly I lost my temper. Then, with sarcasm:

‘Sorry, if I disturbed you.’

She glanced up with bright friendly eyes: ‘Oh not at all. Do go on with your poetry.’

My friend laughed lightly. ‘Don’t you like Martin’s poem?’

‘A lot. But, you see, I’ve heard it once already.’

I bit my tongue. ‘My mistake. I thought you could stand a second reading.’

‘Go on,’ said my friend. ‘Let’s hear the rest of it.’

I shook my head. Who was I, after all, to compete with Dostoyevsky? … My temper rose. Carefully tearing my manuscript in two parts, I turned my back on both friend and wife, concealed the fragments in my pocket.

When finally after ten minutes my friend left, I gave vent to my indignation:

‘You should have married a Wall Street broker. Or a Russian taxi-driver.’

I continued in this strain for upwards of two hours, including in my torrent of reproach my wife, her mother, her sisters, her cousins, her aunts, her uncles, in short, a considerable part of the Jewish people. Still, had she at any time during this period knelt or wept, I would, eventually, have vouchsafed her my forgiveness. Not once, however, did she show the slightest sign of ardent love, of deep, complete repentance. Several times, probably noting I was embarked on a symphony of abuse whose themes to develop must take at least some minutes, her eyes would quickly stray towards ‘The Brothers Karamazov’. Once, having turned my back, I heard, or thought to hear, the dry sound that a page makes when a hand turns it over.

In the meantime, though Peggy does make one reference in her memoirs to anxiety on its behalf, their child crouched in the womb, its welfare largely unheeded.

In the meantime, too, Laurence carried on his role as King of Bohemia, largely by virtue of having enough money to throw parties, and through him Peggy immersed herself more and more in the expatriate cultural life of Paris. The waves of newcomers continued unabated as the 1920s progressed. Matthew Josephson, who had returned to New York after the collapse of Broom in 1923, but, disliking the respectable Wall Street job he had taken, went back to Paris with his wife in 1927, was struck by the speed of the change wrought upon the Left Bank by the new influx of Americans: ‘Our ship alone had brought 531 American tourists in cabin class … There were certain quarters of Paris that summer where one heard nothing but English, spoken with an American accent … The barmen [were] mixing powerful cocktails, dry martinis, such as one never saw there in 1921 or 1922.’ Away from Prohibition, Americans relaxed. Everybody drank. Most people drank too much at one time or another. Drinking was part of the culture, and one regret was that the French authorities had banned the sale of true absinthe, the ruling drink of the 1890s. True absinthe has a spirit base in which the flowers and leaves of wormwood are instilled, together with star anise, hyssop, angelica, mint and cinnamon. Dull green in colour, the toxic qualities of absinthe led to its proscription: it had a percentage proof of between fifty and eighty-five. John Glassco, who managed to get hold of some in Luxemburg, left a vivid reminiscence of its effect:

The clean sharp taste was so far superior to the sickly liquorice flavour of legal French Pernod that I understood the still-rankling fury of the French at having that miserable drink substituted for the real thing in the interest of public morality. The effect also was as gentle and insidious as a drug: in five minutes the world was bathed in a fine emotional haze unlike anything resulting from other forms of alcohol. La sorcière glauque, I thought, savouring the ninetyish phrase with real understanding for the first time.

By 1928, Scott Fitzgerald could write that Paris ‘had grown suffocating. With each new shipment of Americans spewed up by the boom the quality fell off, until towards the end there was something sinister about the crazy boulevards.’ The Dôme, which had been the social centre and bush-telegraph office, the place you went to find a job or a place to stay, became so swamped by Americans that ‘real’ artists moved down the road to the Closerie des Lilas, where Hemingway sat and wrote. A literary crowd centred on the Hôtel Jacob; its numbers included Djuna Barnes, Sherwood Anderson, Edna St Vincent Millay and Edmund Wilson. The photographer Man Ray and his mistress, the model Kiki (Alice Prin), who wore extraordinary make-up designed by him, also formed part of the circle: ‘Her maquillage,’ wrote Glassco of Kiki, ‘was a work of art in itself: her eyebrows were completely shaved and replaced by delicate curling lines shaped like the accent on a Spanish “n”, her eyelashes were tipped with at least a teaspoonful of mascara, and her mouth, painted a deep scarlet that emphasized the sly erotic humour of its contours, blazed against the plaster-white of her cheeks on which a single beauty-spot was placed, with consummate art, just under one eye.’

Peggy was not the only member of the American artistic circle in Paris who was not herself an artist; many others used their money to encourage and subsidise creative but impecunious talents. Though hardly a champion of the avant-garde – she favoured the arts of the belle époque – Natalie Clifford Barney had inherited $3.5 million from her father and in 1909, when she was thirty-three, bought number 20, rue Jacob, a vast seventeenth-century mansion in which she lived very stylishly for the next half-century. As an early arrival she, like Gertrude Stein, was able to make contacts within the French cultural arena, though her house became a specialised centre for lesbian culture – Natalie had known she was a lesbian since the age of twelve, and she is the original for Valerie Seymour in Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness, published in 1928. Thrifty like Peggy, she was also a benefactress to Djuna Barnes, though unlike Peggy, she never supplied the novelist with a regular stipend.

Mary Reynolds, one of the circle’s most striking members, was the widow of Matthew Reynolds, killed in 1918 while fighting in France with the US 33rd Infantry Division. She moved to Paris to escape pressure at home to remarry. Her group of friends included Cocteau, Brancusi and the American author and journalist Janet Flanner, who wrote the New Yorker’s ‘Paris Letter’.

Later in the decade the heiress Nancy Cunard founded The Hours Press, which she ran between 1927 and 1931; she was the first person to publish the young Samuel Beckett: Whoroscope appeared in 1930, in a hand-set edition of one hundred, followed by a second edition of two hundred. She also published, among others, Robert Graves, Ezra Pound and Laura Riding. Nancy had acquired her first printing press from William Bird, who ran the Three Mountains Press on the Île St Louis.

Perhaps the Left Bank’s most famous artistic haven was the bookshop Shakespeare and Co., at 12 rue de l’Odéon (it has since moved to rue de la Bûcherie), founded by Sylvia Beach, the daughter of a minister from Princeton, New Jersey, in 1919. In this literary Mecca could often be found Allen Tate, Ezra Pound, Thornton Wilder, Hemingway and, on occasion, the great literary lion of the expatriate community, James Joyce.

It was at the bookshop that Robert McAlmon founded his Contact Editions Press in the early 1920s, the title deriving from William Carlos Williams’ mimeographed poetry magazine, Contact. Early in 1921, in New York, McAlmon married the English novelist ‘Bryher’ – the nom-de-plume (taken from the name of one of the Scilly Isles) of Winifred, the daughter of the vastly wealthy English shipping magnate Sir John Ellerman. McAlmon said he was unaware of Winifred’s true identity (and therefore of her money) until after they were married, but this seems unlikely, since it was from the first a marriage of convenience: both parties were homosexual, but in those days Bryher needed the cover of marriage in order to be able to travel freely and to adopt when necessary a respectable place in society (according to Matthew Josephson she was at odds with her family, though McAlmon was received by her father in London). By marrying, she also made herself eligible to inherit a fortune. The couple scarcely lived together; Bryher was a friend of the Sitwells, and was already involved in a long-term relationship with the more considerable poet and novelist ‘HD’, Hilda Doolittle, a native of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, who had followed her friend Ezra Pound to Europe in 1911.

While his wife travelled, McAlmon stayed in Paris, drinking too much and indulging in some minor writing and a memoir, later revived by his friend Kay Boyle, of his life and of the artistic life of the time.

McAlmon was a fine editor, with a well-developed sense of what was best in the new writing, and used the money he derived as an ‘income’ from his marriage to set up his small publishing house. Despite personal differences between the two men (McAlmon could be very bitter), he was the first to publish Hemingway, and he also produced volumes of verse by William Carlos Williams, Mina Loy and Marsden Hartley. Though he had dreaded the thought of being destitute once Bryher – as she inevitably did, after about six years – divorced him, he found himself in fact with a handsome settlement of about £14,000, which led his friends Bill Williams and Allan Ross Mcdougall to dub him ‘Robert McAlimony’.