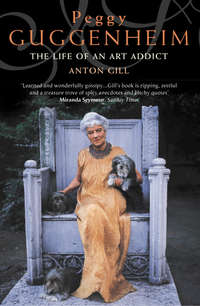

Peggy Guggenheim: The Life of an Art Addict

The war had shaken many beliefs to the core. No longer could anyone say that ‘history is bunk’, or get away with a blind belief in scientific progress. The flower of young European manhood had been killed off. There was a surge of interest in mysticism. Theosophy, which leant towards Buddhism in an attempt to synthesise man’s aspirations with the greater forces of nature and the supreme being, and theories of universal brotherhood, already promoted in the nineteenth century by Helen Blavatsky and later on by Annie Besant and Sir Francis Younghusband, was much in vogue. Brancusi, Kandinsky and Mondrian were all Theosophists; there were few practising Christians among the modern artists. Besant declared the Indian Jiddu Krishnamurti to be the new saviour, and for a time he enjoyed a huge following. Charlatans like Ivan Gurdjieff and Raymond Duncan (the brother of Isadora) flourished as the idea of communes and a return to the simple life took root. Spiritualism became such a vogue in the United States that Harry Houdini made a second career out of exposing fake mediums. The Dadaist movement, born in Zürich during the war, mocked and questioned everything, but the old order was its particular target. There were other potent influences. The Communist revolution had taken place in Russia, and in 1913 Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams, which was to have such an influence on the Surrealists, appeared in an English translation.

The term ‘lost generation’, which was applied to the young post-war American émigrés in Europe, to whom Peggy was soon to attach herself, derives from a disparaging remark Gertrude Stein made to Hemingway when he and the painter André Masson and the poet Evan Shipman arrived late and drunk at one of her salons. As Masson and Shipman later related the story to Matthew Josephson, Stein had said, ‘Vous êtes tous une génération fichue.’ Stein got the expression from her garage mechanic, who used it to describe his apprentices.

Stein had arrived way ahead of the post-war émigrés, and as a patron of painters she quickly established friendships with many of them, notably Picasso, Matisse, Masson, Picabia, Cocteau and Duchamp. Among the other pre-war arrivals in Europe were the poets Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, Hilda Doolittle (‘HD’) and Robert Frost. In England Eliot integrated completely and later became naturalised, but few of the others cut their links with their home country. The Americans who arrived en masse after the war stuck together. The Right Bank crowd was led by F. Scott Fitzgerald, while the Left Bank attracted the poorer artists and writers. By all logic Peggy should have belonged to the former group, but luckily for her, fate was to decree otherwise. There were two other American groups: the old-established rich patrician community, to which Laurence Vail’s mother belonged, and the casual tourists who quickly filled all the restaurants that got into the guide books.

In the forefront of the artistic post-war immigrants were John Dos Passos, E.E. Cummings (later ‘e.e. cummings’) and Hemingway, all three of whom had worked as volunteer ambulancemen during the war. Ambulancemen enjoyed greater freedom of movement than regular soldiers, and had more contact with local people. Dos Passos did make contact with French writers, though Cummings, despite his fluent French, did not. The writer and critic Malcolm Cowley, alone in Montpellier writing a thesis on Racine, also managed to bridge the gap, as did Matthew Josephson, who became friendly with a broad group of writers and artists including Jules Romains, Tristan Tzara and Louis Aragon. There was some reciprocation: Aragon and his friend the poet Philippe Soupault both read English, adored America, read all the ‘Nick Carter’ dime novels they could find, and were committed fans of Charlie Chaplin.

The quiet streets and dim bars recorded by the pioneer photographer Eugène Atget before the war were giving way to noisy thoroughfares and brassy cafeterias. Workers’ cafés, such as the Dôme, quickly became the stylish haunts of young American drinkers; but the charm of the old Paris didn’t disappear overnight. John Glassco, who lived in the rue Broca district, wrote that ‘in the rue de la Glacière I met a man with a flock of goats, playing a little pipe to announce that he was selling ewe’s milk from the udder.’ And in A Moveable Feast Hemingway recalled a similar scene when he was living in the rue Cardinal Lemoine in 1921: ‘The goatherd came up the street blowing his pipes and a woman who lived on the floor above us came out onto the sidewalk with a big pot. The goatherd chose one of the heavy-bagged, black milk-goats and milked her into the pot while his dog pushed the others onto the sidewalk.’ In The Sun Also Rises Hemingway lamented how things had changed four years later: ‘We ate dinner at Mme Lecomte’s restaurant on the far side of the island. It was crowded with Americans and we had to stand up and wait for a place. Someone had put it in the American Women’s Club list as a quaint restaurant on the Paris quais as yet untouched by Americans, so we had to wait forty-five minutes for a table.’ Elsewhere in A Moveable Feast he records poignantly that the old waiters at the Closerie des Lilas, Jean and André, had been forced to shave off their drooping moustaches and don white ‘American’ jackets to serve their new clientele. With flashy new establishments like the Coupole opening only a few hundred metres away along the boulevard du Montparnasse, and Americans flocking to the Sélect and the Rotonde, something had to be done to smarten up the Lilas’ image.

Up on the boulevard St Germain the Flore and the Deux Magots are still there, side by side, dispensing expensive but good cognac to Frenchman and tourist alike, the Magots just having an edge over the dingier Flore; but many of the other bars Peggy was soon to be frequenting around what is now the Place Pablo Picasso, the junction of the boulevard du Montparnasse and the boulevard Raspail, have either disappeared or changed beyond recognition. The Dôme is an expensive fish restaurant, though its bar is still there. The Sélect and the Rotonde still have a slightly seedy charm, while La Coupole is as grand a piece of art déco as ever it was. The Falstaff is now a cheap restaurant, and the Jockey and the Dingo have disappeared.

In the 1920s, though, this was the centre of ‘Bohemia’ for the American expatriates in Paris, and it was waiting to be introduced to Peggy.

Leon and Helen Fleischman had taken up with Laurence Vail, now back in Paris, and through them he met Peggy again. Laurence was an original. He looks bad-tempered and intense in photographs, though those who knew him well were fond of him, and many think that as an artist he sold himself short. By modern standards he looks physically weak, though he was an expert skier and alpinist. By the standards of the day he wore his blond hair long, and he avoided hats. He dressed extravagantly, buying curtain or furniture material in Liberty prints to be made into shirts, with yellow or blue canvas or corduroy trousers, and white overcoats, or jackets all the colours of the rainbow. As he was pigeon-toed he preferred sandals to shoes, but made a great fuss over buying any kind of footwear, to the extent that Peggy suspected him of having a mild complex.

Vail was a handsome man, despite a beaky, aquiline nose, with a volatile and childish personality which overshadowed his better points. Seven years Peggy’s senior, he had been born in Paris. His mother, Gertrude Mauran, came from a wealthy New England family, and was every inch a Daughter of the American Revolution. His father, Eugene, was the product of a New York father and a Breton mother, and a moderately successful landscape painter (particularly of Venice and Brittany) by profession.

From his mother Laurence had inherited a love of the mountains. She was one of the first women ever to climb Mont Blanc, and had encouraged her son to be a mountaineer from an early age. From his father he inherited the less attractive traits of advanced neurosis, and an egotism which manifested itself in temper tantrums when he thought he was not the centre of attention. Eugene Vail was also a hypochondriac with a strong suicidal tendency. It was from his father that Laurence inherited his artistic sensibility, and a sense of humour which never had enough of a chance to show itself. And if Peggy’s family had its share of eccentrics, mention should be made here of Laurence’s Uncle George, Eugene’s brother. George was a great aficionado of roller-skating. Roller-skates had been around for over a hundred years, but with the introduction of the ball-bearing in the 1890s their efficiency was much improved, and it was possible to go very much faster on them. George added to his speed by holding on to the backs of lorries, and thus it was that he would meet his end, when in his sixties. He was also a great lover, and made an album collection of his mistresses’ pubic hairs.

Neither parent – Gertrude cold and domineering, and Eugene self-obsessed – had much time for Laurence or his younger sister Clotilde, and the children in consequence were drawn close together. Though suggestions of incest are without foundation, their relationship did inspire William Carlos Williams’ 1928 novel A Voyage to Pagany, in which an American doctor and writer, Evans, returns to Paris to see his sister, who is pursuing a career as a singer (Clotilde had a brief career as an actress and opera singer herself).

… differing [physically] as the brother and sister did, they had grown up intimately together, almost as one child. They had shared everything with each other … The thing which had always kept them together was the total lack of constraint they felt in each other’s company – a confidence which had never, so far, been equally shared by them with anyone else.

Elsewhere in the book, a minor character called Jack Murry, a writer, is given a description based on Laurence:

The firm, thin-lipped lower face, jaw slightly thrust out, the cold blue eyes, the long downward-pointing, slightly-hooked straight nose, the lithe, straight athletic build … [Evans] loved his younger friend for the bold style of his look at life. Often, when Jack demolished situations and people with one bark, Evans smiled to himself at the rudeness of it, the ruthlessness with which so much good had been mowed down.

Both Eugene and Gertrude had private money, though Gertrude, with an income of $10,000 a year, was considerably the richer of the two. From this she paid her husband’s hospital and medical consultancy bills (he had already run through his own patrimony on such things), and gave Laurence a small allowance of about $1200 a year – just enough to live on without working, and enough to make him rich in comparison with the artists with whom he associated. This, coupled with a great love of the bottle, was the main reason why Laurence never exploited to the full what artistic talents he had. On the other hand, a streak of humorous self-awareness runs through his own writings and recorded pronouncements. ‘I take my medicine;’ he writes in his autobiographical novel Murder! Murder!, ‘gulp down without a murmur a tumbler of imported New York whiskey. My stomach sinks, bravely reacts. And suddenly I know that I have it in me to do great things. But what great things? Just what?’ His son-in-law Ralph Rumney, who was also a friend, has remarked that as far as he is concerned, Laurence was never given his due as an artist or as a man. Peggy loyally said that Laurence ‘was always bursting with ideas. He had so many that he never achieved them because he was always rushing on to others.’

Peggy and Laurence met again at a dinner party given by the Fleischmans. At the time he had a minor reputation as an artist and writer, but a much greater one as a man-about-town and roué. He was very popular with women, and when Peggy met him again in Paris he was in the middle of an affair with Helen Fleischman. It was an affair which her husband Leon had encouraged, since the thought of such a thing excited him, and Helen warned Laurence not to flirt with Peggy – for fear of offending Leon. She may, however, also have realised that Laurence found Peggy attractive. Peggy’s dark brown hair was parted at the centre and worn short and waved. Her light blue eyes had a pensive, intelligent look. She was young, very pretty despite her nose, which had not yet coarsened, and had a beautiful, long-limbed body. She was charmingly naïve but eager to learn, and had a private income twice as big as Laurence’s mother’s.

For Peggy, not only was Laurence an artist and a good-looking and charming man, he embodied the cosmopolitan sophistication she admired. He knew Paris backwards. He knew about art, and he had friends in the world of modern art. He wasn’t a callow youth from a similar background to her own, and his world had little connection with Jewish New York. Here was the teacher she sought. They got on very well at dinner. Laurence owed no woman any loyalty at the time, and was well aware of the casual nature of his affair with Helen.

A few days later, Laurence rang the Plaza-Athénée, where Peggy was staying with her mother and Valerie, and asked her out for a walk. Laurence at thirty was still living with his sister and their parents in a large flat close to the Bois-de-Boulogne. Peggy dressed for the date in an outfit ‘trimmed with kolinsky fur’, the most expensive kind of mink, in order to advertise her material charms. She and Laurence walked up the Champs-Elysées to the Arc de Triomphe and then along the Seine. Dropping into an ordinary bistro for a drink in the course of what was a very long walk, Peggy ordered a porto flip – a cocktail which wouldn’t have raised an eyebrow at the Plaza but which hadn’t reached the Left Bank in 1921.

But Peggy had other things on her mind, and didn’t see Laurence as a teacher simply in terms of art. In another passage omitted from the 1960 version of her autobiography she remarks candidly:

At this time I was worried about my virginity. I was twenty-three and I found it burdensome. All my boyfriends were disposed to marry me, but they were so respectable they would not rape me. I had a collection of photographs of frescos I had seen at Pompeii. They depicted people making love in various positions, and of course I was very curious and wanted to try them all out myself. It soon occurred to me that I could make use of Laurence for this purpose.

Unaware of Peggy’s thoughts, but preparing to woo her, Laurence decided to leave the parental apartment and find himself an independent place. He told Peggy his plan, and she immediately suggested that she move in with him and share the rent. Balking at this – even in the progressive and permissive 1920s Peggy was going a bit too fast for his taste – he settled on a room in a hotel in the rue de Verneuil, between the Seine and the boulevard St Germain, and only a block south of the bohemian rue de Lille. Not wanting to lose the initiative, however, he soon visited Peggy in her room at the Plaza-Athénée, choosing a time when her mother, whose own room was nearby, was out with Valerie. Laurence took advantage of the situation and immediately made his move, only to be taken aback at the speed of Peggy’s acquiescence. But she stopped him anyway, saying that her mother might return at any moment and interrupt them. He suggested a tryst at his hotel sometime, but had his breath taken away when Peggy immediately fetched her hat. She later observed dryly that she was sure Laurence had not meant things to happen so quickly. Laurence was caught and cornered, and they both knew it. It would not be the last time, and it would be the cause of many violent rows in the future.

What could Laurence do but give in? He had, after all, made the first move. So she got her wish and lost her virginity, and in just the way she wanted. Peggy, typically, jumped in with both feet: ‘I think Laurence had a pretty tough time because I demanded everything I had seen depicted in the Pompeian frescos. I went home and dined with my mother and a friend gloating over my secret and wondering what they would think of it if they knew.’

Peggy had launched herself on a long sexual career, which she makes much of in her autobiography. She had lovers in such numbers that individually they were of no consequence. What is significant is how few relationships she had. Some of the bons mots associated with her sexual profligacy are well-known. When the conductor Thomas Schippers asked her, ‘How many husbands have you had, Mrs Guggenheim?’ she replied, ‘D’you mean my own, or other people’s?’ There is also the allegation, which Peggy denied in later life, that she had a thousand lovers. The number of abortions she may have had reaches seventeen, though other sources give seven. The true number is almost certainly three.

Peggy’s sexual voracity is well-documented, and there can be no doubt that for periods in her life she was extremely promiscuous. The reasons for this are complex. In part she was always looking for love, and she sought it through sex. It has been said that she had no interest in courting or even foreplay: she liked to go directly to the act of making love, and once it was over her detachment could be abrupt. In part she was both using sex as an expression of her own liberation, and in part she was conforming to the prevailing non-conformity. She was far from the only ‘liberated’ woman in artistic circles to behave in this way. In part, getting men (and occasionally women) into bed with her reassured her that she was not as ugly as she thought herself to be. In part, sex was a hedge against loneliness. It is significant that as she became established as an art collector of great standing in the middle decades of the twentieth century, she was increasingly known as ‘Mrs Guggenheim’. She approved of the name. But despite the fact that there were to be two real husbands, innumerable lovers, and one great love, the isolation symbolised by that name tells its own story.

Laurence and Peggy’s affair continued discreetly throughout the rest of 1921 and into 1922. As their romance blossomed, he introduced her to his world. Peggy, completely in his thrall, dubbed him ‘the king of Bohemia’, although he was that in her eyes only. Early on in their relationship, she speaks of him as playing a heroic central role in the move by the American artistic fraternity from the Rotonde to the Dôme. In This Must be the Place, the memoir of James Charters, the Liverpudlian ex-boxer who became the most famous expatriate cocktail provider in Paris in the 1920s, ‘Jimmie the Barman’, the story is rather different:

This came about because, back in those moralistic days, a ‘lady’ did not smoke in public. Neither did she appear on the street without a hat. But one Spring morning the manager of the Rotonde looked out on the terrasse, or sidewalk section, of his establishment to discover a young American girl sitting there quite hatless and smoking a cigarette with a jaunty air. Her hatlessness he might have overlooked, but her smoking – No! He immediately descended on her and explained that if she wished to smoke, she must move inside.

‘But why?’ she asked. ‘The sun is lovely. I am not causing any trouble. I prefer to stay here.’

Soon a crowd collected. The onlookers took sides. Several English and Americans loudly championed the girl. Finally the girl rose to her feet and said that if she could not smoke on the terrace she would leave. And leave she did, taking with her the entire Anglo-American colony!

But she didn’t move far. Across the street was the Dôme, which up to that time had been a small bistro for working men, housing on the inside one of those rough green boxes which the French flatteringly call a billiard table. Accompanied now by quite a crowd, the young lady asked the manager of the Dôme [a lucky man by the name of Cambon] if she might sit on the terrace without a hat and with a cigarette. He immediately consented and from that time the Dôme grew to international fame and became the symbol for all Montparnasse life.

Laurence threw big parties at his parents’ large apartment when his mother was away. Peggy has left us a recollection of one of them – her first. She sat on the lap of an unknown playwright, and self-consciously remembers the drunken ardour of Thelma Wood. (Wood was a native Kansan, at the time a pretty and slim twenty-one-year-old; she was a notorious lesbian and the then lover of Djuna Barnes, whose path was to cross Peggy’s often in the coming years.) The party provided other sideshows to titillate Peggy: two young men weeping together in one bathroom, two ‘giggling girls’ in another – all of which caused considerable distress to Laurence’s father, cast adrift among all this jeunesse dorée, and completely unable to cope with it.

Soon afterwards Peggy met two of Laurence’s ex-mistresses, Djuna Barnes, recently arrived in Europe as correspondent for McCall’s magazine (thanks in part to a subsidy of $100 for her fare from Leon Fleischman, who’d borrowed the money from Peggy), and Mary Reynolds, a woman of great integrity who would become the long-time mistress of Marcel Duchamp. Both were great beauties; both had attractive noses. Neither, however, was as well off as Peggy. Djuna in particular was strapped for cash and Peggy, at Helen Fleischman’s suggestion, gave her some lingerie. This caused a row. According to Peggy, Djuna was affronted at the gift, since the underwear, from Peggy’s own wardrobe, was not even her second-best and was darned; she goes on to describe an odd scene in which she bursts in on Djuna, who was seated at her typewriter, dressed in the offending garments. In a letter to Peggy much later, in 1979, Djuna explained that the insult was in Peggy’s mind: ‘if you are “correcting” the re-issue of your book, you might remove the remark that I was “embarrassed” by being “caught” wearing the handsome (mended) Italian silk undershirt – I was not annoyed at that, (or I should not have worn it). I was annoyed, and startled, that someone had come into my room, unannounced and without knocking.’

Peggy, who clearly felt guilty about her meanness at the time, made amends by the gift of a hat and cape, and the incident did nothing to damage what turned out to be a lifelong relationship, though never quite a true friendship, since Djuna was forever financially needy, and Peggy supported her for most of her life. This aspect of their association was not helped by the fact that Djuna considered herself in every way an infinitely superior being to Peggy.

Meanwhile the affair with Laurence continued apace. In order to give themselves greater freedom of movement, Peggy persuaded her mother to take a trip to Rome; although Valerie was left behind as chaperone, she was easier to outwit than Florette. Matters came to a head soon afterwards, when Laurence took Peggy to the top of the Eiffel Tower – did she tell him that her father was responsible for the elevators? – and proposed to her. Quite how ardent the proposal was, we don’t know; but she accepted him immediately, and he promptly got cold feet.

Laurence continued to dither and Peggy continued to hang on. As soon as she got wind of the engagement, Laurence’s mother, disapproving of a liaison with a Jew, however rich, packed her son off to Rouen to think things over, sending Mary Reynolds with him (and paying her fare) in the hope that old embers might be rekindled, or at least that Mary might talk some sense into her former beau. Her plan misfired: Laurence and Mary did little but row, and Laurence sent Peggy a telegram telling her he still wanted to marry her after all.

Peggy pressed home the advantage by letting her mother in Rome know that she was engaged. This brought Florette back to Paris in a panic. She disapproved of Peggy’s ‘marrying out’, and in any case knew nothing of Laurence’s credentials. He wasn’t rich, that was for sure. Laurence was, however, able to come up with the names of one or two people who would speak on his behalf: one of them was King George II of Greece, whom Laurence, with his wide circle of acquaintances, had once met at St Moritz. Luckily, Florette didn’t follow up any of the references, but she mobilised Peggy’s relatives and friends to dissuade her.

Despite this the couple went ahead with their plans, Peggy taking care that the lawyer they engaged ensured that her money should remain in her control, and the banns were posted. Laurence promptly started to dither again, but this only strengthened Peggy’s resolve. Then, when it looked as if he might be going off to Capri with his sister, and Peggy would be bound to return to New York with Florette, he turned up at the Plaza-Athénée, where Peggy was sitting in the unlikely company of her mother and his, and asked her to marry him ‘the next day’.