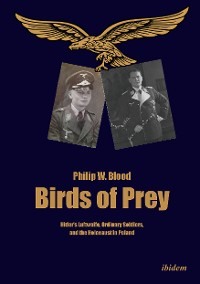

Birds of Prey

Engaging with microhistory

This book was conceived at a particularly lively period of historical discourse and debate. The contemporary interpretation of Hitler’s war had begun to take shape in the 1980s. For example, Omer Bartov had noted, ‘The collaboration of the army with the Nazis and its role as the instrument which enabled Hitler to implement his policies, were most evident during the war against Russia.’11 Since German rearmament in the 1950s, the story of the Wehrmacht’s complicity in Nazi crimes had been resisted. Bartov’s book was an uncomfortable reminder of the reality of the war, just as the Cold War was about to end. By the 1990s the literature was directly questioning the mass mobilisation of manpower as directed towards the Holocaust. Christopher Browning had observed, ‘… the German attack on the Jews of Poland was not a gradual or incremental program stretched over a long period of time, but a veritable blitzkrieg, a massive offensive requiring the mobilization of large numbers of shock troops.’12 In Germany, the Wehrmachtausstellung opened in Hamburg, an exhibition that explained the Wehrmacht’s participation in Nazi crimes. A controversy over the content forced the exhibition to close and one of its organisers forced to step aside.13 Hannes Heer, having stepped down from the exhibition, published his interpretation of the crimes of the Wehrmacht on the eastern front and included his essay on combating partisans.14 In 2000, I was able to discuss my ideas with Heer and soon recognised we shared similar conclusions about Bandenbekämpfung, as a means to bringing ordinary soldiers to Holocaust killing without an overbearing ideological hierarchy.

The Holocaust was also embroiled in lively debates in the 1990s. For a long time, Raul Hilberg’s three-volume study framed Holocaust scholarship.15 Then Daniel Goldhagen exploded the accusation that Germans had been willing executioners, ‘… this book endeavours to place the perpetrators at the centre of the study of the Holocaust and to explain their actions.’ He argued the ‘… institutions of killing detailed the perpetrators’ actions, chronicled their deeds, and highlighted their general voluntarism, enthusiasm, and cruelty in performing their assigned self-appointed tasks.’16 Since 1940, deportations had collected Jews from across occupied Europe concentrated them in Polish ghettos. In June 1941, the SS-Einsatzgruppen ranged across the rear areas in the wake of the German Army’s advance into Soviet Russia.17 In the Holocaust by Bullets, the SS killed or murdered upwards of two million Jews.18 From mid-June 1942 the destruction of the ghettos set off another wave of deportations to killing centres, but this also sparked outbursts of Jewish resistance.19 By December 1942, Hitler’s war against the Jews had escalated into a three-part process involving deportations, killing centres, and mass deaths. The evidence collected for Birds of Prey confirmed that Luftwaffe troops were assigned to this process.

There were other challenges to collecting evidence. During the period 1941–44, Białowieźa forest came within Bezirk Bialystok, a Nazi occupation zone administered from East Prussia. Göring’s ambition was to bind East Prussia and Ukraine in a common frontier with Bezirk Bialystok—a land bridge between the two. This represented a racialized colonial frontier of fewere than 3 million Germans under Erich Koch, ruling over 35 million people (Ukrainians, Belarussians, Poles, and others). This particular region was under-researched, but for Christian Gerlach’s published doctoral thesis, which is cited in the narrative of this book.20 In Hitler’s Empire (2008), Mark Mazower referred only to Ukraine and noted that the SS had difficulties working with Koch, who became virtually untouchable after turning East Prussia into a pro-Nazi state.21 Koch could rely on both Hitler and Göring to back him during internal squabbles. The greater challenge to my research, however, was the glaring absence of evidence about Bezirk Bialystok in the archives.

Before applying Historical GIS (explained in chapter 1) to the research, several attempts were made to construct a more traditional historical structure for the manuscript. The classic study of a German town, under Nazi rule, was also considered a viable option because it was compact.22 There were parallels of cultures, anthropology and localism. Allen claimed his ‘microcosm studies’ were unrepresentative of the Nazi regime but encouraged detailed analysis, which initially made it an important option. The closely relevant study was Christopher Browning’s Ordinary Men (1992), the study of a police battalion in the Holocaust.23 The book examined records from Federal German investigations, compiled from perpetrator interrogations and testimonials conducted more than twenty-five years after the war. Browning concluded the Nazis had unleashed a ‘blitzkrieg’ against the Jews, and ordinary men had carried out the killings. There were parallels of scale between police and Luftwaffe battalions, but whereas Browning could construct a case based on postwar testimonies, this was not available for a study of the Luftwaffe. Memory-based evidence has limitations, even with Federal investigations, but the greater problem was the lingering myth of the ‘clean Wehrmacht’, which included the Luftwaffe. Overcoming the myth was challenging.

The impact of the Historical GIS research is explained in detail in ‘Reading Maps Like German Soldiers’ (chapter 1), but it should be recognised that it was central to redirecting the research. The final microhistory version adapted for the book as a consequence of working with the GIS maps. Several scholars were identified as endorsing the benefits of microhistory long before its actual appearance as a specific methodology. Eric Hobsbawm defined ‘grassroots history, history from below or history of the common people’. This is referred to as Alltagsgeschichte by German historians or everyday history.24 Hosbawm’s Marxian interpretation of ‘history of the common people’ was a dialectic that might be applied to the history of the common soldier. In comparison to Hosbawm’s observations about the traditions of oral history to the working class, similar characteristics exist for the common soldier. The lowly soldier’s social structure was confined to a traditional militarised hierarchy, with orders from above forcing ‘confrontation or co-existence’ with officers and NCOs. To construct an interpretation of how the soldiery responded to Nazi dogma required a deeper understanding of the Wehrmacht beyond the battles and operations. This also involved an understanding of the cultural transformation from conventional combat to occupation, and vice versa, with some comprehension of how the soldiery survived the war beyond the usual glib interpretations of luck. Hosbawm’s ideas greatly suited the social history of the soldiery.

A wholly unexpected outcome from my research was the prominence of the German hunt in shaping events (on this see chapter 2). This coincided with a new study that advised: ‘military history, … is a promising candidate for … microhistory’, and later added ‘military history gives ample scope for the microhistorian.’25 This was a significant theoretical development, but there were no examples to support the claim. The application of microhistory in Holocaust history also illuminated how the intimate scrutiny of Nazi perpetrators could transcend everyday life and everyday killing.26 These microhistories seemed to fit the environmental and forestry conditions of Białowieźa. The conditions had formed a peculiar impression of Białowieźa on the Germans, which they dubbed Urwald Bialowies. The Mammal Institute (Białowieźa) had published several important publications, which have discussed life during the occupation.27 Historically, forestry and hunting have been dominant themes in German literature for centuries, while foreign observers have been rather whimsical about the national fixation with ‘gloomy forests’.28 The weight of forestry literature threatened to overwhelm the research for this book, but it should be recognised that the power of Białowieźa dominated the collective mindset of the Germans.29 Throughout the Luftwaffe war diaries, there were constant references to Urwald Bialowies, in almost an arena like context. Birds of Prey has attempted to reproduce that notion of an arena of killing, where the Germans imagined themselves as warriors of antiquity.

The hunting culture was politicised by Göring to serve as a code of honour, which enforced the operational dogma in Białowieźa. Senior hunt officials perpetrated genocide from their first orders for extermination, which continued for the duration of the occupation. The hunter’s mission was set by Göring, but their actions at the local level were defined by individual responsibility. Beatrice Heuser recommended pursuing a deeper examination of hunting and war through Barbara Ehrenreich’s Blood Rites.30 This ground-breaking interpretation of war and hunting led to further reading. In particular, Simon Harrison touched on much darker kinds of hunting and human behaviour in war.31 Under the Nazis, the German hunt turned into an elitist social class. One observation with hindsight, these findings could have been contextualized within Michel Foucault’s theories of power and discipline. An etiquette of power shaped the mannerisms of the hunters, especially in their relations to non-hunters. The hunt’s social elitism, in the absence of monarchy and aristocracy, was directed towards the ritualisation of professionalism. Foucault’s doctors and patients could be almost role-reversed into the hunters and non-hunters. These threads formed an image of the naked display of power and professionalism, as depicted in the symbolism of the ‘hunter-warrior’ of Luftwaffe propaganda, labouring with genocide, in the wilderness arena of Białowieźa.32

The necessity to conduct field research in Białowieźa came from reading Riding The Retreat. In the preface, Holmes discussed his ‘growing reservations with what we might term ‘arrows on maps’ military history’ and being drawn to the ‘microterrain, that tiny detail of ground and vegetation that means so much to men in battle.’33 Holmes had previously engaged with the history of memory through the anecdotes of soldiers. Both Firing Line (1985) and Dusty Warriors (2006) were influenced by memory, the ‘other soldier’ in the case of the former, and himself in the latter as an observer on the ground. Holmes listened to veterans after the Falklands War in 1983, but in 2005 gave an impression of being on the ground in Iraqi. This transformation in Holmes’ writing, from listener to witness, was a lesson in historical change, that went largely unnoticed in reviews. A further contemporary impression of the dichotomies of military culture came from The Junior Officers’ Reading Club (2010). The author warned the readers that incidents in war are not recalled in exact detail. Hennessey reflected upon a war from yet another standpoint of soldiers’ responses during a hostile occupation. There are always doubts over the accuracy of reports and this was more prominent in wartime where accounts were often accepted at face value.34 There was one important study that could not be incorporated into the research findings. Thomas Kühne has written extensively and profoundly about soldiers within the context of identity and comradeship.35 Repeated attempts to incorporate his ideas failed due to fundamental gaps in the evidence. This was primarily due to the lack of personal evidence of the Luftwaffe soldiers, their shortened periods of service together, and the absence of any identifiable primary groups. In the final version, it was a collective of Hosbawm, Holmes, and Hennessey that pointed the way. The consistent reference to documentary evidence, but the caution of the unreliability of the bureaucracy underpinning that evidence was a constant finding in my research.

At the heart of this book is the German soldier—the Landser—the common soldier. The motivation behind this book was to understand who they were and how they were—in effect, a socio-cultural military history. Scholars and writers have reflected on who they were, why they fought for Hitler, and remained faithful to the bitter end; but the soldiers themselves have remained aloof, distant, and impenetrable. During the war, British military intelligence examined German fighting traits through PoW interrogations.36 US Army intelligence carried the subject into a wider analysis of military methods and innovation.37 After the war, civil-military relations scholars applied the interrogation reports to a ‘cohesion and disintegration’ thesis (1947). The authors identified a ‘primary group’ concept, which claimed to hold the fighting or combat troops together. The article also cited an interrogation report of a captured German NCO about the political opinions of his men—the reply was instructive:

When you ask such a question, I realise well that you have no idea of what makes a soldier fight. The soldiers lie in their holes and are happy if they live through the next day. If we think at all, it’s about the end of the war and then home.38

The timeless words of veterans’ attitudes from all armies. The article was widely read but with a limited appeal. A general perception of the German soldier remained of the well trained and highly disciplined soldier. Nazism had socialised the soldiery, which tightly bound the myths of the Landser during the war. In the postwar age, Germans grappled with the uncomfortable realities of the war. In the 1950s, foreign observations, like that of The Scourge of the Swastika, were directed at German society struggling to come to terms with the war and Nazism.39 From the 1980s, scholarship began to follow an empirical/analytical path, while popular genres embellished uncontested German veterans’ anecdotes which has continued to this day.40 In 1983, a study compared the respective performances of the German Army and US Army during the war.41 Omer Bartov published his research of Hitler’s soldiers, which adapted the ‘primary group’ thesis to German fighting formations.42 I was fortunate to be placed in London at a time when several leading scholars discussed their ideas about common soldiers and war. Following a London University German history seminar in May 1997, there was a discussion with Bartov. He believed there was a shortfall of records, in particular the German NCOs, thereby reducing the prospect for serious research.43 In a subsequent conversation with Joanna Bourke, following a lecture at the Wiener Library, she argued men killing in war, stripped of military identity and political ideology, could be the basis for a comparative study.44 Bourke’s impressions closely matched the acts of men in Białowieźa. However, the resort to public killings by the Germans represented extreme exemplary violence, which placed them in a separate category of Second World War belligerents.45 This basic idea for comparative analysis, however, never entirely disappeared.

The Landser, as portrayed in this book, emerged from scholarly engagements with German colleagues. Following discussions with the late Professor Wilhem Diest and Professor Stig Förster at conferences, a different path of research was set emphasizing the interactions of social class.46 An impression drawn from conversations with German veterans about their impressions of ‘combat’, ‘fire-fights’, and their sense of gratification from memories of being soldiers.47 In lengthy discussions with Professor Jochen Böhler, about German soldiers and their private letters, a richer impression of the Landser emerged. The culmination of the research identified the Luftwaffe soldiers as either reservists (mostly officers with civilian professions) or conscripts (mostly ORs from the lower classes). The only professional soldiers were the senior NCOs (no more than six), and none of their papers has survived. If these men were judged by their careers, they cut a cross-section of Third Reich society: farmhands, industrial workers, clerks, low-skilled technicians, tradesmen, trainees, beat police, and junior civil servants. They were a rag-tag collection of men mustered into small units. They did not represent the cream of the crop, and even Göring held little sway over manpower selection at the point of recruitment. They were poorly organized and were turned into cannon-fodder—even the non de plume ‘the poor bloody infantry’ did not describe their circumstances. They were not particularly well-armed; their first weapons were captured enemy booty from the Great War. Neither unit colours and class identity, nor duty and discipline, explained their motivations. They performed occupation security as dedicated perpetrators, but then gave a reasonable account of themselves as German soldiers in retreat. The fog of war.

Terminology

Some issues remained unresolved. There was evidence of Polish collaboration with the Germans, especially in hunting and as forest guides. Identifying those persons was impossible as Germans reports did not include names. The problem of confused languages was an added complication. German soldiers, usually clerks in headquarters, compiled combat reports that struggled with Polish and Russian names. In Białowieźa, the occupation bureaucracy cast transliterations of Polish and Russian. Today, the only impact of this chaos is to cause confusion to researchers. An example: the Polish town of Hajnówka was translated by the Germans as Gainovka during the Great War, and Hainowka under the Nazis. The Germans translated Białowieźa as Bialowies in both world wars. Pruzhany in Belarus was Pruzhany when it came under Poland before 1939, and Pruzana under German occupation. The GIS maps adopted the German and narrative took the present-day Belarus form. The other prominent towns including Narewka, Topiło, Czolo, and Popielewo, Suchopol, Bialy Lasek, and Kamieniec-Litewski have remained unchanged. The Germans referred to Narewka Mala in their reports and that name is used throughtout the manuscript in accordance with the German records. Many villages disappeared and their names later replicated far beyond the original site. Others cannot be identified on any maps and the reader has to accept that some villages are now lost from record and memory.

Since the war, there have been several changes in the political boundaries of the region adding further confusion to place names. To identify such places, the original name is adopted, but in brackets the present name and nation: for example, Nassawen, East Prussia (Lessistoje: Kaliningrad Oblast). Any faults in translations are of course mine. Time was also a critical factor in this book, because a certain level of real-time has been restored to events. The 24 hours clock regulated military life, with the Luftwaffe reports adopting that time system, but which time zone were they working towards—Berlin or Moscow? The Białowieźa occupation was a confusion of time. The Germans imposed curfews between dusk and dawn, which the partisans and Jews ignored. Luftwaffe patrols rarely began before dawn or continued after dusk; the partisans attacked when there were no patrols. The atmospherics of darkness and lightness is better reflected by am/pm, which is adopted throughout the book.

In principle, the citations for the archival sources follow the original text. However, certain sources the shortand, the notes and the unclear dates led me to anglicize dates and document pages to ensure clarity. For example, this German citation include document number in the diary and the anglicized date: “BArch, RL 31/2, document 3, Wehrmacht-kommandantur Bialowies Tgb.Nr 686/42, An des Lw.Sicherung-Batl. z.b.V. Bialowies, 29 July 1942.” Words can have legal implications for academic research in Germany. In 1992, Christopher Browning accepted the restrictions of Federal German laws for data protection on the use of names of individuals. Those laws are still in force at the time of writing, and I also agreed to abide by the strict code of privacy. In an article about Białowieźa from 2010, I adopted pseudonyms.48 Since then, several German books have placed the names of many individuals that were assigned to serve in Białowieźa in the public domain. My research database is more extensive than those books, and so I adopted a mix of anonymity and openness. For those persons not yet published in the public domain and in the interests of anonymity, I have adopted the first name with the first letter of the surname followed by two **—for example, Rudolf F**. The names of men already published remain in full—for example, Walter Frevert. The ranks of those from criminal organisations, such as the Nazi Party and the SS, have been kept to the original.

1 Christopher Hale, Hitler’s Foreign Executioners: Europe’s Dirty Secret (Stroud, 2011).

2 Jeff Rutherford & Adrian E. Wettstein, The German Army on the Eastern Front, (Barnsley, 2018), p. 41. They refer to Auftragstaktik as ‘Mission Command’, a commander ordered a mission, arranged forces and set the goal but then left it to a junior officer or NCO to complete the mission as they saw fit.

3 Michel Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: The Power and Production of History, (Boston, 1997), p. 1.

4 Blood, Hitler’s Bandit Hunters, passim.

5 NARA, RG165 721A, Seventh Army Interrogation Center APO 758, Final Interrogation Report, Historical Section of the OKL, Ref. No. SAIC/FIR/51, 3 October 1945.

6 Philip W. Blood, ‘Bandenbekämpfung, Nazi occupation security in Eastern Europe and Soviet Russia, 1942–45,’ PhD diss. (unpublished), Cranfield University, 2001.

7 Hans-Ulrich Rudel, Stuka Pilot, (Exeter, 1952), p. 36.

8 NARA, RG319, Winiza (sic) massacres, September–October 1952, 66 Counter-Intelligence Corps Detachment, 17 October 1952.

9 Autorenkollektiv, Bilanz des Zweiten Weltkrieges – Erkenntnisse und Verpflichtungen für die Zukunft, (Oldenburg, 1953).

10 H. Boog, Die deutsche Luftwaffenführung 1935–1945, (Stuttgart, 1982); W. Murray (1996), The Luftwaffe 1933–45: Strategy for Defeat, (Washington DC, 1996); J.S. Corum, The Luftwaffe: Creating the Operational Air War, 1918–1940, (Kansas, 1997).

11 Omer Bartov, The Eastern Front, 1941–45, German Troops and the Barbarisation of Warfare, (New York, 1986), p. 3.

12 Christopher Browning, Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland, (New York, 1998).

13 Hamburger Institut für Sozialforschung (Hg.), Vernichtungskrieg. Verbrechen der Wehrmacht 1941 bis 1944, (Hamburg, 1995). Hamburger Institut für Sozialforschung (Hg.), Verbrechen Der Wehrmacht: Dimensionen Des Vernichtungskrieges 1941–1944, (Hamburg, 2002).

14 Hannes Heer, Tote Zonen: Die Deutsche Wehrmacht An Der Ostfront, (Hamburg, 1999).

15 Raul Hilberg, The Destruction of the European Jews, (New York, 1985 revised).

16 Daniel Jonah Goldhagen, Hitler’s Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust, (New York, 1996).

17 Yitzak Arad, Shmuel Krakowski, Shmuel Spector, The Einsatzgruppen Report, (New York, 1989).

18 Father Patrick Desbois and Paul A. Shapiro, The Holocaust by Bullets: A Priest’s Journey to Uncover the Truth Behind the Murder of 1.5 million Jews, (New York, 2009).

19 Shmuel Krakowski, The War of the Doomed: Jewish Armed Resistance in Poland, 1942–1944, (London, 1984).

20 Christian Gerlach, Kalkulierte Morde: Die deutsche Wirtschafts- und Vernichtungspolitik in Weissrussland 1941 bis 1944, (Hamburg, 1999).

21 Mark Mazower, Hitler’s Empire: Nazi Rule in Occupied Europe, (London, 2008), pp. 153–4.

22 William Sheridan Allen, The Nazi Seizure of Power: The Experience of a Single German Town 1922–1945, (London, 1984).

23 Browning, Ordinary Men, passim.

24 Eric Hobsbawm, On History, (London, 1997), p. 201.

25 Sigurdur Gylfi Magnusson and István M. Szijártó, What is Microhistory? Theory and Practice, (London, 2013), p. 164 and p. 166.

26 Claire Zalc and Tal Buttmann (ed), Microhistories of the Holocaust, (New York, 2017).

27 Tomasz Samojlik, Conservation and Hunting: Białowieźa Forest in the Time of Kings, (Białowieźa, 2005), Bogumila Jedrzejewska and Jan M. Wójcik, Essays on Mammals of Białowieźa Forest, (Białowieźa, 2004); see also Jan Walencik, The Last Primeval Forest in Lowland Europe, (Białowieźa, 2010).